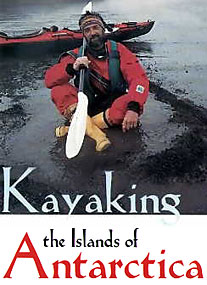

When my Danish friend Olaf Malver rang me up and asked me if I wanted to join a select group of paddlers going to Antarctica for an exploratory sea kayaking trip, I ran to pack my cold-weather paddling gear.

When my Danish friend Olaf Malver rang me up and asked me if I wanted to join a select group of paddlers going to Antarctica for an exploratory sea kayaking trip, I ran to pack my cold-weather paddling gear.

Olaf personifies the spirit of his Viking ancestors, having climbed over 200 mountains on three continents. In recent years he has turned to sea kayaking, with a special passion for leading trips to remote regions and extreme climates.

Any paddling adventure with him was bound to be fun. It had long been a dream of mine to explore the islands and the Southern Ocean surrounding the continent of Antarctica, yet the time, expense and logistical problems involved in reaching this remote wilderness had made this dream unreachable.

Where there were previously few options for transportation to Antarctica, the situation has now changed. With the end of the Cold War, many highly specialized resources have become available for scientific expeditions and adventure travel.

For example, the MS Academik Shuleykin, a 235-foot Russian research vessel with a hull strengthened for ice and an Arctic-seasoned crew, recently appeared in Argentinian waters and began offering its services to eco-travelers and research teams wishing to travel to Antarctica. This ship would provide the passage for our group to this previously nearly inaccessible landscape.

In January 1998, the midpoint of the austral summer, I joined a half-dozen paddling friends of Olaf in Ushuaia, Argentina, the southernmost city in the world. Jonathan Calvert came from Texas, Larry Rice from Illinois, Dana Isherwood, Lou Gibbs, Phil Rasori and I came from northern California, and Olaf’s old friend Jan Jantzen flew in from Copenhagen. Stowing our folding boats onboard the Russian ship, we set off down the rain-swept Beagle Channel, bound for Antarctica.

That night we entered Drakes Passage, long regarded by mariners as one of the most dangerous places in the world to sail a boat.

But in the steel-hulled Shuleykin, equipped with powerful twin engines and modern navigational equipment, we felt safe. We set a course toward South Georgia Island, 1125 nautical miles to the southeast.

We soon discovered that the stories we had all heard about this Southern Ocean were not exaggerated. These seas seemed charged with conditions more immense, more powerful than those through which any of us had ever drawn a kayak paddle.

We soon discovered that the stories we had all heard about this Southern Ocean were not exaggerated. These seas seemed charged with conditions more immense, more powerful than those through which any of us had ever drawn a kayak paddle.

Only here, between 50 and 60 degrees south latitude, does a continuous band of open water encircle the earth. Vast tropical seas stand face-to-face with the frigid polar ice, unrestrained by any land mass. To further intensify the situation, these winds and currents become constricted as they squeeze between the southern tip of South America and the north-thrusting Antarctic Peninsula.

The next morning I emerged on deck and gazed out over the tempestuous vista that surrounded us. A seemingly endless succession of ocean waves, some four or five stories high, raced along with us in an easterly direction. I wondered how the Shuleykin would handle these gigantic waves when it was time for us to return west and face the onslaught head-on.

The scene conjured up memories of rapids on a white-water river, on an oceanic scale. The words of explorer Robert Meithe came to mind, who once observed, “Cape Horn is the place where the devil made the biggest mess he could.”

For three and a half days and nights we surged along at 12 knots, the powerful wind, waves and currents at our backs. For those of us who were heading to Antarctica for the first time, the ocean around us seemed vast and utterly wild. From my favorite vantage deck at the bow, I gazed out over the ever-changing panorama of seething seas and sky for hours.

In the evenings I would go down to the lecture room on the second deck to learn more about this fascinating world from lectures and slide shows that the American and European naturalists and historians onboard presented. There was also an extraordinary series of videos, Life in the Freezer, that the British had produced about Antarctica.

Up on the bridge deck there was a library stuffed with books about natural history and the exploration of the area. When I could absorb no more information, there was a sauna back down on deck two that the crew kept super-heated, hotter than any sauna I had ever known.

There the Russians introduced me to their custom of rubbing honey on their perspiring bodies, claiming that it was great for the skin.

At about 54 S, we began to sense a drop in the air temperature, a sign that we were crossing the Antarctic Convergence. The naturalists explained that this is a region where deep currents from the north collide with frigid, denser polar ones, forcing the nutrient-laden waters to the surface.

The variety and concentration of aquatic and air-borne wildlife confirmed that we had entered one of the richest feeding grounds in the world. Pelagic birds, some of which I had never seen in the northern hemisphere, were much in evidence here: pintados, prions, southern giant petrels and royal albatrosses with a wingspan of up to 12 feet.

Three hundred sixty million birds of 20 to 30 species are estimated to migrate through or live fulltime in Antarctica, including six species of albatross and countless flocks of agile, swift-moving penguins.

The penguins displayed remarkable teamwork as they darted, dove and leapt along the surface of the sea in pursuit of prey. We also spotted fin and humpbacked whales, seagoing fur seals and pods of orcas and bottlenose dolphins that had come to join the feeding frenzy.

Paul Konrad, an editor from Wildbird magazine who was also a passenger on the Shuleykin, explained how the whales and dolphins came here to feed on the immense quantities of krill that swarmed invisibly through the water around us.

The day before we were due to arrive at South Georgia Island, Olaf announced, “It’s time to put our boats together!” But a 20-knot, near-freezing wind was whistling outside, so we tried assembling the first of our three folding kayaks inside the ship’s bar. Alas, the big doubles proved much too long for that cozy sanctuary.

We moved out onto the wind-swept deck, clutching the various pieces of our craft tightly to prevent them from being blown overboard. The ship had slowed down now, and big waves were rolling up and overtaking us from astern.

A Russian crewman cautioned us always to keep a firm grip on a guardrail whenever we moved near the edge of the rolling, pitching deck. A glance at the seething sea racing past and no one required a second warning. The aluminum pieces of the boat frames were a struggle to fit together with our numb fingers, but by nightfall our three kayaks, as well as a unique collapsible white-water canoe of Norwegian design that photojournalist Larry Rice had brought along, were all lashed down securely on the aft deck, ready for launching.

Later that night, I visited the bridge and found the officers on watch gathered around the ship’s radio, following the weather reports closely. A big cyclonic depression had developed 250 miles to the northwest, but it appeared to be moving away from us.

Small icebergs were scattered across the radar screen, and a sizable one loomed about six miles out at 2:00. At 12 knots and surging even faster in these following seas, even the Shuleykin with its hull strengthened for ice, could not risk a collision with something that size.

Back down in the lecture room, Russian-born naturalist Peter Ourusoff began briefing us about the wildlife we would encounter around South Georgia Island. “Leopard seals are widely regarded as the most dangerous killers of wildlife in Antarctica, yet it’s the big fur seal bulls in herds on the beaches that tend to be aggressive toward anything, including human beings, who wander into their territory.”

We would soon find out that he was not exaggerating.

By dawn the next morning, the Shuleykin was at anchor in Grytviken Bay at 54 17′ S, 36 30′ W, offshore from an historical Norwegian whaling station long since shut down.

Years of Antarctic storms had battered and crumbled the row of wooden structures ringing the little cove. Long before the seal hunters had come, the great British navigator Captain James Cook had anchored here when he discovered South Georgia Island in 1775.

The sky was overcast, but the wind was light and the weather seemed to be holding steady. At a signal from Olaf, we pulled on our dry suits and launched our kayaks from a landing platform that the crew had lowered down to the water.

We gathered into formation and began to paddle towards shore, where a jagged range of ice-clad mountains loomed above. A flock of swift macaroni penguins dove and leapt nearby, porpoising to get a better look at us.  My paddling partner, Lou Gibbs, and I landed our kayak on a narrow strip of sandy beach near the crumbling remains of the whaling station, while the other paddlers explored the waterfront by kayak.

My paddling partner, Lou Gibbs, and I landed our kayak on a narrow strip of sandy beach near the crumbling remains of the whaling station, while the other paddlers explored the waterfront by kayak.

We knew that the legendary Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton was buried here somewhere. In 1915, after his ship the Endurance became ice-bound in the Weddell Sea and was ground into splinters, he and his men subsisted for months on pack ice.

When the pack ice finally broke up, they sailed their two lifeboats to uninhabited Elephant Island, where they found scant shelter from the Antarctic weather in a rocky cave. Shackleton then took a few of his men and sailed 800 miles in the most seaworthy of the two boats, through the storm- and iceberg-filled Southern Ocean.

Their long sea journey climaxed in a surf landing on the blustery west coast of South Georgia Island. Even then, however, their trials were not over. Protected only by the tattered rags that remained of their clothing, they climbed across the glacier-covered mountains to reach the whaling station at Grytviken. Incredibly, not one of the Endurance crew perished during the eighteen months they were lost in Antarctica.

When a journalist back in England asked Shackleton if he considered his expedition to be a success or a failure, he replied, “A successful expedition, sir, is one from which all hands return alive.”

Story and Photos by Michael Powers