Leaving my kayak in a scraggly stand of stunted spruce trees at the bottom of the 70-foot waterfall, I hiked up to the top of the falls to fix my lunch. I settled myself on a rocky granite ledge at the top of the waterfall and started cooking my lunch on the stove beside me, as my feet dangled in the cool mist. Suddenly, I noticed a stranger walking up the steep path toward me. He had long black hair and a beard, and was wearing mud-streaked pants and a baggy sweater that hung loosely around his thin frame. A mosquito head net flipped up over his head was held in place by a red bandanna. Approaching, he sat silently down beside me.

Leaving my kayak in a scraggly stand of stunted spruce trees at the bottom of the 70-foot waterfall, I hiked up to the top of the falls to fix my lunch. I settled myself on a rocky granite ledge at the top of the waterfall and started cooking my lunch on the stove beside me, as my feet dangled in the cool mist. Suddenly, I noticed a stranger walking up the steep path toward me. He had long black hair and a beard, and was wearing mud-streaked pants and a baggy sweater that hung loosely around his thin frame. A mosquito head net flipped up over his head was held in place by a red bandanna. Approaching, he sat silently down beside me.

I offered him some gorp, and he nodded and took a handful. After a few munches, he finally spoke: “Nice breeze, no bugs.” Feeling somewhat unnerved by the man’s demeanor, I asked him if he wanted some water. He shook his head and helped himself to some more gorp. As I stirred the boiling noodles, my curiosity rose.

We were deep in the woods on the Pigeon River, near the Canadian-Minnesota border-a long way from any road. I was traveling alone, and hadn’t seen a soul in more than three days. In the 12 days since I had climbed into my kayak, I had already paddled 250 miles down the fur trader’s historic border route over 32 lakes and down three rivers. I had carried my gear and kayak over 30 portages and, if my luck held, I would get to the infamous nine-mile Grand Portage that leads to Lake Superior in just a couple of hours.

Since the start of my trip, I had been charged by a mother moose, been harassed by bears, waded through thigh-deep mud on portages, and run numerous unmarked rapids in my 18-foot sea kayak. Through it all I had been tormented by hordes of bloodthirsty mosquitoes that would make a preacher swear. I had come to take all of this as part of a normal day, but this guy was definitely out of the ordinary.

He finished the gorp and, picking up my spoon, began eating my noodles. He paused for a second and said, in a heavy French accent, “I thought you were dead.” My eyes narrowed as I said, “Excuse me?” He spooned in another huge mouthful and said, “There were two otters playing in your kayak at the portage, so I just assumed you had drowned and it had washed up on shore-but by the delicious taste of these noodles, I see that I was wrong.”

Then his story began to emerge. He was Kim Haffez, a 27-year-old Frenchman on a solo, two-year canoe trip from Montreal to Tuktoyaktuk, on the Arctic Ocean. After he finished my entire lunch, we hiked down to the bottom of the falls. A mountain of gear was heaped next to a red, 16-foot fiberglass canoe.

A shotgun, three spare paddles and snowshoes jutted out of the jumble, as well as a saw and an ax – so that he could build a cabin when the rivers froze. He told me that he didn’t wear a life jacket or a wetsuit; since he already had to make five trips over every portage, he refused to carry another thing. He had been wind bound seven of the last nine days on Superior, and had run out of food. He had lost 15 pounds before he re-supplied in Thunder Bay. He had then headed up the Grand Portage, where our paths now crossed.

I tried to get him to take my detailed maps of the border area to replace his one large topo map that didn’t have any portages marked, but he refused. He said he wasn’t in a hurry, and he would eventually find them. He wished me well and, as we shook hands, I slid my last candy bar into his palm. We departed in opposite directions.

It was time to go – we each had dreams to chase.

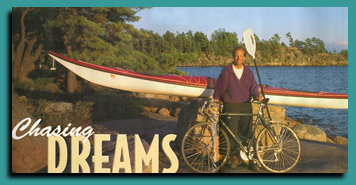

I had begun my biking/kayaking journey on May 20, in Vancouver, British Columbia. From there, I biked to the small Minnesota outpost town of Crane Lake. From there, I planned to paddle down the border route through the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and Superior National Forest. After I carried my kayak and gear down the Grand Portage, I would paddle another 700 miles along the north shores of Lake Superior and Lake Huron to Parry Sound, Ontario, where I would switch back to my bike and pedal the rest of the way to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia.

I had begun my biking/kayaking journey on May 20, in Vancouver, British Columbia. From there, I biked to the small Minnesota outpost town of Crane Lake. From there, I planned to paddle down the border route through the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and Superior National Forest. After I carried my kayak and gear down the Grand Portage, I would paddle another 700 miles along the north shores of Lake Superior and Lake Huron to Parry Sound, Ontario, where I would switch back to my bike and pedal the rest of the way to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia.

My wife, Molly, met me at Crane Lake to exchange my bike for the kayak. I would meet her in seven weeks in Parry Sound to switch back to my bike. She gave me a long hug good-bye, then I slid my kayak into the brown, tannin-stained water. During the first three days, I paddled from Crane Lake down the sluggish Loon River, then across the 20,000-acre wind-buffeted Lac La Croix. In the process, I strained a set of muscles I hadn’t used in a while, and developed blisters on my hands.

Late in the afternoon, at the end of Lac La Croix, I rested the paddle across my spray skirt, stretched my back, and scanned the steeply rising shoreline of birch and pine trees for the faint trail that would lead out of Lac La Croix into Bottle Lake. I thought out loud, “If I were an Ojibway or French fur trader and didn’t want to carry my load one step farther than I had to, where would I cross overland?” Then I spotted a small depression in the green canopy at the far end of the bay, and I thought I could make out a trail leading up from the shoreline.

As I began to paddle, out of the corner of my eye, I could see a small black object in the water near the shore, moving toward me. I gritted my teeth and muttered, “Not another one!” I sped up my pace. About 50 feet away, an explosion of water mixed with a blur of black and white. A large loon flapped its wings furiously on the water and let out an ear-splitting yodel. I tried to disregard him, and kept paddling. Yelling, he continued after me in angry pursuit. What was with these loons? I was prepared for bears in camp, angry moose on the portages, deadly afternoon thunderstorms and swarms of biting insects, but I had never anticipated that I would be the victim of a loon attack. I paddled faster, and the loon dropped back, but continued his aggressive displays and calling.

While kayakers are rare in the Boundary Waters, this is a popular canoeing destination for thousands of people every year, and I had never heard any source mention loon attacks. Kayakers aren’t that much different from canoeists. If it wasn’t the kayak that was setting the loons off, maybe it was my paddle. I looked down at the white plastic blades with the black letters of the manufacturer sprawled across them, and laughed. Of course! The flashing black-and-white paddle probably looked like a male loon defending its territory. It was their mating season. No wonder why every male loon I came across tried to drive me off.

Reaching the far shore, I lifted my boat up over the sharp rocks and found a flat place to set it down. I then took the pieces of my homemade portage yoke from behind the seat. After I placed the yoke across the kayak, I opened the front hatch and pulled out my bulky canvas Duluth pack. I crammed all of my stuff sacks into it and hoisted it onto my back, leaving my kayak for a second trip.

I had gone about a third of the way down the muddy, boulder strewn, half-mile-long portage when I ran into a balding, barefooted man with a big belly and tight T-shirt, loaded down and staggering under the weight of a bulky pack and an old aluminum canoe. An assortment of dented pans, dirty cotton socks and fishing equipment spilled from his bulging pack onto the trail. He was drenched in sweat and swearing profusely as a cloud of mosquitoes hovered around his head and arms. He couldn’t swat at them, or he would drop his heavy load. I stepped to the side and said, “hi,” as he passed. He grunted in acknowledgment and staggered on.

When I reached the far end of the portage, a smiling middle-aged man held a small black-and-white fox terrier that was encased in a bright orange life preserver. I said “Good morning,” and set my pack off to the side. He smiled and offered me some water. I asked him if the barefooted man was with him, and he shook his head. “He was heading off down the portage when I pulled up.” I nodded and went back down the trail to get my kayak.

On my way back to my kayak, I collected odds and ends that the sweating man had dropped. When I got back to the beginning of the portage, the barefooted man was sitting on the front of my kayak, rubbing his foot. I set down the pile of cookware and dirty clothing that I had picked up, and said, “I think that’s everything.” He grunted a thank you. I stood silently watching him for a minute, then asked, “Have you ever tried to do it in two trips instead of one?” He shook his head in disgust and said, “I just want to get these d– portages over as quick as possible.” I nodded, then asked, “I never thought about doing them barefoot-what’s the advantage?” He looked at me as if I had just asked him the dumbest question in the world, and replied, “You don’t get your boots all wet and muddy.” “Hmmm-I guess you’re right,” I said. “Well, if you don’t mind, I think I’ll keep going,” and I nodded toward my kayak. He sighed as he got up off my kayak, then hobbled over and plopped down over his pile of gear.

When I got back to the other side, the man and the little dog were sitting on the ground eating peanut-butter crackers. I reloaded my kayak, and as I shoved off into the gin-clear water, I asked him, “Have you ever thought about doing a portage barefoot?” He gave me a strange look, and I shook my head and said, “I didn’t think so.”

Four days later, I was paddling through the murky backwaters of the Granite River. As I rounded a bend in the river, the dark brown form of a partially submerged animal appeared a hundred yards ahead of me, near the left bank. I quit paddling and watched as the horse-shaped head and floppy ears of an adult moose slowly emerged from the silty water. A clump of stringy, grass-like water plants hung from her mouth as she chewed. She was thin and scruffy: Large clumps of winter hair were still falling out. Feeding ten yards from the near shore, she hadn’t noticed me yet. I glanced across the 200-foot-wide channel to the right-hand shore. I had already waded through three sets of rapids and made four portages today, and I was frustrated by my slow progress. I really didn’t want to wait until she was finished grazing, nor did I want to try to portage around her.

I angled my kayak toward the far shore and silently began paddling.

She lowered her head again, grazing. Just as I drew even with her, she suddenly lifted her head out of the water and looked right at me. The hair on the top of her back stood up and her ears lay down flat against her skull, and she let out a low, rumbling call. Just then I saw some movement behind her in the tall reeds. My heart leapt into my throat as I saw that it was a wobbly-legged baby moose. I immediately recognized the universal body language that said she was getting ready to destroy the threat to her baby. I began paddling frantically, but on my fourth stroke she charged. She bellowed like the bull on my grandfather’s farm as she plowed through the shallow water toward me. In an instant, I realized that I could never paddle fast enough to escape her. I dropped my paddle into the river and began waving my arms. When she was about 40 feet away, I began talking in a loud, but soothing, voice: “Easy girl, now…easy, EASY, I’m not going to hurt you!” She stopped abruptly in a shower of spray and stared at me. The hair on her back went down. Then she turned and charged back across the river to her baby, which she herded to shore. I sat for a few minutes until my heart stopped racing, then I retrieved my paddle from the water next to the kayak, and continued on.

Five days later, I sat on the shore of Lake Superior, soaking my blistered feet in the lake’s icy waters. I had just finished carrying my kayak and equipment over the grueling nine-mile Grand Portage. At three trips, it was a total of 27 miles in one day.

Just thinking of what I had been through gave me newfound respect for the Voyageur fur traders who made the same trip with 180-pound loads. No wonder most of them retired by age 35.

During my second night on Lake Superior, the wind began to blow steadily out of the southwest. In the morning, the wind was still howling. I crouched on the granite ledge that held my tent, and surveyed the dark sky and the whitecaps that rolled down the lake. The weather radio that I now held closely to my ear said that the wind was going to increase throughout the day. I thought about staying put, but there was a long string of islands running parallel to shore about a mile-and-a-half away. If I paddled out to those islands, I could get some shelter, regardless of the wind direction or intensity. With everything lashed down on deck, I paddled out toward the islands, into the whitecaps. While I was crossing a channel an hour later, the wind picked up considerably. Larger, eight-foot swells were moving up the main part of the lake and coming through the openings between the islands, where they were colliding with the waves from the channel. My kayak was tossed around wildly in the resulting five-foot standing waves. The farther I got from the protection of the shore, the higher the waves rose.

After struggling on for another hour, I was paddling between two tiny islands when a sudden, violent upswell tossed the bow of my kayak into the air and spun the stern quickly around, nearly capsizing me into the 40-degree water. I quickly paddled to the nearest island and pulled my kayak up the steep rocky shore as far as I could. The island was a barren rock about the size of a tennis court. At its highest point, it stood about 20 feet above the churning lake. Except for a solitary cedar tree that stood no taller than I, but was almost a foot thick at its base, the island had been scoured free of all vegetation. I struggled against the wind, making my way to the tree, and sat down at its base. The wind continued to rise and, by nightfall, it howled as it sent waves crashing into the island. On the lake side, the waves had risen to over 12 feet in height. I struggled to put my tent up and anchor it to the old cedar as the wind blew the froth off the tops of the breaking waves, splattering the rocks around me. I carried basketball-sized rocks up from the shore to hold the other corners. The wind rose to a shriek during the night as it picked up in intensity. A violent thunderstorm seemed to stall out over my barren rock, flashing and booming throughout the night as I lay sprawled in my flattened tent, praying that I wouldn’t be blown into the storm-tossed lake.

When I awoke the next morning, the storm was still raging. I began to realize that I couldn’t have picked a worse spot to be stormbound. I should never have left the mainland. Regardless of the wind direction, the shoreline would have offered better protection than these islands in a storm. Throughout the long day, I leaned against the cedar that pressed into the fabric of my tent, and tried to read a paperback novel, but I found myself continually watching and counting the waves as they crashed against the shoreline.

By evening, my appetite was gone and my stomach was tied up in knots. I didn’t even bother to fix dinner as I struggled to fight off the idea that the storm waves on this lake could perhaps grow large enough to sweep over this little island. By nighttime, my thoughts turned to quitting. Lake Superior might be too much for me. If I could ever get off this God-forsaken rock, I would turn around and paddle back down the shore to the Native American village of Grand Portage, and go home.

Sometime during the sleepless night, the storm broke. Exhausted after two nights with little sleep, I slept fitfully through the morning. By noon, I awakened to a lake that was as quiet as a farm pond.

With the change in conditions, my despondency of the previous night evaporated, and I pushed off into the lake to give it another try.

Five days later, I stared down into the transparent water as I paddled along. Today the hue of the water was light pink. Yesterday it was green, and the day before it had been brown. As the granite bedrock changed in color, so did the color of the water. I marveled at the perfectly formed bowling-ball-sized rocks that lay loosely in their three-foot-round, bowl-shaped depressions below me. The storm waves that have pounded this shoreline for thousands of years have pushed these rocks around and around, wearing down the bedrock and creating ball-in-a-bowl formations. I lifted my head for a minute and admired the massive granite headlands that rose hundreds of feet out of the lake. A young cormorant bobbed in the water a hundred feet ahead of me, next to a flotilla of gulls. The water was cold, the bottom sterile and lifeless. On shore, the first 20 to 30 feet was bare and rocky. Beyond this lifeless zone, knee-high willow and alder bushes sprouted, backed by ten-foot-high cedar and spruce trees. Unlike earlier in my trip, when I would see loons, ducks, eagles and osprey and the occasional bear, moose or deer, here I saw only cormorants and gulls. With no roads near this part of the lake, it had been days since I had seen another person, or even a boat.

A week later, I was paddling through heavy mist along the southern end of Pukaskwa Provincial Park, one of the most remote parts of the Lake Superior shoreline. I was 300 miles and 14 days from my put-in at Grand Portage. The heavy gray skies melted into the cold, gray water, making it difficult to separate the water from the sky. The moisture-laden air had worked its way under my paddling jacket. Peering through the thick morning fog, I thought that I could make out the dark form of an island in the distance. I strained my ears and thought I could hear the gentle hiss of waves breaking on a shoreline. I paddled toward the sound.

When I reached the island, I climbed out and pulled my kayak up on wave-polished, fist-sized stones. I walked up the beach a short ways and squatted to look at two four-foot-diameter round depressions in the beach. They were about three feet deep, and were made in a perfect circle. I had found similar pits scattered along the shoreline for the last couple of days. Scientists call these unexplained phenomena “Pukaskwa Pits.” Made by some of the earliest inhabitants of the region, they are estimated to be between eight and ten thousand years old. No one knows what their function was. Were they remnants of shelters, hunting blinds or storage pits-or did they have spiritual significance?

An old book I had read about the history of Lake Superior talked about an unusually large Pukaskwa Pit located in the center of this remote island. I pushed my way through the dense, wet tangle of alder bushes toward the center of the island. After an hour of scrambling through the dense underbrush, I was soaked, and decided to turn back. Suddenly, I caught a glimpse of a three-foot high, lichen and moss-covered rock wall through a tangle of willows. As I strode around the outside of the wall, I gauged that it formed a circle a hundred feet in diameter.

Inside the outer circle were five smaller symmetrically placed circles with slightly lower walls set at equal distances from each other. Towering cedar trees that were too big to wrap my arms around grew up out of the circles. The air was heavy and still as I stood in the center of the inner circle; the only sound was of water dripping off the leaves of nearby trees. I was filled with an overwhelming sense that I was in a very spiritual place. I picked up a small stone from the outer ring and slipped it into my pocket to remember this place.

Walking back to my kayak, I began to feel guilty about the stone in my pocket. I argued with myself that one small rock wouldn’t be missed, but after climbing back into my kayak and paddling for just a few minutes, I turned around and paddled quickly back. I returned the stone to the place I’d found it, mumbled an apology, and slowly walked back to my kayak.

The words of Gordon Lightfoot’s famous song, The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, ran like an endless tape in my mind to the rhythm of my paddle stroke. I was about 15 miles from Whitefish Bay, at the eastern end of Lake Superior. The song tells the story of the 750-foot ship that went down in a freak November storm. I was close to the spot where all 29 crew members had lost their lives. Paddling in warm, calm air beneath a sky that was bluer than the water, I was about as far from the terror of that storm as I could get.

I spotted a small object floating in the water a few yards ahead, and pulled alongside it. I reached down and scooped a small, bloated toad out of the frigid water. He had puffed himself up to keep from sinking, and was so cold that he couldn’t even move his legs. I looked at the shoreline a quarter of a mile in the distance, and wondered how long he had been floating out here. I set him on my neoprene spray skirt and paddled in toward a narrow opening between a line of rocks along the shoreline. When I passed through the opening, a shallow bay with a half mile of white sand shoreline spread out before me. By the time I pulled my kayak up onto the beach, the toad was starting to regain the use of its limbs, and began to move around. I set the toad in the sun in the shelter of a bleached and battered driftwood log. I sat on the warm sand and absorbed the silence and wildness of the area. It was hard to believe that I was only a two-day paddle from Sault St. Marie, and less than a long day’s drive from several large metropolitan areas. After about a half hour, the toad hopped up the beach and I went back to my kayak.

When I paddled into the mile-long channel leading into Sault St. Marie at the end of Lake Superior, the clamor of the modern world quickly overloaded my senses. Thousand-foot cargo ships lined up to enter the locks leading to Lake Huron, dwarfing my kayak. The acrid black smoke that poured from the smokestacks on shore burned my eyes and nose. Acre-sized piles of coal and iron-ore spilled over their retaining walls and into the water. The hum of hundreds of cars on the interstate bridge overhead blended with the roar of float-plane engines. As I sat, trying to absorb it all, a triple-decker tour boat cruised in a tight circle around me while tourists clicked away with their cameras. The four-foot wake of the vessel careened toward me, and I fought to stay upright in the confused chop.

Looking for a way around the St. Mary’s Rapids that separate Lake Superior and Lake Huron, I paddled down a narrow channel where most of the water was flowing. After a few hundred feet, a three-foot-high yellow sign said: WARNING: HYDROELECTRIC TURBINES AHEAD. I frantically paddled backward against the current for a hundred feet, and landed on a small gravel area. It appeared that I had no choice but to portage the half mile through town.

As I began unloading my gear, a stoop-shouldered elderly man who looked like he was on his way to church, in neatly pressed slacks and dress shoes, approached and struck up a conversation. Horace told me that he came down every morning to watch the boats pass through the channel. When I told him about my dilemma, he said, “Wait right here!” He hurried off, and a minute later backed his dilapidated, green ’67 Chevy truck up to my kayak. We slid my boat into the rusty truck bed, and a few minutes later I was launching on Lake Huron.

In the first two days on Lake Huron, I had already seen more boats, houses and people than I had seen in 23 days on Lake Superior-but I wasn’t complaining. I had traded my wetsuit for a T-shirt, and there were still hundreds of miles of undisturbed shoreline to enjoy-not to mention the opportunity to finally go for a swim. I stood on the smooth boulder ten feet above the warm waters of the North Channel. I could see the bright flash of sailboats dancing on the water in the distance. I smiled and pinched my nose as I leapt off the rock into the crystal-clear water below.

Four days and 100 miles later, I arrived at Georgian Bay. High cottony clouds raced across the bright noonday sun. I set my paddle down and consulted my map for what seemed like the hundredth time this day. Georgian Bay is called “the bay of 10,000 islands.” As I looked around at the nearly identical, bus-sized islands that surrounded me in every direction, I guessed that to be a very conservative estimate. The Islands were only 20 to 30 feet apart, and were so close and braided that I could easily imagine going around and around unless I watched my compass. I could see 15 islands from this one spot, although I couldn’t tell which one was which, because of the way they overlapped. Only 15 feet to my left, one of the larger islands bore a stand of 80-foot-tall white pines. Devoid of limbs for the first 20 feet, the trees leaned gracefully toward the northern shore, as if trying to escape the perpetual breeze blowing off the lake. Ahead of me, an otter scurried along the smooth, chocolate-colored granite of a treeless island and slid into the water.

After a day of wandering among the islands, enjoying their abundance of wildlife-ducks, eagles, black bears, muskrats and otters – I pulled my kayak onto one of the rounded islands for the night. I pitched my tent in the only flat spot I could find. The area was covered with blueberry bushes at the peak of ripeness. I had to rake away handfuls of berries in order to set up my tent. I could see the green fabric of the tent becoming stained in large blue splotches like camouflage. As I tended my dinner cooking on the camp stove, it seemed as if all of the animals and birds in the area had come out to the islands to take advantage of this seasonal bounty of berries.

The next day, the islands thinned as I paddled farther away from shore. This made for faster paddling and easier navigation, but it wasn’t nearly as interesting. I looked at my watch. It was already the seventeenth of August, and the days were growing shorter, the winds stronger. I still had 125 miles of paddling left before I switched back to biking. I folded my map and tucked it away under my spray skirt. As long as I kept heading east, I would get there eventually. I grabbed a handful of blueberries from the pan between my knees and reluctantly turned my kayak and wound my way out toward the open lake.

Seven days later, 48 days and 950 miles after beginning my paddle, I paused to pull my worn felt hat down tight, and lowered my head into the wind and blowing rain. I squinted across the whitecaps toward the sandy shoreline a half mile in the distance. My wife was waiting for me on that beach with hot food. Despite how much I was looking forward to the comforts of home, I felt a little emptiness inside. I had several weeks of biking left, but completing the kayaking portion was the dream I had been chasing and, now that I had caught it, I felt a sense of emptiness, a void I could fill only with another dream. I dug my paddle in and headed for shore.