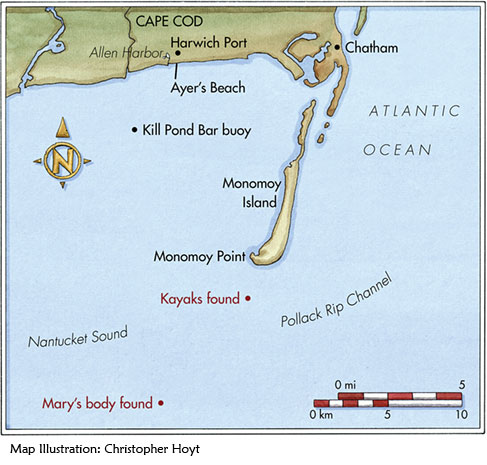

On the Sunday afternoon of Columbus Day weekend in 2003, Mary Jagoda, 19, and Sarah Aronoff, 20, kayaked into a thick October fog from Ayer’s Beach in Harwich Port, Massachusetts. Before going out into Nantucket Sound, they told their boyfriends that they were going to paddle around for 10 minutes. When they hadn’t returned 40 minutes later, their boyfriends called for assistance. Two days later, the Coast Guard found Mary’s body floating in Pollack Rip, several miles off Monomoy Island. Sarah’s body was never recovered.

I was kayaking in the sound within a few hundred yards of them at the precise time they left the beach, but I couldn’t see farther than a hundred feet in those conditions. That wasn’t unusual. Anyone who has kayaked in New England for any length of time will have stories about fog. It’s unavoidable, and the farther north you go, the more fog you’ll encounter.

There must be a measure of luck in being handed the good fortune to come home wiser where others have perished. In part, this is the story of my passage from a foolish neophyte to a kayaker who is at least knowledgeable of the risks. I have to confess to having “backed into” sea kayaking, and in retrospect, I took many risks that I shouldn’t have taken while using my first kayak to go fly-fishing. I often ended up with dinner on my stringer, but I found that more and more, I just enjoyed the paddling.

First Paddle in Fog

In the summer of 2002, the year before the drowning deaths, my wife and I rented a house on Little Cranberry Island. The island is several miles off the coast of Maine, and the only way to get to it is by mail boat or water taxi. On one afternoon, the house was full of guests, and I was climbing the walls, looking for an escape. I rented a recreational kayak from an islander who had a small fleet of kayaks. She supplied a life jacket and paddle with the kayak but was out of compasses. She swore she’d get new ones in a couple of days, but I’d have to do without for the time being.

My circumnavigation of Little Cranberry involved crossing a narrow neck of land that connected the island to nearby Baker Island. The hourglass-shaped constriction can uncover at an extreme low tide and only allows a cautious passage for shallow-draft boats at high tide.

It was quite sunny when I started out, but when I began crossing the exposed southern bay of Little Cranberry, a thick sea fog suddenly rolled in. It was the first time I was fogged in on the sea without a compass. I was entranced by the mist blurring, then obscuring all landmarks, but I had to improvise quickly to keep from paddling out to the open ocean. I needed something to keep me pointed in the right direction, so I quickly took note of the orientation of wind, waves and swells relative to the last glimpses I’d had of the land. Within minutes, I was completely enveloped and could only make out the waves, swells and an occasional lobster buoy.

I could hear the waves crashing on the rocky beach a mile away. I could hear each wave crash, followed by the sound of rocks grinding together as the water receded. Landing there would’ve been foolhardy, but the noise gave me an auditory reference for direction.

As I approached the gap between Little Cranberry and Baker Island, I could hear the breakers in front of me. The lobstermen set traps only so close to the rocks connecting the two islands, and at a certain point, I passed the safe zone of lobster buoys into shallow water. I made a slight detour around a shelf with waves breaking over it, then saw some rocks to my left. Somehow, I slowly made my way through the maze by pushing ahead into the calmest water I could find, always trying to get past the next 50 feet. Beyond that, I couldn’t see a thing.

I approached a zone full of ledges, and the fog parted long enough for me to make a passage through waves breaking there. I noted the wind and swell directions before getting hemmed in again. I followed the line of lobster buoys around the island. When the wind dropped, I saw that the buoys had little wakes behind them and used them to follow the direction of the flood current back to the harbor.

Back in the harbor, I saw a couple who had jet-skied to Cranberry. I noticed that they were both wearing wetsuits. It dawned on me that my outing was fraught with risks. The water temperature was 50˚F, but I was wearing only cotton, and I was sitting on, not wearing, my PFD. I had no compass and hadn’t listened to the weather report. When I got back home to Boston, the first order of business was to buy a wetsuit and a compass.

Columbus Day

The following year, on that unfortunate Columbus Day weekend, my family and I were staying on the beach in Harwich Port on Nantucket Sound. The water temperature had started dropping into the mid-50s, and it was my last chance to fish for striped bass. On Sunday at noon, I put on my wetsuit, launched from the beach heading southwest past the entrance to Allen Harbor, and paddled out to fish for stripers. The sound was shrouded in thick fog, and visibility was perhaps 100 feet. I only saw one other boat out on the water—a small outboard carrying three guys. They waved to me then vanished into the fog. As I rounded the light off the point at Allen Harbor, I tried to stay in sight of land, but it disappeared from time to time. Noises were muffled and deceiving.

I’d promised to take my kids out to the movies that afternoon and checked my watch. I had just enough time to get back to the beach. This jarred me out of my reverie, and I headed back to the put-in. I came ashore with the mist blowing over the water.

Overnight, the wind picked up from the north, and by Monday morning, it had blown the fog away to reveal clear blue skies. I went out paddling and saw the harbormaster’s boat near the mouth of Allen Harbor. As I got close to it, its lights flashed and its horn sounded.

The guy at the helm asked me, “Have you seen two girls in kayaks?” I said, “Nope, I haven’t seen anyone on the water this morning; when did they go out?”

“They left Ayer’s Beach yesterday at three in the afternoon in two plastic kayaks. They’ve had the Coast Guard and everyone out in helicopters and boats searching for them all night long.”

I had been within a quarter of a mile of Ayer’s Beach at that precise time on Sunday, chasing stripers and enjoying the fog.

“I’ll keep my eyes out and call if I see anything.”

At that moment, the Coast Guard came crackling over the -harbormaster’s VHF radio. It was one of the search -helicopters.

“Woods Hole, Chopper Three, we’ve found two kayaks in Pollack Rip, will launch a diver, over.”

“Chopper Three, Woods Hole, we copy, over.” I could hear the helicopter noise over the radio.

The guy in the boat immediately got distracted. We parted company, and I paddled home. I got on my laptop and checked the Cape Cod Times website. In the article I read there, a witness had indicated that they’d seen one girl paddle along the shore, the other out into the sound. Mary’s father was quoted saying that she had taken kayaking lessons, and there was no way that she could have drowned. He speculated that since the kayaks were found near Monomoy Island, they surely had landed and were walking for help. Dogs were dispatched to the island, and people were searching the beaches and dunes for fresh footprints. I had a sinking feeling he was fighting against the inevitable bad news.

All afternoon, I sat on the porch overlooking Nantucket Sound. It was warm, and the sky was clear blue, with only traces of high cirrus clouds. I watched the Coast Guard helicopter flying a search pattern back and forth across the sound. It would swing close to land, turn around and nearly disappear over the horizon, then return again. It was agonizing to watch. I had written an email to a friend on Sunday night saying, “I felt so alive out on the ocean.” Those words were now hard to swallow.

The next day, Tuesday, I read in the Boston Globe that the Coast Guard found the kayaks over eight miles away from where the girls had launched. They later found Mary’s body. She hadn’t been wearing a life jacket. The search continued, but Sarah was never found. Reading about Mary and Sarah, I felt guilty about the exhilaration I’d experienced that day. I wondered if things could have been only slightly different, I might have run into them in the fog, and I could have helped them find the shore.

What May Have Happened

We know very little about what took place that Sunday. The girls only wore bathing suits and T-shirts. They didn’t have a compass or life jackets. The kayaks were small and not very seaworthy; they were found tied together with a bungee cord.

We can only guess what happened. Mary and Sarah went out to have some fun. The fog was already quite thick when they launched, and they lost sight of shore quickly. It’s not likely that they noted the wind direction or other natural signs that would have helped them orient themselves. They were still together and may have paddled for a while, with panic rising. The fact that their kayaks were found about eight miles from where they launched suggests that they had headed east—out to sea—in the fog.

There’s a whistle buoy at a place called Kill Pond Bar about two miles offshore. When the wind is blowing from the southeast, the sound from the buoy carries very far inland. The girls may have heard the sound and, thinking it was a harbor entrance or something close to shore, followed the sound out toward the buoy. I was out at the same time in the same area, and if I did hear the buoy, I didn’t really think about it. I’ve heard it so often that it’s just part of the background.

Their T-shirts must have been soaked from the spray kicked up by the wind. At some point, the wind dropped off, but they got colder and colder. They started to shiver, and they may have tied their boats together when one of them became incapacitated by cold. That night, at 11:45 P.M., the fog cleared and the wind shifted to the northwest. The wind started to pick up, and waves began to build offshore.

Weakened and dazed by hypothermia, they eventually would have lapsed into unconsciousness and fallen from the kayaks. The flood tide would have carried their bodies southeastward, and the kayaks would also have been pushed that way by the wind. Mary’s body may have been swept through Pollack Rip at least twice in the cycle of tides between Sunday and the recovery on Tuesday.