According to my first-aid manual, I could afford to lose about five liters of blood before my blood pressure bottomed out, the shutters came down and I lost consciousness. I’d already lost quite a bit, so I did a few hurried calculations: If a thousand sand-fly bites sucked up a milliliter of my blood, after five million sand-fly bites, I’d be history.

Only five million! Considering I had about ten thousand flying around me right at that moment, it occurred to me that not just my sanity, but my very life, was only as secure as my defenses against these nasty little blackflies. Not that I really felt endangered. With only my hands exposed, I was just impressed that Mother Nature could deliver shock and awe in such small packages. Impressed and annoyed, but mostly itchy. That’s the trouble with fine weather in Fiordland—the sand flies love it too. They especially love fine weather at dusk, in damp, cool tidal creek beds where there is no wind, and Lumaluma Creek, at the head of Fiordland’s Edwardson Sound, in late summer is just that—sand-fly paradise.

Not that I really felt endangered. With only my hands exposed, I was just impressed that Mother Nature could deliver shock and awe in such small packages. Impressed and annoyed, but mostly itchy. That’s the trouble with fine weather in Fiordland—the sand flies love it too. They especially love fine weather at dusk, in damp, cool tidal creek beds where there is no wind, and Lumaluma Creek, at the head of Fiordland’s Edwardson Sound, in late summer is just that—sand-fly paradise.

Like most rivers in the southwest corner of New Zealand’s South Island, Lumaluma Creek runs dark brown with tannins leached from the soil by the extravagant rainfall. Just beyond its banks, small flat areas are mostly waterlogged and dotted with stumpy crown ferns.

From our kayaks, it looked like you could pitch a tent anywhere, but closer inspection revealed the soggy truth. The lower reaches of the creek are tidal, and with the tide out, the small, rounded boulders along the shore reveal their cloak of slippery algae that confine your feet to the awkward clefts between them when carrying a laden kayak.

The late afternoon sun lit up the far hills through the canopy of beech trees, but our campsite had lost any sunlight it had been blessed with hours ago. Soon enough we had set up camp, and the place started to feel like home rather than a damp, sunless gully.

Unfortunately, it was just as good a home for clouds of tiny biting flies, and they welcomed us with the same enthusiasm that they have shown visitors for hundreds of years:

…nor in short did we see any living thing on shore except birds and a small sand fly, but this annoy’d us more than perhaps fifty animals would, for no sooner did we set our feet on shore than we were covered with these flys, and their sting is as painful as that of a Musquitto, and made us scratch as if he had got the itch; indeed one of my legs became so much swell’d by this means that I was forced to apply a poultice to it, and was lame for two or three days.—Captain George Vancouver of HMS Chatham. Dusky Bay, 1791.

Mesh bug veils are de rigueur in Fiordland, and Brent, Peter and Ian had retreated behind theirs with desperate haste, while Anthony walked in brisk circles, applying insect repellent recklessly to his bare face and hands. His torment was only slightly reduced, as the writhing sand flies now stuck to his skin and were almost as annoying as when they were biting.

It was my turn to cook, and as I tended the small stove on the gravel riverbed among the densest aggregation of sand flies, I admitted aloud that this was a stupid place to camp. There was no dissent from my companions, but I think I detected a glare or two, for I had chosen the campsite on account of its proximity to a lake we wanted to visit the next day.

It’s hard to imagine any human activity more suited to satisfying the sand flies’ blood lust than camping. Tasks that require staying in one place, such as cooking, are particularly challenging.

An unattended bite escalates in seconds from a tiny speck of sensitivity impossible to ignore to a maddening itch way out of proportion to the insects’ size. They show little aversion to insect repellent, but they die in your dinner. They crawl through your eyebrows, bite your eyelids and get tangled in your eyelashes.

Cooking dinner is a trial, and eating it is equally challenging. While cooking, you can wear a mesh veil and constantly wave your exposed hands around. But eating necessitates removing your veil and exposing your face and neck to the onslaught.

Cooking dinner is a trial, and eating it is equally challenging. While cooking, you can wear a mesh veil and constantly wave your exposed hands around. But eating necessitates removing your veil and exposing your face and neck to the onslaught.

You move about constantly—one hand holds your dinner while the other hand, clutching your spoon, is engaged in fending off hundreds of biting flies from your face and protecting the hand that holds your food.

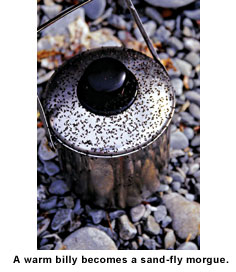

Meals are consumed in seconds, but not before they are garnished with tiny black corpses like coarsely ground pepper. Sand flies, steamed to death, float in your coffee. Too numerous to remove, they add a curious texture—like unfiltered grounds, but softer. After dinner, hands return to pockets and the incessant buzz of the little flies continues about your face until nightfall. Finally, after dark, you get some peace. The forest seems to sigh with relief, and the noises of the night—a distant kiwi or the melancholy call of the native owl (morepork)—seem more peaceful than usual after a day’s battle with the flies.

At daybreak, what sounds like rain on the tent is just the noise of hundreds of sand flies bouncing between the tent and the tent fly. They have homed in on your body heat and exhaled carbon dioxide, and they are hungry.

The only respite from sand flies on a calm day is when you put to sea. The last thing you do before pushing off from shore is rip off your long overtrousers and leap frantically into the cockpit to seal your spray skirt in a frenzy of activity, trying to simultaneously shoo them from your bare legs. Then you paddle like hell, pursued by a cloud of sand flies. You have to keep them airborne until they run out of energy. Paddle, paddle, flail, brush, paddle, paddle.…

When you get bitten—on your leg—under your spray skirt—you can only make a quick contortion to kill the beast beneath, then off comes the spray skirt—scratch, scratch, flail (don’t lose the paddle!), fumble to re-seal it, and paddle, paddle furiously again. This goes on for about 15 minutes. Where’s the wind when you want it?

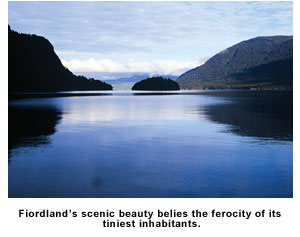

When the onslaught has finally subsided, and you no longer have flies buzzing about your ears and in front of your face, you can appreciate that Fiordland is not just a paradise for sand flies, but for sea kayakers too. That’s what keeps bringing my friends and me back to New Zealand’s southern fiords in spite of its endless hordes of insatiable sand flies.

Sand flies (Australosimulium spp.) have been tormenting people in Fiordland since its first inhabitants ventured there. As much as 800 years ago, feather cloaks and a layer of animal grease gave the early Maori some protection on their sealing forays into the region, but they never established a permanent presence there.

At the end of the 18th century, sealers slept in the same smoky caves that had been used by the Maori. Nineteenth-century mariners were among the first to record their impressions of Fiordland’s sand flies:

“The hold full of flies and the whole of us much distressed by them, they fasten on us with such fury and fly into the nose mouth and ears; the itching they leave is positively enough to drive one mad.”

—John Balleny, Captain of the Eliza Scott. Chalky Sound, 1839.

One hermit who lived for many years in Fiordland’s Milford Sound used to keep a 44-gallon drum by the front door of his hut. A small kerosene burner kept the drum as warm as a live body, and the outside of the drum was smeared with grease to trap the sand flies attracted to the warm surface.

Modern sand-fly defenses are both physical and chemical. Covering up is still the best method of protection. Uncovered skin can be liberally irrigated with DEET (diethyl toluamide). This stuff can melt plastic, so you don’t want any near your eyes. Sand flies know this, so they target your eyelids.

Contrary to common belief, DEET is not a repellent—it just inhibits biting. It works by blocking receptor sites in the sensory organs of biting insects so they cannot recognize you as a food source.

This, you understand, is no academic distinction. Even with liberal quantities of DEET on your hands, you’ll still have 30 or so insects crawling around on the back of each hand as you cook dinner.

They get stuck in a mire of DEET and sweat and crawl around among the hairs, dragging their sodden wings. You can squash them, but wiping the bodies away is not a good idea, as it thins the DEET film. So the carnage accumulates on the grisly battlefield of your skin.

Maori folklore has it that sand flies were created to ensure that the most beautiful of places, no matter how bountiful and benign, would still fall short of perfection. If that is so, then the creation of this annoying little biting blackfly is a triumph of economy. That such a small fly can have such a big impact on such a vast place is indeed a wonder.

On a calm day, if you come across a seal in a sheltered part of Fiordland, it’s unlikely to be reclining on the shore. Without a good breeze, sand flies dictate that Fiordland seals spend their daytime resting hours in the sea, slowly rotating at a pace that is just adequate to prevent sand flies biting.

This behavior can affect the seals’ energy budget and therefore their food requirements. The heat loss from spending more time in the water likely means that they have to eat more. Thus the sand flies have an impact on fish and squid populations far offshore. Little sods.

There is a theory that credits sand flies with making the kiwi and kakapo (a large endangered parrot) nocturnal, and after a few days paddling in Fiordland, anybody can see the sense in living in darkness.

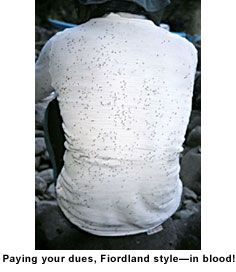

Sand flies, mosquitoes and other annoying insects are a part of wilderness travel there’s no  escaping. There is no bug-free option to be selected by ticking the box on a booking form. You pay your dues in blood when you visit Fiordland—it’s part of the deal. Just as you can’t experience a tropical rainforest without sitting out a wet-season thunderstorm, so it is with Fiord-land’s sand flies. They’re just as much part of our wilderness heritage as the pristine forest, the imposing mountains and the sheltered inlets. Our paddling paradise, too easily attained, would be devalued without them. And besides, as Maori legend suggests, paradise is intended only for the afterlife.

escaping. There is no bug-free option to be selected by ticking the box on a booking form. You pay your dues in blood when you visit Fiordland—it’s part of the deal. Just as you can’t experience a tropical rainforest without sitting out a wet-season thunderstorm, so it is with Fiord-land’s sand flies. They’re just as much part of our wilderness heritage as the pristine forest, the imposing mountains and the sheltered inlets. Our paddling paradise, too easily attained, would be devalued without them. And besides, as Maori legend suggests, paradise is intended only for the afterlife.

This was the argument I advanced to mitigate my earlier enthusiasm for our Lumaluma Creek campsite—an enthusiasm that had long since dissipated. About the only thing Brent, Peter, Ian and I agreed upon was that the sand flies were sure to protect our privacy, as most sensible people would stay well away from our campsite.

Sand flies are wilderness guardians of global significance. Captain Balleny thought so:

“I do not think either natives or settlers could live any great time in this part from the myriads of poisonous flies…” Without them, who knows what sordid development might have grown from the timber- and gold-mining townships of Cromarty and Te Oneroa, which now lie decaying beneath a carpet of moss in Preservation Inlet (Fiordland’s southernmost inlet). When the gold ran out, nobody stayed behind to raise their children in these towns.

Australosimulium spp. may have played a major role in preserving the land that now has World Heritage Site status. Humankind may have laid claim to a benevolent custodianship of Fiordland, but in truth, we have merely surrendered the land to a very, very small predator with a thirst for our blood. Not bad for a little fly.