You know those stories where sea kayakers describe landing spots using phrases like “waves sweeping smoothly up a gently sloping white sand beach”? That never happens to me.

My paddling trips always seem to skirt gnarly coasts where the rubble on the beach is still several geologic epochs short of “sand.” Perhaps that’s because my main stomping grounds are in the Sea of Cortéz—a toddler, as coasts go. With Baja California still in the process of being ripped asunder from the Mexican mainland, the shore here is rarely described as “smooth” or “gentle.”

If there is any sand, it’s usually just a tenuous strip between water and the barely cooled volcanic substrate under the desert scrub.

For this reason, I’ve always steered away from sandals and wetsuit booties toward more substantial paddling footwear. I want something that will protect my feet during a landing but also while scouting camp sites and just looking around spontaneously.

For years, I’ve worn a pair of U.K.-made Hunter Wellington boots during winter (to the delight of several groups of English paddling clients who believed that I might have the only Wellies in the world with cactus-spine scars).

During the hot months, I used to switch to cheap, high-top Keds, which worked great in terms of traction and abrasion protection above the anklebones, but not so great in that they held water and tended to rot quickly. Then someone invented water shoes, and my life got much easier.

Designed to Get Wet

Broadly speaking, a water shoe is simply a shoe designed to get wet. Most are constructed of neoprene or nylon mesh with synthetic leather reinforcement. With these materials, neoprene is warmer, but nylon dries more quickly.

Soles can range from stippled rubber to fairly stout lugs, and uppers can be low or high cut. (Stout lugs offer better protection on rough surfaces and more support for walking but are clunkier in the boat. High uppers are warmer and protect your ankle bones.)

Some water shoes simply pull on, and others lace up and look from a distance like typical athletic shoes.

Rugged coasts aren’t the only reason to consider wearing water shoes. They are designed to hold up to the chafing of your heels or the sides of your feet against the hull of the kayak.

In my opinion, they offer firmer control of rudder pedals than any sandal. Some models offer fair protection against immersion hypothermia, whether worn alone or, even better, over a light pair of insulating booties.

Virtually all are surefooted while you’re clambering over a wide variety of shoreline terrain, from Pacific Northwest logjams to Baja volcanoes.

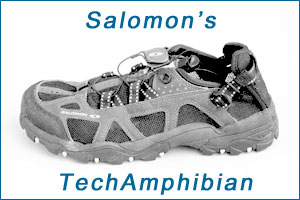

TechAmphibian $85

The Salomons might be the best hot-weather kayaking shoes I’ve used. The entire upper is constructed of nylon mesh just tight enough to keep out sand grains that would be large enough to chafe, with synthetic leather reinforcements.

The result is an airy shoe that never feels stuffy and empties itself of water instantly. The heel strap makes it easy to adjust the fit of the shoe to wear over neoprene booties, making the TechAmphibians viable as a cold-water choice too.

The sole is broad, shallow-lugged and quite stiff, very similar to that on a standard light hiking shoe. It has an expanded vinyl acetate (EVA) midsole for shock absorption and a thermoplastic footplate for protection and rigidity. As a result, it offered the best performance in the group of shoes reviewed, for scrambling over coquina reefs, sharp-edged rocks and other desert terrain.

The uppers, however, are susceptible to thorns and aren’t high enough to protect your ankle bones from scrapes.

In the boat, they worked just fine too. My only reservation has to do with the small diameter Kevlar laces, which, while they make tensioning the shoes a cinch, could theoretically snag on a rudder pedal or something during a wet exit.

I say theoretically because, try as I did, I couldn’t make such a thing happen. But you know how that goes—the car never makes that noise when your mechanic drives it.

Still, it’s a very small concern. If you worry about such things, leave the heel strap loose, and you can easily slide out of the shoes. I would also cut off the Velcro tabs at the ends of the laces and singe the ends to prevent them from fraying.

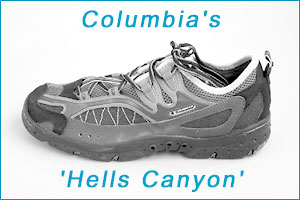

COLUMBIA Hell’s Canyon $70

The Hell’s Canyon shoes wouldn’t draw a second glance if you wore them shopping or to the health club—they look just like a generic athletic shoe. The upper doesn’t drain as quickly as the Salomon shoes (hold the latter sideways up to the light, and you can see right through them; not so the Columbias), but mesh and drains in the forefoot pump water out within a few yards of walking. Likewise, the sole of the Hell’s Canyon doesn’t have the same protection plate under the arch as the Salomon.

On the other hand, its ribbed carbon rubber sole sticks better to wet rock, and an EVA mid-sole cushions your stride on smooth surfaces. There’s a row of thick stitching around the perimeter of the sole, the function of which I’m unclear about since the sole is glued to the upper, but the stitching looks vulnerable to abrasion, so let’s hope it’s just for fashion. A bead of seam sealer would help protect it.

The Hell’s Canyon was among the most comfortable shoes in the boat, due in part to the supportive nylon and synthetic nubuck upper. That, combined with the sticky sole, seemed to give me a little more control over the rudder pedals than any of the other shoes.

They were also noticeably warmer than the Salomons, which I expected, considering their solid upper, and when paired with neoprene socks felt very warm indeed. Combined with their ability to serve as perfectly normal-feeling walking shoes, this made Columbia’s Hell’s Canyon one of my top choices as an all-around boating shoe. Just tuck in those lace ends—they have a lot of extra length to them.

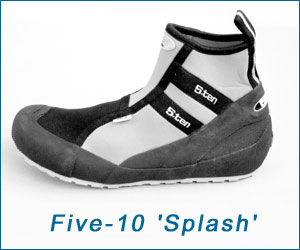

FIVE TEN Splash $49

The Splash is an update of (and a significant improvement on) the already excellent Five Ten Hydraulic. Like its predecessor, the Splash is a high-topped, pull-on shoe, but its upper is made from 3mm neoprene instead of the Hydraulic’s 4mm.

Nevertheless, it’s still a warm shoe and a good choice for cold-weather wear. With a neoprene sock, it would be even warmer. That said, the Splash shoes never became clammy during my trial runs in mild conditions. And the bright red of the sample provided brought back fond memories of my old Keds.

The soles are a non-marking gray rubber with sort of an octopus sucker arrangement minus the sucker holes. Whatever the structure, the result is that they stick just like an octopus to wet rocks.

The forefoot is flexible enough to allow your feet to mold around rocks, but there’s noticeably more stiffness under the heel and arch than in the Hydraulic to help guard against sharp-edged rocks.

The best addition to the Splash is a whole bunch of vulcanized reinforcing rubber in high-wear spots, with a double thickness of it around the heel and toe box. These shoes should be immune to abrasion, whether from rough fiberglass inside the kayak or rough rocks outside of it. The perfectly cupped heel pocket will make long paddling days a numbness-free cinch.

The Five Tens wouldn’t be as suitable for long hikes as the Salomons or the Teva Rodiums (see following Teva reviews), but for messing about in boats, they’re unbeatable.

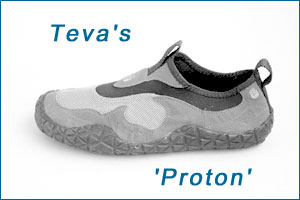

TEVA Proton $35

The Protons, which are available in both men’s and women’s sizes, are the climbing slippers of the water shoe world: a low-cut, slip-on wisp of a shoe for those who would really rather go barefoot but need a little protection and traction.

The crosshatched, thin rubber sole sticks well to wet or dry surfaces, although it offers scant impact protection or armoring against protruding rock edges. However, it does wrap just high enough on the upper to prevent chafe on your heel and the side of your foot in the boat.

I worry about the many lines of stitching joining the synthetic nubuck and nylon mesh in the upper, but I didn’t notice any incipient problems, such as chafe, during testing.

Since the Protons add very little bulk to your foot, they’d be ideal in tight quarters like a skinny, Greenland-style kayak. They’re great in hot weather, but if they were sized so a neoprene sock would fit inside, they would work in chilly conditions, too.

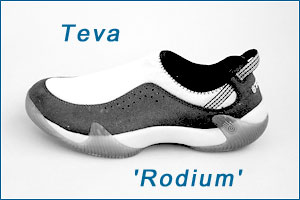

Rodium S.O. $69.95

Also from Teva, the Rodiums look more like water clogs than water shoes. They’re big and blocky and the heaviest in the review by a couple of ounces, despite a low-cut, slip-on upper. It’s all due to the sole, which is thick and stiff and makes the Rodiums the most comfortable walking shoe reviewed (except perhaps for the Salomons).

A shock pad in the heel and a synthetic shank across the arch isolate your feet from virtually any ground nastiness or from sharp rudder pedal edges. The sole itself is only lightly scored, thus its traction on wet and dry rock is excellent, but on sand-covered rock, it felt much less secure than a sole with deep lugs.

In the kayak, the Rodium’s thick heel cup made for notably comfortable long passages, and there were no protruding interior seams to annoy. After immersion, two grommets in the bottom of the synthetic leather and nylon upper drain the bilges dry within a few steps. For a low-cut shoe, these seemed very warm, but the knit nylon mesh took a long time to dry.

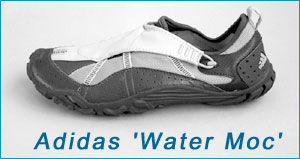

ADIDAS Water Moc $65

The stylish Water Mocs have the look of a track racing shoe, with red accents and a bright, coated stretch-fabric lace cover that snaps over two plastic hooks.

The cover is supposed to protect the laces from snagging, but it actually seems that it is itself something that can snag. In fact, one cover developed a small tear, suggesting that it might have snagged on something during testing.

Lacing aside, the Water Mocs performed well. The uppers are a blend of perforated synthetic leather and a very fine mesh that kept out everything except silty sand but drained in a second.

Three small, screened holes so far under the arch as to be in the sole, and several more under the heel, actively pump out any remaining water. Of course, with all the mesh and holes, the Water Mocs ventilate fabulously and are comfortable in hot weather.

If you buy them sized to give you a slightly loose fit, you can have room inside for neoprene socks in cold weather.

The sole is a thin rubber, but with fairly aggressive lugs, so traction was good on almost anything. An EVA mid-sole provides surprising cushioning for the thickness but not much resistance to gouging edges.

There’s a smidgen of arch support, so walking on smooth surfaces was comfortable for long distances. Although I think Adidas could remove the lace cover, and perhaps even replace the laces with a Velcro strap, the Water Moc is a good kayaking shoe.

Hydrology $65

You’ve heard the old joke about screen doors on a submarine?

It popped into my head when I examined the second Adidas water shoe reviewed, which sports a half-dozen comparatively huge metal screen ports right in the bottom of the sole.

Like screen doors on a submarine, they let water in or out with equal facility. I thought they would clog quickly in sand, but that never happened. Only when I took them on a fresh-water excursion to a lake with muddy banks did they plug tight—after pumping a bunch of silt inside.

But for most seashore substrates—sand, cobble or rock—they worked just fine, and made the Hydrology one of the quickest draining shoes I tried.

Otherwise, they look and perform very similarly to the Water Mocs, except that the lace cover is sewn all the way up one side of the shoe, so it can’t snag in that direction at least (a big improvement from the Water Mocs).

The rubber reinforcing on the outside of the sole is also a little thicker, and the perforated synthetic nubuck uppers protect whatever part of your foot they cover (which doesn’t extend above the ankle bone) from abrasion. In fact, especially in light of their reasonable price, these shoes are a very good choice.

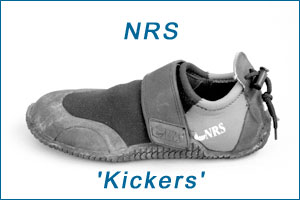

NORTHWEST RIVER SUPPLIES (NRS) Kickers $31.95

A draw cord around the low ankle opening plus a fat Velcro instep strap means there’s no way the Kickers will come off unintentionally—nice if you play in surf or other situations where capsizes and thrashing wet exits are frequent. The flexible rubber sole wraps around the 2mm neoprene uppers at the heel, instep and toe to protect the foot and add abrasion resistance.

NRS built a thin plastic shim into the mid-sole of the Kickers, which helps a bit when hopping over jagged rocks, but there’s still very little protection in such circumstances. Best to keep the speed down and let the sticky soles cling where you put them. If you paddle along shores where slick rocks are the norm, consider the optional felt soles, which act like the soles on fly-fishing waders to grip right through slime.

The Kickers have a business-like appearance, as if fashion had been well below function on the design brief. And that’s just how they performed. I’d rate these as perfect for high-energy paddling, where a bit of warmth, protection and traction and a lot of security are important.

Normally somewhat of a marketing skeptic, I admit to being impressed at how well manufacturers have addressed the needs of boaters with these shoes. I was also pleased at the range of function and features, which should satisfy paddlers from Beringia to Baja. I know I’ll find a use for them—at least until I stumble across one of those gentle, white sand beaches.

DRY FEET, WARM HEART: Waterproof Socks

by Jonathan Hanson

An interesting alternative to the traditional means of keeping your feet warm while paddling—some sort of neoprene sock or bootie, which stays warm when wet—is to keep them dry and warm, by wearing waterproof socks. I tried out a couple of varieties with the water shoes from this review.

The first thing I learned was that only tall stretchy socks work for kayaking. I tried a pair of Gore-Tex oversock, designed for hikers to wear over regular socks.

They use a non-stretch nylon outer fabric with stretch panel in front and a Gore-Tex laminate inside, lined with tricot. The top was only about 10 inches high and kept my feet dry as long as the water stayed below the tops, which just have a loose-fitting hem—nothing to prevent water entry.

Once dunked, I was left with soaked feet and socks full of water that wouldn’t drain. Gore-Tex is permeable to water as a vapor, not as a liquid. These might work great under hiking boots for fording shallow streams, but they’re not for situations where a full dunking is not uncommon.

SEALSKINZ

The stretchy socks from Sealskinz, on the other hand, worked well even when fully immersed. Their WaterBlocker Socks (15″ high) and All-Season Socks (11″ high) are both very comfortable worn over bare feet because they incorporate a soft lining of wicking material under a waterproof, breathable membrane. The stretch construction of both SealSkinz socks provided a snug fit and prevented much water from getting into either model.

I tried each pair under all the paddling shoes I tested and never found them unpleasant or clammy in 70-75° weather and 65° water. The difference between the two is that the WaterBlocker socks have a cuff designed to keep out most water even when completely immersed.

And it worked: I waded around in knee-deep water for 15 minutes and got barely a drop or two inside the sock. One swimming session produced the same results. But here’s the key: Even when I deliberately pulled the cuff open and let them fill with water, it quickly warmed to body temperature, and I stayed as comfortable as I would have with a thin neoprene sock.

I was sold. However, because the WaterBlocker cuff was no less comfortable than the cuffs on the All-Season version, I’d give them my highest recommendation.

I still need to try them in hot weather, when they might be too stuffy. But for cool or cold conditions, worn alone in the former or under a standard neoprene bootie in the latter, I think these waterproof socks could be a valuable extra line of defense against immersion hypothermia and an excellent way to keep your feet more comfortable at other times.

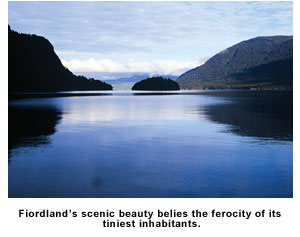

Not that I really felt endangered. With only my hands exposed, I was just impressed that Mother Nature could deliver shock and awe in such small packages. Impressed and annoyed, but mostly itchy. That’s the trouble with fine weather in Fiordland—the sand flies love it too. They especially love fine weather at dusk, in damp, cool tidal creek beds where there is no wind, and Lumaluma Creek, at the head of Fiordland’s Edwardson Sound, in late summer is just that—sand-fly paradise.

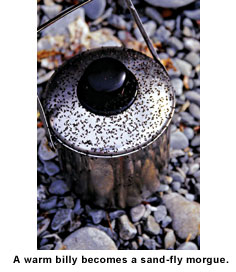

Not that I really felt endangered. With only my hands exposed, I was just impressed that Mother Nature could deliver shock and awe in such small packages. Impressed and annoyed, but mostly itchy. That’s the trouble with fine weather in Fiordland—the sand flies love it too. They especially love fine weather at dusk, in damp, cool tidal creek beds where there is no wind, and Lumaluma Creek, at the head of Fiordland’s Edwardson Sound, in late summer is just that—sand-fly paradise. Cooking dinner is a trial, and eating it is equally challenging. While cooking, you can wear a mesh veil and constantly wave your exposed hands around. But eating necessitates removing your veil and exposing your face and neck to the onslaught.

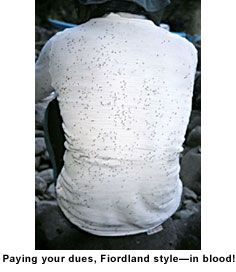

Cooking dinner is a trial, and eating it is equally challenging. While cooking, you can wear a mesh veil and constantly wave your exposed hands around. But eating necessitates removing your veil and exposing your face and neck to the onslaught. escaping. There is no bug-free option to be selected by ticking the box on a booking form. You pay your dues in blood when you visit Fiordland—it’s part of the deal. Just as you can’t experience a tropical rainforest without sitting out a wet-season thunderstorm, so it is with Fiord-land’s sand flies. They’re just as much part of our wilderness heritage as the pristine forest, the imposing mountains and the sheltered inlets. Our paddling paradise, too easily attained, would be devalued without them. And besides, as Maori legend suggests, paradise is intended only for the afterlife.

escaping. There is no bug-free option to be selected by ticking the box on a booking form. You pay your dues in blood when you visit Fiordland—it’s part of the deal. Just as you can’t experience a tropical rainforest without sitting out a wet-season thunderstorm, so it is with Fiord-land’s sand flies. They’re just as much part of our wilderness heritage as the pristine forest, the imposing mountains and the sheltered inlets. Our paddling paradise, too easily attained, would be devalued without them. And besides, as Maori legend suggests, paradise is intended only for the afterlife. On Saturday, May 26, 2001 , 51-year-old Robert Beauvais participated in a sea-kayaking course for beginning paddlers—a six-hour class listed as Essential Skills I, run by a New England–based kayak school. The participants included four students and Carla, a British Canoe Union (BCU)–trained (Four Star) instructor. (Names of the staff and other students have been changed.)

On Saturday, May 26, 2001 , 51-year-old Robert Beauvais participated in a sea-kayaking course for beginning paddlers—a six-hour class listed as Essential Skills I, run by a New England–based kayak school. The participants included four students and Carla, a British Canoe Union (BCU)–trained (Four Star) instructor. (Names of the staff and other students have been changed.)