The Triangle, located on the east coast of Georgia’s Tybee Island just north of Little Tybee, is a shoal at the meeting point of Tybee Creek, the Atlantic current and strong prevailing winds. When a strong onshore breeze coincides with the spring tides, the central core of the Triangle is a washing machine of crossing, spilling and dumping waves. Outside the central core is a calmer zone lined with sandy beaches and safe landing areas. It’s a challenging kayaking playground with a wide margin of safety.

The Triangle, located on the east coast of Georgia’s Tybee Island just north of Little Tybee, is a shoal at the meeting point of Tybee Creek, the Atlantic current and strong prevailing winds. When a strong onshore breeze coincides with the spring tides, the central core of the Triangle is a washing machine of crossing, spilling and dumping waves. Outside the central core is a calmer zone lined with sandy beaches and safe landing areas. It’s a challenging kayaking playground with a wide margin of safety.

On my way back from a week in Florida paddling the Everglades with a group of fellow instructors and guides, my friend Mick and I stopped for a day on Tybee Island. The January weather had turned colder, but we were itching to get on the water to play in the Triangle. We ate a good breakfast, gathered our gear and headed out the door around 10:30 A.M.

The day was cool (high of 50˚F) with water temperature in the low 60s. The sky was overcast with low cloud cover and visibility in excess of three miles. The northeast wind was blowing between 25 and 35 knots, and high tide was to be around noon with low tide around 6:30 P.M. Mick and I decided it was the perfect day to get the biggest waves we’ve experienced to date and to see how well our skills and rescue drills would work.

As we headed to the launch site, we performed our routine risk assessment. We talked about everything that wasn’t perfect in regard to safety and how we should adjust our plans. Our list included: being only two paddlers instead of the preferred three; Mick paddling an unfamiliar borrowed boat that was a little bit small for him; cold water (I had a full dry suit, Mick had a wetsuit bottom but just a semi-dry top) and strong winds.

We reviewed mitigating factors. Mick and I had often paddled together and trusted each other implicitly. I had paddled the area on 10 previous occasions. We had reviewed the weather forecast and knew what to expect. We had flares, a VHF radio, a cell phone, water, food, spare clothing, an emergency shelter, a vacuum flask with hot water, spare paddles (one each), pumps (two hand and one foot), compasses (deck and hand) and a chart. We were in good physical and mental condition.

The wind was blowing somewhat toward land, so the worst-case scenario was that we’d end up south on Little Tybee and just have a long delay getting home. There was no apparent life-threatening danger to us. Our plan was to find many different conditions in which to test our paddling and rescue skills. I called Marsha at a nearby outfitter and filed our float plan. Marsha had become a familiar and welcome face at a weeklong symposium I had attended earlier, and I knew she’d take care of us.

Punching Out

Around 11:30 A.M., we prepared to launch into six-foot surf, the biggest we had attempted to date. After our first few attempts, we figured out that we needed to keep our kayaks precisely aligned while getting in or we would quickly be stranded sideways on the beach. We finally launched and paddled into some nice surf—some spilling, some dumping. Paddling at 10 degrees off of perpendicular to the waves proved ideal for getting through big dumping surf. It’s close enough to straight to avoid broaching yet just enough off perpendicular to allow smoother rise and fall. We managed to avoid being pitchpoled backward. Our basic skills worked well in the rough water.

On my front deck were a hand pump, a chart, a slim mesh bag holding my cell phone, a foghorn and some energy snacks. Mick’s front deck had his spare paddles. His first attempt through the breakers drove one of his spare paddles into his torso with such force that he figured he’d have a hole there if not for the PFD. Mine were fine on my back deck, and after Mick put his on his aft deck, everything stayed aboard as we got through the breakers. (Note: I now carry my spare paddle on the front deck secured in a paddle holder that prevents loss even in big breakers. On the foredeck, my spare doesn’t interfere with towing or reentries.)

Out in the rollers, we practiced our first T-rescue, and it went well. The water temperature was not too cold, and we were dressed appropriately for long immersions. The wind was definitely too strong to paddle against—we were blowing south toward the pier at a good clip. We paddled around the pier and enjoyed riding four- to six-foot following seas.

This was our first experience with such strong winds and waves big enough to hide us from each other half the time. Conversations were taking longer because we had to yell from the crests and pause when in troughs. We had enough experience together to communicate reliably with just a few shouted words. It was also reassuring that I knew Mick handled adversity calmly and realistically. I also knew we’d work well together to solve any problems.

Following Seas

At noon, as we drifted toward the Triangle, I saw some huge waves and knew from my previous experience that we should take care in our approach. We decided to head toward the inlet known as the Back River to get in some great surfing. The chart showed some submerged objects, so we angled to avoid them. I knew from some BCU surfing classes that a kayak has to be moving when big waves approach so it can accelerate ahead at the base of the waves and avoid getting lifted up by the steep wave faces.

After getting a great ride, I took it easy and tried to hold my position so Mick could catch up to me, but I reduced my forward speed too much to get ahead of the waves coming up directly astern. They were well over eight feet. The first wave lifted my stern rapidly. I slipped downward on the face of the wave, and my bow plowed a couple of feet under water. While the bow was stuck in the trough, the wave pushed the stern. As my boat angled past 45 degrees, I executed a fast intentional capsize to avoid getting pitchpoled. It worked beautifully, and putting my body into the wave kept me from getting tossed end over end and allowed the submerged bow to pop free.

All In

I let the wave pass and decided to wet exit to give Mick a chance to rescue me. Unfortunately, a big wave hit him about the same time, and he bailed out too. We got to do our first all-in rescue. We started 35 feet apart in waves that were over six feet high, but managed to swim our kayaks together. Our all-in rescue worked just as well as it did when we practiced in calmer water. We knew just what to do and did it without letting any of our gear get away from us.

By now we were in the middle of the Triangle and pleased our skills were holding up well. It was around 12:30 P.M., and for the next three hours, the wind, current and river ebb counteracted each other and held us nearly in the same position. We practiced dozens of rolls and just about every kind of rescue. We pumped out the cockpits repeatedly and even experimented with day hatch access. All of this was taking place in eight-foot breaking waves.

While doing some T-rescues, we succeeded in emptying Mick’s boat, but by the time he was back in and ready to paddle, all the water had returned. Each wave put gallons of water back in. We finally decided to just get the boat upright, put the paddler back in, and then stabilize each other and pump. Two hand pumps made the job a bit faster.

During the T-rescues in those conditions, raising the bow to empty a boat worked very well since the waves basically did all the work of lifting the cockpit above water to drain. Depressing the stern of an inverted boat to empty it failed because the boat was too hard to control, and on a slippery hull, the swimmer could easily get washed away.

I was thankful to have a paddle leash. I tried just holding our paddles during some of the reentries, and it was very difficult to do. We needed most of our effort focused on avoiding capsize (not that it didn’t happen a few times anyway), and the extra effort to keep paddles from being yanked out of our grip by the ocean was often too much. Stowing them under deck lines or bungees was only marginally successful, as they still often came free. One portion of the back of Mick’s borrowed kayak was lacking a deck line. As we were finishing one rescue, and I was stabilizing the stern of his kayak, that lack of line cost me a grip and Mick a second dunking. There’s a value of deck lines running completely around the perimeter.

Rescue Practice

I had previously practiced hand-of-god rescues on Mick until I could do it quickly. It paid off in the Triangle. When Mick capsized just as we pushed away from a completed rescue, I had a chance to use it for real. A short time later, and in some significant waves, he did a great one on me too. We tried some bow-presentation rescues, which went well too, and we executed them without overshooting or crashing into each other. To practice scoop rescues, we took turns simulating an injured paddler. The technique was challenging in waves, but it worked as designed.

In the middle of the Triangle, the churning water was making it tough to time a roll. Fortunately, we had practiced rolls often in a variety of conditions, and both of us have solid rolls on both sides. If a roll isn’t bombproof on both sides in all conditions, then it isn’t good enough.

Ballast

For best handling and quickest acceleration in big water, your kayak should be as lightly loaded as possible. Mick had placed a number of jugs of water in his day hatch, hoping to simulate an expedition load with water ballast, but it wasn’t working as he had intended, and his kayak was feeling fairly twitchy. The cargo may have been shifting slightly, which can definitely compromise stability, but in retrospect, Mick was simply too big for the boat. He has lots of upper body muscle and needed a higher volume kayak for the conditions in which we were paddling. He was tiring from handling the extra weight of the ballast, so we decided to dump the water out of the jugs.

Accessing a day hatch in big water is a chore. Because kayaks tend to orient themselves parallel to waves, we had to use our paddles to keep faced into the waves while trying to get something out of the hatch and not letting much water in. We had packed our day compartments so the items we might need could be quickly accessed. It was proving to be enough of a struggle just keeping the boats together and stabilized during this operation. The boat with the open day hatch had to be kept almost level to avoid water just pouring into the hatch. Trying to access the day hatch solo would have certainly meant capsizing.

Solo Rescues

After several T-rescues and bow rescues, we decided it was time for some solo rescues. We tried cowboy reentries but soon realized that we had no chance of getting back aboard without recapsizing, so we abandoned the idea. We also skipped attempting a paddle-float reentry because even if we could have gotten the float and paddle set up properly, it was obviously going to be nearly impossible. We would have been especially vulnerable to capsizing again when trying to stow the float and remove the paddle from the back deck. The only solo self-rescue that was feasible was the reentry and roll. We both found it worked well, although being hit repeatedly by clapotis just made it a bit more awkward and required a bit of patience and determination.

Stray Gear

We practiced retrieving kayaks and paddles that got away from the kayaker. We quickly confirmed that chasing a wind-blown paddle or boat while trying to keep visual contact with a swimmer in the water is nearly impossible. Going for the worst-case scenario, I had Mick capsize and release both paddle and kayak. Chasing the paddle wasn’t so bad, as it didn’t go far, but it was hard to see in the waves. (Note that in a life and death scenario, a paddle is expendable, especially with a spare on hand, and the priority is always to get the paddler back in the boat. In this case, Mick and I were playing and didn’t really want to lose a paddle. We were worried that if we lost sight of it, it could easily be swept away in the waves. We also weren’t terribly concerned with the speed of getting the paddler back into the boat, as we’d been in the water half the day anyway.)

By the time I got the paddle back to Mick, his boat was flying away. I raced after it, finally caught it, attached a contact tow and began the very long paddle back to Mick. He had raised his paddle high into the air so I had a chance to spot him in the waves. He was just a small dot in the water, and it was easy to see the possibility of our being separated. Mick later told me he could barely see me and began considering what it would be like to spend the rest of the day drifting alone off Little Tybee.

For my contact tow, I used a paddle carabiner to connect my deck bungees to the deck line on Mick’s boat. I couldn’t have used a towline in these conditions—even a short pigtail or webbing a couple of feet long would have resulted in the towed boat rolling frequently and jerking me all over the place. It would have added enough drag to make returning to Mick impossible.

Just as I was about to reconnect with Mick to complete this rescue drill, a big dumping wave approached me broadside. I saw it coming and put my full weight on the towed boat to use it as an outrigger to prevent capsize. No such luck. Both boats were rolled over each other and ended up inverted. My paddle was yanked from my hands as was the towed kayak I was trying to use for support. Fortunately, I was wearing a helmet, as the roll included at least one solid impact to my head.

While submerged, I thought how fortunate it was that my paddle was secured with a paddle leash, although it was tangled somehow with the kayaks and couldn’t be used for a recovery roll. I found the bungee that the contact carabiner was attached to and pulled until I retrieved the carabiner, then I found the bow of the towed kayak and used it to right myself in a somewhat self-applied bow-presentation rescue. I retrieved my paddle by its leash and resumed the long battle back to Mick.

During the paddle back, the kayaks were free to move independently but remained loosely connected. Had I attached the carabiner to a less shock-absorbing point, such as another deck line, most likely one or both boats would have been damaged and quite possibly separated. The bungee and deck lines held. (I replace mine every few years just to make sure I can always rely on them. UV degradation and fatigue can lead to deck-line failure under the strain of towing in rough water.)

Lost Gear

Finally, I made it to Mick. He’d gotten a bit cold, and I was rather tired, so the rescue was a bit more of a struggle than those we’d done earlier in the day. It was around 3:30 P.M.—the peak of the tidal flow—and we were hit by some more big dumpers while Mick was climbing back in and I was lying across his deck for support. We avoided getting rolled over each other more than once, but the force of the waves ripped Mick’s paddle out of its stout leash. We couldn’t retrieve it until Mick was back in his boat.

As we hurried to get him back aboard, I noted the dry bag that had been secured tightly inside the bailout pack on the back of my PFD was also floating out to sea. Inside it were a multipurpose tool, a signal mirror and some other survival items. As our possessions disappeared in the waves, I noticed my chart slowly releasing itself from my front deck. This was getting to be an expensive day.

With Mick back in his boat and his spare paddle in his hands, we searched for our lost items. No such luck—they were long gone. We decided we were ready for a break, so we tried to paddle back to shore. We tried staying close to each other to make any necessary rescues easier, but our fatigue was causing more frequent capsizes, and we were tired of practicing rescues. Mick also discovered that the cheap but handy spare paddle we grabbed for the day was useless in these conditions. I gave him my spare, which was as good as my primary paddle.

Towing Each Other

We took turns contact towing while the other stabilized and rested (if you can call keeping two kayaks upright in waves resting). At this point, it was clear that any form of contact tow that relies only on the towed kayaker holding the boat of the towing kayaker would be useless. Only a secure physical connection of a carabiner or a cord could keep us together and upright.

We were almost clear of the washing machine, but with the tide still running out and the wind blowing us south, drifting wasn’t an option, as that would take us to the south end of Little Tybee if not beyond. Since we had lost the chart and wanted some advice on what course to take, I used the cell phone I’d kept in a dry case to call Marsha. It was about 4:00 P.M. We discussed our options and what to expect as the ebb subsided. Her knowledge of the area provided even better insight than the chart. I made a mental note to ask for more detail next time from local sources before a launch.

We continued taking turns paddling and stabilizing. Mick was the stronger paddler, and I was pretty tired by this point; however, hanging onto his deck while he paddled was threatening to make me seasick even with my anti-seasickness wristbands. So Mick kindly let me share in the paddling and suffered some deck-holding time too. It’s a long, slow paddle, but finally around 5:00 P.M., we had one last surfing run to take us onto the Little Tybee beach well south of where the Back River meets the Atlantic.

Ashore at Last

We dragged our kayaks up the sand and pulled out the thermos and some food. Although we had the fixings for coffee, tea, hot cocoa or soup, we just drank hot water. It was amazingly refreshing and tasty. So were the dried fruit and nut snacks. We had burned quite a few calories during the day. Another call to Marsha ruled out taking a shortcut through a marsh, so we began a shoreline trudge back to the river mouth towing our kayaks behind us. We could have waited for slack tide and paddled, but wanted to make some progress instead of sitting for an hour.

When we reached the mouth of the river, the tide had slowed enough that the paddle upriver and across to a landing would be easy. I called Marsha to tell her our status, and she agreed to drive out to pick us up. I noticed I had lots of messages on my cell phone. Our friends had called during the day to see how we were doing and were concerned when they didn’t get answers. My cell phone had been on my deck, but I couldn’t hear it over the wind and waves; even if I could, there were few times I could have picked up the phone. I should have mentioned this to them at the beginning of the day.

The Welcoming Committee

We enjoyed the relatively calm paddle up and across the river. The wind was relenting a bit as it neared dusk, and the almost slack tide made the river easy to handle even with our fatigue. As we neared the landing around 6:30 P.M., we saw Marsha and some of our friends waiting for us. (When our friends couldn’t reach us on my cell phone, they wisely called the outfitter, and Marsha told them that we were OK and where we were meeting.)

Some U.S. Coast Guardsmen were there too. Someone on the beach had called them about half an hour after we started our paddle, probably when we were doing our first rescue drill. I vaguely recalled hearing someone mention something about “crazy kayakers” on my VHF but just wrote it off as another boater. Had I realized it was a Coast Guard communication about us, I would have replied and told them of our plans and that we were fine.

They had mounted a search and rescue operation that involved a rescue helicopter and boat attempting to reach us for over four hours. In hindsight, we think we heard the helicopter, but the cloud ceiling was too low for us to see it. We didn’t see any other boats, but that’s not surprising considering that our attention was focused on each other and the tasks at hand.

Finally, the Coast Guard contacted the outfitter where our float plan was being held. They had probably realized we were OK and just met us at the landing to complete their report. Next time, I’ll contact the local authorities first and tell them what we plan to do—that it might look like trouble, and that we have a marine radio and cell phone to contact them if a true need arises.

The Coast Guardsmen told us that at one point their helicopter spotted us but then lost us. Although the Triangle isn’t that big, they couldn’t establish our position well enough to effect a rescue or even make contact. A USCG boat was sent out, but the conditions near the Triangle were too rough and would have made a rescue difficult. As well-trained as rescuers might be, you can’t expect to be rescued everywhere, even when right next to a populated island with coast guard rescue crews on hand. It’s important to have the skills and the equipment to be self-sufficient.

Aftermath

Mick, the kayaks and I came through in pretty good shape. I discovered that I had a cut on my neck that looked like it was made by the edge of a paddle blade. We surmised that it occurred during some of our early rescue practice. I recall being smacked by the paddle a few times but didn’t realize it had done any damage. The deck lines and bungees on both kayaks had been damaged. We replaced them with a number of independent lines to avoid losing all function if a single continuous perimeter line or a single crisscrossed bungee were to break. With multiple shorter lines, if one section fails, an alternate is not far away.

Our paddle leashes were essential. A good leash will have quick-releases on both ends that could easily be operated by feel. Although we hadn’t needed it that day, a knife accessible by either hand at any angle would have been essential if an entanglement with the paddle leash or other cordage couldn’t have been undone without cutting. After our Triangle experience, I now always carry one on the front of my PFD that I can reach with either hand.

I have an extensive history of motion sickness, so I wear anti-seasickness wristbands whenever I expect any rough water. I was pleased with the success of these simple acupressure bands. If you might not normally have trouble with motion sickness, focusing on the deck of a heaving boat for extended periods of time can take you into totally new and debilitating territory.

The Voice of Experience

Plan for the worst. If you’re separated from your boat and paddle, you’ll have only what you’re wearing and carrying on your body. Any critical safety gear securely stowed in the kayak or on deck is useless if you aren’t with the boat. And you need your own gear. You can’t rely on your buddy’s. Secure everything and carry spares of anything essential.

Know your gear. If you have the possibility of challenging conditions, don’t add new gear into the mix unless testing it is your intent. When learning to paddle a new boat, increase your difficulty of conditions gradually so whatever surprises it might hold are manageable.

Know your paddling partners. It’s important to know the limitations of your buddies and how they react under stress. Had either Mick or I panicked or even just quit trying, our day would have turned out much differently.

A Useful Adventure

We lost an expensive carbon-fiber paddle, a chart and a dry bag of emergency gear, and the deck rigging on both boats was damaged. And yet this was the best day of paddling I’ve ever had. I learned more about myself and paddling in one day than in the several years since I had taken up sea kayaking. I was able to enjoy it because I’d been rational and realistic in my pursuit of adventure. Mick and I chose to kayak wisely but not be overly conservative. We both learned a lot by pushing our limits a bit. Our day in the Triangle was not only a great adventure, it provided us with a wealth of experience to help us improve our gear and our techniques.

I had decided to go kayaking after work one day, and that morning, I’d carefully loaded my kayak onto my cartop racks, strapped it down and tied bow and stern lines to the car. I had driven 15 miles, including several miles on the freeway, and I was only one stoplight away from work. As I pulled forward in the line of waiting cars, I heard what sounded like a horrific automobile crash. The front of my boat lurched down toward the hood of my car, and small pieces of fiberglass floated down like falling snow sprinkling my -windshield.

I had decided to go kayaking after work one day, and that morning, I’d carefully loaded my kayak onto my cartop racks, strapped it down and tied bow and stern lines to the car. I had driven 15 miles, including several miles on the freeway, and I was only one stoplight away from work. As I pulled forward in the line of waiting cars, I heard what sounded like a horrific automobile crash. The front of my boat lurched down toward the hood of my car, and small pieces of fiberglass floated down like falling snow sprinkling my -windshield.

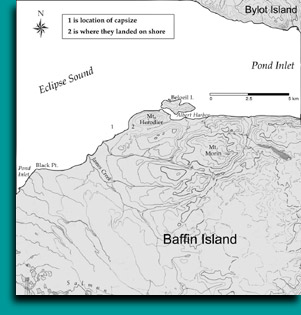

By 2:30 the kayaks were back in the water. Marilyn and Rosemary both had been experiencing some lower back discomfort and so they both improvised backrests using sweatshirts wrapped in plastic bags. They were looking forward to reaching Mt. Herodier and rest. A French couple—Elizabeth Mitchell (originally from Canada) andPascal Ertlé—had left Pond Inlet in a double kayak at 2:00 that day headed for the same campsite area (as a jump-off point to Bylot Island). They had spoken with the four Canadians back in town and had watched them load their gear down at the beach. It didn’t take long for the experienced duo to overtake the group. By then they had the impression that the four Canadians might not be adequately prepared for Arctic paddling. Only Elizabeth spoke English. She wanted to express her concern that the four kayakers were paddling too far from shore. Noting the idyllic conditions and not wanting to stick her nose into the other people’s business, she just bid them farewell as they parted company.

By 2:30 the kayaks were back in the water. Marilyn and Rosemary both had been experiencing some lower back discomfort and so they both improvised backrests using sweatshirts wrapped in plastic bags. They were looking forward to reaching Mt. Herodier and rest. A French couple—Elizabeth Mitchell (originally from Canada) andPascal Ertlé—had left Pond Inlet in a double kayak at 2:00 that day headed for the same campsite area (as a jump-off point to Bylot Island). They had spoken with the four Canadians back in town and had watched them load their gear down at the beach. It didn’t take long for the experienced duo to overtake the group. By then they had the impression that the four Canadians might not be adequately prepared for Arctic paddling. Only Elizabeth spoke English. She wanted to express her concern that the four kayakers were paddling too far from shore. Noting the idyllic conditions and not wanting to stick her nose into the other people’s business, she just bid them farewell as they parted company. If you’re into making your gear do double duty, you can add a matching female buckle half to the end of one of the side anchoring straps, and you’ll have a first-rate fanny pack. The foam sewn into the bottom of the Turtle Back for flotation makes it quite comfortable when it’s worn around the waist.

If you’re into making your gear do double duty, you can add a matching female buckle half to the end of one of the side anchoring straps, and you’ll have a first-rate fanny pack. The foam sewn into the bottom of the Turtle Back for flotation makes it quite comfortable when it’s worn around the waist.  The Wheeleez tires aren’t as free rolling on pavement as other wheels, but they are certainly the quietest. They don’t transmit any vibration to the kayak.

The Wheeleez tires aren’t as free rolling on pavement as other wheels, but they are certainly the quietest. They don’t transmit any vibration to the kayak.

can be hard to pick out from the background, and it’s their motion that makes them stand out. Beyond 75 yards, the Ion blades fade into invisibility. The blades will continue to glow all night long, and after you get to camp, they make a great bedside “table” for your flashlight, glasses and other things that the tent fairy often hides after you’ve fallen asleep.

can be hard to pick out from the background, and it’s their motion that makes them stand out. Beyond 75 yards, the Ion blades fade into invisibility. The blades will continue to glow all night long, and after you get to camp, they make a great bedside “table” for your flashlight, glasses and other things that the tent fairy often hides after you’ve fallen asleep.

The suit is comfortable to wear and mates well with a spray skirt. The back-entry zipper makes the suit easy to get on and off, and it doesn’t clutter up the front of the suit. The suit lends itself well to the range of motion required by paddling and rolling. The ends of the zipper do, however, press against the backs of your arms while you’re paddling. It may feel strange and slightly annoying at first but is soon forgotten. That the Aleutian keeps you dry is to be expected. In its details—the right materials for the job in the right places—are the reminders that the Aleutian EXP is money well spent.

The suit is comfortable to wear and mates well with a spray skirt. The back-entry zipper makes the suit easy to get on and off, and it doesn’t clutter up the front of the suit. The suit lends itself well to the range of motion required by paddling and rolling. The ends of the zipper do, however, press against the backs of your arms while you’re paddling. It may feel strange and slightly annoying at first but is soon forgotten. That the Aleutian keeps you dry is to be expected. In its details—the right materials for the job in the right places—are the reminders that the Aleutian EXP is money well spent. The bottom of the cagoule has a circumference of roughly 105 inches and should fit even the larger coamings of touring kayaks. In our tests, the cut of the cagoule made for a good fit over the spray deck without any excess fabric. Having the extra layer on didn’t get in the way of paddling or even rolling. Keep in mind you shouldn’t cover the spray skirt grab loop with the cagoule.

The bottom of the cagoule has a circumference of roughly 105 inches and should fit even the larger coamings of touring kayaks. In our tests, the cut of the cagoule made for a good fit over the spray deck without any excess fabric. Having the extra layer on didn’t get in the way of paddling or even rolling. Keep in mind you shouldn’t cover the spray skirt grab loop with the cagoule.