I dipped my paddle into the crystal-clear water, and my kayak glided over branches of brilliant red, purple and orange coral. Schools of shimmering fish darted out from under my bow. The transparency of the aqua water made it seem as if my kayak was floating on air, hovering over the reef. I was surrounded by dozens of tropical islands, their brilliant green foliage rising from white sand beaches to jagged peaks. Suddenly, just off my bow, I spotted a scurry of activity in a tidal pool on the shoreline of a large island. A band of wild monkeys was “fishing,” flipping rocks in their search for food. They hadn’t noticed my approach. As I glided silently along, it seemed as if I would be able to slip in close to them, but then I was spotted. With splashing and a flurry of motion, the monkeys raced for the cover of the jungle. While I couldn’t see them in the thick foliage of the trees, the monkeys’ chattering seemed to indicate their displeasure at being so rudely interrupted. I retreated so that they could resume their tidal feast.

Paddling away, I was gripped by a sense of awe that I was actually here.

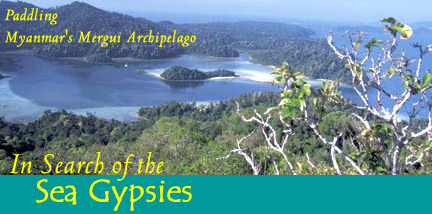

It had been only a few short months ago that Myanmar was just a place I happened to notice on a globe. One of my favorite pastimes is poring over a globe and maps, searching out new places for adventure. One night, I happened to notice a cluster of islands off the coast of Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. The island grouping is called the Mergui Archipelago. My interest was piqued but, when I began researching the islands, there was little information to be found. The Burmese government had banned tourism for almost 50 years, and the ban had been lifted for only the past four years. The few pictures I managed to find looked very inviting but, in my reading, I kept coming across fascinating descriptions of a unique indigenous nomadic people who live in this area—sea gypsies. Like characters out of “Water World,” they live out at sea on thatched-roofed boats up to ten months out of the year. They come in to land only during the monsoon season to wait out the harsh weather. That was all I needed to know to be hooked—mysterious people, enchanting, remote islands cut off from the tourist boom—it sounded perfect! I began making plans to paddle in the Mergui Archipelago.

It had been only a few short months ago that Myanmar was just a place I happened to notice on a globe. One of my favorite pastimes is poring over a globe and maps, searching out new places for adventure. One night, I happened to notice a cluster of islands off the coast of Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. The island grouping is called the Mergui Archipelago. My interest was piqued but, when I began researching the islands, there was little information to be found. The Burmese government had banned tourism for almost 50 years, and the ban had been lifted for only the past four years. The few pictures I managed to find looked very inviting but, in my reading, I kept coming across fascinating descriptions of a unique indigenous nomadic people who live in this area—sea gypsies. Like characters out of “Water World,” they live out at sea on thatched-roofed boats up to ten months out of the year. They come in to land only during the monsoon season to wait out the harsh weather. That was all I needed to know to be hooked—mysterious people, enchanting, remote islands cut off from the tourist boom—it sounded perfect! I began making plans to paddle in the Mergui Archipelago.

After partnering up with fellow photographer Jeremy Reyes and buying non-refundable airline tickets, our little-known destination made the cover of newspapers worldwide: Some Burmese students had attacked the Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok, Thailand, taking several hostages to negotiate their escape into the jungle. This left us with a major problem as we boarded the airplane for Phuket, Thailand: The border between Thailand and Myanmar was closed.

Our dreams of remote, untouched islands were quickly shattered. We figured that Thailand’s nearby Phi Phi islands and Phang Nga Bay would have to serve as our Plan B. Both were beautiful places that were easily accessible. When we talked with a local tour company, however, our hopes fell. He said that both places were tourist-saturated, with up to 300 kayaks a day. The next day, I whooped with joy when I saw the front page of a newspaper reporting that the Myanmar boarder had reopened.

Back on track with our original plan, we immediately moved into high gear and arranged a 30-minute boat ride across a narrow bay from Ranong, Thailand to the village of Kawthoung, Myanmar. As we neared the village, we could see old, three- to four-story cement buildings and storm-weathered wooden houses lining the beach. The surrounding hills were decorated with golden-roofed Buddhist temples. Dozens of long-tail boats buzzed about the docks, carrying fish and cargo in all directions.

Hefting our folding kayaks and gear, we made our way down the main street to the government offices. Although the 50-year ban on tourism had been lifted, the officials seemed cautious and wary of our intentions. We learned that Myanmar requires that government officials accompany all visitors to their country, both to keep an eye on you and to keep you out of trouble with the military. We explained our desire to travel and camp in the Mergui Archipelago, but we slowly realized that our desire to travel unescorted was hopeless. We dragged our gear down several blocks to a tour company. There, we learned that it had taken them five years of negotiating with the government to gain permission to camp on the islands. The company said that we could independently explore the archipelago as long as one of their guides accompanied us. With their assistance, we finally reached a satisfactory compromise with the government officials. Our guide, Aung Kyi, couldn’t have weighed more than 90 pounds. He had a bright, sunny smile and a seemingly endless supply of enthusiasm. We asked about his paddling experience, and he said that he and most of his Burmese countrymen were good paddlers, having mastered the art of paddling dugout canoes.

The last stretch of our long journey to reach the Mergui Archipelago was an overnight ride on one of the company’s boats. The sun set as we motored along. Soon the light faded, and lone fishing boats began to light up like scattered, bobbing lanterns in the blackness of the night. Civilization dimmed behind us, and the mysterious unknown loomed ahead.We motored through the night. At dawn, we anchored in a tiny bay in the Mergui Archipelago. As the stars faded and the morning’s light seeped over the horizon, the surrounding islands took form. Jagged peaks from dozens of islands rose high above the ocean’s surface, enclosing the waters of our anchorage. After lowering my kayak into the water, I paddled to shore. A pair of fresh leopard tracks in the sand meandered down a golden highway of beach, hemmed in on the left by a towering rainforest, and to the right by crashing waves. The tracks stopped at a creek and then disappeared into a swampy marsh. The beach ended abruptly at a rocky ledge with a cragged, rocky shoreline stretching onward from there. At the end of the beach was a sandy-bottomed cave. Inside, a few bats fluttered in the long shadows of early morning.

As I stood, contemplating the phantom leopard, I heard a strange singing noise coming from the high canopy. It sounded eerily human, although I quickly dismissed that as a possibility. It didn’t seem as if it could be made by a bird, either. Stranger, still, was that the song seemed to be a duet, with two distinct voices rising and falling with a slow, rhythmic tempo. As corny as it sounds, the melody sounded like a love song. I climbed a rocky ledge near the cave to try to get closer to the singing, but I couldn’t spot the singers, so I had to be content just to sit and listen to the beautiful and enchanting voices. The lyrical notes, lingering in the warm air, seemed to be in perfect harmony with the beauty and tranquility of my surroundings.

Later that morning, as we motored farther north into the islands, Aung Kyi told me that the mysterious singing had come from gibbons. Members of the monkey family, gibbons have long, almost spider-like arms and legs that enable them to spend their entire lives in the high rainforest canopy. Aung Kyi explained to me that gibbons mate for life, and they sing to establish their territory and strengthen their mating relationships.

As the boat droned northward, we kept a watch out for the floating thatched boats of the sea gypsies. Unfortunately, all that we came across were Burmese fishing boats. The sheer size of the Mergui Archipelago was beginning to overwhelm us. At over 300 miles long and more than 50 miles wide, and with more than 800 islands, we quickly realized that, despite having three weeks to explore, we were only going to see a tiny part of the whole archipelago. In order to see as much as possible, we decided to spend the first week covering long distances onboard the boat, and doing day paddles. We spent the next three days boating and paddling northward, deeper into the archipelago.

Our two inflatable kayaks could easily be used as singles or doubles, so Aung Kyi took turns paddling in the front of each of our boats. We especially appreciated the extra paddle strength in the heat of each day, when the scorching sun forced us to seek refuge under the towering trees that lined the beaches. In the dappled shade of the jungle, we dove into the cool, refreshing water to explore the undersea world.

Our two inflatable kayaks could easily be used as singles or doubles, so Aung Kyi took turns paddling in the front of each of our boats. We especially appreciated the extra paddle strength in the heat of each day, when the scorching sun forced us to seek refuge under the towering trees that lined the beaches. In the dappled shade of the jungle, we dove into the cool, refreshing water to explore the undersea world.

On December 1, the boat dropped us off on the northern part of Lampi Island to make a base camp. At over 20 miles long and five miles wide, Lampi Island is one of the archipelago’s larger islands. We would spend the next two weeks at this base camp, making day trips out in different directions.

The next morning Aung Kyi stayed in camp, assuring us that we would be all right for the day without him. Paddling around the northern tip of Lampi Island, the intensity of the sun and the humid air felt as if they were bearing down on us. Eager for a break, we donned our masks and fins and dove down and tied off our kayaks. The water was amazingly clear—we could see more than a hundred feet. Boulders covered the sea floor, along with blue and red branch corals; yellow and orange soft corals filled in the gaps, while schools of multi-colored fish hung like confetti, gently rising and falling with each swell that passed over them. A black-tipped reef shark rose to the surface near Jeremy, its fin slicing the water before it once again submerged into the depths. We entered an underwater forest of sharp rock pinnacles, and had to be careful not to get impaled on one in the waves. Purple-and-aqua-colored parrot fish grazed on the coral, and brightly spotted groupers took refuge in the reef’s dark holes and crevices. Jeremy flipped over a rock and cornered a spiny lobster the size of his forearm before letting it get away. Time escaped us, and when we finally made the dive to untie our kayaks, the tide had gone out.

We continued paddling, weaving between the hilly emerald islands. As we cruised along the shoreline of a small, unnamed island north of Lampi Island, I noticed something moving at the low-tide line. Maneuvering our kayaks closer, we saw that it was a large monkey. It didn’t see us as it climbed a rocky point and disappeared over the other side. Gaining momentum with a few hard paddle strokes, I let my kayak glide through a narrow opening in the rocks with Jeremy following. Suddenly, the monkey appeared within just a few feet of my kayak. I hadn’t expected such a close encounter, and neither did the monkey! Startled, he dropped the oyster he’d been eating, spun around, and bolted up the rocks toward the trees. Instantly, the surrounding rocks exploded with other retreating monkeys that I hadn’t noticed. An entire band of about ten adults and several more young took refuge in the nearby trees that overhung the beach. The treetops above us shook with the commotion. Aung Kyi told us later that these were macaque monkeys, which are numerous in this area. They come out in large groups at low tide to search for crabs and crustaceans. He said that their shy behavior can be attributed to their many enemies, namely crocodiles, leopards and tigers.

We made our way back to base camp, where we had dinner on the beach as the sun sank like a giant ball of fire into the dark ocean. In moments, the jungle at our backs began to come alive with strange sounds and the screeches of a legion of insects. Jeremy and I realized that we were on the opposite schedule of the surrounding rainforest: We were trying to go to sleep, while all around us the forest creatures were rising from their slumber to go about their nightly routines. We slept fitfully as the cacophany continued throughout the night.

With the sunrise, all of the noises vanished. In the early light of morning, the only evidence left from the night creatures’ wanderings were their tracks left on the sandy beach, and along the muddy edge of a river that ran near our camp. We found tracks of the hunter and the hunted: A lone set of large cat tracks trailed tracks from a band of monkeys. Tail marks from several monitor lizards meandered along the sand, and hoof marks with divots showed where a herd of wild boar had used their snouts to rut in the sand. At the other end of the spectrum, tiny paw prints left by mouse deer skittered about the sandy bank. Farther up the beach, on the riverbank, we found a huge dug-up area that Aung Kyi said was likely the work of wild elephants. Each mark told a small part of a larger story that had unfolded in the night while we slept.

As we ventured a short way into the jungle, the gibbons reminded us of their unseen presence with an early morning serenade. Long strands of black hair ripped from the coat of a passing Asiatic black bear hung from a thorny vine; a nearby tree sported deep scratch marks from a bear or tiger. We headed back to camp, unnerved at realizing that we were surrounded by wild animals that were hidden in the thickness of the jungle. As we ate breakfast, it struck us as ironic that the most mysterious of all the islands’ unseen inhabitants were the sea gypsies. Despite our searching for them, their watery world had shown us no evidence of their existence.

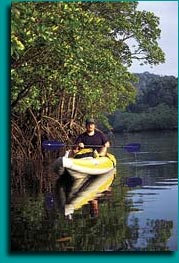

After breakfast, we launched our kayaks and paddled south. Aung Kyi rode in the front of Jeremy’s kayak. After about an hour of paddling, we came to a river. Rows of squatty mangrove trees hunkered over both sides of the river, giving the appearance of a gate. Paddling upstream, we were pleasantly surprised to find that it wasn’t very swamp-like. While the water in mangrove swamps is typically muddy, this water was clear, and the vegetation was spread out, making for easy paddling.

Even though the environs didn’t suggest a need for caution, we were well aware that we were paddling in the habitat of Indo-Pacific crocodiles, also known as sea crocodiles. The largest reptiles in the world, sea crocodiles reach lengths of up to 25 feet. They are responsible for over a thousand deaths in the waters of Southeast Asia each year. We were quiet as we paddled deeper into the swamp, suspiciously scanning our surroundings for danger. Every piece of driftwood, log, stump or other swamp debris seemed to perfectly resemble the shape of various parts of crocodiles. As we wove our way through the maze of mangrove trees, we became a little less jumpy. We were grateful for the lack of mosquitoes.

After a couple of miles, the mangroves gave way to towering walls of rainforest on either side of us. The treetops ahead began to shake. We paddled closer, looking for monkeys, and found a pair of great hornbills searching the high limbs for fruit. The black-and-white birds were the size of turkeys, but they had long, goose-like necks, and massive yellow beaks. Several brightly colored green-and-blue bee-eaters swarmed around the limbs of a dead tree standing at the water’s edge, and a flock of peculiar parrots with black bodies and red heads moved upriver along the canopy. White-bellied sea eagles surveyed us as we paddled underneath their high perches; one dove directly in front of us and snatched a fish out of the river with its large talons, then flew back up to its perch with its catch.

It was nice, for a change, to be on flat water without the constant motion of ocean swells. The current grew swifter and the vegetation thicker as we continued pushing upstream until our path became a narrow, winding tunnel of vegetation. We were hemmed in on either side by an intricate web of mangrove roots. Dense walls of branches and leaves compressed us, while larger tree branches tangled with vines made up a ceiling. A three-and-a-half-foot tree monitor lizard ran down the trunk of a leaning tree and splashed beneath the water’s surface only a few feet away. Like reflections of a rainbow, a cloud of multi-colored butterflies flew through the air over the river. Ruddering our 18-foot kayaks through the narrowing passageway had become nearly impossible when we emerged at the end of the river. A creek came splashing its way down from the mountains, forming deep holes filled with clear water. Jeremy and I hopped out of our kayaks to enjoy the water’s cool refreshment. I was floating, lost in thought about the idyllic setting, when Jeremy yelled, “LEECHES!”

Horrified, I dove into my kayak as Jeremy dove into his. A half-dozen slimy black three- to four-inch-long leeches attached to my legs were convulsing and growing as they drank my blood. I hastily ripped them off. Jeremy’s legs were also covered with the disgusting freeloaders. Once we were free of them, they left behind tiny bites that bled profusely. Aung Kyi told us that leeches inject their victims with a serum that thins the blood so that they can drink it more easily. We gave him a hard time about not having informed us of the possibility before our dip in the leech-infested pool.

While paddling back downstream, Aung Kyi spotted a 15-foot reticulated python. Its brown body slithered across the surface of the water with its head raised in search of a victim. This one was small in comparison to some reticulated pythons, which are the largest snakes in the world, sometimes exceeding lengths of over 30 feet.

Paddling back toward the beach, we left the jungle behind as we entered the maze of mangroves. I donned my snorkeling gear and flipped backwards into the cool water. Rows of mangrove root systems marched across a white, sandy bottom just five feet beneath the surface. A cloud of silver minnows hovering around the roots bravely ventured out in the safety of numbers to investigate my presence. Small stingrays glided effortlessly across the sand. Even in the serenity of this underwater scene, the sunken logs surrounding me looked enough like crocodiles to constantly remind me of where I was.

After our swim, we dried off in the sun and let the outgoing tide slowly suck us out of the swamp. Ahead of us, a resplendent ruddy kingfisher sat on a limb hunting minnows. Its wings and head were rust-colored with a tinge of violet, and its bill was a deep crimson. Its breast was a bright ginger, and its rump was splashed with a bluish-white patch. For several minutes it fluttered from branch to branch as our drifting kayaks kept pushing it farther ahead of us.

The sun faded, painting the surface of the water with an orange tint. A hundred feet in front of us, I noticed a dark object moving through the water, producing a “V”-shaped ripple in its wake. Sitting up for a better look, I saw a six-foot crocodile meandering across the swamp. So much for leisurely drifting; it was time to paddle back to camp!

While our base camp was the only legal place that we could stay onshore overnight, there were plenty of islands, sea caves, mangroves and reefs in the nearby area to keep us busy exploring. Each day held something new and different, but it wasn’t until the morning of December 10, after more than two weeks in the archipelago, that we found our first evidence of sea gypsies.

As Jeremy and I were taking a stroll down the beach, exploring the debris washed up by the morning high tide, we found an empty turtle shell with the head still attached. Aung Kyi told us that the sea gypsies use the turtle shell as a natural pot to cook the turtle meat over fires that they make in their boats. Our hope of finding these elusive peoples was renewed.

Two days later, we were six miles west of our camp, paddling past a couple of islands called the Nine Pins. The islands’ shorelines were riddled with two-story-high entrances to sea caves. While the openings tempted us to explore, rising swells smashing into their ceilings echoed warnings for us to keep our distance.

While paddling out from one of the island’s beaches, I noticed a fishing boat ahead of Jeremy and Aung Kyi. The engine on the 45-foot wooden boat was screaming at full power as it seemed to be making a run for shore. The stressed-motor sound drowned out suddenly as the bow rose skyward like a miniature Titanic, and the boat’s crew spilled out into the sea. Stunned, we watched the boat sink until only the tip of the bow remained above water.

A nearby fishing boat motored over and collected all but two of the eight-person crew from the water. The remaining two crewmen climbed up onto the wreckage. The rescue boat threw them a line, which they tied off to the bow. The rescue boat towed the wreck as close to shore as possible, until the sunken stern hit bottom. We paddled over to help the two exhausted crewmen who were still clinging to the wreckage. As we approached, they dove underwater in an attempt to salvage some of the boat’s cargo. They surfaced and dove several times, until they were out of breath. Without masks, their attempts at salvage dives were fruitless. Aung Kyi watched the kayaks while Jeremy and I put on our snorkeling gear to help out.

A nearby fishing boat motored over and collected all but two of the eight-person crew from the water. The remaining two crewmen climbed up onto the wreckage. The rescue boat threw them a line, which they tied off to the bow. The rescue boat towed the wreck as close to shore as possible, until the sunken stern hit bottom. We paddled over to help the two exhausted crewmen who were still clinging to the wreckage. As we approached, they dove underwater in an attempt to salvage some of the boat’s cargo. They surfaced and dove several times, until they were out of breath. Without masks, their attempts at salvage dives were fruitless. Aung Kyi watched the kayaks while Jeremy and I put on our snorkeling gear to help out.

The scene below was eerie, as I dove down the 40-foot length of the boat that had just minutes before entered its watery grave. Nets fanned out from the now vertical deck like ghostly hands, spreading out and closing back up as each wave pushed against the bow. The outline of the boat grew darker and creepier the deeper I swam. Fuel and oil from the engine room shadowed the reef below like a dark, viscous cloud. Deep in the shadows of the ship’s hull, the whitish forms of dead fish, the day’s catch, floated aimlessly about the wooden interior. The sight of the dead fish added to my growing feeling of discomfort. It seemed likely that sharks would soon be on their way. A mournful screeching noise filled the water as the tide slowly dragged the stern over the top of the reef. As I made my way up along the creaking panels of boards to the surface, waving nets threatened my escape, forcing me to dodge and maneuver around them. A few light bulbs were all we could find to salvage and, after several more dives, we gave the men a ride in to the nearby beach.

Although none of the fishermen spoke English, we were able to gather from their gestures that they had run aground on a reef and ripped a hole in the bottom of their boat. Figuring that they would get a ride with the two boats that had helped them and were still anchored in the small bay, we bid them farewell and paddled off.

Three days later, we were hanging out at our base camp when an odd object started floating toward us from the open sea. The shadowy form appeared to be constantly changing shape. As it grew closer, we were able to make out the silhouette of a group of men paddling on something that was too low in the water to see. We waded out into the breakers to help the eight men beach what turned out to be a makeshift raft. When the ragged men scrambled up onto the beach, we immediately recognized them as the crew of the boat that we had witnessed sink three days earlier. As if things weren’t bad enough for these shipwreck victims, it started to rain, drenching their clothes. We led them to a nearby cave to help them get a fire started so they could dry out. As we entered, the ceiling of the cave exploded with the wing beats of thousands of horseshoe bats. Once the fire got going enough to light up our surroundings, Aung Kyi pointed out the white shape of a six-foot cave racer snake curled in a crevice above us. He assured us that these snakes are not poisonous, and live almost exclusively on bats; we weren’t very relieved.

We cooked some rice for the stranded men and helped them get as comfortable as possible. The next day, we paddled Aung Kyi to a protected bay where fishing boats anchor each afternoon. There he arranged a ride for our shipwrecked friends back to Kawthoung, some 50 miles to the south.

Two days later, late in the afternoon of December 17, we were paddling south along Lampi Island when we spotted a seven-foot giant water monitor lizard scavenging along the low-tide line. It waddled its dinosaur-like body on short, stout legs, dragging its massive tail behind it. In the lizard family, only the Komodo dragons are larger. Although we were no threat to the creature, once it sensed our presence, it made a remarkably fast retreat into the cover of rainforest. As we continued our paddle, we came across three large bands of monkeys that were also taking advantage of the low tide, but it was what we found around the next point that we had long been anticipating.

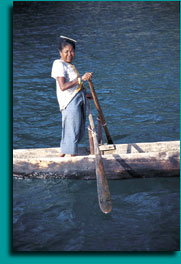

As we rounded a rocky shoal, the distinct shape of the thatched roof of a hut came into view, rising and falling in the deep blue swells. Beyond the floating hut was a shallow reef where a half-dozen dugout canoes of various sizes were being paddled by women. We knew at once that we had finally stumbled upon a band of sea gypsies. These people live like no others on earth. They don’t plant coconut trees or grow greens in gardens on land and, amazingly, they don’t fish. They are harvesters, living afloat over their “gardens,” where each day they wait patiently to be lowered to their food sources of crustaceans and other sea creatures that are exposed by the outgoing tide. We had happened upon them just as they were beginning to harvest the day’s catch.

As we rounded a rocky shoal, the distinct shape of the thatched roof of a hut came into view, rising and falling in the deep blue swells. Beyond the floating hut was a shallow reef where a half-dozen dugout canoes of various sizes were being paddled by women. We knew at once that we had finally stumbled upon a band of sea gypsies. These people live like no others on earth. They don’t plant coconut trees or grow greens in gardens on land and, amazingly, they don’t fish. They are harvesters, living afloat over their “gardens,” where each day they wait patiently to be lowered to their food sources of crustaceans and other sea creatures that are exposed by the outgoing tide. We had happened upon them just as they were beginning to harvest the day’s catch.

We watched from our kayaks as the women worked feverishly, each with her own task, to take full advantage of the narrow window of opportunity with the sinking tide. We paddled closer to a group of gatherers and asked Aung Kyi to greet them for us. The women answered Aung Kyi’s questions with single words or a head nod, and acknowledged Jeremy and I with several quick glances and a few shy smiles as they went about their work.

An older woman with a weathered face stood with graceful balance in the middle of one of the dugouts as three young women crouched at the front of the craft. When the elder put her weight into the oars crisscrossed in front of her, the canoe glided quickly across the surface. Lifting the carved paddle blades free from the water, she leaned back, setting up for another push. She paddled through the swells to within a few feet of the top of a boulder exposed by the tide, where the three younger women scampered out onto the rock. There, they began striking the mass of rock oysters with stones and collecting the tiny portions of meat into baskets with astonishing speed and efficiency.

a few feet of the top of a boulder exposed by the tide, where the three younger women scampered out onto the rock. There, they began striking the mass of rock oysters with stones and collecting the tiny portions of meat into baskets with astonishing speed and efficiency.

Nearby, a man’s legs sprang up into the air as he disappeared beneath the surface. He remained underwater for so long that if Jeremy or I had done so, it would have drowned us twice over. The woman who stood at the oars of their canoe looked unconcerned. After what had to be over four minutes, he finally emerged from the deeper regions of their “garden” with a couple of sea cucumbers stuck to the end of a bamboo spear. As the crabs, oysters, sea cucumbers, sea worms and other food stuffs were collected, the dugouts began to make runs to the main boat for unloading. Smoke rose from the thatched roof of the boat, where several women and children were busy cooking the harvested food over a fire. The man at the stern kept a close watch over where the boat was drifting along the rocky shoreline.

We observed the families for a couple of hours. Finally, with the setting sun and rising tide, activities slowed. Some of the couples stayed aboard their dugouts to eat their portion of the meal given to them by the cooks on the main boat. We paddled up to the main boat. With the day’s work done, the sea gypsies finally took the time to contemplate the two fascinated kayakers and their guide. Aung Kyi tried to speak with one of the men who knew some Burmese. Their mannerisms were reserved and shy. They didn’t ask us questions, like Burmese fishermen had done when we stopped for a visit earlier in our trip. They answered our questions in as few words as possible. “Where are you going?” we asked. “Wherever,” was the man’s reply. As I gazed into the weathered faces of these sea wanderers, I sensed a lifetime of experience that made me feel like a greenhorn. In their presence, everything seemed turned around—as though the water was really the land and the land was really the water. For them, the water is their home, while the land is just a place to explore from time to time. With so much of our world covered by water, maybe they have it right. For them it is a “water world”—they hold secrets about the sea that the rest of us will never know.

After our encounter with the sea gypsies, the islands and reefs that surrounded us took on a new feel.

For us, it was a place to enjoy for only a short time more, and that time was quickly coming to an end. On December 18, the boat that we had arranged for picked us up at camp and motored us back to Kawthoung, where we said a sad goodbye to Aung Kyi. As we boarded the longtail boat that would take us across the border back to Thailand, we waved to him. He folded his hands in front of his always smiling face and made several bows. His form grew smaller as we raced out to sea.

All too soon we were back in the chaos of streets lined with tour companies and hagglers, back to a place where the true personalities of people lay hidden behind an aggressive pursuit to make money. In our last four days at Patong Beach on Phuket Island, while we waited for our flight, it became obvious to me that the seemingly unchanging solitude of the Mergui Archipelago is in grave danger. Until now, it has remained mostly untouched, but at the alarming rate at which tourism spreads, now that the borders have opened, my advice to those interested in visiting these isolated islands is to go now—for change is at their doorstep.