A group of friends from the Sea Kayaking Club were wrapping up a four-day trip in the Apostle Islands. They had successfully avoided a few isolated rain showers, but were caught off guard by the cold nights.

Their sleeping bags were simply not warm enough, and everyone was sleeping poorly. To make matters worse, they forgot to bring coffee, which made each morning a little rougher. As the sun came up on the last day of their trip, tempers were short, and while it had been nice to be out in the wilderness for a few days, everyone was ready to get back to the mainland.

The weather radio indicated a forecast that was near the limit of their skills, with rain expected for the afternoon and evening. Everyone was a bit edgy, and the decision to launch was made with minimal discussion since no one wanted to spend another day camping. Halfway through the crossing, they realized that they were in over their heads and wished they had stayed ashore.

Nearby, Adventure Kayaking Club paddlers had enjoyed a weekend out on the water. They had camped close to the group from the Sea Kayaking Club. As the sun rose on a crisp Sunday morning, the group started to move around, enjoying a hot cup of coffee and some breakfast to start the day.

A warm fire provided welcome relief against the cold. Enjoying breakfast together, they listened to the weather forecast. Conditions were within their abilities, but with a minimal safety margin. Their campsite was in a protected cove with a nice view of the surrounding islands, so they were in no hurry to leave. After some discussion, they declared it a “wind day” and made plans to go hiking while the new weather front moved through the region. At midday, from a viewpoint at the apex of the island they saw that the water was quite rough and were glad to be ashore.

Economics of Decision Making

In these hypothetical examples, why did the Sea Kayaking Club launch while the Adventure Kayaking Club opted to stay ashore? In most discussions of the mistakes kayakers make, the focus is on understanding the risks faced by the paddlers on the water and their ability to correctly evaluate and/or overcome them.

This line of inquiry is incomplete because it does not account for how risk is perceived and it fails to take into account how we actually make the decision to launch.

Most paddlers would agree that the efforts that go into getting ready for a trip are, in economic terms, an investment, and the pleasure of paddling is a return on that investment.

If you’ve spent a week getting ready for a big trip and then drive five hours to the launch site, you’re going to be very eager to get on the water—paddling is the return on your investment. During a long cruise, each successful launch during the trip brings you closer to your goals and improves the return on your investment.

If being out on the water seems like the best use of our time, we launch. Since every kayaking incident starts with the decision to launch, it follows that our safety on the water is influenced by the alternatives that are available to us at launch time.

While reading reports of kayaking incidents in the past few years, I became convinced that something fundamental was missing in how kayakers made decisions to launch in marginal circumstances.

Having recently completed my MBA, it occurred to me that concepts from economics and consumer behavior could be applied to better understand how we make our decision to launch. I realized that things we consider to be optional when preparing for a trip should actually be considered as playing an important role in safety.

It also became clear why many attempts at discouraging kayakers from launching into deteriorating conditions are unsuccessful, and how that can be improved.

There are some economic terms that you might be able to apply to decision making at the start of a paddling day:

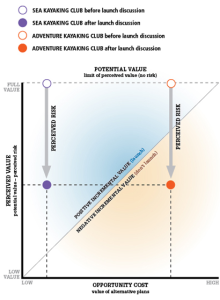

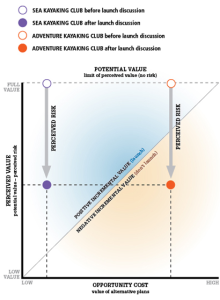

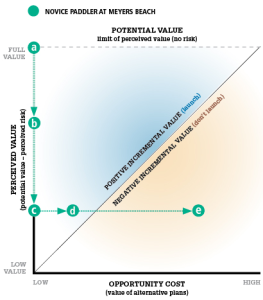

Before their respective launch discussions, both groups had the same potential value (returning from the trip) and the same perceived risk (weather forecast and skill levels), so the perceived value of launching was the same.

Before their respective launch discussions, both groups had the same potential value (returning from the trip) and the same perceived risk (weather forecast and skill levels), so the perceived value of launching was the same.

The Sea Kayaking Club had a lower opportunity cost, so they stayed in the blue “launch” zone—their incremental value remained positive.The Adventure Kayaking Club had a higher opportunity cost, which moved them farther to the right into the tan “don’t launch” zone.

Their opportunity cost exceeded their perceived value, resulting in a negative incremental value. This meant they should forego the launch and stay on land, since that was the more valuable of the two options.

Potential value: The amount of enjoyment you might have or the goals that you’ll achieve by paddling today.

Perceived risk: The downsides of paddling today—the things you will not enjoy or that might harm you.

Perceived value = potential value minus perceived risk: Is the payoff worth the risk or effort you take on? If the potential value clearly outweighs the perceived risk, the perceived value is high.

Opportunity cost: What else could you be doing if you chose not to paddle today? Could a day ashore be time well spent?

Incremental value = perceived value minus opportunity cost: How much more will you enjoy paddling over whatever else you could be doing? This is the difference between perceived value and opportunity cost.

Potential Value

The potential value is where we typically focus when deciding whether to launch. This includes both the experience of being out on the water—seeing cool sea caves, surfing in moderately sized waves—as well as what might be gained from achieving the day’s objective—getting to the campsite, completing the trip on time.

Economic theory says that the effort we put into getting ready for a trip should have no bearing on the launch decision. It is referred to as a “sunk cost,” meaning that we have already spent our time and resources in such a manner that it cannot be undone.

As paddlers, we often view the work of packing and getting to the put-in as an investment, which puts additional pressure on us to “protect” that investment when we arrive at the launch. This is a dangerous perspective. No matter how much we’ve invested in getting to the water, a bad launch decision is still a bad launch decision; it is in no way excused because we worked hard to make it possible.

Perceived Risk

When evaluating conditions, the skill level of the paddler is important because a heavy reliance is placed on previous experiences. Thus, risk assessment is subjective in nature because it is the perception of risk that drives our decision. There are two factors that affect how we perceive risk.

First, we are much more willing to accept a risk when it is voluntary. Voluntary risk is why people believe they are safer driving cars versus flying in an airplane, even though the airplane is statistically much safer. It turns out we feel comfortable with significantly higher risks when we feel in control of our fate.

This is important, since it distorts how we evaluate risk. I have happily launched in conditions when I felt it was my decision to make, but was opposed to launching in similar conditions when someone else was pressuring me to do so.

Next, we evaluate risk by comparing it to something we know, and extrapolating when it lies beyond the boundaries of what we have already experienced. Unfortunately, we tend to underestimate significantly the additional risk that lies outside of our experience.

Experienced paddlers know that key variables for paddling difficulty are wave height, wind speed and the paddling direction relative to the wind and waves. We listen to the weather forecast and try to extrapolate the conditions based on what we have already experienced.

When evaluating conditions, I might think, “Hmm, that’s kind of like a crossing I did last summer, but the winds are going to be a bit stronger so it will take longer.” The smaller the gap between what we have experienced and what we are considering, the more likely we are to correctly evaluate the new situation.

Since we underestimate risk when extrapolating, novices are especially bad at assessing the risk associated with adverse conditions they encounter for the first time.

Evaluating the additional risk when moving from paddling on a small city lake in calm conditions to making a two-mile crossing with 15-knot winds and three- to four-foot waves is a jump beginners simply cannot make. As a result, the weather forecast may have limited value because new paddlers cannot comprehend the associated risk.

Making matters worse, they may not be aware of their limitations, which can make it very difficult, at best, for a concerned paddler to have a conversation with them about the risks associated with launching in challenging conditions. The result may be an “I know what I am doing” response, since they may not even be aware of the fact they can’t fully understand the situation. In such a situation, the perceived risk associated with launching is low for the new paddler, since they lack the knowledge needed to correctly interpret what it will feel like on the water once they launch.

Note that I use the term “perceived risk” here to signify possible negatives associated with the trip. Large waves may not be a negative for everyone, but the possibility of having to call for a rescue certainly is.

Perceived Value

Perceived value starts with how much we might enjoy paddling today and accounts for the associated risk. The result is how much we reasonably expect to enjoy paddling today.

Bringing the components—potential value and perceived risk—into play makes it easier to bring our traditional kayak-focused discussion of risk into this economic framework.

Opportunity Cost

Although an accurate assessment of risk is a key step when deciding to launch, the opportunity cost is always considered—either explicitly or implicitly. This explicit discussion is often missing when discussing the launch decision at the beach.

As mentioned above, the opportunity cost is what the alternative use of our time will be if we don’t go paddling now. The higher the opportunity cost, the higher my requirements are for a fulfilling time paddling. The experience of staying on the beach has some level of value and the better prepared you are to enjoy the time you spend ashore, the higher that value is.

Giving up something that has a high value implies a high cost for the activity you choose. Good alternatives to paddling have a high opportunity cost.

In the example I created at the beginning of this article, the Sea Kayaking Club was cold and tired, and staying at their campsite to wait for better paddling weather was going to mean more of the same, creating a low opportunity cost. They could imaginebeing uncomfortably anxious paddling in marginal conditions, but they knew staying ashore surely meant even more discomfort because of the cold.

A few miles away, the Adventure Kayaking Club had a great campsite, where all were warm and well rested. They were quite happy, and staying in camp would continue to be enjoyable. For them, there was a high opportunity cost associated with launching, since they knew they would be leaving a good thing behind. Since the opportunity cost of staying (warm and happy) exceeded the low value they saw in launching (high degree of anxiety), it was easy for them to opt to stay on land for the day.

Incremental Value

Understanding perceived value and opportunity cost brings us to the idea of incremental value. A decision to launch goes through these steps:

How much are you going to enjoy or gain from going padding?

Weigh the negatives associated with the paddling (e.g., potential for strong winds and large waves, or the chance of rain).

Compare your experience if you go paddling to what else you might do instead.

The gain you might realize by going paddling versus doing something else is your incremental value. The larger the incremental value, the more likely you are to launch.

Consider when launching whether the incremental value is high for the right reasons. Is it high because the paddling conditions are great, or because your current situation is miserable and almost anything would be better than staying where you are? The incremental value should be high because the expected value is high—anything else is a red flag.

Wind Day at Pukaskwa National Park

A few years ago I was paddling with a group of friends at Pukaskwa National Park on Lake Superior. We were five days out and had not seen anyone since launching. Everyone in the group was an experienced paddler. The winds had come up overnight, and it was clear that there were significant waves (five to six feet) and whitecaps out past the protection of our cove.

We discussed the pros of launching—we wanted to make some miles to reach a specific point in the park in order to complete the entire trip within our allotted time. Paddling in big waves all day was going to be challenging and introduced some risk, but it was within our abilities (albeit with various individual safety margins).

Finally, we began to discuss the alternative. “If we stay here, what are we going to do today?” The group grew quiet, since the opportunity cost was low. No one was excited by the prospect of spending the day just “sitting on the beach.”

One person in the group noted that the wind was blowing into the cove, so the waves were coming in as well. It would be an excellent day to go play, since in the event of a wet exit the waves at the mouth of the cove would simply push us back to the calm water inside.

Not moving camp would allow for some free time: an enjoyable happy hour later in the afternoon complete with freshly made guacamole by our resident gourmet chef. With those observations the opportunity cost increased dramatically, causing the incremental value of launching to become negative.

A few moments later, everyone enthusiastically agreed that staying at the campsite and playing in the cove was the right decision to make. The perceived risk of the situation never changed, only our awareness of the alternatives available to us if we did not launch. By considering those alternatives, the incremental value of paddling went from marginal to negative, making the smart choice clear.

The opportunity cost is important to keep in mind when planning a trip. Think of good food, an interesting book, and comfortable accommodations as your insurance policy. These “luxuries” will help protect you from being forced into unsafe decisions by a positive incremental value for paddling that is elevated simply by discomfort and/or boredom in camp.

Chain of Events

Safety on the water is important, but the situation off the water has a huge influence on our decision to be out on the water in the first place. The better the situation on land, the higher our opportunity cost. The higher our opportunity cost, the less likely we are to launch in marginal conditions.

A low opportunity cost at the time of launch is an often overlooked link in the chain of events that leads up to an incident. Too often the focus of accident analysis is on gear or skills that failed to meet the challenges that arose on the water. The decision to leave the beach is always at the root of an incident and the conditions we make for ourselves on land play a large part in that decision.

The following all contribute to the chain of events that lead to a low opportunity cost at the time of launch:

Good Planning and Preparation

Wind day options: What will everyone do on a wind day? No one should be itching to go because they’ve worked hard to get to the put-in or are bored after spending a day or two at the same campsite. While you are home making plans, be sure to investigate the alternatives available if conditions are poor when you arrive at the launch site, making it unwise to launch. Prepare yourself to spend your wind days comfortably in camp. A very experienced kayaker I know once told me that a good book is his most important piece of safety equipment, because it prevents him from launching in marginal conditions simply because he is bored.

Scheduling flexibility: A pressing reason to be back on the expected date of return skews the incremental value of launching before the kayaks are ever loaded. The perceived value of completing the outing at a certain time to meet family or work obligations dramatically inflates the perceived value of launching.

This frequently leads to trouble. Wind days must be accounted for, and a plan should be in place if the group is running a day or two late.

I was on a trip recently where seven- to nine-foot waves were forecast for Saturday night into Sunday morning.

The winds would subside Sunday around noon, but it was unclear when the seas would settle enough for safe paddling. We’d planned to spend that night at an island offshore, but because my friend had to be back at work on Monday, we opted to forgo camping on the island. It was a tough decision to make because the water was still flat late Saturday afternoon when we had to weigh our options.

We stayed on the mainland and did some day trips rather than force ourselves into a bad situation Sunday afternoon if the conditions were marginal. This turned out to be the right choice when the wind began to blow that night.

Happy Group

Personalities: When the personalities get along well, everything else seems easy. When they don’t, your group has lowered the opportunity cost, since paddlers would rather be out on the water than stay in camp with people they don’t like.

Communication: Talking is the key to staying in sync as the trip evolves. I find that setting aside a time of day (at dinner, over the campfire) to talk about the day and expectations for tomorrow keeps everyone in tune with the situation. Poor communication can quickly create a situation with lots of drama, lowering the opportunity cost at launch time.

Good Campsite

Site: Avoid choosing a site where you have to move the next day simply because you can’t stomach the idea of spending an additional day there.

Explicit discussion: What will we do if we call a wind day tomorrow? Is this where we want to be, or is a different campsite the better choice? On a recent nine-day trip, the forecast indicated 12- to 15-foot waves with 40-knot winds for the next day. That afternoon, we specifically chose a campsite with those conditions in mind. It ended up being a great choice, since we were protected from the wind and had lots of room to move around.

Influencing the Launch Decision for Others

It’s one thing to make better decisions as a group, but what can you do when you come across other paddlers (especially those you don’t know) getting ready to launch in questionable conditions?

You might try to initiate a discussion that focuses solely on the risks involved. This is ineffective with new paddlers, because they lack the personal experiences required to assess risk correctly. A better approach is to influence the perception of risk, and the opportunity cost associated with launching.

My friend Dave came across a paddler getting ready to launch near Meyers Beach in the Apostle Islands. Conditions were windy, and Dave knew that several paddlers have died exploring the sea caves in that area when their boats flipped and they found themselves in the water.

Dave tried to explain that capsizing in Lake Superior without at least a wetsuit is a bad idea—the 45˚F water quickly leads to hypothermia, making it nearly impossible to get back into the boat. The paddler was not convinced. Dave asked him to stand in water up to his knees while they continued their conversation.

After a minute, Dave asked if he could still feel his legs and was told “no.” Dave then asked him how effectively he would be able to get back into his boat if his whole body felt as numb.

The paddler now had a new personal experience that made the knowledge gap much smaller, allowing him to assess the risk more effectively. His potential value remained the same—the sea caves are cool—but his perceived risk just increased, resulting in a reduced perceived value.

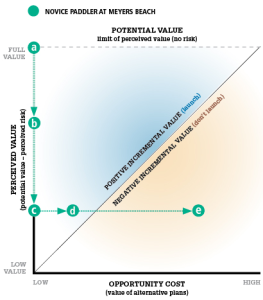

In the example of the exchange between the experienced kayaker—Dave—and a novice, the conversation began with Dave’s effort to increase the novice’s existing perception of the risk (a to b) by discussing the dangers of falling into the water without a wetsuit.

In the example of the exchange between the experienced kayaker—Dave—and a novice, the conversation began with Dave’s effort to increase the novice’s existing perception of the risk (a to b) by discussing the dangers of falling into the water without a wetsuit.

The novice’s perceived risk increased slightly, resulting in a lower perceived value. The trip maintained a positive incremental value, so Dave had him stand in the cold water. This imparted a direct and personal understanding of what capsizing in those conditions would be like, raising the perceived risk more, which further lowered the perceived value (b to c).

Unless the opportunity cost is addressed, Dave faces a monumental task of increasing the perceived risk to a level high enough to eliminate all perceived value—he must convince the novice that launching will result in a rescue or worse. In practice, that’s not likely to happen because the novice simply cannot understand all of the risks involved.

Faced with the option of being bored, most people will downplay the risk and opt to launch. The novice may have considered sitting on the beach and watching the waves for a while, but that only shifted him partway to the “don’t launch” zone (c to d).

Dave provided a more attractive alternative to the proposed launch, which raised the opportunity cost enough (d to e) to convince the novice to abandon the original plan and launch in more protected waters. Although Dave’s focus was on the safety of the novice, explaining the risk was only part of the eventual solution.

The paddler was new to the area and had no idea what else he might spend the afternoon doing, so his opportunity cost was pretty low—just sitting on the beach was of little interest. The incremental value was still positive, but had become marginally so.

Dave next addressed the opportunity cost. He suggested checking out the Bark Bay Slough, about five miles down the road. It’s sheltered from the wind and an interesting place to explore via kayak. This sounded interesting, so the opportunity cost provided by the alternate destination went up.

The incremental value of exploring the caves became negative and not launching made the best sense. The alternative destination was now the better choice. The paddler decided to load his boat back onto the car and drive down to Bark Bay instead.

Conclusions

The decision to launch is the last decision in a chain that starts with trip planning at home and continues on to our environment at the time of the launch. By focusing on each step along the way to ensure we always have an enjoyable backup plan, we are more likely to avoid launching in marginal conditions.

Understanding the components of this process also enables us to be more effective at helping others understand the implications of launching in poor conditions.

Discussing risk is a good starting point, but the incremental value will be decreased more effectively by suggesting interesting alternatives. It is the awareness of those alternatives that may persuade both new and experienced kayakers to come back and paddle on a better day.

To seal themselves into the cockpits of their kayaks, the Native Greenland paddlers often use a tuiitsoq.

To seal themselves into the cockpits of their kayaks, the Native Greenland paddlers often use a tuiitsoq. The seams of the Brooks tuiliq are glued on the inside and sewn on the outside. Its hem has a rubber-side-out sleeve around a bungie cord that seals the tuiliq to the cockpit coaming.

The seams of the Brooks tuiliq are glued on the inside and sewn on the outside. Its hem has a rubber-side-out sleeve around a bungie cord that seals the tuiliq to the cockpit coaming. Before their respective launch discussions, both groups had the same potential value (returning from the trip) and the same perceived risk (weather forecast and skill levels), so the perceived value of launching was the same.

Before their respective launch discussions, both groups had the same potential value (returning from the trip) and the same perceived risk (weather forecast and skill levels), so the perceived value of launching was the same. In the example of the exchange between the experienced kayaker—Dave—and a novice, the conversation began with Dave’s effort to increase the novice’s existing perception of the risk (a to b) by discussing the dangers of falling into the water without a wetsuit.

In the example of the exchange between the experienced kayaker—Dave—and a novice, the conversation began with Dave’s effort to increase the novice’s existing perception of the risk (a to b) by discussing the dangers of falling into the water without a wetsuit.

When my Danish friend Olaf Malver rang me up and asked me if I wanted to join a select group of paddlers going to Antarctica for an exploratory sea kayaking trip, I ran to pack my cold-weather paddling gear.

When my Danish friend Olaf Malver rang me up and asked me if I wanted to join a select group of paddlers going to Antarctica for an exploratory sea kayaking trip, I ran to pack my cold-weather paddling gear. We soon discovered that the stories we had all heard about this Southern Ocean were not exaggerated. These seas seemed charged with conditions more immense, more powerful than those through which any of us had ever drawn a kayak paddle.

We soon discovered that the stories we had all heard about this Southern Ocean were not exaggerated. These seas seemed charged with conditions more immense, more powerful than those through which any of us had ever drawn a kayak paddle. My paddling partner, Lou Gibbs, and I landed our kayak on a narrow strip of sandy beach near the crumbling remains of the whaling station, while the other paddlers explored the waterfront by kayak.

My paddling partner, Lou Gibbs, and I landed our kayak on a narrow strip of sandy beach near the crumbling remains of the whaling station, while the other paddlers explored the waterfront by kayak. In Greenlandic, the word ‘maligiaq’ means “medium-sized wave.”

In Greenlandic, the word ‘maligiaq’ means “medium-sized wave.”