Tired of snow and bored out of my mind I was sitting in my living room, staring at my Facebook page.

I made a list of summer to-dos and posted them on my timeline. One idea was to cross Lake Michigan with my Zodiac. My coworkers and friends thought I was nuts. The weather on the lake can be very unpredictable and many things could go wrong, they said.

I was not convinced. I searched on the web for those who had crossed Lake Michigan and came across a story of a group of guys who kayaked across the lake. “Not a bad idea!” I thought. That was pretty bold coming from someone who had not seen or touched a kayak in years.

A month later I bought a Wilderness Systems Tempest 170 on Craigslist. I knew nothing about it other than it was 17 feet long and built for open water.

The weather was cold so I did a test run on a pond before going out on the open water. I didn’t have a kayak paddle so I used a canoe paddle instead.

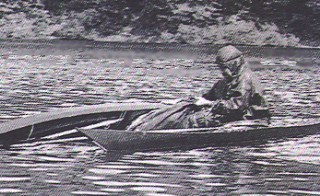

I’d never been in a sea kayak and wasn’t sure what to expect. I carried the boat to the pond, got in and launched. As I hit the water, I immediately rolled upside down into 40-degree water. That got a few giggles from my wife. I drained the kayak and gave it another go. This time I stayed afloat. I never realized how unstable these kayaks are compared to the wider, shorter, leisure counterparts.

The kayak sat for over 4 months before I took it out again. I’d been extremely busy at work and had entered a few local adventure races.

In the spring, I posted inquiries on several forums asking if anyone would be interested in kayaking the lake with me.

That sparked some interest, but no one was able to go come launch time.

By July I‘d purchased a spray skirt, paddle, night lights [i.e. running lights. Many of the author’s names for things have been left as he wrote them. Language can reflect a kayaker’s experience or lack thereof. Ed.], emergency signal kit, drybag, gloves and a life vest.

Uncertain that I would be able to do the Eskimo roll or a wet entry in open water, I decided to build an “anti-roll” set-up that would prevent the kayak from tipping over if I ran into rough weather. I purchased four buoys, two flag-pole holders and two aluminum windshield squeegees.

I’d hoped to launch in August but I wasn’t able to catch good weather when the time came. I set my sights on the week after Labor Day, Monday September 3. I had yet to purchase a device to track my progress, report my location and allow me to call for help in case of an emergency.

I found two such GPS-equipped devices. One was the DeLorme inReach. It transmits location and SOS and sends and receives text. It would also allow me to track my own location with a smart phone. The inReach uses Iridium satellites which was a big plus on my list but I couldn’t afford the hefty price tag and expensive service plan.

The second was the SPOT 2 GPS Messenger. It could broadcast my position and call for help but could not receive communication. It ran over the Globalstar network, which I’d read had some issues over the years. The cost of the device and the service subscription were within my budget.

I tested the SPOT 2 by sending locations and OK messages, not the 911 distress call, and it performed without failure. Having the SPOT 2 convinced my wife that it would be okay for me to do this trip solo.

With a week left before the trip I had to decide which direction I would paddle: Michigan to Wisconsin or the other way around? Both options had an equal number of advantages and disadvantages. Paddling from Michigan to Wisconsin would be easier as I would not have to deal with a ferry service when the time came to paddle.

I would also be paddling most of the time against the waves because the wind usually travels from west to east and I would see and anticipate what was coming but I’d have a longer crossing time. With approximately 80 miles between Milwaukee to Muskegon, I had no desire to make the trip any more difficult than it had to be so I decided to go from Wisconsin to Michigan. Instead of driving to Wisconsin I could take the Lake Express ferry. This service would get me over to Wisconsin in less than three hours saving time and money.

I picked up the remaining necessities: marine compass and bilge pump from Bill and Paul’s, a sports store in Grand Rapids, spare hiking compass, several flashlights, glow sticks, emergency horn, emergency strobe light, extra batteries and a shorty wetsuit.

Once my vacation began I checked the forecasts throughout each day to find a perfect window. The weather over the Labor Day weekend was not cooperating because of hurricane Isaac. The forecasts changed hourly, making my decision to set out very difficult.

On Monday, Labor Day, I finally saw a break in the weather forecast for Wednesday or Thursday. While making my reservation with the Lake Express ferry I was told I could bring a kayak only if atop my car. I called the only other ferry service the S.S. Badger. It sails between Ludington and Manitowoc and I could walk my kayak aboard without charge.

The Badger would leave from Ludington on Wednesday, September 5th at 9 A.M. and would arrive at Manitowoc four hours later. By paddling the 52-mile long Badgerroute my trip would be eight hours and nearly 30 miles shorter than paddling the Lake Express route.

On Tuesday I got the hardware for mounting the buoys and stopped at the local Dunham Sports Store to get a paddle. The paddle I had at the time was 240 cm, much too long. I had purchased it without knowing much about kayaking. I bought a nice aluminum paddle that was the right size and an excellent blade shape, which would allow me to get a better “grip” on the water.

The bright yellow blades would also make me more visible. At the grocery store I got a box of granola bars, two cans of peaches and two cans of pears. These cans did not require a can opener and would not take up too much room. The fruit would give me energy without filling me up too much. I bought one Powerade, a six pack of mini-V8 drinks and some bottled water. A can of Monster and a can of AMP, both caffinated energy drinks, would keep me awake and alert at night.

It didn’t take long to mount the stabilizers and get my gear “battle ready.” Attaching a leash to the paddle was a last minute idea. It would prevent me from losing my paddle in case it slipped out of my hands. By late afternoon, everything was ready to go. That evening I packed the car and sent an email to my friends with the link to the site where they could monitor my progress. I fell asleep around 11 P.M., watching the weather on my mobile phone.

I woke at 6 A.M. on Wednesday, grabbed the phone and refreshed the weather app. Two storms were passing over the lake but the evening was forecast to be clear with a chance of rain. Tired and unmotivated, I stayed in bed for another 30 minutes. In the back of my mind I had hoped that I could reschedule the trip, but I eventually jumped to my feet.

With a two-hour drive ahead, I was pressed for time. I left the house at 6:45 A.M. On the highway I set cruise control for 65 mph as I did not want to press my luck with the kayak strapped to the roof, but by 8 A.M. I was still a good hour away from the dock.

My speed went from a calm 65 to a frantic 85 mph. I finally arrived at 8:45 A.M. as the ferry was being loaded. I parked the car and crammed everything into my backpack and the storage compartments of the kayak. My first test of the trip was to see if I could lift the now extremely heavy kayak and carry it to the Badger.

The ship set off a little after 9 A.M. The weather was calm and there was no sign of the storm systems reported earlier that morning. To my surprise, the only waves I could see were caused by the wake of the ship.

The sky was clearing to the west and the chilly morning winds turned into a warm breeze. The Wisconsin shore finally appeared and the closer it was the more nervous I got.

At 1:00 P.M. the ferry reached the Manitowoc. I checked the weather one last time. There wasn’t a single cloud on radar as far west as Seattle, Washington. That cheered me up quite a bit.

I lifted my kayak to my shoulder and made my way to the small beach nearby. I was out of breath by the time I got to it.

I started to unpack my gear. I was not exactly sure that a lake crossing via kayak was legal. Honestly, I‘m still not.

I hurried to mount the stabilizers and the night lights to the kayak. The lights connected with suction cups. I was about to trust them with my life, so I taped them to the deck using Gorilla tape (the strongest tape I could find). I stuffed my food and drinks and emergency signaling kit behind the seat where I could easily reach them.

The backpack with my shoes, sweater and sweatpants went in the rear hatch. A small tool-kit, extra batteries and the Gorilla tape went in the hatch right behind the seat. I secured on deck the marine compass, glow sticks, emergency horn, extra paddle and the camera.

Slipping on the wetsuit, I decided to wear it half-up as the water and air temperature were somewhat warm. If it was going to cool off at night, I could simply slip the rest of the suit on. The life vest went on next. I turned on the SPOT 2 device and sent out an “OK” message.

I slipped on the spray skirt, jumped into the kayak and turned on the camera. After sealing off my dry bag containing the granola bars, gloves and hat, I placed it inside the cockpit, then attached the spray skirt. I pushed off at exactly 2:00 P.M. The water was calm and the weather was perfect when I left the port. I was very comfortable and it didn’t take long to get about five miles out.

I heard the horn of the Badger sound and 15 minutes later caught sight of it. I was about a quarter-mile south of its path. I couldn’t see any people on it, but I waved my paddle in the air to say hello anyway. The ship disappeared quickly past the horizon and the only thing I could make out was its smoke trail. I decided to paddle in that direction.

Before leaving on this trip, my wife told me that if she did not receive an “OK” message every two hours, she would call the Coast Guard to come for me. I made a point to send out an OK message approximately every hour.

The buoys were doing an excellent job of keeping the boat stable. Even though they caused some drag, they prevented lateral roll and allowed me to concentrate on paddling instead of balancing.

The sun was beginning to set. There was a fairly strong breeze blowing out of the southeast and the water was getting a bit choppy. The Wisconsin shore was no longer visible and I started to feel a little freaked out. Taking a short break, I chowed down a can of peaches and a granola bar. There were no more Powerades left, so I had some bottled water.

My shoulders were sore, so I took an ibuprofen. After sending out another “OK” message, I scanned the horizon and pushed on. I was about 20 miles out.

I kept my course southeast. Not long after the sun set I reached out front with my paddle and turned on the red and green bow light. It was a tricky feat as the button was nearly flush with the housing.

I then reached back and fought the stern light. It kept giving in under the weight of the paddle as I struggled to depress the ON button. I was praying the taped suction cup would not give out. The sun set so I activated a few glow sticks and secured them with the bungees in front of me.

That proved to be a dumb idea as I could not see anything but their glow. I moved them behind me, hanging off each side of the boat. I kept one red stick, covered up with the GPS device, to light up the marine compass. It was pitch black and eerily quiet.

Waves occasionally broke over the kayak and startled me. One wave broke right next to me with a loud hissing sound that made me jump. I hit my sunglasses with the paddle—they were secured by a bungee in front of me but they went flying overboard and sank. To calm myself I sent out another “OK” message. After a granola bar and a few gulps of Monster I kept going.

I saw a small white light on the horizon to the northwest. It glowed brighter and larger with every minute.

It was slowly getting closer. I expected it would pass behind me if it continued on its path. The light split into the bow and the stern lights of what appeared to be a large cargo ship.

At approximately 10:45 P.M. the ship was at my seven o’clock, approximately a quarter-mile away and traveling southwest. It was comforting to know that I’d be able to spot vessels a long way out if I paid attention.

A green flare shot up about 200 meters in front of me, hung in the air for a few seconds then disappeared. I’d never seen a green flare before and I wasn’t sure what to make of it.

An emergency flare would be red in color. White flare would signify a man overboard, or someone trying to illuminate the area. Green flare? [Two Coast Guart stations in the area had no record of reports of a green flare and knew of no special meaning of the color. Alex cited a website (truflares.us) that listed green flares as signals meaning “OK.” Ed.]

After a moment of sitting there I decided to paddle to where the flare went up. If this was an emergency I would be able to help out. There were no lights and I could not hear anything. If a boat was out there, dead in the water with no lights, I could run straight into it.

I turned on one of my flashlights, stuck it under the bungees and pointed it forward. I would paddle and then stop to listen. 15 minutes passed and I couldn’t hear or see anything. I sent out a “custom” message through my GPS device. Although it would state “Taking a break” it would note the location for the Coast Guard in case someone was in fact in trouble.

Still wary, I stopped from time to time to look and listen.

After returning home from the trip I learned my wife had called the Coast Guard and asked them to track me. My guess is the Coast Guard contacted the passing cargo ship and asked them to check if I was OK. The cargo ship fired off a green flare, which apparently is used to signal either “Everything is OK” or “Is everything OK?” giving you a chance to respond with an emergency flare if you need help.

I saw a glow on the horizon directly ahead. It could only be Ludington. Being able to see something on the horizon lifted my spirits. I opened a can of pears and wolfed it down, chasing it with the remaining energy drink. A bit sore, I needed to stretch. I leaned back on the kayak and looked up at millions of stars. The Milky Way was directly above me. It could have been mere chance, but I knew I was halfway across the lake at that moment. The only sounds were from waves lapping against the hull.

Another hour passed and another glow appeared on the horizon north of Ludington. It was the moon slowly rising. As it rose higher into the sky the waves changed direction.

A breeze picked up from the southeast and waves were now coming at me from the north. It took me a few minutes to adjust the skeg and my paddling, which now required a bit more power on my right to keep me on course. I would adjust my bow to point east only to find it pointing southeast a few minutes later.

The struggle annoyed me. What bothered me even more was the breeze blowing in my face. I was not sure what the weather was doing, but I was beginning to get a bit suspicious. Southeast wind meant there was a storm system building to the west. I am no meteorologist, but I know the basics of weather development—I paid attention in middle school. I looked to the northwest.

A large storm system was building up right behind me with the bulk of it coming out of the north. The heavy clouds were lit up by the moon. I was nervous and paddled with more fervor than ever. If a storm was coming, open water was the last place I wanted to be.

The clouds seemed to move slightly northeast which meant that I needed to paddle more southeast to get out of their path. I raised the skeg and let the waves point my nose in the desired direction. I paddled nonstop, dispite my heavy arms and tired shoulders.

I noticed a flash of light at my eight o’clock. Initially I thought it was moonlight reflecting off the water splashing from my paddle. I ignored it at first, then I saw it again and again. It was lightning, high up in the clouds I’d been tracking. Paddling against wind was bad enough, but I now had to deal with a storm system that would cause large waves.

There was lightning and the highest object in a 10-mile radius was my head and my trusty aluminum paddle. I kept an eye on the clouds as I pushed southeast. By the time the moon was directly overhead I noticed a couple of faint red lights on the horizon.

This meant that the shore might be only about 15 miles away. I calculated that at three miles an hour it would take me five more hours to hit land. I stopped for a break while I enjoyed the last can of fruit. My shoulders were killing me, so I took another ibuprofen and gulped down two surprisingly refreshing V8s. Recharged and freshly motivated, I continued.

The lights on the horizon multiplied and I had about eight of them in my sight. It was difficult to determine which light would lead me to the harbor. Picking the wrong direction would add extra miles that I was not willing to paddle. I began to sing to stop myself from complaining.

A new storm system appeared behind me and rapidly came closer. More lightning kept me alert and I pushed harder. Luckily it soon passed to the northeast. The horizon was becoming lighter and finally the sun appeared, peeking out through the clouds.

I could no longer see any lights, but I could see the faint outline of the shore. I estimated to be about 10 miles out at that point. The sun rose in early September at approximately 7 A.M., which meant I had another three hours or so left in my trip. Those three hours proved to be the longest of my life.

I ate my last granola bar and drank the last of my water. I was feeling extremely tired. Another rapidly approaching storm system was the only thing keeping me going. I was careless at that point and I did not look back. I wanted to reach shore, get out of the boat and take a nap.

It felt like no matter how much I paddled, I was not getting any closer. As the sun rose, I fixed my sights on some sand dunes directly ahead. They were the only landmark I could clearly make out. I started to count my stokes. Each minute felt like an eternity. I noticed a couple of sailboats cruising up and down the coast. I was so close!

A few miles out from shore, I began to feel like my kayak was slowing down. Indeed, I was no longer making much progress. I was not sure if it was the offshore wind or if I was fighting a current. I tried to muscle through it but the kayak came to a crawl. I turned around and saw the left stabilizer had given way.

It had collapsed backward, dragging and causing the kayak to turn left. I had to break it off. I reached out and grabbed the stabilizer and it popped right off. Immediately the boat became unstable. I carefully tucked the broken stabilizer under my bow bungees. I tried paddling forward, but I was going nowhere. The right stabilizer, now unbalanced, dragged and turned the boat to the right. I had to take it off too.

I were extremely uncomfortable doing this. If I was to accidentally roll over and go in the water, it would be extremely difficult to get back aboard—not impossible, but not something I wanted to try after being up for over 24 hours straight. Balancing, I grabbed the stabilizer. I pulled but it would not bend. I then leaned back and pulled the stabilizer straight up. It buckled and collapsed, but didn’t break off. The boat was wobbling as I got used to balancing it. I rocked the stabilizer back and forth until it broke off, then tucked it under the bungees with the other stabilizer.

I paddled toward the sand dunes. After an hour of nerve-wracking paddling I was frustrated and decided to signal to see if one of the sailboats would help. I made three short blasts with the

emergency horn.

There was no sign of response. I tried again, with longer blasts. No response. I paddled for another five minutes or so and tried again. No response. I continued this for another 30 minutes until the horn was out of pressure. By this time the sailboats were only about a quarter-mile away, but there were no signs of either boat responding. I was not making any progress and if there was a rip current, then fighting it head on wouldn’t work.

The only way to defeat this was to paddle diagonally to shore. I would travel a longer distance but I’d get to where I needed to go. I headed northeast toward a large lagoon. It was much farther away than the sand dunes but I found myself making better progress in this direction. I was exhausted but I had to keep moving.

There was a fishing boat heading in my direction. As it came closer I pulled the skirt back and pulled a flare from my emergency signaling kit. I sat there for a minute to make up my mind, then removed the protective cap and yanked the cord. The flare shot up a hundred feet in the air with a loud bang. It glowed for 5 to 10 seconds and then disappeared as I waited for a response. None came.

I was shocked. The lack of response ticked me off. This anger gave me energy I didn‘t think I had left. The boat was gliding well through the water. I heard a distant blast of a horn directly ahead of me. It was the Badger sailing for its morning run. It was 9 A.M.

Shortly after I saw the Badger coming out of the channel, I noticed the silhouette of the small lighthouse indicating the pier. Incredibly I was going in the correct direction all along. I was hesitant to enter the channel as I was not sure where the Badgernormally docked. I decided to make landfall on the small beach near the pier.

I made the last turn around the pier, took a few more strokes and hit the sand. It was exactly 10 A.M. when I reached my goal. I’d paddled 62.26 miles in 20 hours.

I tumbled out the kayak and stood up but nearly fell over. I dropped to my knees in a foot of chilly lake water. I could feel every aching muscle, yet I felt completely relaxed. I finally got out of the water and lay down in the sand. After a few minutes of rest I got up, pulled out the first-aid kit and took my last ibuprofen. I turned off the SPOT 2 GPS messenger.

The rear hatch took on some water during the trip, leaving my spare clothes, including my shoes, soaked. I found my cell phone and keys and I decided to hike to the car barefoot. I tossed the lifejacket, sprayskirt and wetsuit in the kayak.

A group of Coast Guardsmen were busy removing the “No Swimming” buoys from the beach in preparation for the winter. I asked them to keep an eye on my stuff for a few minutes. I walked to my car and drove back to the beach in a daze. I had no energy to carry my kayak nearly 300 feet across the sand so I drove onto the beach and pulled alongside my kayak. I was in no shape to lift the kayak—I needed a break before attempting that. I sat down in the car, closed my eyes and immediately fell asleep. The engine was still running.

I awoke to a tapping on my window. One of the Coast Guards was saying “You probably should not be sitting here…” but stopped when he saw my face. “Hey, you OK?” he said. The only thing I remember saying was “I’m sorry. I normally don’t pull these sorts of stunts.” The guy offered to help and called over a few of his buddies. We tossed the kayak up on the rack strapped it and I drove off the beach. The first restaurant I came across was a McDonalds. I ordered a chicken sandwich with some fries and a coke.

I’d felt I was in no shape to drive but the food gave me a sudden rush of energy and I decided to drive myself home. I’d been having trouble with my cell phone and hadn’t been able to call my wife so I turned on the GPS device and sent an “OK” signal that would show I was on land.

When I pulled into my driveway, I stumbled out of the car and walked into the house. After a long, hot shower, I konked out for about an hour on the couch until my dad, wife and best friend popped in to congratulate me on completing my adventure and of course, for surviving.

Alex Tsaturov lives in Ada, MI, and works in information technology incident management. You can find videos of his Lake Michigan crossing and other pursuits at www.youtube.com/user/rxakt2000.

Lessons Learned

This is an unusual story for Sea Kayaker. Alex submitted it at the urging of some of his friends and described it as a tale of “extreme adventure.” After reading his account I was left with the impression that it was as much an adventure as it was an accident that didn’t happen.

Although he was successful in making his crossing, his story had to be presented as a safety article pointing out the mistakes that could have led to an accident. Alex graciously consented to this approach.

The purpose of our safety articles is to offer useful lessons to sea kayakers. The benefit any of us can derive from the Lessons Learned is linked to the degree to which we can identify with and sympathize with those kayakers whose stories are told here.

(Aras Kriauciunas conveys this in his article on risk perception in this issue.) I’d venture that few of our regular readers will identify with Alex any more than Alex thought of himself as a kayaker. There may still be something of value in his story.

Sea kayaking vs. athletic events

Alex had competed in local adventure races, events that combine trekking, bicycling and canoeing. Hosted by Grand Rapids Area Adventure Racing (GRAAR), the entry-level races last from four to six hours. The races are, according to the GRAAR website: “designed to test an athlete’s physical and mental endurance as well as skills in a number of disciplines.

While physical fitness plays an important role in adventure racing, your mental fitness or ability to keep pushing yourself, is just as important.” I didn’t find much emphasis on skills on the website: “The only prior training you might need to undertake is in navigation skills with a map and compass.”

For the paddling stage, canoes, paddles and PFDs are provided. Competitors who don’t have access to paddling gear for training can still enter the races. (There is an open division for advanced racers; they are allowed to use their own paddling equipment.)

Alex’s racing and his training for the adventure racing would have improved his strength and endurance for a long crossing, but wouldn’t have added to his skills as an open-water kayaker.

The kayaking stage of that race took place on the exposed coast of the Bay of Fundy and was intended as a test of endurance. A sudden and violent squall turned it into a test of sea-kayaking skills. As I mentioned in the review: “Had the incident been written up as an article for Sea Kayaker, the Lessons Learned section would have little more than a review of basic safety practices.”

In another racing-related kayaking fatality (“A Race against Time” SK April 2008), two adventure racers in Sweden set out on a March training run. The kayaks they used were designed for fitness paddling and poorly suited for rough water and self-rescue.

They had long cockpits to allow for leg drive and were built without bulkheaded flotation compartments. After paddling out of a lee and into rough water, one of the pair capsized.

The lack of proper equipment and training in rescue techniques led to his death. In both of the incidents cited here, the capsized kayakers made efforts at self-rescue while other kayakers stood by watching, failing to employ assisted rescue techniques simply because they were unaware that such techniques existed.

Athletic endeavors have specific goals and athletes reach them by taking a single-minded focus. Bailouts and back-up plans aren’t part of the mindset, and may even prevent athletes from giving their best performance. With sea kayaking, it’s best to have options.

Long, open water crossings appeal to some because they require commitment. Retreat is an option early on, but when the hardest work has to be done you may have only two options: reaching the goal or calling for rescue.

When kayaking is one of several disciplines of adventure racing and approached as an athletic endeavor, participants can miss the wealth of knowledge accumulated by the sea-kayaking community.

Maritime pursuits have historically been steeped in tradition and with good reason. There’s a lot to learn to be safe on the water and to manage a boat. Training assures that the newcomers safely learn about the risks and acquire the skills to deal with them.

Physical limits

Paul McMullen told us about his attempt to kayak across Lake Michigan. Paul had served as a rescue swimmer with the Coast Guard and he was a world-class track athlete. He rented a kayak (one faster than the one he owned) for the 83-mile east-to-west crossing from Grand Haven to Milwaukee, a route very close to the Muskegon to Milwaukee route Alex had considered.

He set out at 5:00 P.M. on September 7, 2006—the Thursday after Labor Day, a date and a time similar to that of Alex’s crossing. The weather was fair when he set out but in the early hours of Friday morning, the wind picked up. The waves built to three to five feet and the headwinds dropped his forward progress to just two miles per hour.

Seasick, taking on water and still 30 miles shy of his goal, he activated his EPRIB. A freighter traveling north found Paul by chance, not because of the EPRIB, and rescued him.

With Paul we have another very fit athlete, but strength plays only a small part in making a long crossing. There are limits to the kind of power even the fittest person can generate.

If you look at the resistance figures that accompany Sea Kayaker’s reviews of kayaks, you’ll see resistance measured in pounds at particular speeds. The Arluck III that Paul was paddling generates slightly less than three pounds of resistance at 3 ½ knots—Paul’s average speed over the 52 miles he had paddled. The resistance figures are based on towing tank data—straight-line travel on flat water and in still air—but they’re good ballpark figures for paddling in calm conditions.

The three pounds of resistance indicates that only three pounds of propulsive force are required to maintain that particular speed. The results of Sea Kayaker’s early research into resistance concluded, “A fit paddler can maintain a cruising speed at three pounds of drag. Only a few can work against five pounds of drag for long distances.” Taken from the paddler’s side, that means that even exceptional paddlers can generate just five pounds of propulsive force during a long passage. That’s one sixth of the thrust generated by a small, electric trolling motor.

A moderate headwind can nearly double the effort of maintaining a cruising pace. A simple formula for converting wind speed into pressure is: The square of the velocity in miles per hour times 0.0027 equals the pressure in pounds per square foot. If we assume the frontal area of a kayaker is 3 square feet, paddling into a 15 mph headwind at 3.5 knots (4 mph) is meeting 2.77 pounds of wind resistance.

Add that to the 3 pounds of resistance in the water and you’re at 4.77 pounds of drag, very close to the 5 pounds of propulsive force a strong paddler can generate. Keep in mind that increases in resistance are a function of the square of increases in speed. As paddling conditions deteriorate, our limits come up very quickly.

Athletic events are about gauging the strength and ability of one person against another. In the coastal environment, we can fare well if the forces we confront are on a human scale. The power of natural forces can quickly and easily exceed that scale.

Testing mental endurance

The GRAAR website notes: “While physical fitness plays an important role in adventure racing, your mental fitness, or ability to keep pushing yourself, is just as important.”

The ability to persevere is important in sea kayaking, but it most often comes into play when we’ve overreached our abilities. It’s natural to wonder what we might be capable of and athletics provide an opportunity to test that in a structured environment.

Within that context, it’s appropriate to “leave it all on the race course.” If you’ve ever had to resort to your mental fitness to extend your physical limits on open water or along a hostile coast, it’s quite likely you’ve made some serious errors in judgment.

In racing you push your limits voluntarily. You don’t have to continue. Any race that’s a good test of endurance should have a number of entrants winding up in the race results’ DNF (did not finish) column and a safe way to withdraw from the race. Open water crossing without an escort leaves you with no good options for withdrawing.

Equipment and knowledge

Alex found his kayak online through Craigslist. Trying to keep within a tight budget, he opted not to buy a new kayak from Bill and Paul’s Sporthaus in Grand Rapids, the nearest retail store specializing in kayaking gear. Alex purchased a Wilderness Systems Tempest 170 from a seller who’d received the kayak in trade and knew nothing about it.

Alex could have done much worse with his luck online. The Tempest 170 was the Sea Kayaker Readers Choice for Best Day/Weekend Touring kayak. It is designed for the “entry-level enthusiast up to the advanced paddler looking for a seaworthy rough-conditions boat.” I paddled the Tempest 170 Pro (the composite version of the rotomolded kayak Alex purchased) for my review in the Readers Choice article: “The cockpit offers solid connection with the boat through adjustable thigh braces snug hip bracing, solid foot braces and a back band that sits low where it doesn’t restrict the paddler’s range of motion.

The stability of the Tempest 170 is very good and the secondary stability is excellent, providing solid support for edging. The Tempest moves along nicely at a cruising pace: I could sustain 4.5 knots with ease. The fit and maneuverability of the Tempest 170 make it a pleasure to paddle.”

While Alex got a good deal on a good kayak, he got no advice on kayaking. I spoke to John Holmes, an employee at Bill and Paul’s who conducts many of the classes offered by the store.

The sales staff is trained to look for the “red flags” of customers purchasing equipment for activities that they may not be adequately prepared for. There were several sea kayaking classes offered in June and July of 2012. Had Alex purchased a kayak from Bill and Paul’s, there’s a good chance he would have been encouraged by the sales staff to take a class.

He did buy a compass and a pump from the Sporthaus, but that may not have been a purchase that raised a “red flag” about his lack of training. (Aras Kriauciunas’ article on risk perception also notes how we may base assumptions about paddling ability on the gear that people have or purchase.)

In the videos Alex took of himself during the crossing, it’s evident he is a self-taught paddler. There is no torso rotation powering his strokes. While Alex is powerfully built, the lack of training in the forward stroke must have contributed to his exhaustion as he neared the finish of his crossing.

Alex “drooled over the carbon fiber paddles at Bill and Paul’s but couldn’t justify spending 300 to 400 bucks.” The primary paddle he purchased came from a discount sports-store chain that offers inexpensive gear for recreational kayaking. Economy was a chief virtue of the aluminum/plastic paddle: “It cost me a whole $25. Can’t beat that!”

Alex was able to anticipate some problems. Employing a paddle leash was “a lesson I learned from the movie Cast Away,” Alex noted in our correspondence.

He remembered the scene when Tom Hank’s character lost his stand-in companion, a soccer ball named Wilson, to sea. “I thought that could happen to my paddle. A boogie board leash did a good job,” Alex said. In spite of his resourcefulness, naïve as it was, it would be impossible to anticipate everything that can crop up in a long crossing.

Training and sea trials

Alex mentioned that he likes to “learn everything on my own, and I end up being very good at whatever I do: ice hockey, motorcycles, tennis, free diving, etc. “I pick things up very quickly. Same with kayaking. It did not take me long to get a very good feel for it. I did watch quite a few videos online about wet reentry specifically.

I did get a chance to take this boat out to the lake in July or early August to practice reentry. In waves it was nearly impossible. I was able to get on the kayak and balance myself fine, but when trying to slide into the seat, the boat would roll. Without the water being very flat or having some sort of a float, it was extremely difficult to do. For those reasons I made my little

‘anti-roll’ set up.”

Like Alex, I enjoy learning on my own. There’s a measure of pride that comes with being self-taught, but it’s a slow way to learn, and you can develop some bad technical habits. An instructor can solve both of those problems. The word “educate” has a Latin root in “educere,” which means, “to lead out.” It implies two things: that there’s someone to do the leading and there’s something the student needs to be led out of. That something has to be ignorance. Not knowing what you don’t know makes it difficult and in some cases perilous to educate one’s self.

Advice

Alex wasn’t shy about his plans for the crossing when he was shopping for gear. “The reactions ranged from ‘You’re nuts!’ to no comments at all. The only suggestions I received were ‘Don’t do it,’ and ‘Get a boat to trail you.’ I said no to the latter suggestion, as to me that’s no sport.

No one, other than my friends and coworkers took me seriously. Those close to me know that if I set my sights on something, I achieve it.”

If people were not taking Alex seriously, it was because they couldn’t believe that he could successfully make the crossing with the skills, experience and even the equipment he possessed. But his intentions should have been taken quite seriously.

There was no reason to assume that he would not make the attempt and get well out from shore. It would be reasonable to assume that he would fail. There we should feel that we have a responsibility. “Don’t do it” and “Get a boat to trail you” were indeed very sound pieces of advice, but they were not effective.

Alex would make his decision to launch based on what he knew. The shortcomings in his preparation must have been quite obvious. He needed advice and an approach that would help him make a better-informed decision. Aras Kriauciunas touches on the process of swaying someone’s decision in his article in this issue.

Luck

Alex’s plan was shifted to a significantly shorter crossing by the refusal of the Lake Express ferry to take his kayak aboard. Paddling the route of the Badger saved him 20 miles.

Had he paddled his initial intended route and reached his point of exhaustion at 60 miles out (as he did on the Badger route), he would have had another 6 hours of paddling ahead of him. It’s very likely he would have had to use his SPOT 2 to send a distress call.

Alex carried a smart phone in a small dry bag. He had intended to use it to track his position by logging onto the website that mapped his SPOT 2 messenger’s “OK” transmissions. That worked for the few messages he sent in the first hour of his crossing, and he was able to get a rough idea of his speed. “It worked for the first two to three miles, then the connection degraded and then finally dropped.

When I left the Michigan shore on the Badger, the cell phone reception was great until approximately 10-15 miles into Lake Michigan. The Wisconsin side did not offer reception as good as that. I checked my phone maybe once or twice when I first paddled off from Manitowoc.

It worked for about the first hour. It did help me get an idea for how fast I was paddling at that time.” Fortunately, his wife would consent to let Alex make the crossing only if he had a satellite messenger that could send a distress call with a location. It would also provide updates on Alex’s progress once he was out of the coverage area of the land-based cell-phone system.

Alex was extremely lucky with the weather. He estimated the winds he faced during the crossing were about 10 miles per hour. The swell “just kind of rolled past,” and the wind waves were minimal.

The videos Alex took while under way show very mild conditions (Paul McMullen, paddling at the same time of year, encountered strong winds and 3- to 5-foot seas that frequently broke over his bow). The weather around Alex was unsettled. Thunderstorms can bring strong localized winds, but while Alex could see storm clouds, he did not have to contend with strong winds or rough seas. His outriggers were never put to a rigorous test, and one of them failed in mild conditions. He was able to break off the other, even though it was in an awkward position behind him.

The telescoping aluminum tubing of the squeegees would have almost certainly failed in rough water. Sea trials, a longstanding maritime tradition, are essential for learning what works and what doesn’t. If you don’t know by experience how your gear will hold up, or how you will hold up, you’re leaving your success to chance.

Looking back on the crossing, Alex said, “I am a huge risk taker and this is not the first time I have done something ‘stupid.’ This was very dumb and unsafe and it could have turned out differently.

Luck was a major factor. Anyone that knows anything about the Great Lakes knows that it can go from calm to ‘the perfect storm’ in a matter of minutes. My self-confidence got the better of me.” The experience of the crossing deepened his interest in kayaking and made it clear that he had a lot to learn. “I plan on going to a kayaking symposium that is held here in Michigan every summer. I am looking forward to the kayak clinics there and it will also be nice to get to know the kayaking community.”

Alex had taken up kayaking as an outsider and neither his web searches nor his encounters while shopping for gear brought him into our community where he could get the advice he needed.

As interest in adventure sports grows, there will be more people like Alex looking at kayaking as a way to challenge themselves. It would be a mistake to dismiss them for their bravado. Their naïveté is good reason to bring them into the fold as quickly as possible.

On Saturday, May 26, 2001 , 51-year-old Robert Beauvais participated in a sea-kayaking course for beginning paddlers—a six-hour class listed as Essential Skills I, run by a New England–based kayak school. The participants included four students and Carla, a British Canoe Union (BCU)–trained (Four Star) instructor. (Names of the staff and other students have been changed.)

On Saturday, May 26, 2001 , 51-year-old Robert Beauvais participated in a sea-kayaking course for beginning paddlers—a six-hour class listed as Essential Skills I, run by a New England–based kayak school. The participants included four students and Carla, a British Canoe Union (BCU)–trained (Four Star) instructor. (Names of the staff and other students have been changed.)

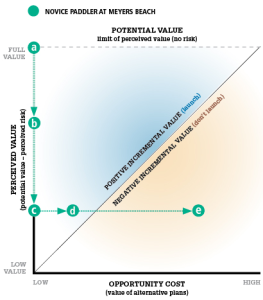

Before their respective launch discussions, both groups had the same potential value (returning from the trip) and the same perceived risk (weather forecast and skill levels), so the perceived value of launching was the same.

Before their respective launch discussions, both groups had the same potential value (returning from the trip) and the same perceived risk (weather forecast and skill levels), so the perceived value of launching was the same. In the example of the exchange between the experienced kayaker—Dave—and a novice, the conversation began with Dave’s effort to increase the novice’s existing perception of the risk (a to b) by discussing the dangers of falling into the water without a wetsuit.

In the example of the exchange between the experienced kayaker—Dave—and a novice, the conversation began with Dave’s effort to increase the novice’s existing perception of the risk (a to b) by discussing the dangers of falling into the water without a wetsuit. I just recently talked with a sea kayaker in Chicago who described an incident at Cape Fear in North Carolina. Garrett showed me some photographs of a rough sea and proudly explained how he had paddled right out through all the breakers and then sat marking time,

I just recently talked with a sea kayaker in Chicago who described an incident at Cape Fear in North Carolina. Garrett showed me some photographs of a rough sea and proudly explained how he had paddled right out through all the breakers and then sat marking time,  punching through each wave as it came.

punching through each wave as it came. cockpit, but every time a wave hit me, the paddle sheared around alongside the kayak like a pair of scissors closing and I capsized again.

cockpit, but every time a wave hit me, the paddle sheared around alongside the kayak like a pair of scissors closing and I capsized again. his time trying to climb back in, and that he had better swim for shore. His account made me think about self-rescues, about the dependence of many paddlers on equipment rather than on paddling skills and their reliance on self-rescue rather than group rescue. I see so many kayakers carrying an inflatable paddle float on their deck alongside a stirrup bilge pump. But I wonder how many of those paddlers have practiced in the kinds of waters they would capsize in? How many others, like Garrett, believe that self-rescue is not possible in rough water?

his time trying to climb back in, and that he had better swim for shore. His account made me think about self-rescues, about the dependence of many paddlers on equipment rather than on paddling skills and their reliance on self-rescue rather than group rescue. I see so many kayakers carrying an inflatable paddle float on their deck alongside a stirrup bilge pump. But I wonder how many of those paddlers have practiced in the kinds of waters they would capsize in? How many others, like Garrett, believe that self-rescue is not possible in rough water? While the paddle float was devised as a way to improvise an outrigger for self-rescue, its best use, in my opinion, is as an aid to a reentry and roll. Once the rudimentary principles of a roll are mastered, a reentry and roll with a paddle float can offer a reliable self-rescue, even though rolling without the float might still

While the paddle float was devised as a way to improvise an outrigger for self-rescue, its best use, in my opinion, is as an aid to a reentry and roll. Once the rudimentary principles of a roll are mastered, a reentry and roll with a paddle float can offer a reliable self-rescue, even though rolling without the float might still  be elusive.

be elusive. from the side as possible. Grip the near side of your cockpit with your other hand. Lie back in the water. Hold your breath and swing your feet into the cockpit between your hands. Still gripping both sides of the cockpit, wriggle yourself into your seat, and with your feet on the foot braces, grip firmly with your knees.

from the side as possible. Grip the near side of your cockpit with your other hand. Lie back in the water. Hold your breath and swing your feet into the cockpit between your hands. Still gripping both sides of the cockpit, wriggle yourself into your seat, and with your feet on the foot braces, grip firmly with your knees. grasp the paddle shaft with both hands and gently pull down against the buoyancy of the paddle float until your head reaches the surface and you can breathe and see what you are doing.

grasp the paddle shaft with both hands and gently pull down against the buoyancy of the paddle float until your head reaches the surface and you can breathe and see what you are doing. The paddle bridge requires the kayaks to be nearly parallel and just far enough apart to rotate the victim up between the kayaks.

The paddle bridge requires the kayaks to be nearly parallel and just far enough apart to rotate the victim up between the kayaks. It’s also better for the rescuer’s kayak to be parallel to that of the victim to prevent a collision, and allow the rescuer to grasp the bow or stern of the victim’s kayak. By holding the bow and bridging his or her paddle across both kayaks, the rescuer’s bow is automatically at or near the victim’s hand. Another advantage is that the rescuer can keep the bow from swinging out of reach during the rescue by moving the lower body.

It’s also better for the rescuer’s kayak to be parallel to that of the victim to prevent a collision, and allow the rescuer to grasp the bow or stern of the victim’s kayak. By holding the bow and bridging his or her paddle across both kayaks, the rescuer’s bow is automatically at or near the victim’s hand. Another advantage is that the rescuer can keep the bow from swinging out of reach during the rescue by moving the lower body. There are also Eskimo rescues for extreme situations, where a kayaker might get out of the kayak and have to be carried piggyback on someone’s afterdeck. This is extremely dangerous in cold water. There was a poignant story told by Dr. Alfred Bertelsen, a medical researcher in Greenland around 1900. Three brothers were out hunting in kayaks when one of them capsized. He exited his kayak after failing to roll up. His brothers managed to get him up between them, but he froze to death in their arms.

There are also Eskimo rescues for extreme situations, where a kayaker might get out of the kayak and have to be carried piggyback on someone’s afterdeck. This is extremely dangerous in cold water. There was a poignant story told by Dr. Alfred Bertelsen, a medical researcher in Greenland around 1900. Three brothers were out hunting in kayaks when one of them capsized. He exited his kayak after failing to roll up. His brothers managed to get him up between them, but he froze to death in their arms.