Jammed in the cockpit and starting to suck in water, I was on the verge of blacking out. Fortunately, two good Samaritans watching from the road rushed down to the shoreline to help me.

In the wake of a 960-millibar low-pressure system passing southern Vancouver Island, an intense westerly winter wind kicked up a mean chop off the Victoria, B.C., waterfront. I was eager to take advantage of the churning water and clear skies to refine my rough-water paddling technique.

The duration and intensity of the gusty winds made paddling more difficult than I had anticipated. Although the bay was wide enough to provide a safe, secure catch-basin for me if I were forced to do a wet exit, paddle and boat control grew increasingly trying, so I decided to surf in and wait for the wind speed to drop.

A blast of wind pushed me dangerously close to a shallow lee-shore headland at the edge of the pebbled beach lining the bay. Unable to turn into the wind to move back into the middle of the bay, I tried riding in to shore on the back of a four-foot wind-wave. I had taken aim at a relatively navigable section of the shoals around the point, when the stern of my kayak was suddenly and steeply lifted by an unusually large wave. Before I could lean back, the bow buried deep into the trough and hit the rocky bottom. The force of the impact broke the foot bar and drove my legs and hips deep into the cockpit.

When I found myself hanging upside down, I felt a moment of relief because I was wearing my surf helmet, but then I discovered that being twisted in the cockpit threw off my set-up for rolling. Out of air, I released the spray skirt and attempted a wet exit but was unable to extricate myself from the cockpit. I was both surprised and annoyed that I couldn’t exert enough leverage to push myself out of the cockpit. The waves pushed me into a narrow, shallow surge channel where I didn’t have enough space to try to roll or scull to the surface for air.

Panicking, I let go of my paddle to push off the rocks while desperately trying to pull myself up for air in the lull between the back-and-forth surging of the cold sea. Jammed in the cockpit and starting to suck in water, I was on the verge of blacking out. Fortunately, two good Samaritans watching the storm from the road above the beach rushed down to the shoreline to help me.

That was almost 20 years ago, but I can still recall the sense of helplessness and despair I felt the moment I realized I was trapped in my kayak.

Entrapment Defined

Entrapment is a hazard more commonly associated with whitewater kayaking than with sea kayaking. A whitewater kayak, pinned against an obstruction in the river, could be folded by the force of the current. The collapse of the kayak puts a vice-like grip on the paddler’s legs. Most whitewater kayaks manufactured today have foam pillars to prevent collapsing and large keyhole cockpits that let kayakers eject quickly by simply pulling up their knees.

Coastal kayakers aren’t likely to be caught in a collapsed hull, but there are a number of other situations that prevent a quick and safe wet exit. A capsized paddler who is stuck in the cockpit and unable to roll or get to the surface for air is at serious risk of drowning. There are a variety of causes of entrapment in sea kayaks: forces of nature, medical or disability complications, ignorance of technique, spray skirts that can’t be released, inexperience and entanglement with gear. Entrapment is also caused by equipment failure, forgotten procedures and simple panic or lack of preparation. Even experienced paddlers, especially those with closed-cockpit kayaks, have to be wary of circumstances that might lead to risk of entrapment.

The causes of entrapment are usually easy to identify after the fact but often catch paddlers by surprise. There are ways to prevent potential problems and ways to prepare and practice for self-rescue in the event of an entrapment. Over the past few years, there have been a number of entrapment incidents. Some simply caused embarrassment; others were frightening, life-threatening close calls. For some, the substantial stress of an entrapment led to abandoning sea kayaking as a sport. In a few cases, there have been fatalities. Entrapment may not be common, but it is a matter worthy of our awareness and preparedness.

Novice Kayakers

Entry-level paddlers are particularly vulnerable to the untoward aftermath of capsizing. Unfortunately, an unreasonable fear of suddenly submerging and subsequently getting stuck in a kayak may actually prevent new paddlers from even practicing wet exits. Other novices-most often, those who have had no training in kayaking-may head out without even thinking about the consequences of capsizing or the procedure necessary to exit safely while inverted.

The initial stages of a capsize can be very disconcerting. Cold water can cause a painful “ice-cream headache” or, even worse, induce a gasp reflex that draws water into the lungs. Dizziness, disorientation, darkness, stinging eyes and cold, numb hands can make it rather difficult to go through the routine of releasing the spray skirt and curling out of the cockpit. Experienced paddlers learn to exhale slowly through their noses to prevent water from going up their nostrils while inverted. By keeping water out of their sinuses, they can typically remain upside down and relaxed significantly longer.

Lorne was a newcomer to sea kayaking (only first names will be used for those who have contributed their stories; names are not included for those preferring anonymity). An avid outdoorsman, he picked up an older, well-worn kayak at a garage sale. It came with a narrow-bladed paddle, a PFD and a spray skirt. He convinced a friend who was a paddler to give him a lesson at a local lake. Lorne snugged the neoprene skirt tightly around the small, wide-flanged cockpit rim while his friend issued firm directions to remain at the shore while he retrieved some items from the parking lot. Impatient with waiting, Lorne ventured out into deeper water. Without the sandy bottom to brace against, he found the boat to be very tippy. While turning the kayak back toward shore, he started to capsize. He did not know how to brace with the paddle and flailed away at the water. As his head went under, he was totally unprepared for the sting of water rushing into his nostrils.

Lorne responded as many would: with instant panic. He let go of the paddle and tried desperately to find some way to release himself from the confines of the cockpit. He tried pushing himself out with his arms, but it was as if bungee cords kept pulling him back into the seat. A strong man, he pushed with his legs but could not counter the hold of the spray skirt. He then remembered the grab loop on the spray skirt and, at the last possible moment, freed the skirt from the cockpit rim, permitting him to get out of the kayak. Lorne hasn’t been in a kayak since.

It is important that new paddlers practice wet exits in a safe, stress-free environment, with experienced and reliable help close by and ready to assist. The basics can initially be demonstrated and practiced in kayaks on shore or at the side of a pool, but they must be followed up with doing wet exits in the water. Sit-on-top kayaks (especially those with seat belts or knee straps), decked kayaks, doubles, folders and even sit-in hybrids or recreational kayaks all require wet-exit practice until novice paddlers are comfortable and adept at getting out of the kayak and maintaining control of the boat and paddle.

Some individuals can lose their composure with something as simple as placing their face in the water, so it is essential to progress to the in-water exit with someone standing alongside to assist. The first wet-exit practice sessions can be done without a spray skirt or paddle. Nose clips and facemasks are useful aids, although they should ultimately be put aside in the interest of practicing more realistic scenarios. The wet exit is a basic skill that must be mastered both physically and psychologically to effectively cope with the problems associated with entrapment.

A clean wet exit should be easy to perform and should only take a few seconds. Let the kayak come to a full rest upside down, tuck forward, release the spray skirt by pulling the grab loop forward and away from the deck, and push yourself out, keeping a grip on the paddle shaft and maintaining contact with the kayak.

Spray Skirt Fit

The improper fit of a spray skirt can lead to entrapment. Given the variety of cockpit configurations, sizes (widths and lengths), rim widths and boat materials (plastic, fiberglass, etc.), the chance for mismatch is high. Aside from proper sizing, spray skirts designed for use on plastic kayaks present a dangerous hazard when used on a fiberglass rim where they grip tenaciously. Whenever you try a new or different combination of spray skirt and kayak, make sure you can release your spray skirt with one hand. (See “Spray Skirts-In Search of the Perfect Fit,” SK, Fall ’92.) To release a tight-fitting spray skirt, you must pull the grab loop forward toward the bow of the kayak until the bungee clears the coaming flange, then away from the deck and back to release the spray skirt. If the bungee is under a lot of tension, this maneuver can require a lot of strength. Some skirts have a latex coating or a rubber rand to create a tighter seal, and both tend to be more difficult to release. These types of spray skirts are typically used by experienced kayakers who paddle in challenging conditions and have the training and strength to release a tight-fitting spray skirt, even when they are cold and tired.

Novice paddlers can use a loose-fitting nylon skirt for their initial year. It will make wet exits easier. While it may not be well-suited to more challenging conditions as the paddler becomes more competent, it can serve as a backup to a neoprene skirt or a neoprene/nylon hybrid and as an option when warm weather makes a neoprene skirt uncomfortably hot.

Incorrect Technique

Suzie was a competent paddler who had practiced doing wet exits. She had been suffering from a recent inner-ear infection when she attended a three-day sea-kayak skills upgrade workshop. During initial wet-exit practice, she rolled over and experienced a sudden and violent dizziness. In her struggle, she leaned back instead of tucking forward, slipped off the pedals and further pushed herself into the cockpit. Her class partner exited from her kayak into the deep water to assist her but was unable to exert enough leverage to help tuck her forward and release the spray skirt or right the kayak. An instructor came alongside Suzie’s capsized kayak and performed a “Hand of God” rescue (see SK, June ’00), which involves reaching underwater to pull a capsized paddler back to the surface. In this case, the instructor pulled Suzie up by the shoulder straps of her PFD. It should be noted that it would have been easier for Suzie’s partner to help if the practice had taken place in shallow water where she could have been standing next to Suzie’s kayak.

Skirt-Related Incidents

Frank, a proficient paddler, was trying out a friend’s new boat one winter. He was alone in shallow water wearing neoprene gloves and a cap and had decided to use his own neoprene skirt, which provided a tight but manageable fit on the borrowed boat. He capsized to try a wet exit. He was unable to locate the grab loop, which was located much farther forward than it would have been on his own boat. Running out of air, Frank was rather dismayed at the prospect of dying in such shallow water so close to shore. He managed to keep from panicking, and although he had let go of his paddle, he was able to swim his head to the surface, get a gulp of air, and thus gain more time to work his way out of trouble. He released the skirt by grabbing a fold of material near the edge of the coaming on one side, where the flatter curve of the coaming makes it easier to pull the bungee from the coaming flange.

The turbulence of the surf zone can make it difficult to release your spray skirt. Ron, a paddler with solid intermediate skills, was attempting to land along one of Oregon’s coastal beaches where extensive surf zones are common. He had minimal surf experience and was capsized by a large wave that ripped the paddle from his hands and dislodged him from his foot and knee braces and seat. Pinned on the back deck by the force of the wave, he was unable to reach forward to pull the grab loop on his spray skirt. Ron remained pinned for some time. He stayed calm and waited until the turbulence diminished so he could work his hands forward along the coaming to release the spray skirt. His experience highlights the need to not panic-and to grab a big gulp of air as you go over. Secondary release loops sewn to the side of the spray skirt would allow a quicker release in similar situations. (See “New Gear,” p. 52 and “Preventive Measures,” p. 54.)

Release Alternatives

Both Frank and Ron were able to avoid panic. Frank dog-paddled to the surface, where he gained enough air and therefore time to work out a solution: an alternate method for removing his spray skirt. Sometimes it can be difficult to bunch up enough of the skirt’s material when it is wet and slippery. Depending on the fit and material of your spray skirt, you can try using friction to roll the spray-skirt material edge either toward or away from your torso enough to create a fold. The best place to try this is near your hips where the spray deck is narrower. Gather the wrinkle that forms, pinch it between your thumb and fingers, then pull outward and off the coaming. On a tight-fitting skirt, place your fingers under the coaming if the recess allows this, then pinch the skirt’s material as above, with your thumb on top of the rim, trapping the material. You may need to use your other hand to reach across for leverage to pull the skirt off (tuck your paddle under your arm if it isn’t connected by a tether). With a non-recessed coaming built high off the deck, you may be able to pry the skirt out from the underside of the coaming with your fingers. If you have a skirt that uses an adjustable bungee-usually protruding from the rear of the skirt-you should be able to reach back and use this as an alternative grab loop.

Depending on the arrangement of your spray skirt, paddling apparel and PFD, you may be able to reach down through the waist tube of the spray skirt to release the skirt. If you wear your PFD on the outside of your spray skirt, you will need to slip your hand under the bottom edge of the PFD, reach up over the top of the skirt’s tube and then slip your hand downward through the tunnel. Lift the spray deck’s underside and push it out beyond the lip. You may need your other hand to help peel it from the coaming.

It may also be possible to slip out of the spray-skirt waist tube, leaving the spray skirt attached to the kayak. This can be very easy to do with zippered models-just unzip and slip out. If the spray skirt has suspenders, you have to release them. A rescue knife can be employed to cut an opening in the spray deck to provide something to grasp, but most paddlers.

Gloves

Your sense of touch plays an important role in finding the grab loop. Wearing paddling gloves during the off-season or in cold climates can pose challenges with locating the spray skirt’s grab loop. The layer of neoprene robs the wearer of the tactile sensitivity required to find the thin webbing release found on many spray skirts. Trying to remove gloves after a capsize eats up valuable time. Many gloves have hook-and-loop straps around the wrist, so it may be difficult to remove a glove and leave enough time to hunt down the skirt’s stock grab loop.

In one incident, a victim who nearly drowned and was subsequently hospitalized indicated she was lucky to be alive only because her paddling partners reached her in time to provide assistance-the thick neoprene gloves she was wearing made it impossible for her to release herself in a timely manner. They had unexpectedly deprived her of her sense of touch, leaving her helpless.

In another case, an east-coast paddler by the name of Chris was trying out a friend’s new composite boat and using a borrowed spray skirt. Chris and several other experienced paddlers were playing in refracted waves, all wearing neoprene gloves and hoods. Upon capsize, Chris gave up on his roll and attempted to find the grab loop. On his own skirt, the grab loop was to the front and fitted with a carabiner that not only made it easier to locate by touch but also made the strap hang away from the boat where it was easy to find. On the borrowed skirt, the release was a plain nylon strap offset to the right. Chris reached forward to where he would have found the grab loop on his own boat and grabbed at the foredeck bungee cords instead. He tried pushing the skirt out with his knees a few times, but the skirt did not release the way it would have on his plastic boat. He continued to grope about for the grab loop but couldn’t locate it, as the neoprene gloves gave him almost no sense of touch in his fingers. Help was a long time coming in the shoaling waters, so Chris continued to keep calm and used the skirt’s mesh pocket as a handle to release the spray skirt.

In another case, a group of advanced west-coast paddlers were paddling among the rock gardens off the California coast, where the average swell was running five to seven feet that day. One of the paddlers, Patrick, was ambushed by a five-foot breaker that dragged his plastic boat completely over a boulder, dumping him upside down on the other side and headfirst into a bed of thick bull kelp. Relieved that he had not injured himself, Patrick tried to set up for a roll but found that the kelp prevented him from moving his paddle into a set-up position. Unable to roll and aware that his partners could not offer quick assistance, he attempted a wet exit but couldn’t find the grab loop. The loop was brightly colored, but Patrick’s sunglasses and the densely packed kelp stalks obscured his vision. He couldn’t remove the sunglasses without first taking the time to unbuckle and remove his helmet. When he reached though the kelp hoping to find the grab loop, he couldn’t feel it. Not only did his neoprene paddling gloves compromise his sense of touch, his hands were cold to the point of being numb.

Patrick’s Kevlar-reinforced whitewater spray skirt had a thick rubber rand around the edge, preventing him from simply forcing his way out of the boat. Running out of options and air, he knew he had to fight off the urge to panic. He had practiced Eskimo rolls and wet exits with his eyes closed, just in case of a capsize in the dark, which gave him the confidence to stay calm and maintain his concentration. But he had never anticipated the need to wet exit without having any feeling in his hands. Patrick ran his hand around the edge of the coaming until he reached the point where the grab loop was supposed to be, then closed his hand and pulled-just hoping he would have the grab loop in his grasp. He felt resistance to his pulling, and a moment later the spray skirt popped. He pushed out of the boat and clawed through the kelp to the surface.

After that incident, Patrick used a couple of electrical ties to attach a Whiffle-ball to the end of his grab loop to serve as a locator device. He now practices while wearing paddling gloves to make the conditions more realistic. The loss of sensation in your hands can be attributed to thick gloves and numbness from cold water or prolonged exposure to wind. Pogies, fingerless gloves or thin neoprene “blister” gloves can provide the required protection from cold and may preserve some tactile sensitivity. Regardless of what you might wear on your hands, a solid contact point on the release loop is essential for cold-water paddling.

Trapped Grab Loops

Many of us have experienced a very common problem: unintentionally securing the spray skirt with its grab loop tucked under, hanging useless inside the cockpit. Most of the time, the problem is noticed and corrected before leaving the shore. A trapped grab loop is an accident waiting to happen. Ensuring your spray skirt grab loop is fully exposed and free from entanglement should be part of everyone’s pre-launch ritual. Rushing to attach the spray skirt prior to launching through surf and simple forgetfulness are common causes for leaving the grab loop trapped under the spray skirt. Although entirely preventable, it does happen, and because it is such an easy mistake to make, all paddlers should practice alternative methods for releasing their spray skirts without using the grab loop.

In an informal rescue practice session held half a mile off the California coastline, Stephen had borrowed a river kayak that was tight for his large frame, as his kayak was in for repairs. He capsized to practice rolling but failed to roll up. He banged on the hull, indicating his need for a bow rescue. His spotter set his bow alongside and Stephen started to pull himself up on it, but accidentally pushed his spotter’s boat away in the process. Out of air, Stephen reached for his skirt’s grab loop, which had inadvertently been tucked under the tight rubber rand. With his thighs wedged tightly in the kayak’s knee braces and the footpegs not adjusted properly for his height, he couldn’t even try a forced exit. Stephen banged vigorously on his hull and another paddler presented a bow for Stephen to pull himself up on.

Gear Failure

A number of paddlers told of wet exits that went awry because of gear failure. Spray-skirt materials are often weakened through repeated use, exposure to UV damage and the effects of salt crystallization. Saltwater and sunlight aren’t the only environments rough on gear. Rescue practice in swimming pools and the chlorine in the pool water can be especially hard on spray skirts. Savvy paddlers typically use a second skirt for pool practice sessions to keep from weakening the skirt they use when paddling. It is also important to practice good in-season care of your gear, drying it between uses and keeping it free from mildew. As a preventive measure, paddlers should ensure that their gear, including spray skirt, is rinsed with fresh water after every trip (see “Gear Preparedness: Paddling at the Drop of a Hat,” SK, Oct. ’01) and inspect their equipment for wear or weakness.

A few years ago, I went with two friends on a remote off-season paddle, battling snow and a building gale on a long crossing. One of my partners needed to retrieve a piece of gear from his cockpit before conditions deteriorated further. When he tried to pop off the spray deck, the release loop on his aged skirt tore off completely. He was shocked by the failure of this critical piece of his spray skirt and concerned by the complication this could present in the event that he needed to wet exit. Realizing his predicament was a serious one, we all stayed very close to one another for the rest of the crossing.

Two paddlers, Rich and Bill, were paddling on Lake Michigan in the fall. Though the air temperature was hovering at 20°F, the men were feeling warm from exertion in their dry suits and pogies. While they were crossing over a sandbar, breaking waves capsized Rich. Taken by surprise, he decided to wet exit. He pulled on his grab loop, but it tore off in his hand. He started to peel the spray deck off without the loop, but the spray skirt was iced to the cockpit rim! With a feeling of desperation, he peeled the skirt’s rubber rand back a few inches at a time with numb fingers. Rich was finally able to exit. Bill estimated that it took over a minute to make that wet exit.

New Gear

It is easy to imagine that well-used gear may fail, but it is less obvious to expect that new gear may cause entrapment. During a course held in the Pacific Northwest, students were learning rescues and exits and practicing paddling in the fast-moving water of Deception Pass. One of the students flipped over and was unable to right herself. She was using a new neoprene skirt that was still very tight, requiring the release loop to be pulled forward, then out and back. She attempted to release the skirt a number of times, without success. A new compass had just been installed on the front deck, which did not allow enough distance to pull the loop forward to release the skirt off the front lip of the coaming. The rubber rand was so new and so snug, pulling it straight up and back did not work. The lead instructor immediately recognized the telltale signs of a capsized paddler in distress. He quickly came alongside the overturned kayak, reached underwater and did a successful “Hand of God” rescue before the student ran out of air.

Any time you modify your kayak or add new gear to it, practice wet exits and reentry drills in a controlled setting. Have an able partner standing by to assist you. Any deck gear items, including deck bags, mounting apparatus, sail masts and items such as strapped-on gear or photographic equipment and cases, can all interfere with a smooth wet exit.

You can incorporate a backup release device. A strap anchored to the underside of the foredeck and set over the coaming before the spray skirt is attached will work effectively as an auxiliary release even on a tight spray skirt. (See “Easy On, Easy Off,” a review of the Kayak Safe release strap, SK, Oct. ’96.) Of course, you have to make sure the strap is draped over the coaming before attaching the spray skirt.

There are skirts that come with straps that run across the spray-skirt deck and are sewn to the bungee or rand. Some manufacturers will accommodate this customization upon request. The straps won’t release the skirt as efficiently as a front-release strap because you’ll have to work the bungee free from the front of the coaming, but a good tug is all that is required to start the spray deck curling back over the coaming.

Footwear

There were many incidents brought to our attention that involved paddlers getting snagged on footpegs. Shoelaces and sandal straps both have the potential to snag foot braces. Recent offerings in footwear designed specifically for paddlesports have addressed this problem by covering or eliminating straps and laces. Think through your choice of footwear and test them in the kayak while on dry land for entanglement dangers. Shoelaces create a potential danger by forming loops that can catch around a rudder pedal. Sandals, especially those with only two or three straps, can let a footpeg slip between the foot-bed and sole of the foot. Footpegs can also hook between one of the top straps and the top of your foot. Sandals that cover more of the foot are less likely to catch in this manner. Some tour company trip coordinators, having experienced problems with clients exiting their kayaks, inspect and restrict what kind of footwear their clients can wear while paddling.

Some types of boots have ankle draw cords that are frequently responsible for entrapment problems. Some class instructors request that students cut off the excess cordage to remove the loop and relocate the knot to minimize exposure.

If you find yourself snagged by your footwear, try slipping back into the cockpit to release the tension on the snag and coax it free. If that doesn’t work, try to pry off the snagged shoe by using your other foot to push the heel off and free yourself.

Paddlers who use a bulkhead foot brace or a sea sock have less of a concern with potential footwear entrapment. In the case of my entrapment in the opening story, the foot-bar in my kayak was designed to pivot back toward the paddler during a wet exit in the event of a foot getting lodged behind it. Unfortunately, the impact forced it forward, jamming me in the cockpit. Following that incident, I removed the original bulkhead, fabricated a new one and installed it closer to the foot-bar to reduce the chances of my being pushed forward of the bar.

A few years ago, Orval, an avid paddler, was teaching his daughter Maggie how to do a wet exit. They were practicing in a small lake. Maggie is a tall girl and a strong swimmer. She began her wet exit even before the kayak was completely upside down, but the ankle draw cord of one of the booties she was wearing got caught on a footpeg. Orval lifted her to the surface and, with the help of Maggie’s mom, managed to get her free. Maggie continued to pursue the sport, but no one in the family takes it for granted that gravity alone will provide for a graceful exit.

Surfing invariably places a paddler at greater risk for entrapment. In one case, Bill, a reasonably experienced whitewater and sea kayaker, was surfing along the Pacific Rim National Park. He was working his way through some moderately large dumping waves near the outer break when he high-braced into a breaking wave and broke the shaft of his wooden paddle. The force of the wave shifted Bill’s seat and foot positioning sufficiently enough to shove him toward the bow. A loop in one of the laces of his running shoes caught fast on the foot brace. When he released the spray skirt, he realized he was trapped. After an inordinately long time under the water, Bill was finally able to pry off the offending shoe with his free foot and pop to the surface. Back on shore, he breathed deeply, happy to be alive. It was 15 years before Bill returned to the surf zone, and only after he received further training and a pair of reef booties.

New Gear

Other Entrapment Experiences

There have been a number of incidents involving a miscellany of things leading to entrapment. Wallets in back pockets have caught on seats (the individuals obviously weren’t planning on getting wet!), wetsuit kneepads have snagged on thigh braces and dry-suit pockets have hooked on rudder-cable adjusters. Tethered emergency bailout packs stored in the cockpit and pullout foam bulkhead spacers have caused entanglement, and gear located behind seats has come loose during wet exits. Sewn stops on the ends of webbing and loose fitting or poorly adjusted PFDs have caught on the deck, and pant-leg draw cords have snared on pedals.

I was conducting a sea kayak surf course for a local club in the spring. After the session was over, I tried out my spouse’s recently acquired kayak. When I tried to lean forward to surf on a wave, something held me firmly back. A bit unnerved, I called a student over to inspect the rear deck. The knotted end of a PFD draw cord had entangled on the back deck. It would have prevented my doing a wet exit. The student dislodged the snag, and I promptly returned to shore to study the problem and make sure it wouldn’t happen again.

Another paddler was escorting a novice when seas grew to four or five feet. The new paddler wisely elected to walk back along the shoreline to the put-in, while the experienced paddler towed the empty kayak the few miles back. Seas continued to build until the paddler found himself towing the empty kayak through heavy surf. An eight-foot wave reared unexpectedly in the impact zone, causing the kayak to tumble and the towline to wrap around the kayak and the paddler’s arms. He had just enough flexibility left to release the skirt and bail out.

In one particularly frightening incident, a paddler reported he was having some fun doing a little solo surf practice in his sea kayak. It was no surprise to him when he capsized. He missed his roll and decided to bail out. After releasing the grab loop, he attempted a wet exit but was unable to get out of the cockpit. It became quickly apparent that the carabiner of his PFD’s integral tow belt had somehow clipped itself onto his kayak’s perimeter deck line. In the turbulence of the surf zone, it was very difficult for him to unclip the carabiner. It became a desperate, life-threatening situation. He was finally able to unclip himself during a lull in the breaking waves. You can eliminate this type of entanglement by removing deck lines that run along the sides of the cockpit. They aren’t necessary, since you have the cockpit coaming to hang on to if you are in the water alongside the middle of the kayak.

In another case, Steve, a very experienced paddler, had just outfitted the cockpit of his Greenland-style kayak with neoprene bracing. It made for a tight fit, requiring him to squeeze his thighs under the coaming. During rolling practice, Steve capsized and somehow was unable to get his knees into the normal position for rolling. Low on air, he attempted to bail out, but the friction created between his wetsuit and the new neoprene padding prevented him from slipping out. On the verge of panic, Steve managed to pry one leg out with his hands, then the other. After trying to achieve a looser fit by thinning the neoprene padding, he eventually chose to replace the neoprene outfitting with the more common minicell foam that had less grip when it was wet, yet provided good contact between his legs and the boat. Reconfiguring your cockpit, outfitting it for better boat control, installing interior cargo nets and inner cockpit bags or knee tubes/thigh braces, changing seats and back rests, adding heel pads to the inner hull and adding pumps are all worthwhile modifications, but the potential for entrapment must be considered. Make sure your modifications do not inhibit you from being able to perform a wet exit smoothly.

Preventive Measures

If the spray-skirt manufacturer hasn’t already added a toggle or clear tube section to the grab loop, it is a good idea to modify it yourself. The normal webbing loop for releasing the spray skirt can be difficult to find when you are underwater, disoriented and anxious. Paddlers have employed a number of modifications to make the release easier to find by touch, including golf Whiffle balls (like the one used by Patrick), dowels, beads and large knots. A carabiner clipped into the webbing loop has the advantage of hanging down in front of the paddler when the kayak is inverted. (A locking carabiner is recommended because it is less likely to inadvertently snag the paddler or become detached.) Even wrapping the webbing loop tightly with brightly colored electrical tape is an easy solution that makes the loop more visible and solid to the touch.

Most of these modifications also make it less likely that the strap will get tucked accidentally under the skirt, causing a dangerous situation. Since you might not be able to see the loop in murky or aerated water, you should be able to locate and pull your release handle by touch alone even when you are wearing thick gloves or have cold hands.

Backup Methods

It’s not a bad idea to have at least one or two backup methods that get your head to the surface where you can get some air. Rolling, of course, is a good solution to a capsize, but if you are doing a wet exit, it is usually because you are unable to roll. If you carry an inflated paddle float or, better yet, a rigid paddle float under the bungees on the back deck within easy reach, you can pull it out and use it to roll up or just get your face above the water (See “Please Remain Seated,” SK, Summer ’90). The BackUp rescue aid (www.roll-aid.com) is a CO2-inflated float that you can rapidly deploy to pull yourself up to the surface with minimal effort. There are also breathing tubes and air-supply devices on the market, but these work best for a calm and well-practiced kayaker.

Developing the ability to scull your way to the surface with your paddle, even if only partially, is an invaluable skill. (See “Vertical Storm Roll,” SK, Dec. ’01.) By extending your paddle and sweeping out sideways and back to the stern, you can gain tremendous leverage and perhaps a breath of air while you reevaluate possible solutions to your entrapment situation. Developing the ability to swim to the surface on either side of the kayak is a skill that you can add to your survival strategies, and it doesn’t rely on having extra equipment.

It is also prudent to paddle with a partner (or partners) who exhibits a good level of awareness and can maneuver quickly to your aid if necessary. The “Hand of God” rescue is a technique that can be used if a capsized paddler fails to wet exit. If you don’t have the strength to right the capsized paddler, bringing the paddler up for air is enough. Then you can help pry the skirt loose, if that is the problem. Never assume that someone who has capsized is just hanging around upside down for the fun of it. They may be entrapped or suffering from some other complication. Start moving toward the capsized kayak as soon as you see it go over. Knowledge of CPR and other aquatic lifesaving skills is always an asset wherever you are.

Common Sense

Entrapment is a serious situation. There have been fatalities where the victims were found still seated in their kayaks, spray skirts in place. A capsized paddler who can’t get to the surface may be able to go a minute and a half on a lung-full of air at best. Add panic and attempts to struggle free from an entrapment, and it doesn’t take long for CO2 levels to build quickly and oxygen supplies to deplete.

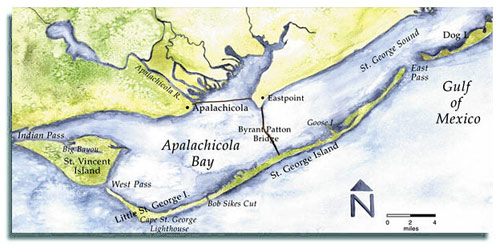

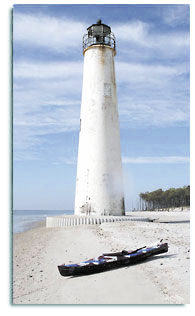

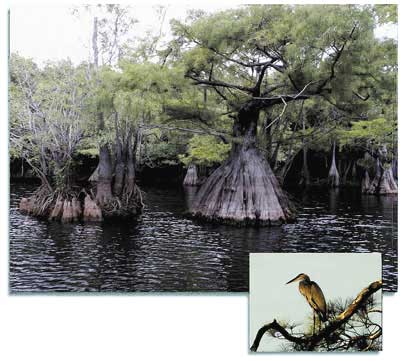

Another great side trip, which you can take in place of or in addition to the paddle to the Cape St. George lighthouse, is to explore the chain of four interconnected lakes at the eastern end of St. Vincent Island. About midway along the broad end of the island is a collection of shelters used by hunters during the deer and pig hunts that are permitted on the refuge in the fall. Near these shelters is a tidal creek that connects with the lakes. The creek is too small and winding for large touring kayaks but can easily be navigated by smaller, recreational kayaks. Touring kayakers can leave their boats on the beach and explore the lakes along a system of trails that is not marked but is easy to navigate if you stick to the high ground. The island is also laced by a network of sand roads, formerly used by loggers. The roads are numbered and lettered (numbered roads run north-south and lettered roads run east-west), and frequent signage makes it relatively easy to navigate the island.

Another great side trip, which you can take in place of or in addition to the paddle to the Cape St. George lighthouse, is to explore the chain of four interconnected lakes at the eastern end of St. Vincent Island. About midway along the broad end of the island is a collection of shelters used by hunters during the deer and pig hunts that are permitted on the refuge in the fall. Near these shelters is a tidal creek that connects with the lakes. The creek is too small and winding for large touring kayaks but can easily be navigated by smaller, recreational kayaks. Touring kayakers can leave their boats on the beach and explore the lakes along a system of trails that is not marked but is easy to navigate if you stick to the high ground. The island is also laced by a network of sand roads, formerly used by loggers. The roads are numbered and lettered (numbered roads run north-south and lettered roads run east-west), and frequent signage makes it relatively easy to navigate the island.

In our February 2000 issue, we did an article on the various things a personal desk accessory (PDA) can do to make itself useful on kayak trips. There are programs available for tide tables, navigation, note taking and games, in addition to the PDA’s built-in features. The big drawback to using a PDA aboard a kayak is its lack of waterproofing. A splash of water, and it’s bye-bye data.

In our February 2000 issue, we did an article on the various things a personal desk accessory (PDA) can do to make itself useful on kayak trips. There are programs available for tide tables, navigation, note taking and games, in addition to the PDA’s built-in features. The big drawback to using a PDA aboard a kayak is its lack of waterproofing. A splash of water, and it’s bye-bye data.

Five weeks later, within a day’s paddle of the Brooks Peninsula, Robyn’s forearms are beginning to scream. Each of us has suffered through aching backs, sore arms and cramping butt muscles, but nothing has been as painful as this. In the last few miles of the paddle, Kris and I both offer to tow her or switch her into the double, but she firmly and persistently paddles on. Forearms are one thing you cannot do without on a sea kayak trip. We land at Restless Bight and wait a day for gales to blow over, a day for Robyn’s arms to rest. To the south, the mountainous Brooks Peninsula juts nine miles out from Vancouver Island. Fishermen we met two weeks earlier told us stories of cats-paws swirling out of the sky there and whipping water into the sky, capsizing fishing boats.

Five weeks later, within a day’s paddle of the Brooks Peninsula, Robyn’s forearms are beginning to scream. Each of us has suffered through aching backs, sore arms and cramping butt muscles, but nothing has been as painful as this. In the last few miles of the paddle, Kris and I both offer to tow her or switch her into the double, but she firmly and persistently paddles on. Forearms are one thing you cannot do without on a sea kayak trip. We land at Restless Bight and wait a day for gales to blow over, a day for Robyn’s arms to rest. To the south, the mountainous Brooks Peninsula juts nine miles out from Vancouver Island. Fishermen we met two weeks earlier told us stories of cats-paws swirling out of the sky there and whipping water into the sky, capsizing fishing boats.