THE DECISION TO GO

I had been thinking about paddling in Alaska for a long time. Many kayakers I know have paddled there, most of them in organized groups, and almost all of them in Prince William Sound. My friend and fellow kayaker, Albert, instantly accepted the idea of paddling in Alaska, but proposed a different Alaskan destination, the Kenai Fjords.

We both are committed kayakers. I’d been kayaking for six years year-round, along the Mediterranean coasts of Tel Aviv and Herzlia. I made a few kayak trips in Greece, visited Wales during summer and winter for the intense BCU Five-star training, and joined the three-man Ireland expedition, paddling 400 miles clockwise from Dublin to Galway. I feel quite comfortable in tidal races and in surf zone and have a good roll.

Albert had been paddling for four years. He has never taken serious advanced kayak training; he can roll but his roll is weak. He has done a couple of kayak trips in Greece and paddled for two weeks in Alaska with a strong group, both in Prince William Sound and in the open sea.

Our plan was to explore the Kenai Fjords launching in Seward, rounding the Kenai Peninsula and taking out after roughly 300 miles at Homer.

FIRST EIGHT DAYS

On the bus from Anchorage to Seward, our driver updated us on the weather situation: “We’ve had a very dry summer this year, very unusual, but now, at last, we’re getting the first real rain.” We could see the dark clouds from the bus window.

At Seward it was already raining heavily and we were informed that the wind outside Resurrection Bay was southeast at 45 knots. Alan, the local kayaker who helped us with the kayaks, commented on that:

“You wouldn’t believe what beautiful weather we’ve had all this summer, but we always knew that when the storm would come, it would come big.”

We decided that even in this weather we could start our trip if we kept to the sheltered water inside the fjords and bays. We left on the next day, knowing that we would stay in Resurrection Bay, until the conditions improved.

We were paddling rented NDK Explorers, the same model that both of us own and paddle at home. Both of us carried NOAA nautical charts of the area on our kayak decks.

We each had a compass mounted on our kayak fore decks. Albert carried a simple waterproof Magellan GPS in his day hatch. He carried a backup GPS, this one a Garmin, packed below deck. I had an Icon waterproof marine radio, kept in a waterproof bag that was attached to my deck.

I also had a Macmurdo PLB (Personal Locator Beacon) with GPS in a pocket on the back of my PFD. In a dry bag deep in my day hatch, I had two aerial flash rockets.

While on the water we both wore drysuits with one layer of fleece and a hat. Each of us used a paddle leash and had a spare paddle on deck.

The constant rain stayed with us for the next eight days, usually accompanied by wind and fog.

We continued our trip, cautiously passing from one fjord to another, always having escape plans ready and usually using them. On one occasion we had high and rising choppy seas and strong wind just before the narrow McArthur passage, but we found shelter safely in Chance Cove that was one of a few escape places that we prepared for that day.

On another occasion we were surprised by the enormous strength of the tidal race at the entrance of the Northwestern Fjord—it was clearly impassable so we camped on the western side of the upper Harris Bay. It was the only place that day without big surf and suitable for landing. We didn’t have a day without a new challenge.

By July 29 we had covered 155 nautical miles and more than half of the distance to Homer.

On that day we camped at Berger Bay on Nuka Island. It was a beautiful gravel beach with a place for the tent and a natural place for our kitchen. We had a fresh salmon that I caught and it was our first camp almost without rain. What else does a kayaker need?

THE PLAN FOR THE DAY

We knew that Gore Point is often a difficult place. It has high cliffs, unpredictable currents and rocks all around. But Gore Point was not our main concern. We worried more about the day following our rounding of the point. On that day we would have to leave very early to catch the flood.

It was the only way to continue west from Gore Peninsula and cover the long distance to reach the first landing spot. To set ourselves up properly for the following day our objective was to pass Gore Point as quickly as possible and to camp at the first place that presented itself.

We knew of one potential campsite, Ranger Beach, located on the west side of the base of the Gore Peninsula. It is a sandy beach and the landing should not be a problem with the usual SW winds. Ranger Beach was located 15 miles from our camping site on Nuka Island.

At that point in the trip we were in good shape and could easily paddle at 4 knots, so the entire way with the favorable wind and current should take less than five hours. That was the good news. The bad news was that the last 11 miles, everything west of Tonsina Bay, offered absolutely no place to land.

It is all high cliffs and we knew very well from the previous days that even in a moderate swell we would do well to stay at least one mile away from the land. We hardly had any rain that evening and our weather forecast, for a change, was not bad.

The last forecast that we got by satellite-phone text message from our weather support man in Israel was for wind ESE at Beaufort Force 3 to 5, and waves at one to two meters coming from SSW.

The VHF reception was very bad at our campsite, but from what we were able to make out seemed to be a forecast that was no different from our satellite-phone forecast.

Before we retreated to our tent that night we watched the northern lights on the horizon. We felt encouraged by our prospects for the following day.

THE GORE POINT DAY

We left our camp on Nuka Island at 1 P.M. The sea was very quiet and there was almost no wind. It was foggy but not too bad; the visibility was about two miles.

We decided to go in the same manner as we did on the previous days—keeping within sight of land. It made navigation easy and we could quickly determine our location based on the shoreline shape and the mountain relief. We headed west and then southwest to Tonsina Bay.

Very soon after we left, we started to feel some wind. It was NNE at Beaufort Force 3 to 4. This direction was unusual and not the forecast. The wind was, however, ideal for us, and I had nothing to complain about having it help push us along.

In about one hour we could see Tonsina Bay on our right side. Our speed was very good, the weather was great and we continued south to Front Point.

On our way to Front Point the wind changed to northeast but still was at Beaufort Force 4. There were only the occasional whitecaps. The only thing that worried us was that the fog was becoming worse.

We could still see the land from about one mile’s distance, but it was behind a hardly transparent screen of fog. We worried that our view of the land could disappear in a few minutes. But the sea conditions were not bad at all at Front Point and we continued to Gore Bight.

The three miles from Front Point to Gore Bight took about one hour and within that span of time everything changed. The wind grew stronger with frightening persistence. In one hour the wind had changed from a friendly Force 4 to a challenging Force 7. The direction of the wind changed as well, shifting from northeast to east.

At 3:30 P.M. we were two miles northeast of Gore Point in a rapidly strengthening wind and in waves reaching eight feet and coming from all directions. We still could see some shape of the land to the north, but the fog obscured any hint of the Gore Peninsula. (The log kept by the captain aboard the nearby fishing vessel Vigilant noted “15:30 … Gore Point, Winds 45 miles per hour, Seas 10 Feet.”)

I had to brace constantly just to stay upright. Albert was much less experienced in a sea like this, and I knew his situation had to be much worse. We were pushed by the wind toward the most intimidating place on the whole Kenai Peninsula. The locals know it as the best location to find interesting debris that has been driven ashore by wind and waves.

It was absolutely clear to me that we were in serious trouble. I called out to Albert, “I think we should call for help.” He quickly agreed.

We brought our kayaks alongside one another. Albert held my cockpit with both hands and I took the VHF radio from my deck and attached it by the wrist strap to the clips in my PFD’s right pocket. Then I switched the VHF on, put it on Channel 16 and pressed the transmit button.

“MAYDAY, MAYDAY, MAYDAY. We are two kayakers two miles northeast of Gore Point. We are still in the kayaks but cannot paddle and we are drifting in the strong wind.”

I had very little hope that anyone would receive our message as we hadn’t seen any other boats since we left Aialik Bay five days ago. We hadn’t seen anyone onshore either.

To my surprise, the call was answered. The blowing wind and the fact that English is not one of my native languages didn’t help. I could understand only part of what came across the radio. I heard: “This is … Star, … specify your position.” I didn’t know who had responded to my call. I replied “Please wait.”

In the strong wind and high waves Albert and I concentrated on keeping the kayaks rafted together. I put the VHF into my pocket, then held Albert’s cockpit while he retrieved the GPS from his day hatch. We couldn’t make any mistakes.

He switched the GPS on and held my cockpit as the coordinates appeared on the GPS screen. I took the VHF out and relayed our coordinates using numbers as well as the words “degrees, minutes, seconds, north, west.” (It was explained to me later that I was expected to use only digits, everything else only made the reception more difficult.)

The VHF came back: “… sending the boat … will come in one hour and fifteen minutes. It is a big black boat; you will see it.” I was not so sure that we would see it in the fog. The hour we would have to wait seemed like a very long time, too long a time.

I looked at Albert: “Let’s activate the PLB.” Albert took the PLB out of the pocket on the back of my PFD, and opened the safety. “The lights are on,” said Albert.

We were so focused on operating our electronics that we didn’t look around even though we knew we were drifting. Albert glanced up, “Gadi, look!”

I looked and saw the landscape looming over the fog. The land wasn’t the coast we’d been seeing to the north. It was to the west. It was the Gore Peninsula. We were drifting very fast in a very bad direction. There was very little chance we would survive being washed ashore on the peninsula. The only solution was to paddle away very fast. We needed to move about one mile south, to avoid getting washed ashore.

I called on the VHF: “This is the two kayaks; we will try to paddle south and get around Gore Point.”

We started to paddle again, bearing ESE to make sure our real progress was to the south. Our effort was mostly against the wind now, and it helped our stability to have the waves coming over the bow. But the farther south we moved, the worse the sea conditions became. It wasn’t surprising. The sea around the end of a headland is always the worst.

It is hard to say how much time passed, but at some point we had the Gore Peninsula behind us. Now, without the danger of being thrown on the rocks, we could try to go to the peninsula’s west side where we would probably be protected from the strong wind and waves.

We continued to paddle west, but the sea was the worst we had met that day. The 11-foot waves coming from the SSE were constantly breaking in the strong east wind. One cresting wave hit me from the left and turned me over. The water wasn’t as cold as I expected.

I noticed it wasn’t as salty to my tongue as the Mediterranean; I felt like I was turned over on a river. My roll is quite reliable, but when I was nearly upright, another blow turned me over once again. I made a much more aggressive attempt and came up expressing my feelings in my native Russian language. I realized that if the waves could capsize me, they could do the same to Albert, and he probably wouldn’t be able to recover by rolling. Albert was on my left and I reduced the distance between us to about 30 feet.

In a few minutes one wave crushed violently on both of us. I did a high brace and survived. Then I looked to my left after the wave passed and saw the white bottom of Albert’s kayak. Albert had bailed out and was holding onto a deck line. The strong wind made it difficult to maneuver alongside him, but I eventually reached his kayak.

I didn’t dare try to empty the kayak, so I just made the rescue and got Albert back into a cockpit full of water. We had a hand pump on my deck and I hoped to use it to empty the cockpit. We rafted up and started to pump. Our success was only partial. We took some water out but the process was very slow, and we had to protect the cockpit from the waves.

I asked Albert if he thought we should try to paddle toward land. He said that he preferred to stay rafted together and wait for rescue. It was quite understandable. The water remaining in his cockpit made his kayak less stable.

The wave that had capsized Albert had washed away his hat and glasses, despite the fact that they were tethered. Albert’s glasses are a very strong prescription and he had never even tried to paddle without them. I looked around and couldn’t see any hint of the land—the fog was obviously stronger than before and, besides that, at the time of the rescue we were drifting out. I looked on the GPS—it was dead, just a black screen. I agreed that the best thing right now was to keep our raft upright and to wait for the rescue.

As we were moving away from Gore Point, the wind remained strong but the seas became more regular. The waves were still big, but now they came from only one direction. A strong rain had started, making the visibility even worse.

We couldn’t put our paddles at 90 degrees to the kayaks. The wind was shaking our raft structure and threatened to take our paddles away. So we had no other choice but to put the paddles under the deck lines. They were not so vulnerable to the wind there, but they were not in the best start position for us if we failed to keep the kayaks rafted and needed the paddles to roll.

We had to pay attention to every wave. It was all about having the right angle of the kayak to meet the wave. All the waves came from Albert’s side. My left hand was on Albert’s kayak and on each wave I pushed the far side of his kayak down.

It was a kind of low brace edging without a paddle that gave us some control of our stability. While we were rafted up we maintained contact with rescuers over the VHF.

“This is two kayaks; we are drifting in strong wind.”

Rescue Ship: “Do you see any land around?”

“Negative, we are in fog; we don’t see any land.”

I later learned that the captain of the rescue ship was not confident that we had actually succeeded in getting beyond Gore Point and was searching for us in the worst place, on the east side of the point. This is why the question about land was asked more than once.

“We activated our PLB. Do you have our position?”

No answer. Some time after, the rescue ship responded: “We turned on our searchlights. Do you see us?”

“Negative, we see nothing. We activated our PLB; do you have our position?”

Rescue ship: “Do you have any flares?”

Deep inside my day hatch I had a dry bag that we got with the kayaks. I knew that we had flares in there but I didn’t think it was worth the risk for one of us to let go of the deck to open the day compartment and grope for the flares. Even if we had been able to find flares, I didn’t believe that they would have been able to see them when we hadn’t been able to see their searchlights.

I replied on VHF: “Negative, we don’t have flares. We activated our PLB; do you have our position?”

The search by the ship continued quite a long time, but they couldn’t find us. Then we got a new message. “A helicopter is coming for you. It will direct us.”

Then after some time we heard a transmission from the rescue helicopter. It was hard for me to understand every word: “… radio … count … ten …“

What I got was enough. “One, Two, Three, Four, Five, Six, Seven, Eight, Nine, Ten. Should I do it again?”

Rescue Helicopter: “… count …”

“Should I count again?”

Rescue Helicopter: “Yes, please count.”

“One, Two, Three, Four, Five, Six, Seven, Eight, Nine, Ten. Should I do it again! Rescue Helicopter: “Yes.”

This back and forth continued for some time.

It was explained to me later that I had been asked to count repeatedly to provide a continuous radio transmission.

Rescue Helicopter: “Great! The signal is stronger now!”

In one minute we saw a big red helicopter coming out of the fog just above us. It was a moment that I will never forget.

“We are in good condition. We can wait for the ship.”

A few minutes later the helicopter dispatched a rescue swimmer.

He approached us with a huge smile on his face: “Hi! I’m Chuck.” It seemed he would jump on our kayaks and shake our hands. “How are you?”

“Albert lost his hat and glasses but we are well.”

“What are you doing here?”

“We are paddling nine days from Seward to Homer. The weather changed suddenly.”

“Where you from?”

“We are from Israel.”

“Israel? Really?! You are quite far away!”

In a few minutes we spotted the Vigilant with all of the searchlights on. It was bouncing up and down on the waves and our first attempt to come to the ship with the kayaks didn’t go well.

But Chuck was very cool and very efficient. We were told to leave the kayaks and climb up using the ship’s tethered life ring. The ship’s crew pulled us aboard. Chuck held on to our kayaks and helped the Vigilant crew haul our boats aboard. In short time we were safely aboard with all of our gear.

It was 6:00 P.M. Two and half hours had passed from the moment we had transmitted our first Mayday.

The fishing boat Vigilant, a 58-foot fish tender, was handled by captain Dennis Magnuson and the deckhand Quinn Tavfer. We couldn’t imagine a better welcome than what we got on the Vigilant.

Fortunately for us, the Vigilant had been nearby in Port Dick Bay collecting salmon from three smaller fishing vessels. We stayed aboard the ship for two days, and when it was full of salmon and ready to head home, we were dropped off at Homer.

LESSONS LEARNED

BE ALERT

We allowed ourselves to be distracted from our safety procedures. Our routine was to get a weather forecast via the satellite phone text message, and listen to the weather radio twice a day to get the regular updates at 4 A.M. and 4 P.M.

Even when we didn’t have reception for the weather radio at our campsite, we still could paddle out from shore and probably have reception out on the water. With the good weather around us, the forecast for fair weather we had gotten a day before and the general feeling that conditions would likely improve after the eight days of rain we’d been through, blunted our senses, and we didn’t maintain the necessary level of alertness.

The radio forecast was drastically changed that day. If we had received it, we would have heard the gale warning. We did ultimately receive the SMS message announcing the change in the weather forecast, but it was received by our satellite phone—when we were already on the fishing boat—after a delay of more than twelve hours.

BE WELL EQUIPPED

Both the PLB and waterproof VHF radio were necessary. If we had had only the PLB and not the VHF, we would have had no knowledge about a rescue being launched until it got to us. At least two hours could have passed while we waited and wondered. I can say that it would have been highly unpleasant.

According to the Coast Guard, the location of a transmitting 406 PLB beacon like we had can be determined within approximately three miles by the first satellite pass, and to within one mile after three satellite passes. In our case of very poor visibility and fast drifting in the wind, it would be very difficult not only for ships but also for the Coast Guard helicopter to find us without the radio signal.

The fact that our VHF radio call was heard by the fishermen was just good luck. The annual salmon season in Port Dick Bay lasts only twenty days in a year. Without large vessels around, our PLB would have been the only means to call for help.

We had flares, but they were stowed deep in the day hatch. In the fog they might not have done much good but, as a rule, safety flares should be kept handy and ready for use.

MATCH YOUR TRIP TO YOUR ABILITIES

Albert is a good kayaker, strong both physically and mentally. However, I knew that he didn’t have much experience in rough seas and that he didn’t have a combat roll. As compensation for that we allowed extra days for our itinerary and decided not to paddle if we were not sure of the conditions. As it turned out, we had bad weather for all nine days and still paddled.

You cannot make any assumptions about the conditions in which you will be in the sea. Even if you listen to the weather radio five times a day, sometimes the forecast still will be terribly wrong. You should be prepared for the worst. For our trip, the solid Five-star training would have been essential for both of us.

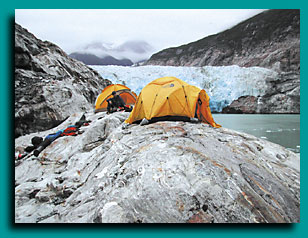

Steep cliffs prevented much hiking, so afterdinner, we watched the glacier, read or retreated to the tents if it rained.

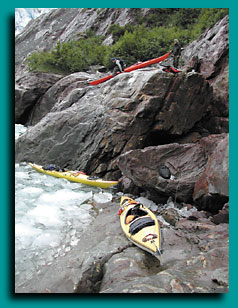

Steep cliffs prevented much hiking, so afterdinner, we watched the glacier, read or retreated to the tents if it rained. enabling me to paddle a mile through sporadic bergs to where the boat had stopped at the edge of another thick ice pack.

enabling me to paddle a mile through sporadic bergs to where the boat had stopped at the edge of another thick ice pack. get pretty close.

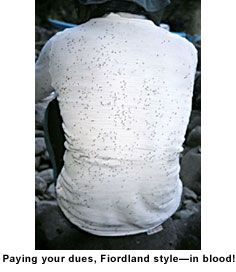

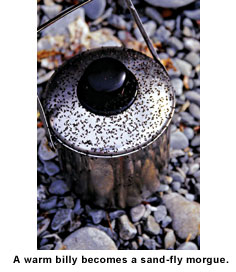

get pretty close. Not that I really felt endangered. With only my hands exposed, I was just impressed that Mother Nature could deliver shock and awe in such small packages. Impressed and annoyed, but mostly itchy. That’s the trouble with fine weather in Fiordland—the sand flies love it too. They especially love fine weather at dusk, in damp, cool tidal creek beds where there is no wind, and Lumaluma Creek, at the head of Fiordland’s Edwardson Sound, in late summer is just that—sand-fly paradise.

Not that I really felt endangered. With only my hands exposed, I was just impressed that Mother Nature could deliver shock and awe in such small packages. Impressed and annoyed, but mostly itchy. That’s the trouble with fine weather in Fiordland—the sand flies love it too. They especially love fine weather at dusk, in damp, cool tidal creek beds where there is no wind, and Lumaluma Creek, at the head of Fiordland’s Edwardson Sound, in late summer is just that—sand-fly paradise. Cooking dinner is a trial, and eating it is equally challenging. While cooking, you can wear a mesh veil and constantly wave your exposed hands around. But eating necessitates removing your veil and exposing your face and neck to the onslaught.

Cooking dinner is a trial, and eating it is equally challenging. While cooking, you can wear a mesh veil and constantly wave your exposed hands around. But eating necessitates removing your veil and exposing your face and neck to the onslaught. escaping. There is no bug-free option to be selected by ticking the box on a booking form. You pay your dues in blood when you visit Fiordland—it’s part of the deal. Just as you can’t experience a tropical rainforest without sitting out a wet-season thunderstorm, so it is with Fiord-land’s sand flies. They’re just as much part of our wilderness heritage as the pristine forest, the imposing mountains and the sheltered inlets. Our paddling paradise, too easily attained, would be devalued without them. And besides, as Maori legend suggests, paradise is intended only for the afterlife.

escaping. There is no bug-free option to be selected by ticking the box on a booking form. You pay your dues in blood when you visit Fiordland—it’s part of the deal. Just as you can’t experience a tropical rainforest without sitting out a wet-season thunderstorm, so it is with Fiord-land’s sand flies. They’re just as much part of our wilderness heritage as the pristine forest, the imposing mountains and the sheltered inlets. Our paddling paradise, too easily attained, would be devalued without them. And besides, as Maori legend suggests, paradise is intended only for the afterlife.

The dessert-like eastern gorge, east of Dalles, Oregon

The dessert-like eastern gorge, east of Dalles, Oregon A rainbow arcs over the mouth of the Klickitat River

A rainbow arcs over the mouth of the Klickitat River Paddlers beneath the waterfalls of Cape Horn in the rainforest at the western end of the Gorge

Paddlers beneath the waterfalls of Cape Horn in the rainforest at the western end of the Gorge Jodi Wright launches into Force-4 winds near Hood River

Jodi Wright launches into Force-4 winds near Hood River Icicles near Stevenson, WA on a cold day of the easterlies

Icicles near Stevenson, WA on a cold day of the easterlies