No, it’s not the latest summer blockbuster. The sacred haunts of the kayaker are being invaded. This is not the familiar invasion of fellow paddlers (a mixed blessing), but a new and more insidious invasion by other species altogether.

Cruise along the northern Mediterranean coast, and you will find that the shallow sea-grass beds that once teemed with life are now a desert of “killer” green algae, devoid of fish and invertebrates. From British Columbia to California, tranquil estuaries that echoed with flocks of migrating birds are now overgrown with acres of new salt marsh, obscuring the shoreline from birds and boaters alike. Along the volcanic rocky shores of Hawai’i, a new barnacle has taken up residence; the coast of South Africa is being invaded by an aggressive intertidal mussel; New Zealand and Australia are unwilling hosts of new seaweeds. Almost everywhere we paddle, old species are being swapped for new.

But new is not necessarily better.

Aliens, exotics, introductions, invaders…they go by many names, but all of these species share the common trait that they are spreading to places they don’t belong. They not only affect kayakers, but snorkelers, scuba divers, fishers, clam diggers, and other boaters. They can carry parasites and diseases. (Some of them are parasites and diseases.) They can damage fisheries, tourism, boating, property values, and industry. They can damage native plants, birds, fish, and mammals and disrupt the very natural world we paddle out to enjoy. That’s the bad news. The good news is that kayakers in particular can help marshal the defenses against them.

Anything can be an alien: seaweeds…

Do you dream, perhaps, of a Mediterranean vacation, floating silently over the teeming life of warm, shallow sea grass beds, trolling slowly for your dinner? When you go, you may catch more seaweed than fish on your line. Along the northern coast of this inland sea, the “killer” green alga called Caulerpa taxifolia is rapidly taking over. Divers first noticed Caulerpa in a small patch outside the Monaco aquarium in 1984. Recognized as a tropical species commonly used in aquaria, no one thought it would survive the cool water temperatures of winter. But this seaweed menace proved more robust than expected, and spread quickly along the coast into France and Spain, and as far east as Turkey.

Today, Caulerpa’s feathery green fronds and snaking root systems cover over 3,000 hectares (7,000 acres) of shallow seabed. And cover they do: rocks, sand, mud, seagrass beds; nothing is safe from its encroachment. Although Caulerpa is not toxic to humans, fish and sea urchins avoid it and seek more familiar ground-no easy task, when Caulerpa covers up to 100% of the ground, down to a depth of 35 m (114′). So much for catching dinner.

…plants…

Perhaps you are eschewing a sun-drenched holiday to explore the misty rainforest estuaries of the Pacific Northwest? Beware the invading smooth cordgrass, Spartina alterniflora. A beloved native of the east coast’s signature salt marshes, this grass is now a scourge of west-coast estuaries, where its characteristic circular patches expand across the tidal flat and displace native mud-dwellers.

Smooth cordgrass in the Pacific was first discovered in Willapa Bay, Washington, in the late 1800s. Its precise origin remains a mystery, but it was probably introduced accidentally, mixed in either with oyster shipments or with the rock and dirt ballast of wooden sailing ships. Spartina was later planted in other Northwest bays to control erosion and create duck (and duck-hunter) habitat.

Simply by growing along the water’s edge, smooth cordgrass drastically alters the shoreline. Its tall, stiff stems and long green leaves slow the flow of water, causing sediments to build up so high that the growing marsh is raised above the tideline. The semi-terrestrial meadow is no longer a suitable habitat for certain intertidal clams, for clam diggers (there goes dinner, again), or for the thousands of migratory and resident birds that depend on these estuaries for food. Boat access is affected too: with the ocean now farther away, you can no longer simply slide into your kayak from your backyard.

Invasive tendencies seem to run in the family: a second species of Atlantic cordgrass is also invading the Pacific, a South American cordgrass is invading North America, and worst of all, an English cordgrass planted widely in Europe, China, and Tasmania, is spreading rapidly around the world.

…animals…

Headed instead for the languid, coffee-colored waters of the Mississippi bayou? Keep your eyes open for nutria (Myocastor coypus), an overgrown swamp rat that may appear on the riverbank or even on a restaurant menu. These 20-pound nocturnal rodents were introduced from their native South America to the Gulf coast and southeastern states in the 1930s and ’40s for their fur, and at one time a breeding pair fetched up to $2,500 US.

Unfortunately, the demand for nutria fur can’t keep up with their vigorous population growth: a female typically matures at 5-8 months, producing litters of 4-6 young up to twice a year. Their predators-mostly alligators, but also turtles, gar, cottonmouth water moccasins, hawks, owls, and eagles-can’t keep up either. As a result, these hungry rodents, each armed with inch-long orange incisors, are excavating the coastal marshes and riverbanks of the Gulf States. A single animal can eat up to 25% of its body weight in plants per day. Not only does this activity destroy coastal vegetation, but it also reduces habitat available for native muskrat and waterfowl. Nutria also venture inland, devouring rice, sugar cane, soybean, alfalfa and corn crops and burrowing through protective levees.

In addition to their voracious appetites, nutria carry a parasitic roundworm, or nematode, whose larva can burrow into human skin, causing a severe “marsh itch” or “nutria itch” requiring medical attention.

…even microscopic diseases.

Some invaders are much smaller, but no less destructive. Beaches everywhere are increasingly closed to clam and mussel harvest, with posted signs warning of red tide, the blooms of toxic single-celled algae that cause paralytic shellfish poisoning. These outbreaks have recently been associated with the global transport of ballast water in commercial vessels. A ship that takes on water in a bloom area may carry the algae to a new port, initiating a new outbreak there. Indeed, the resting stages of toxic algae have repeatedly been collected from the sediments in ballast tanks of ships sailing into Australian waters.

Viruses and bacteria are carried too: over 90% of the ships entering Chesapeake Bay carry epidemic cholera in their ballast tanks, and in 1991 cholera was introduced to Mobile Bay, Alabama, in the ballast water of a ship sailing from South America.

Not just in the sea

Aliens are also invading lakes and rivers, forests and fields. Paddling in the North American Great Lakes, you will encounter infestations of the European zebra mussel fouling beaches, boat hulls, piers, and power plant water intakes. The native plankton-eating fish you see in the water below you are competing with a tiny, spiny European water flea for food. That appealing-looking beach may in fact stink with piles of rotting alewife, an introduced coastal fish that also competes with native chub and whitefish. Salmonids, introduced partly to control alewife, are in turn eaten by introduced lamprey. And the lamprey prey on other fish, including steelhead (introduced) and walleye, whitefish, and burbot (native).

Fish introductions are altering freshwater foodwebs around the world, and waterways everywhere are clogged by introduced aquatic plants like purple loosestrife, hydrilla, water-hyacinth and Eurasian milfoil.

You will encounter plant and animal invaders ashore, too. In California, you may clamber over South African ice plant to pitch your tent under an Australian eucalyptus tree. When you unroll your sleeping pad in Hawai’i, you keep a wary eye out for South American fire ants; in South America, for Africanized killer bees; in Africa, for the thorns of Australian acacia trees; in Australia, for the dung of European sheep. It seems that certain species, like certain familiar fast-food joints or soda brands, may soon spread to every place you travel.

An accelerating problem

As invaders accumulate, they stamp out the uniqueness of an ecological community, and convert it to an international hodge-podge of aggressive competitors and predators. Over 40 species of marine invaders are found in Chesapeake Bay, over 50 in Coos Bay, Oregon, over 90 in Port Philip Bay, Australia, and over 100 in the Great Lakes, San Francisco Bay, and the eastern Mediterranean. As a unit, they represent one of the greatest threats to endangered species in the U.S., second only to habitat loss, to which they also contribute. Their estimated costs in control and eradication run into the billions of dollars annually, in the U.S. alone. And the flood of new arrivals shows no signs of slowing. How do these species become such a problem?

Planes, trains and automobiles

By definition, an invasion doesn’t happen by itself. It needs help, and that help – be it intentional or not -usually comes from humans. Every species is native to some place in the world where it belongs. Any species that travels to another place, a place it could not walk, swim, hop, jump or fly to by itself, is labeled introduced. And these species travel the same way we and our stuff do: in airplanes, boats, cars, trucks, packages, and sometimes even our pockets.

Accidental tourists

Let’s start with boats. Commercial ships carry thousands of tons of ballast water, port water that is pumped through hull openings into tanks that keep the ship stable at sea. This ballast water typically teems with tiny larvae, the microscopic stages of sea life, that are readily sucked up into a ballasting ship, transported farther and faster than they would naturally drift in ocean currents, and then emptied out into a new port. Zebra mussels are perhaps the most famous ballast-water invader, arriving in North America from Europe in the mid2980s and costing an estimated $5 billion in control efforts over 10 years.

Traveling in the other direction, the North American comb jelly, Mnemiopsis leidyi, sailed to the Black Sea at around the same time. Swimming like a predatory vacuum cleaner, this jelly’s population soared as it swallowed up larval fish and the microscopic organisms the fish eat. In the wake of this double whammy, commercial fisheries around the Black Sea crashed precipitously.

Historically, ships carried not water but dry ballast, port-side rocks and dirt full of plants, seeds, and insects, that was dumped out at the next beach, often a continent away. And unlike modern steel hulls coated with anti-foulants, older ships had wooden hulls riddled with species of ship worm, sponge, seasquirt, and seaweed that are now found the world over.

As ships were developed to carry water, so water was rerouted to carry ships. From the mid2800s to the mid2900s, water bodies that had been isolated for millennia were suddenly connected by canals. In 1869, the Suez Canal joined the Red and Mediterranean Seas; in 1914, the Panama Canal linked the Atlantic and Pacific; through the 1950s, the St. Lawrence waterway pushed west from the Atlantic to Lake Superior. Over 25,000 kilometers (15,500 miles) of canals now link the river cities of western Europe, stretching as far inland as Georgia. And where ships could sail, so too could-and did-fish swim and larvae drift.

Recreational boats, including kayaks, typically don’t carry water ballast, but they can carry a host of organisms on their hulls and trailers. Zebra mussels, for example, can survive out of water for days and their spread through lakes of North America is closely tied to patterns of boater traffic.

nvited invaders

Species introduced in ballast water are inadvertent hitchhikers, but other invaders are introduced on purpose. Like agriculture on land, the industry of aquaculture ships marketable species worldwide. Thus, Japanese oysters have been grown in Europe, Canada, the U.S., China, Korea, New Zealand and Australia. Mediterranean mussels are grown in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. In the U.S., Atlantic lobsters were introduced to the Pacific coast and Pacific clams to the Atlantic.

For commercial and recreational fisheries, the story is similar. Atlantic shad were shipped to San Francisco in the 1870s and spread rapidly up the coast to British Columbia. Pacific salmon now thrive in the Great Lakes. Atlantic salmon, which failed to establish despite repeated introductions in the early 1900s, have now escaped from net pens and are reproducing in the rivers of Vancouver Island. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, European carp were shipped enthusiastically to ponds and streams across North America; today, brown trout and rainbow trout are still stocked in non-native locations.

Along with these intentionally introduced species have come a host of hitchhikers: for example, some fifteen species of clam, snail, and other invertebrates were inadvertently introduced to the Pacific Northwest with Atlantic and Japanese oyster shipments, including at least three oyster predators and parasites.

On land, invasion pathways are broadly similar: inadvertent introductions, intentional introductions, and their hitchhikers. Plants and insects travel in shipments of wood and produce, on car tires, in train cars. Ornamental plants are introduced, and soil nematodes come with them. Invaders sneak in as unseen pests in the fruit in our luggage, and are imported for biocontrol of agricultural pests, which are often invaders themselves as well.

Reducing the risk

Around the globe, humans are, inadvertently and intentionally, smearing the world’s species across their natural boundaries and homogenizing communities that were once distinct. In the process, we are generating a host of health and environmental risks. How can we slow this onslaught? First off, not all introduced species survive. Of those that do, not all spread vigorously or reach pest proportions, and many go unnoticed for decades.

The trouble is, the science of predicting which invasions will be successful is only just beginning. Once a species has arrived, controlling it is typically neither pretty or, often, effective. It may take years of physical work, chemical application, and sometimes even the introduction of other, non-native predator species.

Since we do not yet know reliably which invasions will be benign and which disastrous, and since control efforts are at best challenging and at worst cause even further problems, the best way to avoid harmful and expensive future problems is to prevent species from invading in the first place. Luckily, since humans are doing the introducing, humans can also stop it.

Don’t be a vector

On land, some of these precautions are already evident. When you return to the U.S. mainland from Hawai’i, your luggage is inspected for fruit pests that could damage mainland crops. When you fly into certain countries, your airplane may be sprayed with insecticides. During the current hoof-and-mouth epidemic, even Prince Charles had to wipe his feet upon arrival in the U.S. On a smaller scale, we can implement our own preventive standards for the places we explore.

The simplest guideline is this: Don’t be a vector. Invasive species get transmitted just like the flu does-by people. The same reason you stay home from work when you’re ill (or at least, that’s what you tell the boss as you pack up your dry bag) is the reason to leave other species at home when you travel. You are protecting the places you visit and the native species that live there. Both during and between trips, four simple tips can help reduce the risk of invasions.

On trips:

1. Report any unusual plants or animals in your local waters to your area fish and wildlife department, aquarium, or university. Study posters and other materials at marinas to recognize invaders in your area. By keeping an eye out for new arrivals, you can play an important role in invasion early warning.

2. Rinse off hulls and trailers at the take-out site to avoid moving pesky hitchhikers from one water body to the next (on any kind of boat).

3. Wash tents and other gear between trips to remove unwanted seeds and pollen grains. In the same way, rinse off your boots before exploring inland on your next trip. You can even wash off your car tires before visiting national parks and other protected areas.

4. Bring your unused bait home rather than dumping it: even if you can’t see them, live non-native species may be present on baitshop bait.

Between trips:

1. Don’t dump “live” trash. When you purchase shellfish from the store, throw the empty half-shells in the garbage, not onto the beach. Even if the shells look clean, they may be host to some non-native hitchhikers. Similarly, if you order live shellfish or other organisms for restaurants, classrooms, or anywhere else, throw the packing material in the garbage (even if it’s live plants or seaweed). Don’t risk starting an invasion.

2. Don’t release your pets into the wild: goldfish (or any other fish), birds, cats, dogs, and other animals can become feral, with devastating impacts on native species. In Hawai’i, for example, introduced avian malaria and feral cats are together driving native birds extinct. For the same reason, if you purchase lobster or any other live shellfish, but at the last minute can’t bring yourself to throw them in the pot, don’t release them at the shore-give them to a neighbor instead.

3. Seek out native trees, shrubs and flowers when you visit a garden nursery. Avoid planting exotics-they may use your yard as a launch site for a new invasion.

4. Get involved in local restoration projects to eradicate invaders and re-establish native species. Many local, regional and national parks will be delighted to have your help.

Whether we’re out on the water for an afternoon, a weekend, or a month, our motivation is the same: to see the land and seascape from a different perspective, to enjoy proximity to the natural world. But by doing so, we can inadvertently contribute to damaging this resource, our health, and our economy. Introduced species are an expensive and environmentally devastating challenge; kayakers are in a unique position to help reduce the risks.

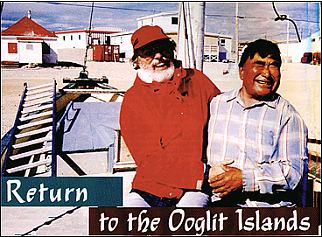

Igloolik-A grand re-union with some old hunting pals. Here Enuki Kunnuk and I share a laugh about who was better fed over the years and who got older looking…In the background is the town of Igloolik. The small white building with the red roof is one of the last of the former Hudson’s Bay Company buildings remaining from the old days of the north.

Igloolik-A grand re-union with some old hunting pals. Here Enuki Kunnuk and I share a laugh about who was better fed over the years and who got older looking…In the background is the town of Igloolik. The small white building with the red roof is one of the last of the former Hudson’s Bay Company buildings remaining from the old days of the north.

It had been a brief visit, but it was vividly etched in my memory. This was finally my chance to return. I would paddle from Hall Beach to Igloolik and, along the way, stop at the Ooglit Islands.

It had been a brief visit, but it was vividly etched in my memory. This was finally my chance to return. I would paddle from Hall Beach to Igloolik and, along the way, stop at the Ooglit Islands.