While kayaking round mainland UK in 1996 with a partially sighted lad, we encountered some very rough waters. One day in big seas, the bow of our 24-foot double was not touching the bottom of the trough and the stern was not touching the crest of the wave. I jokingly said that it would probably be easier to paddle the Atlantic Ocean than to endure the conditions we experienced. It was not until about six months later that I seriously considered researching the feasibility of a solo, unsupported crossing of the North Atlantic Ocean.

The following February I went to our annual canoe and kayak show where all the retailers and builders would be, and I started to plan the challenge. The show was the ideal opportunity to gain valuable contacts and seek sponsorship. However, only two companies were willing to help:one to supply the paddles and one who was interested in building the kayak, for a fee. I wanted a boat that could carry 100 days’ worth of supplies, be self-righting, that I could sleep in, and yet it should still look like a kayak.

In just two days, Jason Rice (a member of the company who built the kayak) came up with a working model. A civilian branch of the Navy, called Haslar, checked the design by using a model in simulated conditions in a special water tank to test the sea-worthiness of a ship. After successfully completing the tests, construction began. A friend put me onto a retired businessman named Jim Rowlinson. We had a meeting to discuss what I had accomplished to date. Jim was influenced by my determination and believed the project would be a success. He became the project manager, on the condition that he received no payment, and set about raising the money needed. In 1999 we travelled together to St. Johns in Newfoundland, the starting point of the journey. Through a number of contacts we were lucky to meet Linda Bartlett, who worked for the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Tourism, Culture and Recreation department. Linda was impressed by our enthusiasm and had every faith in what we were trying to achieve. She helped us immensely to fulfil our needs in Newfoundland: gear storage, accommodations, transport. Linda also introduced us to key personnel needed to help us once we arrived with the kayak. As luck would have it, there was a sea kayak symposium in Corner Brook to which I was invited to give a presentation on my planned challenge.

I decided to set off during the month of June the following year, to arrive in Irish waters before our winter started. As no onefrom the canoe and kayak show stepped forward to help with clothing, I was introduced to an outdoor clothing company, based in Scotland, that tends to specialise in mountaineering gear. They kindly offered to supply me with the apparel I needed for the challenge. Jim began to collect all of the equipment that I would require, from spraydecks to emergency kits, including a very comprehensive first aid kit. We had a special trailer built to take the kayak around the UK for trials, and ‘LandRover’ sponsored a 4×4 vehicle to tow the trailer. In order to raise financing, on these tours we gave presentations to help promote the challenge. In the eleventh hour, an Internet auction company became our main sponsor. With a secure sponsor on board, we were able to head off to Newfoundland and wait for good weather to commence the challenge.

After a couple of weeks making final preparations in Newfoundland, I got the weather that I needed: a window of five days of Westerlies. I started at about 20:00 hours as the tide was turning to help me paddle out of St. Johns. The media and a few hundred well-wishers were there to see me off. Four sea kayakers escorted me out through the narrows before turning into the small harbour of Quidi Vidi. Jim followed me out in a fishing boat with a film crew and then turned back for St. Johns harbour, leaving me to paddle through the night. There were a few long liners heading for St. Johns but nothing else. It was a clear night and after three years of planning I was finally on my way and enjoying it. I felt good.

My speed while paddling was 3 knots, as registered by the GPS. I was very pleased with that. In the morning, out of sight from the land, I was well and truly on my own. I had covered about 40 miles-a good night’s paddle-and it was time to get some sleep. Once I had changed my clothes and was in my sleeping bag, it did not take long to fall sleep, but I managed only a couple of hours. Waking up, I looked out the small porthole to see rain pouring down, and decided to go back to sleep. About 12 noon, I woke again and decided to call Jim and let him know everything was going well. I moved some bags and noticed water in the cabin and wondered where it had come from! I opened the air vent in the door and put my hand through to feel for any water in the cockpit. There was water over three-quarters of the way up the door. This was a serious problem. A bilge pump system was installed through all the compartments to the cabin, for just such a scenario. Using this, I started to pump the water out of the cockpit via the cabin. Realising I was making no progress, I had to get into the cockpit and use the hand pump. I decided to take my watch off, because I would be immersed in the water and although it was water-resistant, it was not waterproof.

While I was in the cockpit pumping the water out, the sea became rough enough to tip me overboard. A re-entry procedure involved my having to pull myself up by reaching over the side of the cockpit and hauling myself in. This happened twice. The sea was now coming in faster than I could pump it out. I had to make a decision that I was not happy with, but there was nothing else I could do. I got into my life raft, after activating the canister to inflate it. Because of the rough sea conditions, the life raft was thrown against the kayak, ripping a hole in the bottom. I spent the next 32 hours in sea temperatures of 3 degrees C above zero, pumping water out of the raft every few minutes. I survived the ordeal by planning next year’s trip. A Newfoundland Coast Guard ship, the Cowley, eventually picked me up.

Before I left the kayak, I attached a 30-inch sea anchor/drogue made of nylon onto her, yet when she was picked up later by the Cowley, she had a 12-inch silk drogue on. This led us to believe that the kayak was found by a vessel that claimed salvage and stripped her of all our equipment. There was no other explanation for the loss of my kit.

It took over four months for me to regain feeling in my feet and to learn to walk again. At the same time I had to find another builder and get all the equipment together. Kirton Kayak of Crediton in Devon built the new boat with the help of a yacht designer. She was made with the state-of-the-art materials that made her lighter but tougher. We used the same hull mould but changed everything inside (including the layout of the cabin). There was an electric pump alongside foot and hand pumps. A yacht hatch was used for the door.

Most of the equipment sponsors stayed on board and some even insisted, “You must try again,” before I told them that I was planning to. The foot-and-mouth epidemic put me out of work as an outdoor pursuits instructor; therefore, I had more time to help with the construction and did some of it myself.We were able to use Nigel Dennis’ kayaking centre in North Wales as a base, to enable us to carry out sea trials with help from the RNLI (Royal National Lifeboat Institute).

Our main sponsor had pulled out and even though we had a company filming footage of the challenge, from the building of the kayak to the trials, we could not get another main sponsor. We managed to get on TV, into the papers, and on the radio, but still nobody was interested. I had to make a decision; wait until we got a main sponsor (some of the equipment sponsors could not wait), or go forward with the expedition and hope for the best. Without a financial sponsor I had to borrow the money, knowing the only way to pay it back (if still no sponsor came on board) was to sell my house. I am a doer and not a talker, so I decided the first week in June to send the crated kayak to Newfoundland, regardless of the financial situation.

Jim and I followed a week later, hanging on as long as possible in an attempt to secure some kind of sponsorship deal, but to no avail. A few days after arriving in Newfoundland, CBC contacted us for an interview. To our disappointment, the interview that was broadcast reflected the rescue of last year, not on the forthcoming challenge. They wanted to make an issue about who would pay for the recovery if there was another failure.

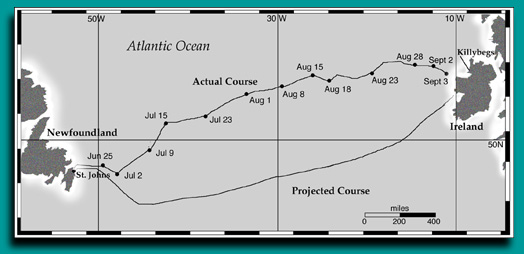

The Canadian Coastguard was once again very helpful and gave us up-to-date weatherforecasts. Jim and I would visit them twice a day when the reports came in. On the morning of June 22, the forecast was good: gentle westerly winds with calm seas. I decided to leave at 20:00 on the ebb tide. On leaving St. Johns the weather was ideal-flat seas and no wind. My sequence of targets for the challenge was to survive the first 24 hours (because of the events of last year), cross the Newfoundland waters, reach the quarter mark, reach the halfway mark, enter English waters and land in southern Ireland.

Two days out, the sea state started to worsen. The rough seas prevented me from cooking, and for the rest of the journey I ate all my meals cold. The Coast Guard informed Jim that I was experiencing October weather in June; it was the worst weather they had on record. In one night, Mother Nature forced me backwards-60 miles to the north. A couple of weeks into the journey, I encountered several problems, starting with a snapped rudder cable, which caused difficulty steering. Because of the size of the boat, a rudder was necessary to control the boat. To repair the cable, I tied paracord from the cable to the steering plate.

A couple of days later, the steering plate broke. The only way to repair this was to cut a strap from my lifejacket to make a stirrup-like fitting, as I had no means of riveting the plate back together. Shortly after completing the repair, as I was just about to start paddling, I heard a knocking sound. On investigating, I discovered the shackle from the sea anchor had disappeared. In order to repair this problem, I had to brave the elements and swim to the back of the boat. The sea state was about Force five. Not wanting to lose another shackle while undertaking the repair in such rough conditions, I decided to use another length of paracord. On getting back into the kayak I cut my hand and my blood washed off in the sea. Not long after this a shark appeared! After changing my underpants, I decided that if I kept paddling, it might think I was a machine and not an edible delight. To my amazement, this seemed to work and the shark soon swam off.

During this time I had not seen the sun once; therefore, my solar panels were not performing as well as they should have been. Everything electrical had to be switched off so that the tracking device would not fail. My desalinator demanded too much power, so I had to start rationing my water.

One hundred miles from the halfway point, after a good days’ paddle, I undressed (as I did after every paddle) in preparation for getting into the cabin. I lifted the hatch to find that the right hinge had broken. This had been the only imaginable scenario that would have the dire consequence of putting an end to the expedition!

I could not believe my luck; yet again my crossing was to fail due to a ‘technical’ problem. All I could do was to scream out and cry. My mind swam with thoughts of my hard effort of four years of planning, my expenditures, and the media having a ‘field day’ at my expense. They were waiting for any hint of failure to justify their negative attitude at the start.

I contacted Jim by satellite phone. I could not get hold of him, so I left a message on his answer machine telling him that it was all over. I called Jim back later about five minutes after I had calmed down, and suggested a possible solution: call for aid from a ship to help me replace the hatch. Jim told me he needed a couple of hours to try to sort something out. In the meantime, I was to get in the cabin and secure the hatch as best I could to prevent the sea from coming in. Calling Jim back, as he was unable to call me, he informed me there would be an engineer from the design firm on stand-by in the morning and to recall what equipment I had onboard for a possible repair. He also suggested we pray for calm seas.

In the morning, the sea was flat and deadly quiet. On contacting Jim he gave me a number to call the engineer, Mark. The first thing Mark asked was what tools I had on board, to which I replied, “A junior hacksaw, a knife and screwdrivers.” Our first problem negotiating the repair was that Mark spoke in metric terms and I was used to imperial measurements. First I had to find a tube measuring approximately one quarter of an inch in diameter by one and a half inches long, that I could cut into a hinge shape. The only thing that would fit this description was the soft metal casing on my file. Not having a vice or any engineering equipment, I had to use my knees to hold the tube as I cut away sections with my junior hacksaw. Imagine trying to saw while lying on your back in an enclosed space with your knees bent, acting like a vice, and holding the phone on your shoulder to receive instruction.

Having heard me swear rather loudly, Mark asked what the problem was and I informed him that I had cut through my knee! Mark asked me if I was ok. “It’s only blood!” I replied. A few moments later, I swore again. Mark asked, “What’s wrong now?” I told him that I had cut my other knee! Hearing me swear yet again, Mark asked, “What’s the matter now? You’ve only got two knees.” I said, “I know-this time I’ve cut my finger!”

During the call with Mark, I told him that there was a major design fault with the hatch and that it was absolutely useless, and perhaps he should inform the management what rubbish it was. (After the crossing, when I was back in England, Mark phoned to ask how things were. It was then I found out he was actually the boss, and they had developed a new hinge!)

After cutting the tube, I had to cut through a bolt which took some time. I had to cut it precisely, so that it protruded through the end of the tube. Once this was done, they had to be joined together. Without a welding kit, all I had on hand to join them was the sticky tape wrapped around my food. The hinge was protected by a plastic cover, which was held in place with some tape. This whole operation took over five hours! For the next four days I endured yet another storm and was stuck in my cabin the whole time. Thankfully, the hinge worked and, after the initial failure, it went on to survive the duration of the challenge.

The sea was undulating with 20- to 25-foot swells, visibility was down to approximately 100 yards and it was very quiet. The only noise was from the ‘splash’, ‘splash’ of my blades going into the water, and then suddenly there was a ‘splosh.’ I was puzzled as to where this other sound was coming from. After about five minutes I managed to angle the kayak in such a way that I could see behind me. Lo and behold there was a huge dorsal fin! As I looked to the left of my cockpit I saw the head of a killer whale directly below me. My initial reaction was to paddle to the right to get away and to shake it off. Believe it or not, the whale followed me. So I then paddled to the left-it stayed with me. I then paddled in a circle but it still stayed with me. After what seemed like a long time, I stopped paddling and shouted, “Get lost!” and to my amazement, it did!

The consequences of being upended by a whale would be disastrous, because it could severely damage the boat.

The Canadian Coast Guard informed me (through Jim) that I was too far north. For a very long time now, the current was keeping me going northwards as opposed to south. This was making me very anxious because I was in an Icelandic current and not the Gulf Stream, which is where I had hoped to be. If I continued to drift north, I was afraid I would miss Ireland altogether and be heading towards more treacherous waters. Luckily the winds changed to north-westerlies, which helped to steer me back on course.

Jim informed me that he was going to Ireland to find a number of uitable options for potential landing spots during the last two weeks of my ‘expected’ arrival. One of them was Killybegs.

While he was there, he warned me that the fishing fleet was outward bound and to be careful over the next few days.

Two hundred miles from Ireland, paddling in a Force five or six, I sighted my first ship after many weeks of no human contact. As I paddled towards it, I saw that it was the deep-sea fishing boat Mendoza. As I neared the vessel, I saw the captain come out of the bridge with his binoculars. Judging by his reaction, he could not believe what he saw; he dragged his first mate out to witness and confirm that he wasn’t going mad. I approached and paddled around the boat. Seeing the crew hauling in the catch, I shouted, “Good morning!” Their faces were a picture and they kept looking at each other, pointing at me in total disbelief.

From the time I repaired the broken hatch, I was unable to vent the cabin. Condensation had built up considerably. Over the following weeks the electronics become troublesome due to the moisture. Four days away from the finish, the main phone ceased to function. The only option open to me was to use the emergency mobile phone, which, due to the limited power source, provided just two days of communication with the outside world. If this wasn’t bad enough, the tracking device also started to act up. While in contact with Jim, he informed me ‘Stratos’ was having trouble locating me via the tracking system. Unfortunately, the communication and tracking devices were not designed to withstand such battering in a small craft like a kayak. The fact that they had worked so well for so long under such adverse conditions is a credit to the company that manufactured and fitted them. Forty-eight hours away from landing, the condensation situation worsened. Consequently the whole system shut down. In spite of all these problems, I was not fazed as I knew it was only a matter of days before I reached land.

09:12 hours on September 4, I spotted land to the south! I paddled east and the wind pushed me towards the land.

From analysing the surrounding land features, I knew I was in Donegal Bay. During that night as I mopped out the cabin with a chamois cloth, I spotted three lights on the horizon. I soon realised what they were, and quickly got undressed from my one-pieced fleece suit and lunged into the cockpit, naked-I had no time to get into my paddling gear!-as a fishing trawler missed me by a mere 100 feet! At dawn there was a thick sea mist encroaching, but around lunchtime the mist cleared to reveal the cliffs of southern Ireland. There was no way I could spend another night sleeping at sea with the cliffs so close-I was determined to paddle as far as I could and then land. About 17:00 hours I saw a small fishing boat and asked where the nearest harbour was. They directed me and I headed towards the small fishing village of Beldereg, County Mayo.

Upon entering the harbour, I spotted two gentlemen and shouted to them. At the same time a Coast Guard helicopter flew overhead. I had been forewarned that a helicopter might come looking for me. I tied the kayak up to the harbour wall and climbed up the ladder. The two gentlemen offered to help but I flatly refused, explaining that I had to walk on my own first. As I took my first step, I fell over onto my knees. The gentlemen asked, “Can we help you now?” “Yes, please do,” I replied. When I asked, “Where am I?” they looked confused. I explained that I had just paddled from St. Johns in Newfoundland and had been at sea for 76 days.

They helped me around to their cottage, approximately 300 yards away, where I was offered a cup of tea-my first hot substance in 74 days. While I was drinking the tea, the helicopter landed in a nearby field. Jim and the air crew jumped out and escorted me to the helicopter. The kayak was secured in the harbour on a trailer and covered over, and we collected it the following day. We flew to Killybegs-the place where my friends and family had been waiting for more than three days for my arrival.

The helicopter touched down on a football pitch in Killybegs where numerous friends, family, and the media gathered to meet me. After the initial greetings I was taken to the local hospital for a medical check up. The doctor was astounded by how fit and healthy I was, considering my ordeal. Most people were impressed that I was able to walk (if a bit wobbly at times), since I had been confined in a small area for a relatively long period of time and was unable to use my legs properly.

The aim of the challenge was two-fold. I wanted to raise awareness and hopefully £100,000 for two childrens’ hospice organizations, and to achieve the ‘Everest of kayaking.’ With the right boat, equipment, and mental attitude, I knew I could succeed in making a solo, unsupported crossing of the Atlantic. I felt that, due to the media’s attention on the failure of the first attempt, a golden opportunity to promote the sport of kayaking was overlooked and the challenge did not get the recognition that it truly deserved.

Afterword

I would like to thank everybody who helped ensure the success of the challenge. The childrens’ hospice charities are “Rainbow” in Leicester and “Ty Hafan” in Wales. Those who would like to donate money to these charities can send donations to the following address: 137, Brooks Lane, Whitwick, Leicestershire, LE67 5DZ. Further information can be obtained from the Web site: www.outdoorchallenge.co.uk/nakc2000

Sponsors

Mega, Lendal, Phoenix, Beauford, LandRover, Atlantic Containers, Royal National Lifeboat Institute, Keela, Kirton Kayaks, Stratos.

Welshman Peter Bray began paddling at the age of 12 and has competed in numerous endurance kayaking competitions. He served in British Army Special Forces and has been an outdoor skills instructor.