I enjoy kayaking in the rocks outside San Francisco’s Golden Gate, so I was happy to see a post from Bill Vonnegut about paddling north from Rodeo Beach. When hearing there might be a lot of paddlers from our club (Bay Area Sea Kayakers, BASK) for this outing, I was delighted at the chance to kayak with some folks I might not have seen in a while.

I even thought the large group might afford the opportunity for a little rescue practice. Ultimately there were about 22 people on this trip. Another smaller contingent with another four to six BASK kayakers started shortly after our group.

We paddled off the beach into 3- to 4-foot waves. Most of the waves we encountered after leaving the shore were much smaller. On this relatively benign day we headed north up the coast, much closer to the rocks than is typically possible for the area.

With this sort of club trip it is not likely, nor necessarily even desirable, for everyone to stay in one large pod, so it wasn’t long before we were in groups of about four to six people.

We stopped to play in the passages into caves and through arches and we rode waves through slots between rocks or over them. Groups split apart, swapped members and merged into new groups.

That there was not a single paddler that day who lacked the skills or experience to be out there made this an easy affair. There were capsizes with and without wet exits, as well as a few simple rescues throughout the day, but we were all having a great time.

Ciaran:

It was a nice day with very little wind and maybe-two foot swells. Usually they’re bigger than this. Shortly into the paddle, Tony Johnson and I negotiated a small pour-over at the same time. I tried to make a hard left turn to avoid Tony.

I went over and rolled back up again. No big deal. I hit the pour-over a few more times, and, I have to say, I was having fun. Then I got hung up on a rock and went over again. My bow got stuck on a rock and I blew my first two roll attempts. As I was setting up for a bomb-proof roll, I saw someone’s bow next to my boat so I did a bow rescue instead. Conditions seemed very calm and my guard was probably down a bit.

I paddled back outside and someone asked, “How many times have you been over already?” I said, “two,” and thought to myself, this is going to be a long day—possibly a 14 mile paddle—and I should probably dial it down a bit.

Gregg:

Because of my penchant for play and exploring, I tend to find myself taking up the rear in the group on any rock-garden trip. As I rounded one bend, a large arch came into view. There was a large group of people sitting a bit outside the arch. It seemed as if folks were just casually chatting, but then I heard someone say something about someone getting flushed from “there.”

I didn’t know where “there” was, but then I saw Ciaran abruptly appear, flushed from a cleft in the rock. He was out of his boat and hanging onto a toggle. Just as suddenly as he appeared, Ciaran and his boat were sucked back into the crevice. Several of us started shouting at Ciaran to let go of his boat and just swim out. I couldn’t tell whether he could hear anyone or not.

Ciaran:

There was a big arch that some kayakers were playing in and to its right there was a small slot. I was observing the slot for a short time when I saw someone do a little pour-over inside the slot and come out at the front of the arch. I observed a little longer and decided I was going to go for it. So much for my decision to dial it down.

I went into the slot on the next surge but wasn’t fast enough and landed on top of the pour-over. No big deal, I figured, I would just wait for the next wave to carry me through to the front of the arch. The next wave came in but, instead of washing me through to the front of the arch, it sucked me back into the back of the slot.

I completely failed to anticipate this. I went into combat mode. There was a lot of whitewater around me and I went over. I rolled back up, tried to paddle forward in the slot, but it was only three- to four-feet wide. The next surge came in and sent me back even farther and rolled me upside down again. I thought bailing out was not an option and would make things very difficult. It was too narrow to roll but I managed to push off the bottom to right myself. I headed for the exit only to be hit again by the incoming surge and sent back to the back of the slot.

I think I went over again and managed to right myself by climbing up the side wall. There was no room to roll. At that point I was feeling this was becoming a bad situation and attempted to rush for the exit again. The next surge sent me flying backward again. My boat got stuck sideways between the two walls and I was sucked out of the cockpit.

I hadn’t been unintentionally out of my boat in about three years and thought, “This isn’t going to be good.” The water pulled me down and under what seemed to be a ledge underwater. I was held there for what felt like a long time. When the surge subsided, I made for the exit again, grabbing my boat along the way and trying to swim with it and the paddle. I guess this was instinct—“never lose your boat or your paddle.”

After the surge came in and out a couple more times, I could no longer hold onto my boat so I let it go. The boat came back and forth, crashing into me a bunch of times so I held onto it again. I even thought, “If I hold onto the boat, I might get washed out to the exit with it.” At one point I tried to climb on top of the boat, but that didn’t help any. I was held under the ledge for about twenty seconds at a time, and drank a lot of water.

Gregg:

Though the outside swell didn’t rise above 3–4 feet, the effect was amplified in the tight confines of the slot, causing the water to slosh in all directions at once, creating standing waves in a clapotis effect.

Given the way the water was sucking in and out of there, creating lots of strong currents and whirls and alternately exposing the mussel-encrusted rock or pounding it with whitewater, it seemed debatable as to whether another boat in there would make the situation better or worse.

Jeff, a Class-V whitewater boater, paddled his whitewater boat into the melee and attempted to rescue Ciaran. He left me with the bag end of his tow rope but I very quickly had to let go as it was not long enough, and my holding onto it was preventing Jeff from paddling in.

Even with a slack rescue line Jeff still went in. By this time Ciaran, despite having on his PFD, was repeatedly disappearing beneath the waves. He would only be gone for a few seconds, but those seconds seemed to stretch out when he would not immediately pop to the surface.

Ciaran:

After about ten minutes in the slot I was feeling fatigued. Jeff Hastings came in with his small blue riverboat and tried to extract me. We both got bashed around back and forth in the surge. Jeff rolled at least once but, no matter what, I couldn’t seem to hold onto his boat.

Jeff is a very strong kayaker and, at first, I really thought he was going to drag me out of there. He also inspired me to keeping fighting. He told me to let my boat go which I think I did but was concerned about it hitting me again. I felt like a pin in a bowling alley.

Someone threw in a throw rope which I grabbed and started to reel in. After I reeled in about 50 feet, I realized there was no tension on the other end. So I let it go. The next surge wrapped the rope around my body and legs, which I managed to brush off. I ended up in the back of the slot again, under the ledge.

Gregg:

Jeff reached underwater a few times to pull Ciaran to the surface. Unfortunately Jeff was getting banged around pretty hard as well and was over a few times, but he always managed to roll up. Once when the area was sucked partially dry by the incoming swelI, I saw Jeff’s boat wedged upside down between two rocks inside the crevice. It’s a testament to his skill that he didn’t end up out of his boat himself.

Still, despite all Jeff’s efforts, Ciaran never had the strength to hold on when Jeff would attempt to extricate him. And the longer Jeff’s boat was being tossed around in there, the greater the chances of injury to Ciaran and the chances of him becoming a victim himself. Ultimately, Jeff was forced to abandon his efforts in the slot.

At some point during all of this, Ciaran’s boat finally got washed out and Bill and others grabbed it and took it out of the way. I could see Ciaran’s expression clearly during one of the times he came to the surface. The look on his face was grim at best.

Ciaran:

Jeff, my boat and the rope were gone. I felt myself being sucked under the rock and let go a bunch of times. I certainly got my money’s worth out of my helmet. It was a pity it did not cover all of me. I felt like I was in a giant toilet lined with rocks and being flushed every ten or fifteen seconds. I had no energy left and could not fight anymore.

I felt I had done 15 rounds with Mike Tyson and was setting up for another 15. I realize now that after all that struggling I was not getting close to the exit at all. First I was angry and then I was accepting of my fate. I was quite sure I would die. I told myself that my wife and kids would be okay and tried to picture them.

It came to a point that I thought I would go under the rock only one — maybe two — more times. And that would be it. I had swallowed a lot of water but still had not inhaled any. For a fleeting moment, I considered inhaling water to bring the inevitable end on quicker. Then I pushed this idea out of my mind. I only hoped it wouldn’t take too long and not hurt too much.

Gregg:

I was desperate to try another tactic and thought about climbing onto the rock outcropping close to the arch. I paddled to the arch side figuring the currents would be easier to deal with there and scouted the options. I hadn’t yet committed to that decision though and went back to check on the progress.

Tony, a very experienced sea kayaker, had been having the same idea but he had committed to his course of action. He told me he was going to jump out of his boat and clamber onto the rock and asked if I would take care of his kayak. I agreed and suggested we do it on the arch side of the rock where I had just been scouting.

Tony, full of adrenaline, was already heading in that direction. He and I paddled to the north side of the rock outcropping. Once there, Tony quickly exited his boat and swam to the rock. I held his boat and tossed him my rescue belt. By this time Jeff had arrived near us.

I think he was also thinking of jumping on the rock. As I was already exiting my boat, Jeff instead helped organize folks to take care of the kayaks after I’d released them to swim to the rock.

When I arrived at the rock, I set my paddle as high up on the rock as I could without it being in the way of the precarious footing available to Tony and me. At some point, I have no clue when, my paddle was washed away by the waves repeatedly washing over the rock.

By this point, Tony had thrown a line into the slot. Fortunately it landed right over Ciaran’s shoulder. He was now wedged toward the back of the crevice and while still splashed by the waves, he was no longer in the water and being battered about.

Ciaran:

After about twenty minutes, I started to hear Tony’s voice and then saw him standing on a rock above and to the left of me — about 20 feet away. I was in a daze at this point. My arms and legs no longer worked. To be honest, I found him a little annoying. I figured these were my last moments and I wanted to be in peace. He was disrupting this.

Tony is a great friend and kayaker and consistently manages to inspire me; he seems to always say the right thing at the right time. I remember him saying, “Be strong, Ciaran.” It is something he says a lot. He kept saying, “Grab the rope, grab the rope.” I made one last attempt, figuring he was not going to go away, so I may as well make an effort.

Gregg:

At this point Ciaran had probably been in the water about 15 minutes. He was hypothermic and physically exhausted from his struggles, had swallowed lots of water, been beaten by the rocks and his own boat, and was now suffering a post-adrenaline-rush crash.

There was no way for him to climb out from his perch, and jumping back into the water was not an option either.

Tony had to very forcefully yell at him to “Stay strong!” while giving him directions about what to do with the rope. Despite the wave noise, Tony heard the click of the carabiner around the rope; he gave the word and Ciaran jumped back into the water.

There were brief moments when the surge pulled him toward us, allowing us to reel in the rope. But it seemed most of the time we were tugging for all we were worth to keep him from being pulled back into the crevice. The opposing forces of the fast moving water rushing like a river in the crevice, and Tony and I struggling against it, caused Ciaran to slide just beneath the surface as the water rushed over him. Seeing that made us more determined to hold on, and we eventually worked him alongside the rock we were standing on.

Ciaran:

It took everything I had to wrap the rope around myself and click the carabiner onto it. The rope tightened around me as Tony pulled me out toward the exit. He tried to pull me up. Then I noticed Gregg Berman standing behind him, also holding the rope.

I saw the next surge coming down and I tried to hold onto the rocks. I don’t know if I was any help. We all nearly ended up in the slot. They pulled me farther and farther toward the exit and then up onto the rocks. Gregg reached out and said, “Take my hand,” which I did. At this point I actually thought for the first time that I might make it. I was completely exhausted.

Gregg:

We were at least ten feet above Ciaran and the rock was too steep to even consider attempting to haul him up the face. From my position, I was able to back up to a lower, though more wave-washed portion of the rock while maintaining my hold on the rope.

Once I was set, we timed it and Tony let go of the rope and I pulled Ciaran, now in a much weaker part of the current, the last few feet to the rock. As he got there, I yelled for him to take my hand and initially got no response despite the fact he was looking right at me. I yelled again and he slowly reached out his hand. It was a struggle for Tony and me to haul him onto the rock and initially he just lay there face down trying to recover.

I was now more afraid that he was going to be washed off the rock, and no matter which direction he was taken, it would not have been good. My language became quite dictatorial as I barked like a drill sergeant that no matter how tired he was, he had to move his butt higher up the rock. While Ciaran attempted to crawl, we hauled him higher onto the rock just before the surge washed over the spot where he had just been lying.

Ciaran:

Tony and Gregg held on to me, asked me questions and tried to get some life back into me. I told Tony, “I have to rest. I can’t move anything.” I had never felt so helpless. I guessed this was what being paralyzed feels like. At least once a wave almost washed us off the rock, so we moved up higher.

Gregg:

As we turned Ciaran over, I noticed how dark purple his face had become. He was conscious and talking, even if totally spent. I quickly checked him over and he eventually was able to sit up.

Ciaran had fought beyond what we might typically be capable of and was completely exhausted. I wanted to get some calories in him before he crashed further. I always keep a few strips of fruit leather or energy bars in my PFD. Initially Ciaran could not eat, though he ultimately managed to slowly get some of the food down his gullet.

Other members of our group were rafting kayaks so Ciaran could be hauled away from the rocks to a landing site. Ciaran was lucid and had some energy coming back and he, Tony, and I decided if we could get his boat on the rocks and get him in it, that would be the best solution. His boat was brought to us and Tony and I held it in place while Ciaran climbed in and took up his spare paddle.

When the swell rose again and the group in the water was ready, we pushed and Ciaran easily slid down the steep rock to the kayakers waiting below to catch him.

Ciaran:

Tony and Gregg pulled the boat up onto the rocks and I managed to climb back in. They snapped on my spray skirt, assembled my spare paddle, and launched me down the rocks into the water. I managed a little brace and stayed upright. It took all I had to stay upright.

Gregg:

Tony and I then moved to the farthest seaward portion of the rock to prepare to reenter our boats. It wasn’t until someone offered me my paddle that I even realized it had been gone. I jumped in the water and paddle-swam to my boat and Tony swam to his.

At this point Elizabeth and a few others were rafted up with Ciaran and supporting him. It was agreed that we would do a rafted tow with another paddler holding on to Ciaran to support him while we headed back to Rodeo Beach. I clipped on and started a tow.

Anders quickly offered to help with an in-line tow and attached to my bow. Tony clipped to Ciaran’s boat as well, so now we had both an in-line and a husky tow on the same boat.

After we’d covered about half the distance back to Rodeo Beach, Ciaran regained enough strength to balance himself without being rafted up with a supporting paddler. With just a single boat in tow, the work was much easier. He still had a kayaker paddling on either side of him though, just in case. By this point he was much more communicative and doing much better. We all even joked about the new feature we would name in his honor, “Ciaran’s Crack.”

We decided to paddle to the southern part of the beach. It was farther from our cars but it had much smaller surf. As we neared the beach, Bill paddled in first to assist with the landing. Before crossing the surf zone we disengaged our tows for the paddle in. Ciaran said that he had lost his contact lenses and could barely see. I jokingly promised him I’d go back and look for them. We didn’t want to risk any more calamity with a collision in the surf so with Bill on the beach to catch Ciaran, I escorted him the last couple hundred feet through the surf zone. We timed it well and had an uneventful landing.

We all headed up to the cars, and as we were getting Ciaran changed into dry clothes, Lynnette, Tony’s wife, appeared. She had been hiking on the bluffs overlooking the coast. When she saw a contingent with Tony’s boat moving “too slowly” back to the beach only a short while after launching, she knew something was amiss and came to meet us.

There had been talk of getting Ciaran to a hospital. Jeff had been worried about the risk of secondary drowning, where your lungs fill with your own body fluids up to 72 hours after a near drowning as they try to clear themselves of any contaminants. There had also been talk of someone driving him home. At this point, however, his breathing was doing great. Despite the large amounts of water he surely swallowed, it seems little entered his lungs, as not once did I notice him cough from the time we pulled him onto the rocks till we got him safely back to the put-in.

With his strength returning, warm clothes, plenty of food, a public place with lots of resources and Lyn and Anders to stay with him, we decided to just let him rest and recover before determining whether he was safe to return home on his own.

The rest of us headed back to the water to reconvene with the rest of the group. Anders stayed there quite a while and Lynnette talked with Ciaran for at least three hours there in the parking lot to help him sort his experience.

Lessons Learned

Gregg:

I had heard of BASK long before moving to California and joined shortly before I moved out here.

BASK provides ample opportunity for a whole host of training sessions, most of which are free or only of minimal cost to members and are run by other members. The club also promotes classes conducted by professional instructors. Each summer we select about a dozen lucky participants to take part in our annual monthlong skills clinic.

You would be hard-pressed to find a more thorough mental and physical course on paddling. On this particular outing, being in a club like BASK gave the group an advantage. Most of the participants were either graduates of, or instructors for the BASK skills clinic. Most had organized or participated in club skills and rescue practice sessions. And of course we all have the benefit of the online forum on a wide range of topics with lots of lively discussion on all aspects of paddling.

Ciaran himself commented that he had already had a few problems that day and should have dialed things down a bit. That’s a judgment call only he could have made.

The people on the water I respect the most regardless of skill level are not the ones who blindly rush into everything they see or try to impress or keep up with or be cajoled by their friends.

The people I am most impressed by are the ones who have the personal strength to say, “You know, I think I’m going to pass on that,” or “I’m just not feeling it today.” That is not to say you shouldn’t push yourself or be complacent, but rather you should push yourself only when you feel it appropriate. On some days it may be appropriate and on others not. I look for that kind of attitude in those that I paddle with and try to cultivate that sensitivity in myself.

Tony, Bill and I had no indication that something was amiss when we approached the scene where Ciaran was in trouble. Perhaps everyone was just too involved in what was going on and didn’t expect the situation to continue for the length of time that it did.

It should be common practice to blow some whistles, raise some paddles or in some way alert others to an emergency situation. If things resolve themselves for the best, then great, no harm done, but if they don’t, then more resources become available when more folks are aware of something going on.

After we delivered Ciaran to the beach, most of us resumed paddling. Later in the day I helped rescue someone else I saw come out of their boat. Calling it a rescue seems ridiculous compared to earlier events, but I did not blow a whistle before going in. I should have in case it had turned out to be more involved.

At another time near the end of the day, I also capsized in the rocks and while I rolled up and got out fairly quickly, would it have been prudent for those who witnessed it to alert others until I was not only upright but back out of the rocks? A simple whistle blow to alert others just to be on the lookout likely would never hurt. And for an incident that continues, being a bit more vehement in your signaling to actually draw others near then becomes imperative.

Some of the group members later asked me about the decision to call or not call the coast guard. Anders wondered whether he should push the alert on his satellite messenger. Deciding when to use distress signals is a worthwhile debate. As previously mentioned, this situation just continued to drag on in a manner that nobody expected, but then the worst is never expected. When should a call have been made and how do you decide? Should it have been done in this case?

Well, when I spoke with the coast guard following the rescue of Ciaran, they said to call any time you suspect trouble. They recommended calling early. They further stated that calling on VHF radio channel 16 (as opposed to by cell phone) had the advantage of reaching the coast guard but also other boat traffic in the area.

A commercial or recreational vessel nearby could potentially respond even before the coast guard got on scene. In our situation there was a fishing boat sitting within close sight of us. They might have been able to get Ciaran to safety without our having to put him back in a kayak to leave the area. Instead, they remained unaware of our plight.

I always have food in my PFD as a safeguard against hypothermia, fatigue or even just getting cranky from lack of food. For Ciaran I wished I’d had something other than a very chewy fruit leather. In a truly weakened state such as Ciaran’s or a diabetic reaction, it simply takes too much energy to chew and swallow.

In the future I will carry a tube of glucose paste or cake frosting in a PFD pocket. The tubes are small, the paste need not be swallowed (though it can be), as it will absorb through the oral membranes. Thus it is less likely to induce vomiting, is more quickly absorbed into the bloodstream, and is a readily available source of energy.

Warm fluids are great and can be helpful as much psychologically as physically. Be careful though; if they are too hot, consider diluting them with some cooler liquid to avoid the risk of burning the recipient.

I was happy to have my paddle for the swim to and from the rock. Swimming with a paddle is something I often practice just for fun. It comes in handy when wearing full kayak gear, and over the short haul it dramatic improves your swimming speed and power when done right.

Though the rescue knife I carry on my PFD gets used most for spreading peanut butter or cutting foam for outfitting, it’s great to have when it’s really needed. In this case it was only used to regain as much of the anchored towline as we could.

But if something had gone wrong while pulling Ciaran in, it would have been invaluable. I keep it on my left shoulder for easy grabbing with my right hand. I have used it many times to cut sea birds free from fishing line. A knife that won’t be corroded by salt water is best for use in the marine environment.

It is important to be aware of the possibility of secondary drowning. If someone gets too much water in their lungs, the subsequent filling of the lungs with fluid from within the body requires medical treatment even if that person seems to be fine.

This holds true whether you are in salt water or fresh water. Of course the importance of keeping your certification current in first aid, wilderness first aid and/or CPR can’t be overstated. While Ciaran managed to keep from inhaling any water, at least two of us in the group knew to look for signs of secondary drowning before we determined he was safe to go home.

It doesn’t matter how long you’ve been paddling or what your skill level is, taking advantage of additional training is always worthwhile. After more than 17 years of paddling and teaching, I know that the more experience I get, the more I realize I have to learn.

Every change in your gear or routine merits more practice. Something as simple as a new whistle on your PFD can throw a whole new wrinkle in your T-rescue if it gets caught on your deck lines as you try to climb out of the water.

You never know what an emergency will require of you. Anything you can add to your bag of tricks to help you assess situations and solutions may just make a very big difference. Practice everything and practice often. Tony and I have both paddled extensively and participated in numerous training sessions, including time spent practicing self-rescues and swimming to and from rocks with a boat in tow.

The attempts to perform a rescue by kayak, while valiant, were not working. Had we remained in our boats there would have been little else we could have done for Ciaran. I believe it is this training that prompted both of us to come to the conclusions we did independently, and made it possible for us to swim to the rocks where we were in a position to help each other with Ciaran’s rescue. Tony’s decision to dump his boat and climb on the rock may have saved Ciaran’s life.

Ciaran:

Three weeks after the accident I went paddling again for the first time. We did the same trip and made it all the way to Stinson this time. The waves were much bigger than the last time. We all stayed outside for the most part. The slot beside the arch looked a lot different.

I have been paddling for about five years now and consider myself a reasonably good kayaker. It still bothers me that I did not see the danger in that slot. It did not look like a big deal at the time, nothing I hadn’t done before. I hope I recognize this situation in the future.

I can’t say for sure that I will and this does bother me. I hope I don’t start second-guessing everything I do. Hopefully I will get my “mojo” back soon. I love kayaking and I want to keep going out as long as I can get my dry top on by myself.

I truly believe that if Tony had not dumped his boat and climbed up on the rocks, I wouldn’t be here now. I don’t think I would have responded to anyone else’s voice when I believed I was in my last moments.

I can’t thank everyone enough who helped in my rescue. Because Tony, Gregg and Jeff took action, my 11-year-old daughter and my 8-year-old son won’t have to say, “Yeah, we miss our dad, he died in a kayak accident.”

Thanks to Tony Johnson, Jeff Hastings, Elizabeth Rowell, for helping piece together the events. After this incident Glenn Nunez set up a rescue practice and Q&A; session with the local Coast Guard Station. Finally thanks to all of the Bay Area Sea Kayakers for providing critical training, support and feedback when events like this happen.

Gregg Berman is an ER nurse living and playing near San Francisco. He spends time as a tide pool naturalist or teaching kayaking and has been an expedition leader around the country from the Florida Everglades to the Alaskan glaciers.

Ciaran, a native of Dublin, Ireland, moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1987 at the age of 22. He is a building contractor, married with two children, living in Sonoma County. He started kayaking six years ago, after his wife bought him lessons as a Christmas gift, a decision she has regretted only occasionally.

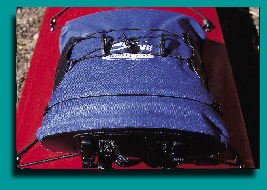

is made from PVC-coated polyester in a simple, tapered shape, with no external pockets, save a mesh one at the rear big enough for sunscreen or a small water bottle. The bungies running across the top will secure (not very well) a chart in a ziplock.

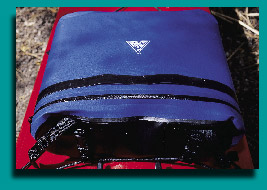

is made from PVC-coated polyester in a simple, tapered shape, with no external pockets, save a mesh one at the rear big enough for sunscreen or a small water bottle. The bungies running across the top will secure (not very well) a chart in a ziplock. The Aleutian is made from urethane-coated Cordura nylon, with welded seams. The bag is stiffened with a polyethylene sheet into a flattened ovoid shape that uses all of its modest 620 cubic inches efficiently. The zipper arcs over the top of the bag about three inches from the rear, so the back doesn’t fold down like a flap-you have to just push down on it to access the inside. Still, it works fine, and there’s a fabric flap that covers the zipper to help keep out grit. The bag is tall enough to hold my SLR camera (if I leave off the motor drive), and wide enough for a couple of extra lenses, plus a field guide and snacks-in other words, it has all the room you’re likely to need. Yet at only 12 1/2 inches wide (compared to 20 for the Watershed, including the clips), it’s compact enough to fit any deck.

The Aleutian is made from urethane-coated Cordura nylon, with welded seams. The bag is stiffened with a polyethylene sheet into a flattened ovoid shape that uses all of its modest 620 cubic inches efficiently. The zipper arcs over the top of the bag about three inches from the rear, so the back doesn’t fold down like a flap-you have to just push down on it to access the inside. Still, it works fine, and there’s a fabric flap that covers the zipper to help keep out grit. The bag is tall enough to hold my SLR camera (if I leave off the motor drive), and wide enough for a couple of extra lenses, plus a field guide and snacks-in other words, it has all the room you’re likely to need. Yet at only 12 1/2 inches wide (compared to 20 for the Watershed, including the clips), it’s compact enough to fit any deck. bottle, and still had room for my Gore-Tex shell when the morning turned warm. A stiffening sheet maintains the bag’s shape (and, as with most of these bags, is removable if you don’t want it).

bottle, and still had room for my Gore-Tex shell when the morning turned warm. A stiffening sheet maintains the bag’s shape (and, as with most of these bags, is removable if you don’t want it). Seattle Sports model, the inside of the Salamander bag stayed dry during what I’d call a fair-weather paddle-light breezes and small waves. I could have had a field guide inside with no worries. But when subjected to direct spraying or dunking the zipper leaked a small amount of water almost immediately, mostly through the small gap visible at the end of the zipper track.

Seattle Sports model, the inside of the Salamander bag stayed dry during what I’d call a fair-weather paddle-light breezes and small waves. I could have had a field guide inside with no worries. But when subjected to direct spraying or dunking the zipper leaked a small amount of water almost immediately, mostly through the small gap visible at the end of the zipper track. The paddle bridge requires the kayaks to be nearly parallel and just far enough apart to rotate the victim up between the kayaks.

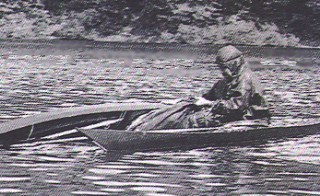

The paddle bridge requires the kayaks to be nearly parallel and just far enough apart to rotate the victim up between the kayaks. It’s also better for the rescuer’s kayak to be parallel to that of the victim to prevent a collision, and allow the rescuer to grasp the bow or stern of the victim’s kayak. By holding the bow and bridging his or her paddle across both kayaks, the rescuer’s bow is automatically at or near the victim’s hand. Another advantage is that the rescuer can keep the bow from swinging out of reach during the rescue by moving the lower body.

It’s also better for the rescuer’s kayak to be parallel to that of the victim to prevent a collision, and allow the rescuer to grasp the bow or stern of the victim’s kayak. By holding the bow and bridging his or her paddle across both kayaks, the rescuer’s bow is automatically at or near the victim’s hand. Another advantage is that the rescuer can keep the bow from swinging out of reach during the rescue by moving the lower body. There are also Eskimo rescues for extreme situations, where a kayaker might get out of the kayak and have to be carried piggyback on someone’s afterdeck. This is extremely dangerous in cold water. There was a poignant story told by Dr. Alfred Bertelsen, a medical researcher in Greenland around 1900. Three brothers were out hunting in kayaks when one of them capsized. He exited his kayak after failing to roll up. His brothers managed to get him up between them, but he froze to death in their arms.

There are also Eskimo rescues for extreme situations, where a kayaker might get out of the kayak and have to be carried piggyback on someone’s afterdeck. This is extremely dangerous in cold water. There was a poignant story told by Dr. Alfred Bertelsen, a medical researcher in Greenland around 1900. Three brothers were out hunting in kayaks when one of them capsized. He exited his kayak after failing to roll up. His brothers managed to get him up between them, but he froze to death in their arms.