I have been fascinated by Michipicoten Island ever since I became aware of it 43 years ago. The heavily forested island, located in the northeastern part of Lake Superior, is uninhabited by humans, seldom visited, and awash with wildlife, sandy beaches, rocky coastlines and jagged cliffs.

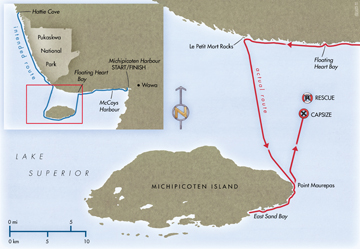

My partner, Judy, and I take a kayaking trip to Lake Superior every year. We usually go late in the summer to enjoy the cooler weather and fewer mosquitoes, but our 2010 trip began near the very end of August. We planned to visit Michipicoten Island and would begin our trip from Michipicoten First Nation land near Wawa, Ontario. The island itself is 15 miles long and 10 miles across. We’d cross to the island about 35 wilderness miles from the put-in.

I have been kayaking the Pukaskwa region of the Canadian north shore most summers for 24 years. I’ve made the full 110-mile trip from Hattie Cove to Michipicoten Harbour twice. Judy and I had made the nearly 10-mile crossing from Northern Ontario’s remote Pukaskwa region to Michipicoten Island for the first time the previous year. Despite my long-standing interest in the island, until our 2009 trip, time limitations, weather and caution regarding the unpredictable nature of Lake Superior had kept me from making the crossing.

The paddle out to the island had been a joy in fine weather and the return crossing had been even nicer; we’d only wished time had not constrained our explorations of the island. We had promised ourselves we would return.

Judy and I felt prepared for the 2010 trip. We were using a 21.5-foot Current Designs Libra XL, a tandem sea kayak I’ve had for 15 years. It has a great deal of cargo space and considerable seaworthiness. We added two deck mounts for sails that we would use if the winds were favorable. We dressed for immersion with 2-millimeter shorty wetsuits, which protect the body parts most vulnerable to heat loss—the body core, including the armpits and groin. Over the wetsuits we wore long-sleeve paddling jackets.

We also wore neoprene socks and neoprene sleeves on our forearms. I had deliberately chosen the shorty-style suits after hearing a Coast Guard medical doctor report on his studies of body-core heat loss in cold water. The study found that shorty wetsuits protect the shoulders and armpits better than farmer-john wetsuits. With neoprene on our lower arms and from our calves down, only our heads, elbows, knees and parts of our hands were exposed.

Our plan was to paddle from the put-in at Michipicoten Harbour to Floating Heart Bay, make the crossing to the island and explore its perimeter and larger streams. We would then cross back to the mainland, go 40 miles north to Hattie Cove, and paddle back to our starting point. If we had more bad weather days, we expected we would at least make it to Hattie Cove and shuttle overland back to our vehicle.

The previous year I’d felt vulnerable near the middle of this passage, so I purchased and registered an ACR Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) as a precaution. When activated, it sends a distress signal and location coordinates (via satellite and a rescue-coordination center) to the appropriate search-and-rescue team.

It was our security blanket not just for paddling but also for mishaps that might occur on land while far from a road, a telephone or maybe even another human being. At 63 years old, and with Judy not much younger, I felt the PLB was a prudent addition to our safety gear. The model we chose also allowed us send daily “OK” messages and our location coordinates to our loved ones.

We filed our trip plans using ACR’s web-based trip registration service. If we activated the PLB, the U.S. and Canadian Coast Guards and ACR would have key information available, including our intended route, the type, size and color of the kayak, and the colors of our paddling jackets. They would be able to keep our contacts apprised of our status until the rescue was complete. I keep the PLB tethered to my person so I can activate it even if I were separated from the kayak.

Our trip in 2010 was colder, windier and wetter than any prior year. The first two days were quite warm and the winds were moderate, but after the first stopover at McCoy’s Harbor, we spent three to five nights at almost every campsite awaiting a break in the weather. Lake Superior can be formidable, and most days we were confronted with 20- and 30-mile-per-hour winds.

After spending three nights at Floating Heart Bay (the closest approach to Michipicoten Island), we were presented with strong northeast winds and predictions of more of the same, so we decided to put off the crossing and instead proceeded westward, hugging the north shore for protection from the wind. The coastline here roughly parallels that of the island for the next 15 miles. We could cross from another point if the opportunity arose or continue to our turn-around point at Hattie Cove and catch the island on the return leg.

Our strategy worked fairly well until we got to Le Petit Mort Rocks in the afternoon. Here, the shoreline begins to arc gently northward to the west of Floating Heart Bay, and once beyond Le Petit Mort Rocks, the shoreline was no longer providing us adequate shelter from the northwest wind. After about an hour of being pummeled by wind and mounting seas, we decided to turn around and overnight in a cove, above a small beach behind the “little death rocks.”

Contrary to the earlier weather reports, the next day was fair and mild, with a light north wind. The latest weather reports indicated the northerly would last no more than a few hours, then change to the west. We saw this as our opportunity to cross, and we did, using our sails to speed our trip. Fortunately, the fair-weather window remained open long enough for us to make it to the island’s East End Lighthouse at Point Maurepas–but no longer. The wind shifted just before we arrived and the wind and waves rose suddenly right after we landed.

Once we were on the island, the unfavorable weather pattern returned. We spent two nights at the lighthouse then another mild day paddling around to East Sand Bay, a deep, southeast-facing scoop out of the island’s southern shore.

The fifth day opened with a gale from the southeast—a howling, sandstorm wind, alternating with cold, driven rain. Weather radio indicated conditions were more benign everywhere else. The gale lasted a full 24 hours, and then the wind turned to the west, and for the next two days we watched leaping waves march past the bay.

Judy and I reviewed our situation and our calendar. We were not making the progress we intended. Approaching the equinox, daylight was diminishing by several minutes each day, and temperatures, already below normal, were following suit. Nights were sometimes at or below freezing, and days were now typically around 50?F. We decided to head back to the mainland.

The next day, winds were fairly stiff, but from the west. By hugging the south shore as it arced northeastward, we felt conditions would be favorable for our return to the East End Lighthouse. The wind rose and shifted to the east that evening, and we spent the next day listening to the waves pound the rocks, periodically checking the kayak to make sure the waves weren’t reaching high enough to grab it from the boulder ridge where we had secured it.

The next morning, we admired a spectacular sunrise but decided to ignore the old mariner’s saying, “Red sky in morning….” The winds were gentle and from the southeast, and the weather report was for the wind to change to the southwest and increase to around 20 miles per hour in the midafternoon.

We could be across by then, and if we weren’t, we would be close to land and able to make safe harbor before the sea rose too high. We also took comfort from the fact that, in a worst-case scenario, we did have a personal locator beacon. So we packed up and shoved off. We decided to strike out to the northwest, with the wind directly at our backs, for Le Petit Mort, the same bay that we had departed the mainland from.

Within a half hour of our departure, the gentle southeast breeze had become a brisk southeast wind. Apparently the sequence of events was not to be a wind shift followed by a rise in wind speed. The wind speed was rising first. By then, however, the prospect of fighting the wind to get back to the island was daunting, and we figured that the southeasterly would help us get to the mainland before it changed direction.

Our reluctance to reverse course and return to the island was part of our undoing. Yes, it would be very difficult to fight the wind and waves if we turned around, but plowing into the waves, able to see the oncoming peaks, anticipate their effects and compensate accordingly would have afforded us much more directional stability.

A heavy following sea knocks the stern to the side, and since the top of a wave is flowing forward, the boat must be moving even faster than the water in the crest in order for the rudder to function. I became fatigued by constantly correcting for direction and compensating, after the fact, for wave impacts.

As we got farther from the island, occasional waves crossed from the southwest, even though the wind had not yet shifted. These were a nuisance, as they crossed the southeasterly waves at roughly a 60-degree angle, and where they met, the combined crests peaked while the troughs deepened. I expected we’d experience crossing waves for a short period of time after a wind shift, but the wind was still from the southeast.

As we would learn later, this herringbone pattern of waves, well known by experienced mariners and called the Witch’s Grin, is caused by a 90-degree shift in wind direction, and was accentuated by the waves from the south wrapping around the island and intersecting.

Then the wind changed—two or three hours before we expected it to—and grew stronger. Building southwesterly waves intersected the well-established southeasterly waves. We decided to change course to avoid being broadsided by the growing southwesterly waves and started steering a little east of due north, aiming for Floating Heart Bay.

Judy and I struggled to keep moving forward but we were getting knocked side to side. Where the two wave patterns converged, waves would occasionally toss a column of water into the air that appeared fully double the other wave heights.

Slowly, the mainland appeared closer, and the island more distant. We took some comfort when the GPS told us we were at least halfway. The wind was stronger than anticipated, and by now the waves seemed over six feet in height and the peaks higher yet. (We later learned the waves were up to 10 feet in height.) The shore disappeared from view about half the time.

I felt the stern swing violently to the left as we listed to the right. Almost at the same time, a large wave crest from the right washed over my shoulders, burying the aft half of the boat while the forward half seemed to pitch upward as it was thrown to the right. I felt the kayak roll into the curl of the wave and I knew there was no coming back. I shouted in outrage at the elements even as my mouth filled with water. And then I was upside down.

OK, we’ve all been taught that all you have to do is roll back up. Try that in a fully loaded tandem in heavy seas. Especially when you’ve never done it very well in a single, in practice. Nonetheless, I tried. The kayak barely rotated. I evacuated the cockpit and bobbed to the surface.

Judy was already out and hanging on. She asked if I was OK. I sputtered affirmatively and asked likewise. I didn’t notice the water temperature. With our two-piece shorty wetsuits, long water socks, paddling jackets and water shoes, we weren’t completely exposed, but I knew we couldn’t afford to stay in the water for long. We both had our paddles, which were attached by paddle leashes to our paddling jackets. We also were both wearing backpacks carrying hydration packs. These provided some insulation as well as flotation.

I decided the first order of business was to attempt self-rescue, so together we righted the kayak. I dispensed with the paddle-float approach and had Judy hold one side of the kayak while I pulled myself up from the opposite side onto the rear deck. The kayak promptly tipped over again. The second attempt worked better, and I reentered the cockpit.

The waves within the cockpit surged back and forth, causing an eerie water-clap sound like the back of a sea cave. I contemplated whether I should empty the cockpit with the bilge pump or have Judy get in first. A crashing wave suggested I’d never get the spray skirt on, much less be able to empty the cockpit in these seas. Then another wave sent me over, throwing me a good six feet from the boat.

My paddle was between my legs and one leg was wrapped in the leash. I had to get untangled before I could swim back to the kayak. By the time I had myself straightened out, the boat was 20 feet away. I was upwind of the kayak, and the wind was blowing it farther from me.

Judy was holding on to the lee side of the kayak, watching the bilge pump float away. For the first time ever, I had failed to secure the bilge pump tether to the kayak. Had Judy pursued it as it floated away we both could have been separated from the kayak. Waves were breaking over my head, and I swallowed some water.

We didn’t have a throw rope. I had always thought of it as something to assist another boat, and we always went alone. If Judy could have tossed one to me, letting it trail upwind of the drifting kayak, I could have reached it and pulled myself to the boat. We later learned that 15-meter throw lines are required boating equipment in Canada.

I tried to swim to the boat, but my tethered paddle was like a sea anchor. I reorganized myself and used the paddle to swim, albeit clumsily. Slowly, I approached the kayak, and I put on a burst of speed to catch up. I gained on it somewhat more quickly, but ran out of steam.

I had to catch my breath, but the crashing waves kept that from happening. By the time I recovered, the boat was 30 feet away. I tried again and again, without success. Judy watched me with a look of desperation.

At this point it was clear to me we were not going to self-rescue. I wasn’t even sure I was ever going to catch up with the boat. I fumbled and found the rip cord on the belt pack for my inflatable life vest. It promptly inflated but was so rigid that it was difficult to pull over my head.

It was clear we were going to need help if we were going to survive. I opened the pocket on my spray skirt and pulled out the PLB. I hated having to do this. I’d never before gotten myself into a situation I couldn’t get myself out of. But I had no other choice.

I unwrapped the antenna and uncovered the red emergency button. I pushed it. Two seconds. Did I hold it two seconds? I thought. Was my sense of time even close to accurate? The PLB’s display showed that it was sending coordinates, and its strobe began flashing. It would do this, presumably, for 48 hours.

I knew we wouldn’t last 48 hours in Lake Superior, so that would be long enough to either summon assistance or be a moot issue. I tucked it into my PFD where it was generally above the water and its GPS was well exposed. It was still tethered to my spray skirt so I wouldn’t lose it.

By now the kayak was a good 75 or more feet away from me. Judy appeared not to have inflated her vest yet. I began to paddle-swim toward her but that was awkward. I had never practiced swimming with my PFD inflated. I swallowed more water as waves crashed over me.

I tried different approaches, once even holding the paddle aloft like a sail, hoping the wind might move me toward her and the boat. It seemed they were receding ever farther, disappearing except when they bobbed up on top of a wave. Once I saw Judy had righted the boat, but then it was over again. Once more it was up, and she was in it. “Good girl!” I spluttered, aloud, but then it was over again. Why didn’t she inflate the life vest? Finally, I could see the vest inflated, but not on her. She appeared to have her arm looped through it.

I was starting to feel the cold. I didn’t know how long it had been. I looked at the distant shore and thought, “Is this how it ends? If help doesn’t arrive, this will be how it ends.” I looked for the kayak. I wasn’t even sure where to look anymore. I began to despair. I flashed on a scene from the film, The Perfect Storm, where the last surviving crewman from the submerged fishing boat bobs to the surface in his PFD and the camera pulls away, revealing the vastness of the sea—and how hopelessly lost he is in it. I chastened myself for being such a media creature that I would even think of such a thing in this situation.

Then I saw Judy and the kayak, so far away, Judy with that desperate, searching expression on her face, searching for me. I had been swimming in the wrong direction. Then I thought, “No, it will not end this way!” I resolved to make it to her side. The only way I could possibly catch her would be to paddle-swim as efficiently as possible, at a rate I could sustain for a long time. If I could travel just a bit faster than the kayak was drifting, I could catch it, if I could keep it up long enough.

I didn’t know how long it would take for rescue, if rescue was, in fact, on its way. If rescuers found me by homing in on the PLB and strobe I needed to stay close to Judy so she’d be found quickly. So I swam using the paddle. It was hard to estimate how long. Paddle, breathe. Paddle, breathe. Ignore the breakers. Swallow water. Breathe, paddle. It occurred to me that at least I wouldn’t get dehydrated.

I was closer. I could see Judy and the kayak more frequently. This was heartening. It seemed Judy was turning the kayak into the wind. “Good girl!” I thought again. “That will reduce the windage and help me catch up!” But then it was parallel to the waves again. At one point it appeared I was almost even with it with respect to the wind, but a hundred feet off to the side. I had to course correct.

As I drew nearer I saw that the front hatch cover was missing. The bow was riding low in the water. Judy must have accidentally dislodged the latches while attempting to right the kayak or board it. The lower profile of the bow may have been what was allowing me to catch up. What I didn’t know was that Judy was trying to scissor-stroke the kayak in my direction. Whatever was happening, I was finally getting closer. I was getting colder, and I was running out of energy. It must have been an hour by now that I had been chasing the kayak.

Just keep paddling. I had almost reached it before and had run out of steam. If that happened again, my energy was too depleted to make another attempt. I had to avoid the urge to put on a burst of speed. Just keep plugging. And I knew I must not grab for the kayak too soon; if I missed, if it lurched out of reach, I’d have lost momentum and have to reorient the paddle, and that might have the same result. I waited until I was in contact with the kayak to reach for it.

I caught the rudder deployment lines with my fingers. Judy came around the bow to the upwind side and called back to ask if I was OK and if I had activated the PLB. I gasped yes to both, but I needed to rest. The waves were crashing over my head as the kayak and I bobbed up and down.

I tried to use the kayak to elevate myself a bit in the water, my inflated life vest holding me somewhat away from the boat. I just hung there for a while, recovering. Once breath and strength returned, I worked my way around to the downwind side of the kayak and Judy did the same at her end. I moved along that side to join Judy at the bow. I asked her about her PFD.

“I can’t get it over my head!” she replied. “I can’t use both hands because I won’t let go of the kayak!” We had never before inflated our PFDs so we were inexperienced at actually getting them on, especially in a situation where one is in the water and does not want to release the boat.

I told her to hang on and I pulled it over her head. It had not been easy to get my own PFD over my head and it was harder to do that for Judy.

“I’m going to try to reenter the boat again,” I said. “Try to stabilize it from the upwind side—but don’t let it get away from you!” I worked my way back to the rear cockpit while Judy went around the bow. After a couple of tries, I managed to get into the boat. It felt terribly unstable. Judy tried to get in, and we capsized.

I reentered. We repeated the experience. The kayak just wasn’t stable enough for her to get in too. We were less than fully practiced in self-rescue. Our practices typically had taken place in gentle, warm waters and low winds using an empty kayak. Reentry of both kayakers in a flooded kayak having the stability of a half-soaked log was much more challenging.

In the process of entering and capsizing, my coiled paddle leash became tangled in the deck-mounted sail yoke. Both Judy and I had our paddle leashes get wrapped on the sail yokes. We had kept the yokes mounted because of the inconvenience of stowing and retrieving them as needed. Our coiled paddle leashes compounded the problem in that they persistently fouled on everything they encountered. Judy was never able to release her paddle. I got it loose for her by releasing the leash’s Velcro fastening.

Judy gave up on trying to get back into the boat and hooked her arm over the forward cockpit coaming and hung on. I tried to paddle, partly to maintain some stability, partly to generate some body heat, and partly to try, however incrementally, to move us toward the mainland shore still four or five miles to the north.

Judy’s drag on the port side of the boat kept turning us in that direction. Trying to overcome the drag using the rudder and paddling mostly on my left was only slightly effective. I know at least once we turned in a complete circle. Eventually, I was paddling just to be doing something.

The chill was beginning to penetrate. We both had lost our hats. I could feel the heat leaving my body in the 25-knot wind. I was in the kayak, only half immersed, but Judy was still in the water. It had seemed warmer in the water, but sensation can be deceptive. Survival was beginning to look less likely. I could keep believing we would survive as long as I was reasonably strong and our objective realistically attainable.

But it had become apparent that even if we were to make shore on our own, we would be too hypothermic to survive. And at the rate we were chilling, we would never make shore. We had been heartened when I had regained the kayak, but dismayed by our inability to get us both into the boat without capsizing. Our inability to make progress toward shore was just as discouraging.

Our only hope was that the Coast Guard had received our PLB signal, and that they were en route. We spoke of it circuitously. We told each other that we loved each other. Judy told me how she feared she had lost me. I told her of the wrenching minutes when I couldn’t see her or the boat. We kept hoping to see our rescuers and wondered how far they would have to travel. We didn’t know how much time had passed, but it seemed like hours.

I kept paddling. My arms hurt. My hands barely felt like a part of me, but they continued to follow my instructions and I held on to my paddle. The waves must have been getting more organized, with less of a southeasterly component, as I don’t think I could have stayed upright if the herringbone peaks had been prominent.

I was beginning to weaken significantly and feel the cold in my bones when I heard a deep drone. I saw a magnificent, huge, four-engine prop plane approaching us from the southeast, flying what seemed to be only a couple of hundred feet above the water.

It was the Canadian Coast Guard search plane. We would later learn it had come all the way from Trenton, Ontario—some 90 miles east of Toronto. The C-130 aircraft was a beautiful sight as it flew directly over us. It seemed like forever before it turned and circled. It seemed to be flying a pattern and only flew over us again after completing it, then circled some more.

We assumed it must be checking to be sure we weren’t the only ones out here. But it also soon became apparent this aircraft was not going to rescue us. It was the search half of search and rescue, and the faster half, at that. How far behind was the helicopter? We could only wait.

Time was elastic. The half hour it took for the U.S. Coast Guard helicopter to arrive seemed like well over an hour. It approached from the south, across Michipicoten Island, and pulled to a hover about 200 feet away. My arms were rubbery, barely able to brace the kayak against battering by the waves, and I hurt from chill and fatigue.

My field of vision had closed down to a tunnel, and I didn’t see the rescue swimmer leap from the helicopter. I looked over my right shoulder to see what looked like a finless dolphin slicing through the water at amazing speed toward us.

In a moment, the rescue swimmer reached me and said, “We’re going to get you both out of here. I’ll take your wife first and come back for you.” I would later learn his name was John. He then went to her, gave her the thumbs-up, said, “You’re going to be okay!” and told her the plan. He grabbed her by the loop on her backpack and towed her to the helicopter, placed her in the basket and sent her skyward. When he came back for me, he said we had a nice kayak and nice equipment.

I think I thanked him. At this point, I was only intermittently aware of things, as I was beginning to shut down, but when he said he was going to tip the kayak over so he could take me, I had enough presence of mind to reach behind my seat and grab the waterproof pouch tethered to it. It contained a credit card and ID, some money, and most importantly, the car key. I wasn’t capable of unclipping it, so as I fell out of the kayak, I just pulled until the cord snapped.

John told me to relax and let him do the work. He towed me through the water by my backpack strap at remarkable speed. The water felt so warm compared to the icy wind. He laid me on my back in the basket, which was submerged just below the waves, and told me to hold my glasses. As I rose through the air I turned my head to see my capsized kayak drifting slowly northward, presumably never to be seen again. I didn’t care.

The prop wash from the chopper blades was intense and freezing. Whatever body heat I had left seemed to get sucked out of me on that ascent. I was helped out of the basket by one of the crew, positioned on the floor in the back and given a blanket.

Judy was sitting in the one spare seat in the rear. We both expressed our relief at being reunited and for our rescue. Cramps set in my entire body, especially my neck. Mercifully, Judy didn’t experience any cramping. A crewman put a radio-equipped helmet on me so the crew and I could hear each other. He pulled off our PFDs and our water socks, and said the heater in the cabin was cranked all the way up. It was stifling for them but good for us. John turned off my PLB and said he would love to learn the whole story.

When we arrived at the Wawa airport, the ambulance was waiting. We were each asked whether we could walk to the ambulance. For me, there was no way that was going to happen. Judy was able to walk the few steps to the ambulance.

We had spent over three and a half hours fully or semi-immersed in the water. The Coast Guard reported the water temperature at 55° F. I was more hypothermic than Judy. The paramedics couldn’t get a temperature reading on me using a forehead scanner.

They immediately stripped all the wetsuits and gear from us and wrapped us in warm blankets. Once we were in the emergency room at Lady Dunn Hospital, they were able to take ear-probe temperatures. Mine was 93°F, and Judy’s temperature was 95°F. I was still cramping. They put us both under hot air blankets, and because my hypothermia was more severe, I was put into the trauma room and administered a warm-water IV, followed by warm liquids to drink. Judy recovered more quickly, and after three hours of treatment, we both enjoyed a hot shower.

I learned later that it would have been dangerous—possibly fatal—to have taken a hot shower early on. Warming the skin too rapidly can cause a sudden rush of cold extremity blood to move into the body core, causing cardiac arrhythmia. We were given wonderful care, receiving the almost undivided attention of a physician and the ER staff for four hours.

After we had both recovered sufficiently, the hospital staff provided us with warm clothing and summoned a pair of community volunteers from the Wawa Area Victim Assistance program to return us to our vehicle, which we had parked not far from the hospital. One of the volunteers, hearing our story, told us we had been caught in the “Witch’s Grin.”

Five days later, we were contacted by Dave Wells, a kayak outfitter in Michipicoten Harbour near Wawa. We had provided him, the police, local fishermen and anyone else we could think of with a list of the kayak’s contents in case any of it were to show up.

Dave told us that our kayak had been washed ashore on a sand beach adjacent to his facility. It had drifted 35 miles to one of the few patches of sand in a coast that is nearly all rocks.

Dave and his staff had emptied the kayak of sand, brought it to their facility, emptied the hatches and dried out the gear. The kayak was nearly undamaged. We lost my camera and some non-floating items that had been stored in the cockpits, but recovered almost all the rest. Even my paddle was retrieved by local folks who turned things over to the police or Dave. Our GPS was found on the beach, and it still works.

After the accident I wondered if having the PLB had influenced our decision to proceed even when we had doubts about the crossing. I know it went through my mind that morning, weighing the factors, that if conditions turned really rotten and we got into trouble, we always had the PLB to fall back on. Would we have proceeded without it?

I don’t know the answer, but I know I will be wary of allowing it to influence me in the future. No doubt our family and friends will demand we carry one on future excursions (as if we weren’t convinced ourselves) and after this event, I expect they will be tracking our movements and status carefully.

Surviving a near-death situation can be a life-altering experience. In our case, it has served to cement the bonds between Judy and myself. Seeing a loved one’s life at genuine risk, especially knowing you may be responsible, can be more frightening than being at risk yourself.

It reprioritizes your values in a hurry. Both of us are more aware of how precious we are to one another. The single strongest memory I have of that event is the image of Judy in the distance, clinging to the kayak as waves intermittently heaved her into view, her face filled more with concern for me than with fear for herself.

We two aging, far less than optimally conditioned sea kayakers, capsized in Lake Superior under adverse weather conditions and weren’t able to self-rescue, yet we survived thanks to a combination of technology and the extraordinary efforts of a team of people who have dedicated themselves to bailing the rest of us out of situations we should never have put ourselves into. Certainly, our experience underscores the importance of kayakers having a Personal Locator Beacon for any but the most protected waters.

The only consolation we perceive in consideration of the public resources expended to save us is the hope that our case contributed positively to the justification for the U.S. and Canadian Coast Guard budgets. We cannot fully express our gratitude.

Robert Beltran retired from EPA in 2007. He is a coauthor of The Great Lakes: An Environmental Atlas and Resource Book. He and his late wife kayaked Lake Superior annually from 1986 until she developed cancer in 1997. Bob resumed kayaking the lake with his new partner, Judy, in 2005.

Judith Gottlieb retired from Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources in 2009, where she was a wastewater engineer for the Milwaukee River Basin. She has been kayaking Lake Superior annually since Bob introduced her to the sport in 2005.

Lessons Learned

When analyzing most kayak accidents, one rarely has to look very far beyond a few common basic safety measures to see what went awry. The majority of mishaps typically involve hypothermia and one or more (too often all) of four basic errors.

Paddlers who got in trouble were 1) not wearing PFDs, 2) not dressed for immersion, 3) paddling a kayak without adequate flotation, and 4) had inadequate rescue training and practice for the type of trip attempted. There is often a bad decision to launch, followed by one or more unexpected waves and/or gusts of wind and, voilà—deep trouble.

In this story bad things happened to paddlers who thought they were fairly well prepared. Both Robert and Judy wore PFDs as well as wetsuits, and paddled a kayak that had demonstrated “considerable seaworthiness” to them for the past 15 years.

They also had several years’ experience in the area, and a personal locator beacon “as a last resort” to get them out of just about any trouble they could get themselves into. In spite of their feeling well prepared for the trip, trouble did come, and it came in spades.

While stories of survival can be inspiring—Bob and Judy’s determination after they found themselves in the water was no less than heroic—our goal is to avoid putting ourselves in circumstances where our survival is in jeopardy.

Back to Basics

Bob and Judy did wear PFDs, although the inflatable type they wore proved less than ideal when they ended up in the water. Although the PFDs ultimately did the job of keeping them afloat—despite the obvious operator error—standard PFDs that use foam for flotation would have caused them fewer problems, and the inherent insulating properties of foam would have kept them somewhat warmer.

Bob and Judy hadn’t practiced paddling, swimming and doing rescues with their PFDs fully inflated. Bob told me that they just didn’t think that practice seemed necessary. Making time to practice with the gear you will be using on a trip can help reveal any unexpected complications you might encounter.

While Bob and Judy had considered themselves dressed for immersion, they were not dressed for a capsize and wet exit in the middle of a 10-mile crossing in very rough conditions and in 55-degree water.

Full wetsuits designed for paddling, or even drysuits and neoprene hoods would have been better options. Had Bob and Judy both been warmer after Bob’s long swim back to the kayak, they both might have been better prepared, not just physically but mentally as well, to explore and execute a wider range of reentry alternatives, such as deploying their paddle float (more on this later), that might have gotten them both out of the water and back aboard the kayak.

No immersion wear can assure survival in cold water forever, but what’s more important than survival time is the time immersion wear provides for clear thinking, adequate strength and manual dexterity.

Most tandem kayaks are quite stable, especially when loaded with camping gear, but they can take on a lot of water after capsizing and lose much of their stability. With a hatch lost and the forward compartment flooded, Bob and Judy’s tandem was made even less stable.

Also, paddling a tandem kayak “solo,” that is, without another kayak to help out and provide stability for reentries and pumping, definitely limited their rescue options. Other gear issues, such as getting tangled in paddle leashes and not having a throw line, compounded their problems. (Given their luck with the paddle leashes, I don’t know if having another few dozen feet of throw line in the roiling water would have improved their situation much.)

The main lesson still left to learn before Judy and Bob attempt paddling solo in open water again—and the most important point, I believe, for readers to ponder—involves shifting our focus away from gear.

Focusing on things like tangled leashes and throw lines they wish they’d had and difficult PFDs is a bit off the mark (like “rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic,” I believe the saying goes).

Certainly a throw rope could have saved Bob from the epic swim, but then what? And life jackets that didn’t have to be awkwardly forced over their heads would have been much more helpful, for sure, yet still left them essentially in, or rather out of, the same boat—miles from shore without the skills to reenter their kayak, shivering and waiting for a helicopter ride to the hospital.

While the PLB certainly saved their lives, and their shorty wetsuits kept them alive long enough for the Coast Guard to save them, the fourth safety principle I listed above could have spared them the trauma and danger of requiring a rescue: Paddlers should have adequate self-rescue skills and practice for the trip planned.

Bob admits that they were “less than fully practiced in self-rescue.” Bob had done some rescue training in calm conditions and had even managed to roll an empty single in practice.

Judy’s only background involved having taken a basic canoe course as a teen. They had not practiced at all together nor practiced rescues in a tandem or in a loaded kayak. Most importantly, they hadn’t practiced in a loaded tandem together in conditions similar to those they could and did encounter on Lake Superior.

Bob mentions that rescue “practices typically had taken place in gentle, warm waters and low winds using an empty kayak.” Unfortunately, this is all too common an approach.

While protected areas are a great place to begin your rescue training, allowing you a safe place to learn, it takes more than flat-water practice to develop the sort of self-sufficiency that might actually keep you from having to activate your PLB. Once you feel confident with your technique in calm water, a good next step is to move to a safe place to practice in more challenging conditions; for example, off a wind-blown point where you’re being blown back into a calmer area.

After that, the third step might be to head back in to the calm area and practice in a loaded kayak, since it handles much differently than an empty one. While it might sound inconvenient to pack your kayak full of camping gear for a practice session, you might more easily simulate a load by filling jugs of water held in place by float bags.

You could also practice with an actual load of gear on the first day of a trip, in the shallows near shore as you’re coming into camp. You wouldn’t even have to get your head wet; just jump out in waist-deep water and tip your boat over to see what it takes to get back in.

Many paddlers I know resist this, because they say that they don’t want to get wet and cold. This would be a valuable reality check on whether or not their immersion gear is adequate for a capsize in actual conditions. If they aren’t eager to get in the water to practice, it’s a pretty good indication that they’re not properly dressed. The information you gather during an in-trip practice could provide you with invaluable information on how well you are equipped to carry out any crossing you may have planned in the days ahead.

If Judy and Bob had done such a practice session before even considering their initial crossing to the island, they likely would have discovered the same weaknesses in their gear and skill in a much less traumatic venue. Knowing that the weather was worse than usual, they might have reconsidered the crossing if they found any reason to be less assured about their current level of skill and the suitability of their gear.

The fourth step in preparation would be to practice in a loaded kayak out in rough conditions. Such a practice session would duplicate what Bob and Judy went through but without the dire consequences. Without a graduated series of practice sessions, the mid-crossing capsize they experienced was like learning to swim by jumping straight into the deep end of the pool.

By practicing before the cruise and the crossings they would have discovered that their inflatable PFDs were difficult to deploy, and they could either have had a chance to figure out a technique for getting them over their heads more easily or else decided to switch them out for foam-equipped vests.

They would have learned that their shorty wetsuits were perhaps a bit skimpy for immersion in 55-degree water and that they needed more thermal protection. And they might have prepared for the drill by making sure essential gear like the bilge pump was securely attached to the kayak.

They also would have discovered that the latches on their hatch covers were a problem. Fifteen years ago, when their double was made, the lever-and-slider systems for hatch cover straps were common and prone to release accidentally.

Manufacturers have since addressed this problem in a number of ways—bending the end of the levers upward, putting jogs in the sides of the lever arms, or putting webbing with snaps on the slider—all to help prevent accidental tripping. Unfortunately there are still hundreds of the old closure type still lurking on hatch covers, and they are susceptible to getting tripped, especially in reentries when people are crawling over the decks.

Regular practice would have revealed this problem and sent Judy and Bob to seek solutions. Ironically, as Bob pointed out, the flooded bow and the resulting change in the trim of the kayak may have been what made it possible to catch up with the kayak.

Bob’s leash was attached to his spray skirt, instead of his kayak, leading to his becoming tangled in it away from the kayak and precipitating his long swim. He and Judy found the coiled leashes they used were especially prone to tangles and snares.

Practice would have exposed the possible problems with their paddle leashes and left them better able to weigh the pros (such as not losing your paddle) with the cons (entanglement issues) and consider possible alternatives.

Most of all, taking the time to practice gives paddlers a more realistic idea of their reentry skills, allowing them to make better informed route decisions. Crossings require a higher level of expertise in rescue skills and knowledge of alternates. The greater the exposure, the higher the risk of bad conditions and need for practice in rough water.

My standard advice to students is not to paddle in waters that are rougher—or likely to get rougher—than they’ve practiced rescues in. To take this a step further, always add a set of conditions to your skills and equipment. Saying, “I’ve practiced paddle-float recoveries” won’t help you make decisions as well as it would to say, “I’ve done solo-reentries in three-foot seas and twenty-knot winds with a loaded kayak”. Similarly, an assessment like “I’m dressed for immersion” is not as useful as “I can still function well in my immersion wear after twenty minutes in fifty-degree water.”

A rescue is something that happens to paddlers who don’t yet have the skills to reenter their kayak after a capsize. Capsizing is in itself not the problem for kayakers. For those with a solid roll, it’s just a momentary dunking. It is when paddlers end up in the water without the proper gear or regularly practiced skills to reenter the kayak that a capsize can become life threatening.

The major lesson to be learned from this incident is what can happen if you take a set of skills and equipment that may be adequate for touring in calm, warm water along a friendly shoreline, and then attempt to pull off a significant open-water crossing during a fluke of a weather window on a large body of cold water with a nasty reputation.

Exposure is a key consideration. It makes a big difference whether you are paddling five minutes or five miles from the nearest safe landing zone. On longer crossings, you’re allowing more time for the conditions to change. Your decision to cross has to be based not on what conditions are like at the start, but on what they could become before you make a safe landfall and how much strength you’d have left to deal with adversity, say several hours after leaving shore.

Bob and Judy’s first crossing committed them to a second crossing, doubling their time of exposure. The brief weather window that allowed them to get to the island wasn’t forecast and was merely a break in a pattern of unfavorable conditions. They would need a second break in the weather to get back to the mainland. While I agree with their assessment that making the crossing back to the mainland was a poor decision, making the crossing out to the island in the first place set them up for trouble.

Once they ended up in the water, Bob mentions having a paddle float, but decided not to use it for his reentry because Judy could stabilize the kayak for him while he got in. That strategy ended up being a good way for Bob to get himself out of the icy water, but while Judy provided the stability to allow Bob to get back in his cockpit, he was not able to brace well enough in the conditions for her to get back in without re-capsizing them. Using a paddle float can provide much more stability than braces alone. Better yet, if both paddlers have paddle floats, especially ones that they’ve practiced with previously, it can provide enough stability on either side of the kayak to help counteract the effects of confused sea conditions, such as those encountered by Bob and Judy.

Even with a pair of paddle floats deployed, there might not have been enough stability to remain upright in the teeth of the Witch’s Grin, given some of the inherent issues with rescuing tandem kayaks. Although they are usually perceived as being a safer, more stable craft than single kayaks, after a capsize tandems pose several problems. Their decks are generally higher and can make reentry more challenging than it is with single kayaks. The reentry sequence needs to be coordinated between the two paddlers. The large cockpits allow for the entry of lots of water and for lots of sloshing (free surface) that creates instability. Bob was able to get back in the kayak for good once they drifted into the somewhat less confused seas beyond the Witch’s Grin, and it is quite likely that paddle floats would have worked to get Judy aboard and kept the double upright, especially if the two had done a little rough-water practice beforehand.

While investing in a PLB is a good idea, investing in some rescue classes, as well as some time practicing before heading out is an even better idea because the training can help you avoid the trauma of having to deploy a PLB. Having some expert guidance can provide an invaluable source of advice and perspective, and nothing but actual practice—especially in at least some moderately rough seas—can reveal weaknesses in your gear or skills that might land you in trouble.

Practice your reentry skills regularly, at least every paddling season. Before every trip, ask yourself when was the last time you and your regular paddling partner practiced reentries? And did you practice together, in the same boats and conditions you are likely to capsize in? Reentry skills are perishable. When was the last time you checked the “expiration date” on yours?