In late January 2000, my buddy Dave Stibbe and I set out on a paddling adventure in Southeast Asia.

Our starting point was Phuket, on the north end of Thailand’s west coast. Our planned finish was Bali, Indonesia-2,800 kilometres away. We had a three-month window to complete our trip, and agreed beforehand to just go with the flow. We were equipped with a reliable folding double kayak and two cases of Spam, so we were feeling pretty confident.

Each of us had a wealth of experience: I had paddled 9,000 kilometres across Canada in 1995, and Dave had 18 years of experience as a guide in the outdoors. We had already spent several weeks on dry-land adventures, after which we had paddled the 300-kilometre Thai coast and the whitewater Selangor River in Malaysia.

Each of us had a wealth of experience: I had paddled 9,000 kilometres across Canada in 1995, and Dave had 18 years of experience as a guide in the outdoors. We had already spent several weeks on dry-land adventures, after which we had paddled the 300-kilometre Thai coast and the whitewater Selangor River in Malaysia.

While I was on the river, I had come down with a nasty systemic blood infection through a cut on my elbow, and we had spent a couple of weeks in the Malay capital of Kuala Lumpur, waiting for me to get out of the hospital. A bit of surgery and ’round-the-clock IV drip antibiotics cleared it up.

From there, we traveled inland through Sumatra and Java, eventually ending up in the city of Jakarta. After a few days in the crazy, bustling city of 17 million, we were ready to head out onto the water again for some peace and quiet, and a little adventure. We made plans to paddle 1,200 kilometres of the Indian Ocean along the exposed south coast of Java, to Bali.

This would be the last leg of our journey.

From Jakarta, Dave and I traveled by bus and ojeck (mini-bus) to the fishing village of Sumur, on the west coast of Java. We settled into a basic losmen (guesthouse) for the night; it catered to local Indonesians, and was the only place in town for us to stay.

A single dim light bulb hung in our musty room that was furnished with two worn cots. A well outside provided water. The central toilet was a hole in the ground that you squatted over and flushed by scooping water into it from a basin. Par for the course and all we could expect for $2.50 U.S. per night (for both of us). Because of tumultuous national politics over the past couple of years, Indonesia has been in a tourism slump.

The proprietor of the losmen told us (with help from our phrasebook) that we were the first “white people” to stay there this year. In the morning, Dave and I carried our gear down the dusty dirt road that served as Sumur’s main street. We passed by food stands overflowing with bananas, coconuts, papayas, cigarettes and  shiny cellophane-wrapped treats. People sat in front of their simple wooden and corrugated tin shacks, smiling and saying, “Hallo, mister!” to us as we passed by.

shiny cellophane-wrapped treats. People sat in front of their simple wooden and corrugated tin shacks, smiling and saying, “Hallo, mister!” to us as we passed by.

“Hallo, mister” is the one English phrase that every Indonesian man, woman, and child seems to know and use quite liberally. Two hundred yards from the losmen, the road ended at a beach lined with a dozen fishing boats. They ranged from 15 to 25 feet long, with rotted planked hulls, rusty diesel-powered outboards or inboards and black oil-stained wooden decks. A small, covered captain’s cockpit popped up at the front before their deep, upswept bows.

A few puffy clouds lounged in the backotherwise brilliant blue sky. With an entourage of a couple of dozen villagers in tow, we picked an open spot between two of the boats and set about our construction project. Dave began stashing our gear in dry bags while I assembled the kayak.

Word travels fast in a small town like Sumur, so a hundred or so of the locals crowded in tight to see the kayak take shape, giving me only inches of breathing room. When I accidentally poked some of the kids with kayak frame parts, the villagers laughed. They followed my every move, pointing and giggling as if they were watching a major sporting event. “Ooohs” and “aaahs” reverberated throughout the audience as our kayak steadily came into shape.

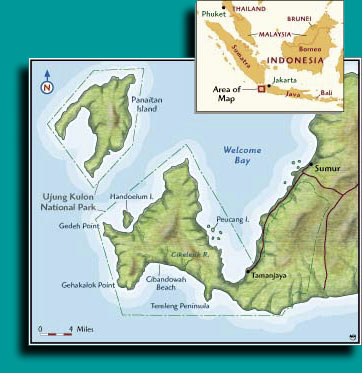

Gentle one-foot rollers splashed against the Hypalon hull of the kayak. Ujung Kulon National Park is made up of 800 square kilometers of roadless wilderness on a peninsula on the southwest tip of Java. It was declared a World Heritage Site in 1991, and achieved its park status in 1992. It’s bordered by wave-thrashed volcanic cliffs and jungle-covered volcanoes to the west; alligator and crocodile-rich swamps and mangroves to the north; endless uninhabited stretches of surf-pounded beach to the south; and unique flora and fauna-including endangered Javan rhinos and leopards-in the jungle of the east.

We followed the east coast of Selamat Datang Bay for 15 kilometres until our lunch stop. Turquoise waters lapped gently onto the golden-sand shores of the bay. Children played in the shallows, and fishermen casting hand nets pulled in the shimmering, struggling bounty of the Indian Ocean. We had lunch beside the bleached wooden skeleton of a fishing vessel on the beach, and looked west, across to the park.

The middle of the bay was far less protected than the shore; whitecaps danced on the water all the way across. After lunch, we crossed over the bay through one-meter swells, the ocean spray coating our boat and bodies as the sun sparkled off the ocean and the wind rippled across the water.

We arrived at Peucang Island at five in the evening after a 30-kilometre day, and set up camp at a ranger station, the only spot clear of swamp and mangrove in this low-lying area of the park. We erected our tent in a rough grass field sprinkled with coconut trees.

A simple wooden structure with a map of the park posted by the doorway served as the ranger’s cabin, while an empty, three-room motel-style plywood building stood across from it at the other end of the field. Launching the next morning, we paddled in heavy monsoon rains and wind, in swells up to three metres high. There was no place to land on this flat, northern-exposed, rock-rimmed swamp for 20 kilometres.

Broken volcanic rock blocked any chance of landing. We ate lunch while paddling, and arrived at 6:00 p.m. at Handoelum Island, soaked to the bone. Over a hearty Spam-and-noodle dinner, Dave and I shared our concerns about the relatively slow speed of the kayak and its open design-with no bulkheads, and a canoe-style spray deck-on big Indian Ocean water.

Our main concern was how the kayak would handle during the really big surf landings that we would have to tackle on the exposed south coast of Java. The following morning, March 22, we tied all of our gear into the kayak and headed southwest. We planned to paddle 25 kilometers around the notorious Gedeh and Gehakalok points.

Between these two points are 12 kilometres of 50- to 200-meter cliffs that drop off from the emerald-forest-covered volcanic peaks on the western tip of Ujung Kulon. Exposed to the full might of the open Indian Ocean, this section has laid claim to many a fishing boat. Quiet, focused, and a bit nervous, we ventured into the chaos around Gedeh Point.

Massive, house-sized swells (five to eight metres high) crashed into the cliff faces with incredible force. The resulting rebound waves came back and smashed into the incoming rollers. We were being hit from both sides with these giant colliding waves, making for tricky paddling. The ocean’s color transformed from turquoise to a dark blue, indicating a change to deep water and open-ocean conditions.

The kayak remained stable as we moved away from the point. As we crested a swell, we spotted a tanker out on the open water, then it disappeared as we entered the canyon-like trough of the wave. After we rounded Gehekalok Point, we were getting quite used to the roller coaster ride through the swells, and had lunch aboard the kayak.

Nearby, the ocean was hammering a small rock island, shooting 10-metre vertical sprays of water. Only 20 metres from the action, I pulled the camera out from under the deck for a shot, when both Dave and I heard a loud roar coming from behind us. We turned to see a steep six- to seven-metre rogue wave breaking and heading for us. Up to this point, the swells had been clean, but in that instant, in the trough of the wave that created the break, I spotted a shallow reef.

Dave shouted, “Put the camera away! Put the camera away! Paddle! Paddle! Paddle!” I hurriedly jammed the camera under the deck and paddled like mad. Pumped full of adrenaline, we made that kayak move as never before, narrowly evading the oncoming wave that would have crushed us against the lava cliffs. We were instantly filled with pure joy and elation; we laughed giddily, and whooped in relief at escaping the close call. We aimed toward Cibandowah Beach, a deserted 18-kilometre stretch of white sand rimmed by dark, low-lying jungle.

It was late afternoon and we had to land somewhere along this shore, since beyond the beach was another long stretch of rocky cliffs. We were ushered into shore by six- and seven-meter swells, indicating that the shore break would be nothing to sneeze at.

As we approached, the waves along the shore were popping straight up like rooster tails when they hit the beach. This meant it was a steep beach with a short, abrupt surf zone. Time to check out how the old kayak, and we, would do in some seriously trashy water.

Within 40 meters of shore, the break was big, steep, fast and powerful. I scanned up and down the barren coastline, but the story was the same everywhere. I was ready to go for it. As we entered the surf zone, I knew we were in trouble. The first couple of five- and six-metre rollers steepened and broke just after passing under us. The next big roller approached and opened its gaping mouth at us. I shouted, “We’re going down!” “Not yet!” Dave replied. We balanced precariously on its tip as it broke. Looking down the face of the wave, I gauged the distance to be roughly that of a two-story building. It didn’t take us and, in the brief reprieve, we glimpsed a stretch of flat water leading to the shore.

We paddled hard for land, trying to work through the strong suck-back off the beach before the next wave hit. Unfortunately, it was to no avail. A six-metre roller came quickly behind us and grabbed us. For a split second, it held the kayak completely vertical before body slamming us face-first into the surf. Our 600- pound kayak (with us and our gear) was tossed like a toothpick.

Underwater, I was violently jettisoned out of the kayak by the force of the blow. I popped up to be hit by yet another wave that shot me in toward shore.

I swam after our capsized kayak and grabbed it, then fought to get the water-filled boat to shore. I noticed immediately that its hull buckled sickeningly in the center.

After struggling with the strong ebb and flow of the surf zone, I got the boat partly on shore. I turned to see Dave knee-deep in the shallows, thrashing around, trying to collect the smaller “yard-sale” items that had not been tied into the boat. He flashed a smile at me, indicating that he was OK. I helped him, and we eventually got everything high and dry.

The casualties: two lost pairs of sunglasses-and our kayak. I inspected our craft and found that the two main center ribs, the side supports, the coaming, all of the bow pieces, the metal rudder fitting and the rudder were broken clean through: eleven parts in all completely trashed. About half of the frame was broken, and impossible for us to field repair.

The casualties: two lost pairs of sunglasses-and our kayak. I inspected our craft and found that the two main center ribs, the side supports, the coaming, all of the bow pieces, the metal rudder fitting and the rudder were broken clean through: eleven parts in all completely trashed. About half of the frame was broken, and impossible for us to field repair.

It would be unthinkable to paddle the kayak in this condition, especially on the Indian Ocean. It would act like a slinky for a while, until it broke apart due to stress on the unbroken frame parts. We were in the only uninhabited, roadless area of Java, in the farthest corner of Ujung Kulon. The water had destroyed our map; we had only a macro map of Java to go by.

From my memory of the ranger maps and our macro map, we figured that we had at least 40 wilderness kilometres to cover with all of our gear to get to the first inhabited village. Dave and I packed our soaked gear and kayak into our two large duffel bags, the kayak skin bag, the frame bag, the rib bag, Dave’s backpack, and my large camera case. In all, we estimated the bags to be in the neighborhood of 300 pounds. I felt pretty good, actually.

This castaway gig was pretty cool. We were by ourselves in the wilderness, and had a mission: To get ourselves and our stuff out under our own power through unpredictable and unknown terrain. True adventure never really starts until you mess up really badly.

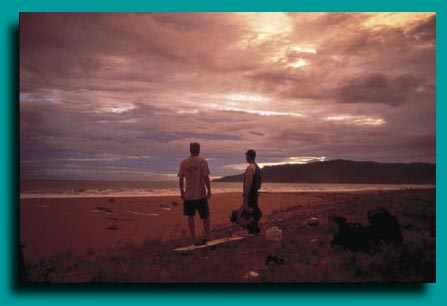

We fulfilled that criterion. After shuffling the gear about ten minutes down the beach, we set up our tent on top of a sand dune. It was getting dark, and a thin band of orange was the only light remaining on the horizon. On one side of our perch, we peered down into a firefly-lit, swampy jungle; on the other, we could see and hear the vastness and power of the surf that had crushed us. Our stove was soaked, but I dried it out and managed to get it going. It clogged up after a few minutes, so I took it apart to clean it.

With almost everything still wet, and camping on a sand dune, I clogged the stove even more. The more I fiddled, the worse it got. Spam time, once more! After being gnawed on by no-see-ums during dinner, we went to bed tired, damp and full of spiced ham, knowing that we had a big day ahead of us.

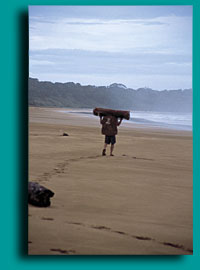

The next day was humid and, fortunately, overcast, with intermittent monsoon rains rolling in off the ocean to cool us. I shuttled 60- to 100-pound loads for ten minutes at a time, eastward down the beach. I’d then run back for the second load and haul it to where the first one was. I wore sandals, while Dave trudged at his own pace, barefoot.

The next day was humid and, fortunately, overcast, with intermittent monsoon rains rolling in off the ocean to cool us. I shuttled 60- to 100-pound loads for ten minutes at a time, eastward down the beach. I’d then run back for the second load and haul it to where the first one was. I wore sandals, while Dave trudged at his own pace, barefoot.

Dave likes the feel of sand on his bare feet and, despite my warning, thought he’d fare fine, even with the extra weight. “Uh, Dave, we’ve got a long way to go. You sure you want to go barefoot?” “I always walk barefoot in the sand. It feels good. Just like a foot massage.” “Suit yourself.” We needed to cover 15 kilometres along Cibandowah Beach before we entered the jungle. Once in the bush, we needed to find a trail that I recalled from the ranger map that led north to Selamat Datang Bay, where we had started.

Once at the bay, we would have to make our way up its eastern shore toward Sumur until we reached the village of Tamanjaya, where the first road out was. I cruised along in a Zen-like state, funneled forward along the beach by the ocean on my right side and the waving trees and vegetation of the jungle on my left. I thought of nothing much in particular except pushing forward. Black rain clouds rose off the ocean and soaked us, followed by a brief blaze of equatorial sun that dried us off.

We dodged between driftwood, discarded sandals, fishing nets, seaweed, shampoo bottles and anything else the sea had carried from far-off lands and deposited on the fine white sands of Ujung Kulon. I sang Village People and Abba songs to help keep myself occupied. We traveled seven kilometres in four hours, until we finally approached the Cikelesik River.

What we saw gave us pause: The river flowing out of the jungle was broad – about 20 metres wide, and the incoming tide rushed up the river like a rip. We had no choice. We forded the armpit-deep river with our heavy loads, digging our feet sideways into the sandy bottom to keep from being knocked over by the relentless force of the sea. My sandals sank deep into the sand as I strained to keep moving forward with my pack. After a prolonged struggle against the force of the flow, I finally emerged on the other side. As I turned around to check on Dave’s progress…..

I saw him lose his footing, and the surging ocean current swept him upstream into a lagoon next to the jungle.

I trudged up the channel toward the lagoon to offer my help. He struggled in the deep water to swim his pack to shore, swinging and splashing wildly with one arm, while keeping his other hand on the sinking pack. Once he got near the edge of the lagoon, he found his feet and sloshed onto the beach with a sheepish grin on his face. We were relieved to have made it across, in whatever fashion. We later found out from some rangers that the Cikelesik is home to a good-sized population of saltwater crocodiles-some reaching up to three metres in length.

Once he got near the edge of the lagoon, he found his feet and sloshed onto the beach with a sheepish grin on his face. We were relieved to have made it across, in whatever fashion. We later found out from some rangers that the Cikelesik is home to a good-sized population of saltwater crocodiles-some reaching up to three metres in length.

We needed to resupply our water, so I took out our water bottles and examined the brackish water. Unsure whether the water would be good, I sipped a mouthful, then disgustedly spit it out. We decided to follow the Cikelesik upstream through the jungle to see if we could find some fresh water higher up.

Grabbing our water container, we followed a crude trail into the dark bamboo, ficus and fern jungle. Water dripped off the funneling leaves of the tree ferns and cascaded like tiny waterfalls down to the muddy floor of the jungle. The still, muggy air of the tropical forest replaced the refreshing breeze off the ocean.

Betel nut trees, bamboo, bushes and vines grew in a dense thicket along the shore, hanging out over the river’s edge. We slipped and slid our way along the path, in and out of the trees and vines, our senses bombarded by everything around us.

After about 15 minutes of tramping, we came upon a small tributary. I walked down to the murky, still water and tasted it: more fresh than salt-good enough. As I stood knee-deep in the small river, slowly filling up the 10-litre container, raindrops peppered the still surface of the water.

After about 15 minutes of tramping, we came upon a small tributary. I walked down to the murky, still water and tasted it: more fresh than salt-good enough. As I stood knee-deep in the small river, slowly filling up the 10-litre container, raindrops peppered the still surface of the water.

Once the brown water had filled up our jug, I waded out of the stream and we made our way back to the beach along the slick trail. By now it was pouring. By 4:00 p.m., we had hauled our gear for ten hours and gotten to the end of the beach. We still had a couple of more hours of light, and planned to go through the jungle across the bottom of Tereleng Peninsula into Karong Ranjong Bay to camp.

I had become well acquainted with my burden. On one load I carried the kayak knapsack-style skin bag that also contained the spray deck, seats and PFDs. On top of this I threw the long, narrow frame bag that also contained our paddles, pumps and sail. The total was about 100 pounds. I walked in a crucifix-like position with my hands spread out to the sides above my head to support the frame.

My other burden was a 60- to 70-pound duffel bag that I carried backpack-style, with unpadded straps. Dave, meanwhile, had gimped his arches from walking barefoot in the sand all day with heavy weight. He hobbled around like a wounded animal. We followed the tracks of the wild dogs, Javan rhinos, boars, and wild buffalo that had blazed a trail along the beach before us.

At the end of Cibandowah Beach, we looked for some sort of trailhead to take us through the jungle. A small brown patch stood out in the grasses on top of a rock shelf where the beach ended and the forest began. Tired of trudging in sand, we welcomed the change of scenery, and headed down the narrow, sloppy jungle path.

At the end of Cibandowah Beach, we looked for some sort of trailhead to take us through the jungle. A small brown patch stood out in the grasses on top of a rock shelf where the beach ended and the forest began. Tired of trudging in sand, we welcomed the change of scenery, and headed down the narrow, sloppy jungle path.

It led through ankle-deep mud and over and under fallen logs. Leaf monkeys and gibbons squawked and jumped in the canopy above as I passed in the approaching dusk. Biting flies and mosquitoes hammered me as I moved slowly along the trail.

I lathered on 95-percent Deet Muskol on my bare arms, legs, neck and face to keep the bugs at bay. Unfortunately, I was sweating so much, the bug-dope didn’t last long, and they came back again. I put on more Muskol again and again, but it was only effective for a brief time with each application, and I was bitten all over in between.

Near dusk, about three kilometres along the path, I came upon a bare patch of grass on top of a lava cliff overlooking the bay, and decided to make camp there. I dropped my bags and doubled back for my final load, telling Dave about the site as I passed by. On my way back with my last pack, I cheered Dave on as he made tracks for his last load.

Arriving at the camping spot thoroughly sweaty and grimy, I clambered down the cliff to a small beach, where I took a dip in the ocean. My shoulders had large, open wounds from the packs, and they stung as I submerged beneath the surface of the ocean.

I was spent. My head ached and my stomach felt queasy. I had pushed hard for 12 hours, and felt terrible. I had picked up some sort of bug, and had diarrhea. I walked slowly back to the campsite. Dave was sitting, gazing out at the ocean with a stunned stare. When I approached, he jumped and said “Whoa-It’s you . . . have I ever got a story for you!”

I sat on the rock beside him and he began telling me about his last half-hour. He had been walking down the trail focused on the ground, putting one foot in front of the other, when he heard a loud rustling in the bushes. Before he could react, a good-sized leopard sprang onto the trail only two metres in front of him.

His eyes and the wide, focused eyes of the predator met for a moment, then it leaped from his path and disappeared. He had gathered himself together, trying to still his pounding heart. Dave then moved on, figuring that the leopard had been more scared of him than he of it. Dusk was turning to dark, and everything went eerily quiet.

Dave flicked on his headlamp and continued on, following the beam of his light through the inky blackness. With his injured foot and large pack, he hobbled along like Quasimodo. After 15 minutes, Dave approached a dip in the trail and was about to step over a log when he heard a sound that sent shivers up his spine and made his hair stand on end. A deep, guttural growl rose from just off the trail, and Dave froze. The leopard was stalking him.

With his hobbling gait, he probably looked like a potential meal; predators always target the sick and the weak. Trying to control his panic, he walked the rest of the trail expecting the big cat to pounce on him at any moment. He arrived at camp relieved and a little shaken.

Dave’s been through a lot of experiences in his life as a guide and adventurer; it takes quite a jolt to get him unnerved. I listened to his story with astonishment but, with my intestines in knots, I felt too miserable to react. Adding a leopard to the mix was a bit too much for me to process, so I just discarded it.

I’d had lots of bear encounters in my past, and I didn’t worry about large mammals too much. I was more worried about severe dehydration, since I couldn’t keep food and water in me for more than a few minutes. Exhausted, we decided to turn in for the night.

The mosquitoes were already starting to come out. We pulled the tent out of the pack, but the tent poles weren’t with it. Exhausted and frustrated, we searched through everything until I realized that I had left the tent poles 18 kilometres back, at our beach site on the dune. With the mosquitoes out in full force in a renowned malaria zone, we couldn’t risk sleeping out. (The mosquito that carries malaria comes out to feed at night.) We improvised, and strung the fly up from some trees, then suspended the tent body from the fly.

We would need sticks to use as makeshift tent pegs. I walked off, searching the jungle’s edge with my headlamp for some sticks, when something caught my eye. Hundreds of fireflies were moving about like a pulsing galaxy in the blackness of the underbrush. Two of these flies were very large and still, lighting up only when I shone my headlamp at them.

As I continued to look at them, I slowly realized they weren’t fireflies at all, but the eyes of the leopard. I could make out the outline of his large head as he crouched perfectly still, gazing intently at me, only four metres away. In my tired, sickly state, it was more than I could deal with. I just shrugged, went back to the site, and told Dave, “Your leopard friend is back.” He mumbled something like “Great…just great,” and we both went to bed. What else was there to do? I spent the night popping Imodiums like candy, and jumping up to relieve my bowels outside the tent.

The Imodium hadn’t worked and, by morning, I was very dehydrated. One positive result of my diarrhea was that I had unintentionally made a circle of scent around our campsite that seemed to ward off any potentially threatening wildlife, including the leopard. We had treated all of our water and Dave was fine, so we figured I must have gotten sick testing for brackish water, even though I had always spit it out.

I went to my emergency kit for a dose of antibiotics, and within half an hour I could take in water and food again. Our day began with a six-kilometre jungle slog to the main beach in Karong Ranjong Bay. This time, I suited up in long pants, long-sleeved shirt, socks and running shoes, along with lots of bug dope. We were both quite weak from the day before.

Dave’s feet were killing him-he had serious tendonitis in one arch-and I was still dehydrated. The trail was similar to the previous day’s trail, and we made the beach in relatively good time. After trudging another two kilometres on the beach, we arrived at a grassy opening with a scattering of open-air shelters and a larger thatched-roof bungalow at the back. Dave and I turned to each other with blank, disbelieving faces, looked back at the opening, dropped our packs and walked side by side into the camp. As we neared the bungalow, a weather-worn sign spelled out in dull yellow letters, “Karong Ranjong Ranger Station.”

Dave and I turned to each other with blank, disbelieving faces, looked back at the opening, dropped our packs and walked side by side into the camp. As we neared the bungalow, a weather-worn sign spelled out in dull yellow letters, “Karong Ranjong Ranger Station.”

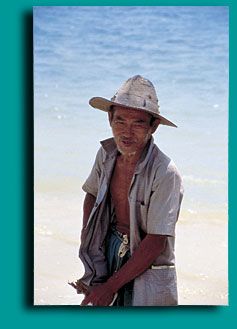

Three men stepped out of the darkness of the front door and walked to meet us. All had black, tousled hair, dark skin and gleaming smiles. The slim, moustached man in the centre wore a beige ranger’s shirt, shorts, and flip-flops on his feet; the other two simply wore ragged T-shirts and shorts with bare feet. Machetes hung from belts at their sides.

In broken English, the point man with the facial hair introduced himself as Arnasan, and his two friends as Hutbi and Tegbuh. They were the park rangers for this sector of Ujung Kulon.

Arnasan immediately invited us in and offered us tea and a much-needed lunch of ikan goreng (fried fish), rice and greens. (A few days of pure Spam and oatmeal builds up your taste for other food-any other food.) Arnasan spoke a bit of English, and gave us excellent information on which trails would best get us to Tamanjaya.

The rangers get here on foot as well; Arnasan said boats just don’t land along this stretch of ocean. They take a day to hike in from Tamanjaya and spend a month at a stretch here, doing one seven-day walk-about during that time. For dinner, we had Spam fried over the rangers’ fire, along with some rice and noodles they offered us. Even though I wanted to rest, I hiked the kayak pack partway down our next day’s trail, to give us a head start for the morning.  Using our phrasebook, we chatted with the rangers into the night.

Using our phrasebook, we chatted with the rangers into the night.

All of the rangers had contracted malaria at least once. Armed with machetes and rifles, their main job is to protect the wildlife here-especially the Javan Rhino-from poachers. There are only 60 left in the world, all of them in Ujung Kulon. I was so dehydrated that I drank 15 glasses of water and five cups of tea, and still couldn’t pee but, thankfully, my diarrhea was gone. We went to bed feeling a lot better than the day before. The next morning, the rangers offered to help us with our load but, after carrying a couple of our packs for about 20 metres, they decided we’d best do it ourselves.

They were a diminutive trio-the rangers, like most Indonesian men, stood between 5′ and 5′ 5″. Carrying packs close to their own body weight didn’t sit well with them. Offering them a hearty terima kasih (thank you), we set to our task. Our day’s trail would take us four kilometres, to Selamat Datang Bay. The route ran through a swamp, so I prepared the battle gear. I wrapped my head in a smelly, Muskol- and dirt-soaked T-shirt, with only my face peering out of the shirt sleeve (an old tree-planting trick).

The only parts of my body that were exposed were my hands and face, which were liberally covered with Muskol. We sloshed in a monsoon rain downpour through ankle- and knee-deep mud and water, accompanied by a cloud of mosquitoes and biting flies. The duffel-bag straps ripped my shoulder scabs open for a second straight day.

My skin dissolved from the bug dope. Birds were chattering, monkeys screeching; lush ferns and palms glistened with the new rain and humid jungle heat. The jungle opened up a little, and we began to see open sky through the cracks in the foliage ahead of us.

We pushed on through, and arrived at the southern tip of Selamat Datang Bay. Mangrove trees, fallen logs and bushes crowded the shoreline with open water beyond. There was no sign of civilization save for a fishing boat moored 50 metres off shore. We stumbled over the raised roots of the mangroves into waist-deep water, and flagged it down. Its old diesel engine fired up and the boat smoked and sputtered its way to within ten metres of us. The boat’s sole occupant was a young man who appeared to be more than a little curious as to what we were up to. Having a better grasp of Bahasa Indonesia (the native tongue) than Dave, I negotiated a price of 50,000 rupiah (US $7) for him to take us to Tamanjaya, a half-hour boat ride away.

We pushed on through, and arrived at the southern tip of Selamat Datang Bay. Mangrove trees, fallen logs and bushes crowded the shoreline with open water beyond. There was no sign of civilization save for a fishing boat moored 50 metres off shore. We stumbled over the raised roots of the mangroves into waist-deep water, and flagged it down. Its old diesel engine fired up and the boat smoked and sputtered its way to within ten metres of us. The boat’s sole occupant was a young man who appeared to be more than a little curious as to what we were up to. Having a better grasp of Bahasa Indonesia (the native tongue) than Dave, I negotiated a price of 50,000 rupiah (US $7) for him to take us to Tamanjaya, a half-hour boat ride away.

We waded our load of gear out to his boat, heaved it up, pulled ourselves onto the deck, and were off. Ujung Kulon was not such a bad place to be. We had explored it by kayak and by foot over six days, and saw a total of five people, all of them locals or rangers. If our kayak hadn’t broken up on its shores, we never would have had the full range of experience that, in retrospect, I will cherish.

onto the deck, and were off. Ujung Kulon was not such a bad place to be. We had explored it by kayak and by foot over six days, and saw a total of five people, all of them locals or rangers. If our kayak hadn’t broken up on its shores, we never would have had the full range of experience that, in retrospect, I will cherish.

Sometimes suffering is the only way to achieve such experience. If I get malaria because of it, I’m sure the suffering will continue. Afterword: With only three weeks left and no way to repair the kayak, we headed to Bali via bus. There, we rented a couple of bikes for a buck a day, and did a weeklong lap of the island. After that, we hiked up a couple of volcanoes and learned to surf.