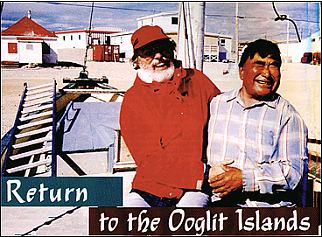

Igloolik-A grand re-union with some old hunting pals. Here Enuki Kunnuk and I share a laugh about who was better fed over the years and who got older looking…In the background is the town of Igloolik. The small white building with the red roof is one of the last of the former Hudson’s Bay Company buildings remaining from the old days of the north.

Igloolik-A grand re-union with some old hunting pals. Here Enuki Kunnuk and I share a laugh about who was better fed over the years and who got older looking…In the background is the town of Igloolik. The small white building with the red roof is one of the last of the former Hudson’s Bay Company buildings remaining from the old days of the north.

Ooglit-the place where the walrus haul out to sun themselves. An Inuit word for an ancient place. A mysterious place of tent rings, houses and circles made of giant stones, fashioned by a people long gone. A place changed by people, climate, sea creatures and time itself. A place to visit, especially as the old ones must have: by paddling an umiak or a kayak.

In the last week of July, I stood a dozen feet or so above a glassy sea in 18°C weather, on the top of several terraced beaches. Looking north, just barely visible from this slight rise above the water, the Ooglit Islands appeared to come and go, a mirage hanging above the sea. My kayak lay at the water’s edge, my lunch camp ready to be packed away. I hesitated. I knew that the arctic weather could change from placid to furious in an instant. I would definitely be taking a risk going so far offshore. I took a compass bearing. The 60°N bearing from the point here at Nugsanarsuk, out to the islands was a bearing that only a fool would trust. This close to the magnetic pole, a bearing was more changeable than the weather. It was three in the afternoon on a day when the sun wouldn’t set for another few weeks. I launched the kayak and slipped into the cockpit, tightened the spray skirt and dipped the paddle into the mirrored surface.

From the water, I couldn’t see the islands at all. Still, the Ooglit Islands drew me like a bevy of sirens, tempting me. I had visited these islands almost 30 years ago while hunting with several Inuit. We had harvested several walrus among the ice floes farther offshore and had cached the meat on the island.

It had been a brief visit, but it was vividly etched in my memory. This was finally my chance to return. I would paddle from Hall Beach to Igloolik and, along the way, stop at the Ooglit Islands.

It had been a brief visit, but it was vividly etched in my memory. This was finally my chance to return. I would paddle from Hall Beach to Igloolik and, along the way, stop at the Ooglit Islands.

My kayak was flown from Montreal to Iqaluit on Baffin Island and then to Hall Beach on the Melville Peninsula. I followed it a few days later. I got a ride into town from a lanky, friendly guy in a pickup truck and asked him to take me to the village “campground.” We laughed. There was no campground, of course. I could have camped anywhere. He took me to a beach made of small, flat, grey stones, many bearing fossil impressions, at the north end of the village. Nearby were the tents of several Inuit elders who had abandoned their wooden houses for the summer months. Early the next morning I loaded the kayak. After several false starts, I managed to fit everything in except my sleeping bag, which I stowed in a dry bag on the deck behind the cockpit. I had brought along two closed-cell-foam pool-noodles to use as beach rollers. They worked perfectly, allowing me to ease the laden kayak down the sloping, pebbly beach. The water was dead calm, reflecting the partly cloudy sky like a mirror. I began following the barren shoreline northward.

Terraced beaches rose, one above the other, relics left over from the last ice age as the land, relieved of its icy burden, rebounded out of the sea. Fifty feet above the water, the rows of gravel level off and stretch inland in an almost unending series of tundra ponds, sedge meadows and low ridges without a bush or tree in sight.

I paddled a half mile off the beach, where the water was free of ice and rock hazards. The bottom was clearly visible and rocky, with a sparse covering of kelp streaming in the tidal current. Paddling for miles along such a monotonous and low-lying shore, I was never precisely certain where I was. After three hours of paddling, however, when the land turned westward into a deep inlet, I knew I had arrived at Nugsanarsuk. A beacon tower allowed me to establish my position exactly. I rolled the kayak up the beach on my foam noodles and made lunch. From the top of the highest beach terrace, looking north, I could see the Ooglit Islands for the first time. Since they could not be seen from the water, the bearing back to the beacon would become my only reference point.

As I paddled out, the horizon seemed to curl up and away from the boat, as if reversing the earth’s curve. Pieces of ice scattered around seemed strangely suspended from the sky, giving the impression I was paddling inside a smooth blue sphere of water that curved seamlessly into the sky above. The light was beginning to play tricks on me, so I kept my eye on the deck compass. Sixty degrees. About an hour into the crossing, for the first time since leaving shore, I spotted the islands, but they were lifted up, as though they were merely a mirage above the sea. I could see the shadows in the rocky headlands contrasting with some patches of white ice still attached to the shore. Then the mirage dissolved and the Ooglits were gone. I had to keep reminding myself: sixty degrees. I kept turning to check Nugsanarsuk Point behind me. Was I drifting off the bearing? I didn’t want to miss the islands and paddle out to sea! Another hour of paddling and the Ooglit Islands “mirage” made a gradual transition into the real thing. Still, they played a game of disappearing, only to reemerge in a different shape. My confidence began to falter. Patches of fog rose up and drifted past the islands, hiding them once more from view and adding to my confusion. Sixty degrees. Another half hour and I knew the Ooglits were ahead of me. As I neared the shore, currents twirled chunks of ice, big as boxcars, past me. At last, I beached the kayak on a falling tide on a sandy shore between two rocky headlands of dark pink granite.

Screaming terns and Sabine’s gulls swirled overhead as I set up my tent at the top of the beach. My thirty-year absence was over. I couldn’t wait to begin exploring. I climbed one of the granite headlands to get a look at the layout of the Ooglit Islands. I was on the largest island, North Ooglit Island, the only one with any obvious signs of past human occupation. The others were just gravel strips a few feet in elevation above the sea, visited only by birds. From the headland, the half-mile-wide band of bare, treeless land stretched two miles northward. Bays and tidal inlets cut deeply into the sides of the island, some completely emptied of water at low tide, with reversing tidal streams where the seawater flowed in and out twice a day. There were more gravel beaches, sedge meadows and shallow tundra pools. Granite bedrock jutted out in clumps here and there. About halfway down the length of the island, silhouetted against the evening sky, I could see five house ruins and some other strange structures.

Supper would be late. I clambered up the coarse, sandy beach and out of the little bay, the arctic terns and Sabine’s gulls squawking again in full fury. Walking north, I skirted rocky outcrops and shallow pools of clear water, teeming with aquatic insect life. The ground was pocked with hundreds of 2-inch holes in the ground-tunnels made by lemmings leading to their burrows-and round, shallow indentations, the empty nests of summering birds. Farther along, where an inlet cut halfway into the island, I found scores of stone tent rings, placed as if waiting for their owners to reappear and set up camp. The stones were the size of five-gallon gas cans-big enough to hold up a skin tent in the strong arctic winds. Behind the dozens of tent rings rose a gravel ridge with the remains of five Thule-culture houses. Each house was built of a circle of large boulders packed with moss and turf. Inside, flat stones were used for flooring, walls and the built-up sleeping platforms opposite the entrance. More stone was used to line the underground passageway leading outside. The roof was now open to the sky, but the presence of large whale rib bones suggested that they had once been the supports for a seal- or caribou-skin roof covering.

From the house ridge, I spotted a large circle of stones on a hilltop near the eastern shore. It was 20 feet in diameter, made of giant stones piled up chest high. Three taller stones, well beyond the height of their neighbours, were precisely positioned equidistant from each other around the circumference. In the center was a block of granite about four feet high and two feet along each side, with the sides squared off and a flat top. An altar stone? The site had been built on the highest point of land, commanding a view over the Ooglit Islands, the surrounding seas and, far off to the west, the distant hazy line of the mainland. Now at midnight, the dull, reddish sun was low in the northern sky, about to momentarily touch the horizon before rising again for a new day. Deepening shadows had spread across the island and I still hadn’t had supper.

The next morning, I sensed a change in the weather. While it was still sunny with only a few clouds, a light breeze had come up from the west. I would have to leave quickly or be stranded, possibly for days. By eight o’clock I had packed the kayak and was on the water. I paddled around the western shore looking into each inlet for possible signs of walrus and checking each rocky islet for seals before I reluctantly headed northward toward Pinger Point on the mainland. I passed three of the other Ooglit Islands, barely showing above the water and covered with hundreds of sea birds. The tidal currents were stronger now, and highly variable winds were just off my port bow. I passed through a number of tidal rips and through several lines of ice pans trapped in eddies. Guillemots and arctic loons skimmed ahead of me and then circled back for a closer look.

Again the sea air played its tricks: Pinger Point loomed high and solid in front of me, only to collapse into the water, leaving no sign of itself. Tall headlands rose up to the west, yet there was no land for nearly five miles in that direction. The constantly changing view confused and baffled me. Several times I was tempted to change course for what seemed to be the closer headland, only to have it disappear. Worries began to flood my consciousness. What if I headed out into Foxe Basin where nothing blocked my passage for dozens of miles? Even the compass was no longer as steady as it had been the day before. The only choice available to me was to continue paddling, trusting the sun’s position and the wave direction, which seemed to be the only constants.

By eleven o’clock, Pinger Point finally remained fixed and solid-looking and, a half-hour later, I was paddling alongside its gravel base. Dozens of ice pans were trapped in the shallow water, forming a maze of channels through which I wound. Many of the ice floes were crazily tilted with massive overhanging sections that dripped icy water down my neck. By noon, I had made it around the point and was relieved to find myself once again in clear water and heading northward. It was time for some lunch. As I readied my meal, the winds began to rise, first to 15 mph, and then higher. I was grateful to be off the island and back on the mainland. By two o’clock, the winds died away and I launched into a choppy sea, again moving along the shore. I could see from the kelp fronds that the current was working against me. I wanted to camp that night by one of the streams marked on the chart, but I couldn’t find any of them. I finally realised that water ran in them only during the spring. I had been passing their dry beds one after the other. I turned the kayak toward the next one I saw and rolled it safely up the beach above the tide line.

Early in the morning I awoke to the roaring sound of a windstorm, with my tent roof pressing down on me. The wind was blowing so strongly the tent was nearly flattened. Outside, the sea was a boiling mess, covered with wind-driven ice pans, spindrift and whitecaps. It was not going to be a paddling day, that was certain. To keep the fly on the tent, I wrapped duct tape around the anchoring sleeves at either end of the ridge pole and tied the biggest rocks I could carry to the guy lines. Then I buried the windward edge of the tent floor in the beach gravel, in hopes it would stop the wind from lifting the tent and carrying it away. Once I was satisfied it was not going to blow away, I went for a blustery walk. I found more Thule houses strung along the shores of a large tundra pond. The yapping of a grey fox alerted me that one of the abandoned houses was inhabited. He had dug tunnels throughout the ruined structure, and the land around the house was a brilliant green, contrasting with the monochrome beige of the surrounding landscape. It was the only place for miles getting fertilised on a regular basis.

Offshore, in the dark blue sea, hundreds of ice pans rushed dramatically past and then disappeared over the horizon. Dark clouds on the northwest horizon scudded toward me, spreading their shadows across the land. With the clouds came calmer winds and my chance to paddle again. I pushed the boat into the surf at 6:30 p.m. and charged through the breaking waves. After I had paddled a mile or so, the land turned southwest, forming a large, shallow bay. Hoping the wind would remain relatively calm for a while, I spotted a grounded ice pan on the bay’s northwestern shore to use as my reference point, and started across. The wind was very unsettled, first blowing strongly and then dying entirely, but by eight o’clock I reached the shore and was heading northward toward Igloolik once again, now only a day’s easy paddle away. The wind began to blow steadily soon after I made it to the coast, so I began looking for a campsite.

There was no beach in sight, and the steep gravel banks along the shore would make landing difficult-and hauling the kayak up above the tide line seemed impossible. Several times, I stopped to check out likely sites, but having to unload the kayak just to get it up the beach wasn’t appealing. The chart suggested that the coast would begin to flatten out a few miles along, so I dug in and paddled into the waves. By eight thirty a low point lay ahead that looked promising. I was wet and tired from constantly heading against the wind with waves breaking over the bow. I would have to stop on the point, no matter what it offered for a campsite.

As I rounded it, I saw a small wooden cabin, four white tents and a group of people who had turned to watch my progress. I angled in toward shore. What luck-I had paddled into an Inuit summer fishing camp. I nudged my way in, trying to avoid the submerged rocks hidden in the waves. Two big teen-aged boys wearing hip-waders walked out and guided the boat in. As I got out, I fell down on the hard, stony beach, a victim of cramped leg muscles and wet, slippery seaweed.

A cheery-faced man of about forty sporting a Fu Manchu moustache grabbed my cold, sore hand in his very warm one and helped me up. Two families were using this fishing camp: Lucien and his teenaged son Paulo, and Maurice and his wife Annie with their four children. Within seconds, we were all in Maurice’s tent where Annie offered me biscuits, hot tea and one of their tents in which to stay the night. Their kids, ranging from 4 to 14 years old, gathered around, anxious to get a look at their surprise visitor. Both my hosts and I tried to remember if we had ever met before, but we decided they had been too young to remember my previous visit.

Moving my belongings into the tent, I immediately recognised the layout. The floor plan was identical to the ancient ruined houses on the Ooglit Islands. Caribou skins were laid out on the slightly raised sleeping platform at the rear, and fishing gear was piled on either side of the doorway.

During the night, the winds again began to increase and, once more, I woke up with the tent flapping and pushing down on my sleeping bag. Getting up, I went outside to check what was happening. I wasn’t alone! Everyone was up, pulling on the stones to which the tent ropes were attached, moving them back to where they had been. The wind had dragged mine several feet. I added several more stones on top of each anchor stone, but even this was not sufficient, as the powerful wind continued to drag the stones. Finally, I attached my ropes directly to the next tent upwind. Satisfied that I wasn’t going to blow away, I got back into my sleeping bag. Within minutes, the whole tent came down on top of me. The ropes had pulled away from the tent completely. I crawled out from under the collapsed tent and placed some of my extra rocks on the tent to prevent it from tearing or blowing away entirely. I headed for Maurice’s tent. Alex, his 14-year-old son, was up making tea. We filled our mugs and began eating bannock when, suddenly, the tent came crashing down, waking the whole family. Alex wisely extinguished the kerosene heater before it caused any trouble, and the younger kids pulled on their clothes and went running after the family’s belongings as they disappeared downwind. The two other tents were also down, leaving only the wooden cabin still standing.

While Annie and the children collected things, the men and I rushed to save their canoes before the waves pounded them to pieces on the beach. We pulled Maurice’s heavy, 24-foot freighter canoe up higher on the beach. We walked the other canoe to a small stream nearby, where we pulled it upstream out of the surf.

We all moved into the little cabin, nine of us in the ten-by-twelve-foot building. As there were no windows, Maurice rigged up a lightbulb to his portable generator and we all took turns keeping the generator filled with gas while it ran all day without stopping. By the next day, Annie had had enough of the dark cabin interior, not to mention the noise and smell of running the generator all day long. She got Maurice to install the window he had brought from the dump in Igloolik. He wanted to put it into the roof, for fear that polar bears would break it during the winter, but in the end we cut a hole in the north wall and put it there. Next, we repaired the roof with tar paper to prevent the occasional rain squalls from spilling in through the cracks between the plywood. Fortunately, the paper was very heavy, so it was possible to roll a bit out and tack it down in the wind, which was gusting to 45 miles per hour.

Several times during our repair project, when the cabin door was unlatched, the wind would catch it and fling it open wide. If you happened to be hanging onto it, you would be catapulted out to the beach. After everyone had been flung out enough times, Maurice and Lucien built a lean-to wind screen to protect the entrance from the wind.

On the second day of the wind storm, Annie kicked us all out of the cabin and spent the day over a sizzling frying pan, cooking mounds of fresh bannock. While the kids went for walks on the beach, Lucien fished for char, which he caught nonstop in his nets, and we all ate like royalty that night. Throughout the three days of the storm, we were in touch with Igloolik and other camps in the area thanks to the CB radios everyone used.

On the third day of the wind storm, in the afternoon, the weather began to show signs of a break. The wind began to die down and the whitecaps became less frequent. We decided to head into Igloolik. By nine o’clock in the evening, both canoes were loaded to the gunwales with people and supplies and, with engines roaring, they began making their way across Hooper Inlet to Igloolik, about eight miles away. I watched as they made their way across, amazed at their warm hospitality shown to me, a person they had never met before.

Rather than head straight across the inlet, I decided to follow the shoreline and cross to Igloolik Island at the narrowest point, shortening the open crossing to around seven miles. I rolled the kayak down the beach and plunged into the surf. The waves were still about two feet high and coming from several directions at once. The wind was around five to ten miles per hour. It was going to be a wet ride.

Half an hour later, I reached the narrowest section of the inlet and headed across. The waves and currents made for a very jumbled sea. I soon realised that I would have to paddle hard constantly-there would be no letup all the way across if I were to get there. I was splashed by waves as they rushed by, with the wave crests washing over my deck.

In spite of my hard paddling, the shore ahead never seemed to get any closer. After about an hour, however, I began to see people driving around on their ATVs. I adjusted my landfall slightly to enter Turton Bay, which held the town of Igloolik. The hills behind the town provided a welcome windbreak. Even so, it took another half-hour to make my way to town. The gathering darkness of midnight, deepened by thickening clouds overhead, made it difficult to see where to land. Soaked and exhausted, I finally headed toward a group of people gathered on the beach. As the bow touched the shore, I could see Leah, a friend from Igloolik I had met here thirty years before, her brother John, and her uncle Qaminaq, the man who had first taken me to the Ooglit Islands. They were all there, waiting to greet me. I got out of the kayak and, this time, managed to stay on my feet as we hugged each other, laughing and talking all at once. Maurice and Annie had called when they arrived to tell them I was on my way, and to watch out for me. Leah had been one of the people on the ATVs I had seen, watching to make sure I was all right in the rough-water crossing.

We walked up to Qaminaq’s two-story house to meet Joanna, his wife, and one of their daughters, now married with children of her own. His son, Naisana, was no longer a toddler dressed in caribou furs, but now a father of toddlers. We downed mugs of hot, sugary tea and mouthfuls of fresh bannock. We all grinned at one another, laughing, smiling and trying to talk all at once, not really knowing where to begin the conversation. Leah worked hard to translate, but the words, mingled in two languages, came in a flood. There was just so much to say after nearly thirty years of being away. It was good to be back and especially to have returned in the traditional way, in a kayak, and from the Ooglit Islands, the mysterious islands of the past.