Cascade Designs patented the self-inflating mattress idea in the 1970s, and lots of campers gladly traded in their closed-cell foam pads for the greater comfort of a Therm-A-Rest pad. The downside is that the Therm-A-Rest pad, like any air mattress, is vulnerable to punctures. A pinhole leak will leave the sleeper on the cold hard ground. The ToughSkin pad from Therm-A-Rest adds a bit of closed-cell foam inside a Therm-A-Rest pad to provide a measure of puncture resistance. The fabric on the bottom of the pad is fused to a sheet of -inch closed-cell foam, which is in turn fused to the usual layer of open-cell foam. If a thorn, sharp twig or rock shard punctures the bottom fabric but doesn’t completely penetrate the closed cell foam, the airtight integrity of the pad won’t be compromised.

Cascade Designs patented the self-inflating mattress idea in the 1970s, and lots of campers gladly traded in their closed-cell foam pads for the greater comfort of a Therm-A-Rest pad. The downside is that the Therm-A-Rest pad, like any air mattress, is vulnerable to punctures. A pinhole leak will leave the sleeper on the cold hard ground. The ToughSkin pad from Therm-A-Rest adds a bit of closed-cell foam inside a Therm-A-Rest pad to provide a measure of puncture resistance. The fabric on the bottom of the pad is fused to a sheet of -inch closed-cell foam, which is in turn fused to the usual layer of open-cell foam. If a thorn, sharp twig or rock shard punctures the bottom fabric but doesn’t completely penetrate the closed cell foam, the airtight integrity of the pad won’t be compromised.

We tested the pad by pushing a safety pin at a shallow angle through the fabric, into the foam and back out the fabric again. After making several holes this way, we submerged the inflated pad, checked for leaks and holes, and squeezed the pad. There were no bubbles coming from the holes even when we squeezed the pad hard to create some pressure. We also set the pad on the floor, piled some weights on top of it and left it there. After two days, the pad was still fully inflated.

If you do happen to get a puncture through the foam and the pad leaks, at least you’ll have the closed-cell foam to provide some measure of insulation, perhaps enough to get you through the night. Repairs to the ToughSkin pad are the same as they are with other Therm-A-Rest pads, using the repair kit available separately from the manufacturer. The addition of the closed-cell foam adds only a bit more bulk. In the small size, the pad rolls up to a diameter of 4 _ inches—an inch more than the standard pad of the same length.

Chinook PFD by NRS

The Chinook is a cross between a PFD and a fishing vest and has as many cubby-holes as an old roll-top desk. There are 10 pockets, five on each side. The lower pockets are stacked three deep: a Velcro-flapped pleated pocket, a zippered box pocket and a zippered pocket that lies flat against the body of the PFD. The top pockets have a Velcro closure panel pocket on top of a zippered box pocket. With the exception of the two inner pockets at the bottom, the pockets have either grommet or mesh drains. (Those two inner pockets are flat, so they can’t take on much water and will slowly drain through the stitching.) The zippers on the four boxed pockets are positioned so that you can easily peer into those pockets. If you run out of room, there are five attachment points along the zipper. The upper-left pocket has a patch of Velcro pile designed to hold fishhooks.

The Chinook is a cross between a PFD and a fishing vest and has as many cubby-holes as an old roll-top desk. There are 10 pockets, five on each side. The lower pockets are stacked three deep: a Velcro-flapped pleated pocket, a zippered box pocket and a zippered pocket that lies flat against the body of the PFD. The top pockets have a Velcro closure panel pocket on top of a zippered box pocket. With the exception of the two inner pockets at the bottom, the pockets have either grommet or mesh drains. (Those two inner pockets are flat, so they can’t take on much water and will slowly drain through the stitching.) The zippers on the four boxed pockets are positioned so that you can easily peer into those pockets. If you run out of room, there are five attachment points along the zipper. The upper-left pocket has a patch of Velcro pile designed to hold fishhooks.

The Chinook has two side cinches in addition to a waist belt. The back has its foam panel placed up high, above a mesh panel that supports the cinch straps and waist belt. The configuration at the back keeps the PFD from hindering layback rolls.

The Chinook has two side cinches in addition to a waist belt. The back has its foam panel placed up high, above a mesh panel that supports the cinch straps and waist belt. The configuration at the back keeps the PFD from hindering layback rolls.

If you subscribe to the theory that our working memory maxes out when dealing with more than seven (plus or minus two) elements, we suggest that you leave at least one pocket empty.

Emergency Shelter by Expedition Essentials/Sea Kayaking USA

Lots of animals huddle together for warmth—musk oxen, penguins and bees all do it—but unfortunately, social mores prevent many of us from spooning with our paddling mates. So if we come ashore for a lunch break during a winter outing, it won’t be long before we’ll want to be paddling again just to warm up. The Emergency Shelter from Expedition Essentials can make it possible to huddle up for warmth without encroaching too much on anyone’s “personal space.” The Emergency Shelter is an update on an old concept and uses lightweight paragliding material to make a bag big enough to cover four people.

It’s an effective barrier against the wind, but it isn’t breathable. It may get a bit clammy inside as the humidity goes up, but fortunately the evaporative heat loss from your skin or wet clothing is slowed. The fabric repels water but isn’t entirely waterproof—if you use it as a barrier between you and a wet surface, you’ll get a wet seat, but since you’re dressed for immersion (right?), it isn’t a problem.

When we tested the bag with two people inside on a 48˚F evening, the temperature inside the bag climbed quickly, reaching a very comfortable 70˚F in five minutes. The shelter has two “ports” large enough to poke your head out. There are webbing loops at the corners you could use to set the shelter up in camp to provide privacy for a camp outhouse or shower stall.

Stowed in its stuff sack, the Emergency Shelter is a compact package, about half the size of a loaf of bread, and would easily fit into a day compartment. Sure it would come in useful in an emergency, but it’s also a great refuge anytime the weather is foul.

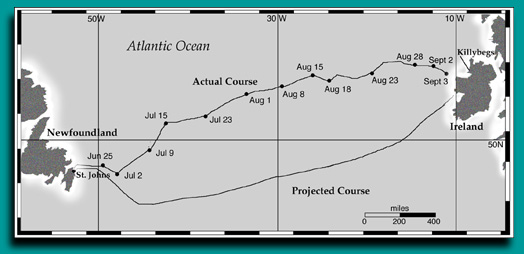

North Atlantic Challenge 2000

While kayaking round mainland UK in 1996 with a partially sighted lad, we encountered some very rough waters. One day in big seas, the bow of our 24-foot double was not touching the bottom of the trough and the stern was not touching the crest of the wave. I jokingly said that it would probably be easier to paddle the Atlantic Ocean than to endure the conditions we experienced. It was not until about six months later that I seriously considered researching the feasibility of a solo, unsupported crossing of the North Atlantic Ocean.

The following February I went to our annual canoe and kayak show where all the retailers and builders would be, and I started to plan the challenge. The show was the ideal opportunity to gain valuable contacts and seek sponsorship. However, only two companies were willing to help:one to supply the paddles and one who was interested in building the kayak, for a fee. I wanted a boat that could carry 100 days’ worth of supplies, be self-righting, that I could sleep in, and yet it should still look like a kayak.

In just two days, Jason Rice (a member of the company who built the kayak) came up with a working model. A civilian branch of the Navy, called Haslar, checked the design by using a model in simulated conditions in a special water tank to test the sea-worthiness of a ship. After successfully completing the tests, construction began. A friend put me onto a retired businessman named Jim Rowlinson. We had a meeting to discuss what I had accomplished to date. Jim was influenced by my determination and believed the project would be a success. He became the project manager, on the condition that he received no payment, and set about raising the money needed. In 1999 we travelled together to St. Johns in Newfoundland, the starting point of the journey. Through a number of contacts we were lucky to meet Linda Bartlett, who worked for the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Tourism, Culture and Recreation department. Linda was impressed by our enthusiasm and had every faith in what we were trying to achieve. She helped us immensely to fulfil our needs in Newfoundland: gear storage, accommodations, transport. Linda also introduced us to key personnel needed to help us once we arrived with the kayak. As luck would have it, there was a sea kayak symposium in Corner Brook to which I was invited to give a presentation on my planned challenge.

I decided to set off during the month of June the following year, to arrive in Irish waters before our winter started. As no onefrom the canoe and kayak show stepped forward to help with clothing, I was introduced to an outdoor clothing company, based in Scotland, that tends to specialise in mountaineering gear. They kindly offered to supply me with the apparel I needed for the challenge. Jim began to collect all of the equipment that I would require, from spraydecks to emergency kits, including a very comprehensive first aid kit. We had a special trailer built to take the kayak around the UK for trials, and ‘LandRover’ sponsored a 4×4 vehicle to tow the trailer. In order to raise financing, on these tours we gave presentations to help promote the challenge. In the eleventh hour, an Internet auction company became our main sponsor. With a secure sponsor on board, we were able to head off to Newfoundland and wait for good weather to commence the challenge.

After a couple of weeks making final preparations in Newfoundland, I got the weather that I needed: a window of five days of Westerlies. I started at about 20:00 hours as the tide was turning to help me paddle out of St. Johns. The media and a few hundred well-wishers were there to see me off. Four sea kayakers escorted me out through the narrows before turning into the small harbour of Quidi Vidi. Jim followed me out in a fishing boat with a film crew and then turned back for St. Johns harbour, leaving me to paddle through the night. There were a few long liners heading for St. Johns but nothing else. It was a clear night and after three years of planning I was finally on my way and enjoying it. I felt good.

My speed while paddling was 3 knots, as registered by the GPS. I was very pleased with that. In the morning, out of sight from the land, I was well and truly on my own. I had covered about 40 miles-a good night’s paddle-and it was time to get some sleep. Once I had changed my clothes and was in my sleeping bag, it did not take long to fall sleep, but I managed only a couple of hours. Waking up, I looked out the small porthole to see rain pouring down, and decided to go back to sleep. About 12 noon, I woke again and decided to call Jim and let him know everything was going well. I moved some bags and noticed water in the cabin and wondered where it had come from! I opened the air vent in the door and put my hand through to feel for any water in the cockpit. There was water over three-quarters of the way up the door. This was a serious problem. A bilge pump system was installed through all the compartments to the cabin, for just such a scenario. Using this, I started to pump the water out of the cockpit via the cabin. Realising I was making no progress, I had to get into the cockpit and use the hand pump. I decided to take my watch off, because I would be immersed in the water and although it was water-resistant, it was not waterproof.

While I was in the cockpit pumping the water out, the sea became rough enough to tip me overboard. A re-entry procedure involved my having to pull myself up by reaching over the side of the cockpit and hauling myself in. This happened twice. The sea was now coming in faster than I could pump it out. I had to make a decision that I was not happy with, but there was nothing else I could do. I got into my life raft, after activating the canister to inflate it. Because of the rough sea conditions, the life raft was thrown against the kayak, ripping a hole in the bottom. I spent the next 32 hours in sea temperatures of 3 degrees C above zero, pumping water out of the raft every few minutes. I survived the ordeal by planning next year’s trip. A Newfoundland Coast Guard ship, the Cowley, eventually picked me up.

Before I left the kayak, I attached a 30-inch sea anchor/drogue made of nylon onto her, yet when she was picked up later by the Cowley, she had a 12-inch silk drogue on. This led us to believe that the kayak was found by a vessel that claimed salvage and stripped her of all our equipment. There was no other explanation for the loss of my kit.

It took over four months for me to regain feeling in my feet and to learn to walk again. At the same time I had to find another builder and get all the equipment together. Kirton Kayak of Crediton in Devon built the new boat with the help of a yacht designer. She was made with the state-of-the-art materials that made her lighter but tougher. We used the same hull mould but changed everything inside (including the layout of the cabin). There was an electric pump alongside foot and hand pumps. A yacht hatch was used for the door.

Most of the equipment sponsors stayed on board and some even insisted, “You must try again,” before I told them that I was planning to. The foot-and-mouth epidemic put me out of work as an outdoor pursuits instructor; therefore, I had more time to help with the construction and did some of it myself.We were able to use Nigel Dennis’ kayaking centre in North Wales as a base, to enable us to carry out sea trials with help from the RNLI (Royal National Lifeboat Institute).

Our main sponsor had pulled out and even though we had a company filming footage of the challenge, from the building of the kayak to the trials, we could not get another main sponsor. We managed to get on TV, into the papers, and on the radio, but still nobody was interested. I had to make a decision; wait until we got a main sponsor (some of the equipment sponsors could not wait), or go forward with the expedition and hope for the best. Without a financial sponsor I had to borrow the money, knowing the only way to pay it back (if still no sponsor came on board) was to sell my house. I am a doer and not a talker, so I decided the first week in June to send the crated kayak to Newfoundland, regardless of the financial situation.

Jim and I followed a week later, hanging on as long as possible in an attempt to secure some kind of sponsorship deal, but to no avail. A few days after arriving in Newfoundland, CBC contacted us for an interview. To our disappointment, the interview that was broadcast reflected the rescue of last year, not on the forthcoming challenge. They wanted to make an issue about who would pay for the recovery if there was another failure.

The Canadian Coastguard was once again very helpful and gave us up-to-date weatherforecasts. Jim and I would visit them twice a day when the reports came in. On the morning of June 22, the forecast was good: gentle westerly winds with calm seas. I decided to leave at 20:00 on the ebb tide. On leaving St. Johns the weather was ideal-flat seas and no wind. My sequence of targets for the challenge was to survive the first 24 hours (because of the events of last year), cross the Newfoundland waters, reach the quarter mark, reach the halfway mark, enter English waters and land in southern Ireland.

Two days out, the sea state started to worsen. The rough seas prevented me from cooking, and for the rest of the journey I ate all my meals cold. The Coast Guard informed Jim that I was experiencing October weather in June; it was the worst weather they had on record. In one night, Mother Nature forced me backwards-60 miles to the north. A couple of weeks into the journey, I encountered several problems, starting with a snapped rudder cable, which caused difficulty steering. Because of the size of the boat, a rudder was necessary to control the boat. To repair the cable, I tied paracord from the cable to the steering plate.

A couple of days later, the steering plate broke. The only way to repair this was to cut a strap from my lifejacket to make a stirrup-like fitting, as I had no means of riveting the plate back together. Shortly after completing the repair, as I was just about to start paddling, I heard a knocking sound. On investigating, I discovered the shackle from the sea anchor had disappeared. In order to repair this problem, I had to brave the elements and swim to the back of the boat. The sea state was about Force five. Not wanting to lose another shackle while undertaking the repair in such rough conditions, I decided to use another length of paracord. On getting back into the kayak I cut my hand and my blood washed off in the sea. Not long after this a shark appeared! After changing my underpants, I decided that if I kept paddling, it might think I was a machine and not an edible delight. To my amazement, this seemed to work and the shark soon swam off.

During this time I had not seen the sun once; therefore, my solar panels were not performing as well as they should have been. Everything electrical had to be switched off so that the tracking device would not fail. My desalinator demanded too much power, so I had to start rationing my water.

One hundred miles from the halfway point, after a good days’ paddle, I undressed (as I did after every paddle) in preparation for getting into the cabin. I lifted the hatch to find that the right hinge had broken. This had been the only imaginable scenario that would have the dire consequence of putting an end to the expedition!

I could not believe my luck; yet again my crossing was to fail due to a ‘technical’ problem. All I could do was to scream out and cry. My mind swam with thoughts of my hard effort of four years of planning, my expenditures, and the media having a ‘field day’ at my expense. They were waiting for any hint of failure to justify their negative attitude at the start.

I contacted Jim by satellite phone. I could not get hold of him, so I left a message on his answer machine telling him that it was all over. I called Jim back later about five minutes after I had calmed down, and suggested a possible solution: call for aid from a ship to help me replace the hatch. Jim told me he needed a couple of hours to try to sort something out. In the meantime, I was to get in the cabin and secure the hatch as best I could to prevent the sea from coming in. Calling Jim back, as he was unable to call me, he informed me there would be an engineer from the design firm on stand-by in the morning and to recall what equipment I had onboard for a possible repair. He also suggested we pray for calm seas.

In the morning, the sea was flat and deadly quiet. On contacting Jim he gave me a number to call the engineer, Mark. The first thing Mark asked was what tools I had on board, to which I replied, “A junior hacksaw, a knife and screwdrivers.” Our first problem negotiating the repair was that Mark spoke in metric terms and I was used to imperial measurements. First I had to find a tube measuring approximately one quarter of an inch in diameter by one and a half inches long, that I could cut into a hinge shape. The only thing that would fit this description was the soft metal casing on my file. Not having a vice or any engineering equipment, I had to use my knees to hold the tube as I cut away sections with my junior hacksaw. Imagine trying to saw while lying on your back in an enclosed space with your knees bent, acting like a vice, and holding the phone on your shoulder to receive instruction.

Having heard me swear rather loudly, Mark asked what the problem was and I informed him that I had cut through my knee! Mark asked me if I was ok. “It’s only blood!” I replied. A few moments later, I swore again. Mark asked, “What’s wrong now?” I told him that I had cut my other knee! Hearing me swear yet again, Mark asked, “What’s the matter now? You’ve only got two knees.” I said, “I know-this time I’ve cut my finger!”

During the call with Mark, I told him that there was a major design fault with the hatch and that it was absolutely useless, and perhaps he should inform the management what rubbish it was. (After the crossing, when I was back in England, Mark phoned to ask how things were. It was then I found out he was actually the boss, and they had developed a new hinge!)

After cutting the tube, I had to cut through a bolt which took some time. I had to cut it precisely, so that it protruded through the end of the tube. Once this was done, they had to be joined together. Without a welding kit, all I had on hand to join them was the sticky tape wrapped around my food. The hinge was protected by a plastic cover, which was held in place with some tape. This whole operation took over five hours! For the next four days I endured yet another storm and was stuck in my cabin the whole time. Thankfully, the hinge worked and, after the initial failure, it went on to survive the duration of the challenge.

The sea was undulating with 20- to 25-foot swells, visibility was down to approximately 100 yards and it was very quiet. The only noise was from the ‘splash’, ‘splash’ of my blades going into the water, and then suddenly there was a ‘splosh.’ I was puzzled as to where this other sound was coming from. After about five minutes I managed to angle the kayak in such a way that I could see behind me. Lo and behold there was a huge dorsal fin! As I looked to the left of my cockpit I saw the head of a killer whale directly below me. My initial reaction was to paddle to the right to get away and to shake it off. Believe it or not, the whale followed me. So I then paddled to the left-it stayed with me. I then paddled in a circle but it still stayed with me. After what seemed like a long time, I stopped paddling and shouted, “Get lost!” and to my amazement, it did!

The consequences of being upended by a whale would be disastrous, because it could severely damage the boat.

The Canadian Coast Guard informed me (through Jim) that I was too far north. For a very long time now, the current was keeping me going northwards as opposed to south. This was making me very anxious because I was in an Icelandic current and not the Gulf Stream, which is where I had hoped to be. If I continued to drift north, I was afraid I would miss Ireland altogether and be heading towards more treacherous waters. Luckily the winds changed to north-westerlies, which helped to steer me back on course.

Jim informed me that he was going to Ireland to find a number of uitable options for potential landing spots during the last two weeks of my ‘expected’ arrival. One of them was Killybegs.

While he was there, he warned me that the fishing fleet was outward bound and to be careful over the next few days.

Two hundred miles from Ireland, paddling in a Force five or six, I sighted my first ship after many weeks of no human contact. As I paddled towards it, I saw that it was the deep-sea fishing boat Mendoza. As I neared the vessel, I saw the captain come out of the bridge with his binoculars. Judging by his reaction, he could not believe what he saw; he dragged his first mate out to witness and confirm that he wasn’t going mad. I approached and paddled around the boat. Seeing the crew hauling in the catch, I shouted, “Good morning!” Their faces were a picture and they kept looking at each other, pointing at me in total disbelief.

From the time I repaired the broken hatch, I was unable to vent the cabin. Condensation had built up considerably. Over the following weeks the electronics become troublesome due to the moisture. Four days away from the finish, the main phone ceased to function. The only option open to me was to use the emergency mobile phone, which, due to the limited power source, provided just two days of communication with the outside world. If this wasn’t bad enough, the tracking device also started to act up. While in contact with Jim, he informed me ‘Stratos’ was having trouble locating me via the tracking system. Unfortunately, the communication and tracking devices were not designed to withstand such battering in a small craft like a kayak. The fact that they had worked so well for so long under such adverse conditions is a credit to the company that manufactured and fitted them. Forty-eight hours away from landing, the condensation situation worsened. Consequently the whole system shut down. In spite of all these problems, I was not fazed as I knew it was only a matter of days before I reached land.

09:12 hours on September 4, I spotted land to the south! I paddled east and the wind pushed me towards the land.

From analysing the surrounding land features, I knew I was in Donegal Bay. During that night as I mopped out the cabin with a chamois cloth, I spotted three lights on the horizon. I soon realised what they were, and quickly got undressed from my one-pieced fleece suit and lunged into the cockpit, naked-I had no time to get into my paddling gear!-as a fishing trawler missed me by a mere 100 feet! At dawn there was a thick sea mist encroaching, but around lunchtime the mist cleared to reveal the cliffs of southern Ireland. There was no way I could spend another night sleeping at sea with the cliffs so close-I was determined to paddle as far as I could and then land. About 17:00 hours I saw a small fishing boat and asked where the nearest harbour was. They directed me and I headed towards the small fishing village of Beldereg, County Mayo.

Upon entering the harbour, I spotted two gentlemen and shouted to them. At the same time a Coast Guard helicopter flew overhead. I had been forewarned that a helicopter might come looking for me. I tied the kayak up to the harbour wall and climbed up the ladder. The two gentlemen offered to help but I flatly refused, explaining that I had to walk on my own first. As I took my first step, I fell over onto my knees. The gentlemen asked, “Can we help you now?” “Yes, please do,” I replied. When I asked, “Where am I?” they looked confused. I explained that I had just paddled from St. Johns in Newfoundland and had been at sea for 76 days.

They helped me around to their cottage, approximately 300 yards away, where I was offered a cup of tea-my first hot substance in 74 days. While I was drinking the tea, the helicopter landed in a nearby field. Jim and the air crew jumped out and escorted me to the helicopter. The kayak was secured in the harbour on a trailer and covered over, and we collected it the following day. We flew to Killybegs-the place where my friends and family had been waiting for more than three days for my arrival.

The helicopter touched down on a football pitch in Killybegs where numerous friends, family, and the media gathered to meet me. After the initial greetings I was taken to the local hospital for a medical check up. The doctor was astounded by how fit and healthy I was, considering my ordeal. Most people were impressed that I was able to walk (if a bit wobbly at times), since I had been confined in a small area for a relatively long period of time and was unable to use my legs properly.

The aim of the challenge was two-fold. I wanted to raise awareness and hopefully £100,000 for two childrens’ hospice organizations, and to achieve the ‘Everest of kayaking.’ With the right boat, equipment, and mental attitude, I knew I could succeed in making a solo, unsupported crossing of the Atlantic. I felt that, due to the media’s attention on the failure of the first attempt, a golden opportunity to promote the sport of kayaking was overlooked and the challenge did not get the recognition that it truly deserved.

Afterword

I would like to thank everybody who helped ensure the success of the challenge. The childrens’ hospice charities are “Rainbow” in Leicester and “Ty Hafan” in Wales. Those who would like to donate money to these charities can send donations to the following address: 137, Brooks Lane, Whitwick, Leicestershire, LE67 5DZ. Further information can be obtained from the Web site: www.outdoorchallenge.co.uk/nakc2000

Sponsors

Mega, Lendal, Phoenix, Beauford, LandRover, Atlantic Containers, Royal National Lifeboat Institute, Keela, Kirton Kayaks, Stratos.

Welshman Peter Bray began paddling at the age of 12 and has competed in numerous endurance kayaking competitions. He served in British Army Special Forces and has been an outdoor skills instructor.

MSR Reactor

The pot has a folding handle and a clear plastic lid. The butane/propane cartridges and the burner head fit inside the pot. A small square of pack towel supplied with the stove keeps things from rattling around.

The stove and the pot are designed to work as a unit, and there’s nothing to support any other cookware over the burner, so you won’t be doing any sautÈing over it. But for the fast-and-light crowd, just boil up some water in the Reactor, simmer a dehydrated meal in a thermos and dinner is served.

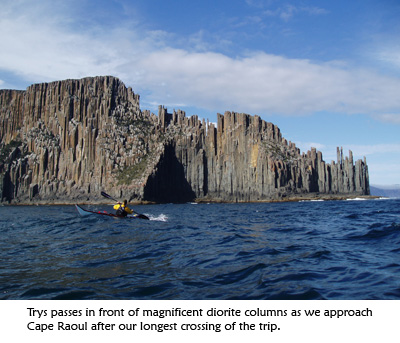

Rounding Tassie

Three Paddlers from the U.K. are the first women to take on the 900-mile circumnavigation of Tasmania.

We’re not going anywhere! This is pointless! Trys shouted into the wind. My heart sank—I didn’t want to stop. Ahead of us, tantalizingly close, lay a headland that would offer us some protection from the wind. If only we could reach it, we could go ashore and camp beneath the trees. Trys was right, though—we’d been paddling for two hours and had barely made a mile. The sea and wind were stinging our eyes as we battled, head-down, into the full force of a gale. Again.Trys, Gemma and I all desperately wanted to complete our circumnavigation of Tasmania in the six weeks we’d allocated, but day after day, we had faced strong headwinds. The demoralizing and energy-sapping weather meant that after the first two weeks of paddling, we were already behind schedule, and we needed to paddle whenever possible. We’d hoped to make up some time that morning when we left the North Coast town of Bridport. The wind had already been buffeting the trees, so we tried sticking close to shore to sneak along the coast for as long as possible. Unfortunately, the wind had picked up until it was stronger than we were.

“Can we just push it for a few more minutes and get to the beach ahead?” I hollered back.

The three of us were only a few yards apart, but the wind tore our words from our lips.

“We can try,” Trys bellowed, unconvinced but charitable. Gemma nodded agreement.

I tried to guess how far away the headland was. It must be only 400 yards ahead. Surely we could reach it. Five minutes passed. Ten minutes. My face was chapped from the sting of the wind. My kayak bounced and thudded down into the chop, but the headland wasn’t getting any closer.

“This IS pointless!” Gemma shouted.

My shoulders and head dropped with frustration, and I knew she was right. Reluctantly, I pointed my kayak toward the beach to our left, hoping we could land there. Unfortunately, the choice that lay in that direction wasn’t great. Four hundred yards of shallows separated us from high ground. It would be exhausting to haul our heavily laden kayaks there and back. The only real option was to turn back to Bridport. It would be gut-wrenching to retreat after two hours of intense effort, but I knew it was the most sensible choice. On a calm day, we could recover the progress we’d lost in 20 minutes, but I ached all the same. It felt so unfair that we could try so hard and fail. I choked back tears and wondered if the weather would ever allow us to make it around the island.

Where I live, in rural New England, if you ask old-timers for directions to a nearby town, they’re apt to tell you that “you can’t get there from here.” For North American paddlers flying commercial airlines to kayaking and camping trips, the issue is not whether you can get there, but whether your gear can. Things like fuel canisters and flares are pretty obvious no-fly items. But what about candles, seam sealer, insect repellent or bear repellent spray? The U.S. government and many commercial airlines prohibit flying with a growing number of standard kayak and camping gear items. Given increased restrictions and the potential of costly fines, what’s a paddler to do?

You Can Get There-but Can Your Gear? Flying with Kayaking and Camping Gear

Where I live, in rural New England, if you ask old-timers for directions to a nearby town, they’re apt to tell you that “you can’t get there from here.” For North American paddlers flying commercial airlines to kayaking and camping trips, the issue is not whether you can get there, but whether your gear can. Things like fuel canisters and flares are pretty obvious no-fly items. But what about candles, seam sealer, insect repellent or bear repellent spray? The U.S. government and many commercial airlines prohibit flying with a growing number of standard kayak and camping gear items. Given increased restrictions and the potential of costly fines, what’s a paddler to do?

Bright Lights 4 Compact, High-Intensity Flashlights

Expedition paddlers exploring unfamiliar coastlines are almost certain to get into a situation that requires paddling at night. Despite careful pre-trip planning and studying charts to look for possible landing and camping sites, unforeseen delays can require navigating in darkness. This can even happen on a simple day trip, so all paddlers should be prepared for paddling at night. Some type of bright white light is required safety equipment for alerting other boaters as well as for finding a hospitable landing. A powerful light is also especially useful for picking up reflective channel markers or the reflective tape on your partner’s PFD or kayak from a long distance.

I used to carry a powerful underwater light designed for scuba diving. This light was bulky and was powered by eight D-cell alkaline batteries. It was bright, though, and completely waterproof.

Unfortunately, it was too big to go anywhere on deck, and it was even an awkward fit in the cockpit. It was expensive to purchase and expensive to run with less than two hours of burn time on a fresh set of the best alkaline batteries. The size and weight of all those D-cells limited me to carrying only one or two spare sets.

When this light finally died, I went through an assortment of cheaper, less durable alternatives, but none of the more compact flashlights were powerful enough for scoping out a strange shoreline.

A variety of high-power flashlights are now available in compact sizes. They are powered by 123A 3-volt lithium batteries, the same type used for many cameras and other high-drain electronic devices. Some of these lights are only slightly bigger than the popular compact flashlights that use two AA 1.5-volt alkaline batteries, but they are far more powerful. I recently tested two of these that are powered by three 123A cells and another pair that use just two cells.

The three-cell lights are much more expensive and slightly larger than the two-cell lights but are powerful enough to replace the large bulky spotlights I used to use. The lithium batteries are only 1 inches long (compared to 2 inches for a AA battery), so even the three-cell lights are small enough to carry any time you go paddling. They provide a bright, broad beam of light that is useful to a kayaker looking along the shore for a place to land.

All of these lights use xenon lamps. Xenon is an inert gas that fills the lamp bulb to allow the filament to burn hotter and brighter without burning out. They all produce a clear, consistent beam without the usual varying rings of light typical of standard flashlight beams. To test the lights, I took them for a night paddle along a heavily wooded, swampy lakeshore.

SureFire M3 Millennium Combat Light

SureFire M3 Millennium Combat Light

The M3 Combat Light is the largest and by far the most expensive of the four flashlights I tested. At $252, it’s billed as a “heavy-duty tactical flashlight to meet the needs of demanding customers such as military special operations units, SWAT teams and other law enforcement professionals.” The case is anodized aircraft aluminum with a checkered grip especially designed for the Rogers/SureFire combat grip—a technique used by the aforementioned customers when engaging opponents in the dark with a handgun. Sea kayakers won’t need that particular design feature, but the no-compromise quality built into this rugged light makes it a good choice for the demands of an expedition.

Although not rated for underwater use, such as diving, SureFire claims that all its current lights are waterproof to about 33 feet. I left it under about three feet of water overnight and found no moisture had entered the case. The switch is built into the tailpiece—turning it full clockwise turns the light on—but the tailpiece also functions as a momentary push-button switch when partially rotated. Backing the tailpiece off by turning it counterclockwise disables the push-button feature so the light can’t be accidentally activated when packed.

The M3 comes with a 225-lumen lamp and a 125-lumen lamp. On a set of three batteries, the 225-lumen lamp provides only 20 minutes of run-time, and a 125-lumen lamp runs one hour. With the high-output lamp installed, the M3 is by far the most powerful of the four lights I tested.

This light provides a useful range of at least 200 feet, completely illuminating the dark woods of the lakeshore I paddled along from that distance. The beam it throws is perhaps not as broad as my old diving spotlight, but it is amazingly intense for such a small package. I even took it out for a drive on a deserted country road and found it bright enough to drive by, held out the window of the car with the headlights turned off. Reflective road signs were visible over a half a mile away.

At just over seven inches long and with a bezel diameter of 1.62 inches, the M3 may not fit in small PFD pockets, but it’s still compact enough to carry in a chart case or perhaps secured with a Velcro loop to your PFD. A lanyard is included with the light. With the high-power lamp, it will burn through 123A batteries in a hurry, but for such power that’s a reasonable trade-off. SureFire sells its own brand of lithium batteries in a case of 12 for $21. These batteries are so small and lightweight, a kayaker could carry several cases on a long -expedition.

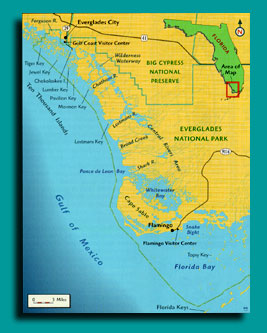

PADDLING THE SALTWATER FRINGE OF THE EVERGLADES

The sun was dropping fast as we hurriedly paddled our way among the low islands of mangrove trees. We were aiming for West Pass, a half mile distant. To our right, the Ferguson River flowed into Chokoloskee Bay behind a platoon of individual mangroves. I kept glancing back and forth between the nautical chart and the compass. It was imperative that we keep track of our position on the nautical chart, as we were paddling in Florida’s Ten Thousand Islands, a literal maze of mangrove trees rooted to the shallow ocean floor. They range from a single tree rising from the sea to thousands of mangroves, forming islands like jigsaw-puzzles measuring hundreds of acres in size.

Ahead, I spotted swiftly flowing water between two mangrove islands: West Pass Channel. Bill, my paddling partner, entered the channel first, and I followed. The push of the incoming tide immediately slowed us down. Moments later, we emerged into the Gulf of Mexico. The sun shone in a freshly washed cobalt-blue sky over two-foot waves that stretched westward as far as the eye could see.

Earlier in the day, a powerful thunderstorm had rumbled through just as we had arrived at the Gulf Coast Ranger Station, near Everglades City. The storm had delayed our departure by two hours and forced us to paddle rapidly to make it to our destination by nightfall. Three hours into the paddle, as we skirted the shallow northern shoreline of Tiger Key, we raised the rudders on the sea kayaks to prevent scraping the sandy bottom. One last turn around a narrow peninsula led onto Tiger Key beach.

Sea grape trees, lit red by the dying sun, hunched over the upper end of the sloped beach.

These generally low-slung coastal trees have large, round, shiny leaves that are leathery, to tolerate the strong sun. They produce a grape-like fruit in the fall, which settlers of a century ago gathered and made into jelly. I sat for a few moments in my kayak, relaxing my arms, and enjoying the cessation of repetitive motion. Moments later, the sun dropped below the horizon. We’d completed the seven-mile West Pass Route before dark.

I was on the tail end of a scouting expedition for a paddling guidebook I was writing. I had already spent most of the winter paddling the Everglades, and had been adventuring down here for a decade. My friend and fellow Tennessean, Bill “Worldwide” Armstrong, had flown down from our hometown of Knoxville to join me for the trip. *The beach of Tiger Key is one of 52 designated backcountry campsites within the confines of Everglades National Park. It lies at the extreme northern end of the preserve, where the fresh water of the mainland flows through sawgrass into innumerable channels, which in turn gather in rich estuaries to form rivers leading to the Gulf and thousands of outer islands. Most of the outer islands are very small, yet hundreds are five acres or more, like Tiger Key.

Our trip would take us through the Ten Thousand Islands area. We would be paddling 11 miles down the Gulf to Pavilion Key. The next day would be a short four miles to Mormon Key, allowing time for exploration and fishing. Then we would turn inland up the Chatham River and pass the old Watson Place, a pioneer homestead, before staying at Sweetwater Creek. We would then head north on the Wilderness Waterway seven miles to Sunday Bay, and finish our trip back at the Gulf Coast Ranger Station, for a total of 53 miles.

Loop possibilities in the Ten Thousand Islands are limited only by the paddler’s imagination, considering the numerous rivers, bay and creeks of the area. Sixteen backcountry campsites in the

vicinity, open to boaters of all stripes, make desirable routes all the more feasible. There are three types of backcountry campsites in Everglades National Park: beach campsites, ground campsites and chickees. Beach campsites are located along the Gulf of Mexico, either on the mainland or on islands.

These beaches are formed by the disintegration of millions upon millions of shells, pulverized over time by wave action, and deposited on the shores of the keys and coast. They have a yellowish-white tint, and are not as fine as the sands of the northern Gulf, where the sand is deposited from the Southern Appalachian Mountains, then bleached sugar white.

Ground campsites are primarily located inland. They are situated on discarded mounds of shells, remnants of numerous generations of Calusa Indians who roamed the Everglades since pre-Columbian days. The Calusa wandered Florida from Lake Okeechobee south to Cape Sable, the southwestern tip of the Florida mainland. They paddled long canoes made from hollowed-out cypress logs to collect food from the abundance of saltwater, freshwater and land sources. The shell mounds they created provided a place to camp where there was no land, and they still serve this purpose today.

The third type of campsite, chickees, are built in areas where there is no dry land. These are elevated platforms on stilts with open sides and a sloped metal roof. Vault toilets are attached to the platform by a gangway. Chickees are named after Calusa thatch huts of similar design that they constructed on terra firma. In their day, the Calusa would keep a smoldering fire of black mangrove going in the chickees to keep out the mosquitoes, and they slept on a raised platform beneath the thatch to catch the breezes.

Many first-time Everglades paddlers are surprised at what really comprises the Everglades. There are two preconceived notions of the Everglades: The first image is of the Everglades as jungle, with tall trees filled with exotic birds, and snakes dangle from limbs hanging over alligator-filled waters. This image actually comes close to describing the Big Cypress Swamp, which lies directly north of the Everglades.

The second image, the Everglades as a sea of water and grass shimmering to the horizon, with the sun mercilessly beating down, is partly accurate, but describes none of this park’s paddling area. There are numerous other ecosystems here, such as pine islands where deer thrive and panthers may roam, or tropical hardwood hammocks where trees like the strangler fig lend a lush, tropical Southern Florida look. Cypress sloughs and coastal prairies are other ecosystems found here. For the paddler, there are two primary ecosystems: coastal mangrove swamps and the Gulf of Mexico, also known as the “outside.” Of these, the mangrove swamp dominates the paddling area. With the perpetual mixing of fresh and salt waters, mangrove trees thrive here, forming the largest, thickest, tallest mangrove forest on the face of the planet. Mangroves exceed 100 feet in height along the Shark River. Extending more than 90 miles from north to south and 50 miles west to east, Everglades National Park (ENP) is the largest nature preserve east of the Mississippi; in the lower 48 states, it’s second in size only to Death Valley National Park. The paddling area of ENP stretches 90 miles along the Gulf and 20 or so miles inland. There are more than 400 miles of commonly paddled routes within the ENP. All of these routes connect the two primary launch points, Flamingo and Everglades City, with backcountry campsites.

From Flamingo, paddlers can explore the keys of Florida Bay, the aptly named Whitewater Bay, Cape Sable and the southern, interior rivers. The Central Rivers Area is at least a day’s paddle away from Flamingo. From Everglades City in the north, paddlers can explore the Ten Thousand Islands, the northern Gulf and the interior bays and creeks of the north end. The Central Rivers Area is at least a day’s paddle away to the south.

The Marjory Stoneman Douglas Wilderness covers about 80 percent of the total ENP. In 1947, Douglas wrote Everglades: Sea of Grass, which was instrumental in informing the public about the uniqueness of the Everglades. Douglas’ book launched the move to establish the Everglades as a national park. *Unfortunately, when designating the ENP as a Wilderness Area in 1978, the water portions of the park were exempted from the “no motorized vehicles” rule of the Wilderness Act. This means that powerboats are allowed in the wilderness, in most of the paddling areas of the Everglades. I have not found this to be a distraction, since the scenery and overall experience simply overwhelm a few boats whizzing by. The farther you get from Everglades City or Flamingo, the fewer boats you will see.

Navigating can be challenging in this seemingly endless profusion of bays, ponds, creeks, inlets, lakes, rivers, undulating shorelines and keys. The horizon is unbroken by elevated features, such as mountain peaks or river valleys, and mangroves form a green coast that can appear to be the same at different locations. Add distance to the mix, and groups of mangrove islands look like a contiguous shoreline. Coastal configurations lose their curves. Water, cloud and sky merge into distorted mirages. The horizon is lost: Boats appear to float in the air, birds seemingly fly underwater, and islands seem to shift imperceptibly. Now, throw in tidal variation.

When the tide is out, what should be a separate group of keys, according to a nautical chart, is connected by land. (The Everglades are shallow, averaging two to four feet, often less, and rarely deeper than six feet, with the exception of major tidal rivers.) *Channels, and the Wilderness Waterway-a 100-mile route that runs the north-south length of the park-are well marked by beacons. In some places, like Chokoloskee Pass, it is a matter of simply following the channel markers and boat traffic. In other places, like Hells Half Acre, tarot cards and a rabbit’s foot are needed in addition to a GPS, nautical charts, USGS quadrangle maps and a compass. Paddlers often start out on a marked trail, then branch off to unmarked routes. Overall, however, there are enough fixed positions such as campsites, channel markers and other signs to periodically confirm your position, without so many markers that the backcountry becomes a sign-posted highway in the watery wilderness.

When the tide is out, what should be a separate group of keys, according to a nautical chart, is connected by land. (The Everglades are shallow, averaging two to four feet, often less, and rarely deeper than six feet, with the exception of major tidal rivers.) *Channels, and the Wilderness Waterway-a 100-mile route that runs the north-south length of the park-are well marked by beacons. In some places, like Chokoloskee Pass, it is a matter of simply following the channel markers and boat traffic. In other places, like Hells Half Acre, tarot cards and a rabbit’s foot are needed in addition to a GPS, nautical charts, USGS quadrangle maps and a compass. Paddlers often start out on a marked trail, then branch off to unmarked routes. Overall, however, there are enough fixed positions such as campsites, channel markers and other signs to periodically confirm your position, without so many markers that the backcountry becomes a sign-posted highway in the watery wilderness.

Some of the biggest problems here are unseen and little. The unseen problem is wind. With great expanses of wide-open park waters, wind can be a problem. It is often windy: 1025 knots, on average. Small craft advisories are common in the Gulf. Paddlers often strike out early in the morning to avoid these winds, which generally kick up in the afternoon and die down around dusk.

These breezes can be your ally, as they clear insects-mosquitoes and no-see-ums (the little problems). The Calusa used a combination of fish oil and pine tar smeared on their bodies to keep the “swamp angels” at bay. Modern Everglades explorers should be prepared with insect repellent (both cream and spray), long pants and shirts, and a head net. In winter, the bugs can range from nonexistent to maddening. During summer, the bugs are so thick that they keep the backcountry essentially deserted. (Don’t come to the Everglades in summer!) There are few bug problems on the water, except occasionally along very narrow creeks.

December through March in South Florida is dry and pleasant, with highs averaging in the 70s and lows in the upper 50s. Precipitation runs under two inches per month. Be prepared for sunny conditions year-round with wide hats, sunglasses and sunscreen. Everglades paddlers must carry all their drinking water with them. A gallon per person per day is recommended.

Arriving at Tiger Key, I erected the tent by the flickering flames of a driftwood fire, backlit by a rising moon. Bill grilled hamburgers as the tide drifted out, extending our beach. It was a good thing we landed

around high tide. With a full moon and corresponding extreme tides, paddlers often have to drag their boats a long way to access the water. The ranger stations give out free tide charts that are very helpful in planning paddle times.

Early the next morning, a few no-see-ums nagged us as we loaded the kayaks and headed south on calm waters along the Pavilion Key Route. The expanse of the Gulf lay to our right and the labyrinth of islands to our left. As we paddled southeast along the edge of the keys, we decided to try our luck at trolling. I rigged my medium-weight rod with a Mirrolure, a minnow-like artificial lure, and fastened the rod under the deck bungies. It wasn’t long before the pole jerked, and I reeled in a two-pound sea trout-numerous in the Gulf.

When trolling, use lures that float. That way, if you have to stop, the lure won’t snag on the ocean bottom. Fishing is popular in the Everglades. In addition to fishing from a boat, I’ve had good luck surf fishing for snook, especially when I’ve used a Mirrolure on a rising tide. Snook, Jack Crevalle and mangrove snapper roam the rich, brackish waters that lie between the salty Gulf and the inland sheet of freshwater flowing toward the ocean. Sea trout and reds are common along the coast. Of course, angling areas often overlap. A valid Florida saltwater license is required. When obtaining your license, check the current size and creel limits.

Birding is a deservedly popular pastime here. Avian numbers aren’t nearly what they were when plume hunters depleted and threatened the bird population in the late 1800s. Subsequently, the Audubon Society established rangers in the ‘Glades to protect the birds, at the Society’s own expense. When a ranger was killed by plume hunters in 1907, a national outcry ensued, ultimately increasing protection for Southern Florida birds. Today, avian enthusiasts still have plenty to see, from roseate spoonbills-often mistaken for pink flamingos-to pelicans, eagles and osprey. If you wish to do birding here, be sure to bring binoculars and a field guide.

We stopped for lunch at Jewel Key, one of just a few islands with a rocky beach. A “rocky” beach here is defined as a few rocks mixed in with a lot of sand. Most beaches are sand beaches. While the beaches are kind to kayaks, underneath the water lies a different menace: oyster bars. These large clumps of shells with sharp edges will scrape a plastic kayak or glass boat and turn a folding kayak into a shredded boat. I do not recommend a folding kayak for the northern Everglades. Oyster bars are often found in island shallows. When walking here, wear shoes that cover your entire foot. Paddlers in the southern Flamingo area of the ‘Glades don’t face much of this hazard.

Beyond Jewel Key, we kept southeast. The turquoise waters of the open Gulf lay to our right, while a labyrinth of verdant islands shielded the mainland. The sun shone brightly overhead. Rabbit Key, a small island of a few acres, was our next stopping point. A couple of hours later, three miles from Jewel Key, we were paddling along the eastern shoreline of Rabbit Key. Paddling around a point of land, we turned and followed a narrow trail of water inland. It opened out into a broad, sandy lagoon-a protected backcountry campsite. Rabbit Key is within striking distance of Chokoloskee Island, the other jumping-off point for the Ten Thousand Islands. We stretched our legs, then returned to the boats, as the afternoon was passing quickly.

We then veered due south into wide-open, but shallow waters. The ocean was as smooth as polished marble. We passed Little Pavilion Key, just a smattering of sandbars. A century ago clammers lived here in huts perched on stilts over the water. These settlers harvested clams from the adjacent waters, finding them with their feet (which were wrapped in canvas to keep them from getting cut, yet allowing them to feel the clams). Storms, winds and the tides have obliterated any evidence of their time here. A short time later, we began the approach to Pavilion Key. With the tide out, we had to stroke far into the Gulf to access the island, in order to avoid extremely shallow water.

Pavilion Key is more than a mile long and a quarter-mile wide. The backcountry camping area, on the sandy northern tip of the isle, accommodates 20 campers per night. A long spit of land extends out from the forested part of Pavilion Key, catching ocean breezes. The long western shore is mostly sand, offering beachcombing opportunities.

Cool air blew in from the ocean as Bill and I settled down by the campfire and ate shish kebabs while we reflected on our 11-mile day. To the west, the sun descended into the Gulf of Mexico, painting the sky multiple hues, from yellow to orange to pink, then begrudgingly giving way to a slaty dusk smudged with high clouds. Within an hour, the moon was so bright we could explore the beach without flashlights. Then we heard a rustling by the boats.

Small dark shapes scurrying along the sand contrasted with the lighter beach. Raccoons! We raced after them, and they disappeared into the trees. They couldn’t get our food, however, since we had stored all of our food and water inside the hatched compartments of the kayaks. Pavilion Key and most other beaches have food-habituated raccoons that will get your food and tap into your water supply. Store your food and water inside your kayaks, as the masked marauders have been known to cut into each and every jug of agua, effectively ending a trip.

A continuous popping of the tent fly awoke me the next morning: wind-strong wind. A front had blown in on us sometime in the night. After a cup of hot coffee and a quick walk on the beach, the two of us paddled into the early morning sun with a brisk wind at our backs. We skirted Dog Key, then entered wide-open rolling water from Pavilion Key to Mormon Key. This area of the coastline turns from southeast to south. The big turn is known as Chatham Bend. More mishaps have occurred in the four-mile stretch between Mormon Key and Pavilion Key than in any other waters in the Park, according to park rangers. Most Gulf incidents have occurred when canoeists have tried to paddle the open Gulf during smallcraft advisories. They paddle out to Pavilion Key, where they get trapped by high winds. When they make an ill-fated break for the coast, they end up getting swamped.

Sea kayakers fare far better in the Gulf. Current paddler use in the Park is split roughly in half between canoeists and sea kayakers, but the rise in sea kayaking over the past decade has been phenomenal. A decade ago, less than ten percent of backcountry visits were by kayak. Sit-on-top kayaks have increased in popularity in the last few years, as well. However, it can be cold in the ‘Glades, and I would rather be inside a boat when a cold front blows in from the north, kicking up winds and dropping temperatures into the fifties and below.

We cut through the murky waves, and safely made Mormon Key. Gulf waters are normally clear over a mud and/or sand bottom, but excessive winds can turn the Gulf into chocolate milk. In Florida Bay, in the southern Everglades, the clear azure waters are much like those of Key West and the lower keys. In the interior ‘Glades, away from the Gulf, the water is clear, with a few exceptions like often-murky Broad Creek.

It was very windy as we set up camp, so we were grounded for the time. I set out to explore the key while Bill rested beneath a tarp, nursing a sore back. As I walked along the sand beach to the south, I watched the waves beat the shoreline. A scattering of broken conch shells in pastel tones of ivory and pink lay at the high-tide line. These were remnants of the Calusa: They discarded the conch shells after harvesting the delicate morsels inside. Farther around the island, broken slabs of concrete extended away from the island: remains of a dock that belonged to a settler who lived here with both his first and second wives in the early 1900s. Locals then dubbed the island “Mormon Key.” The Everglades are loaded with other interesting names that lead one to ponder their origin, including Jack Daniels Key, Demijohn Key, Gun Rock Point, Topsy Key, Lostmans Five, Snake Bight, Darwins Place and many more.

We arose the next morning to gentle waves lapping at the beach and a slanting sun promising a warm day. I started the coffee and Bill began breaking camp. We quickly loaded the boats to take advantage of the smooth water. The placid ocean made for easy paddling as we left the Gulf on the Chatham River Route and headed to the “inside,” up the Chatham River. The tide was in our favor, and after three miles of paddling, we found ourselves at Watson’s Place campsite. Watson’s Place is a 35-acre shell mound that was once the farm of the notorious Ed Watson. He had the nasty habit of hiring workers for his sugar cane, banana and vegetable farm and killing them after they had worked for him, rather than paying them. Word of Watson’s deeds spread among the locals and, in 1910, upon landing at Chokoloskee Island, Watson was gunned down by a posse. Most of Watson’s victims were never found. It is rumored that the ghosts of the slain roam the homesite.

We pulled up to the wooden campsite dock and tied up the boats. A large black kettle circled by bricks and a low, square cistern lay to the left of the dock. Everglades settlers obtained fresh water by collecting roof runoff, then running pipes to cisterns for storage. The kettle was once used to boil sugar cane “juice” into syrup. Tall gumbo-limbo trees that once shaded the homestead backed the clearing. Gumbo-limbo trees are sometimes called the “tourist tree,” since they have a distinctive peeling red bark under a spreading leaf crown.

After stretching our legs at this unfortunate site, we climbed back into the kayaks and continued up the Chatham River. A short time later, we intersected the Wilderness Waterway. The mangrove-lined river is around 100 feet wide here, in contrast with the open Gulf. While strong tides can effectively block passage around the mouths of rivers at the Gulf, the effect is more moderate farther inland. Here, seven miles inland, while the tide had turned against us, there was minimal tidal influence. The shadows and rich colors of the dense green foliage indicated that it was late afternoon.

We stopped paddling to take a look at the nautical chart. Comparing the chart to the shape of the low mangrove shoreline around us, we found the slender mouth of Sweetwater Creek. The stream was tranquil in comparison to the raucous waves of the Gulf the day before. As its name implies, tasty fresh water flows out of the ‘Glades in the upper reaches of this creek. Only a few birds broke the wilderness silence while we paddled up Sweetwater Creek. The lush foliage closed in until the stream was only 40 feet wide. It felt as though we were very far off the beaten path.

Two miles from the Wilderness Waterway, after a half hour of paddling, we arrived at the Sweetwater chickee. This was a “double” chickee, with two camping platforms attached by a central gangway and a vault toilet. A couple of fellow paddlers had already set up their tent on one side of the chickee. After setting up camp, we exchanged paddling tales with our neighbors. They had flown down from New York and were paddling folding kayaks. I warned them to be careful of the oyster beds they were sure to encounter in the Gulf.

The still air allowed the temperature to fall into the mid-fifties overnight. The dew was heavy on our boats the next morning, and my tent was so wet that it looked like there had been a rainstorm during the night, but there hadn’t been: Heavy dew is common in the Everglades. After we had breakfast and packed up the boats, Bill and I left the Sweetwater chickee and backtracked down the creek to return to the Wilderness Waterway. The morning sun was at our backs as we paddled northwest on the Last Huston Bay Route. Park service signs made our course fairly easy to follow, as we paddled past a series of shallow bays. Dense mangroves lined the bays, many of which were bisected by small creeks. While tidal influence is minimal here, some of these bays are large, and can kick up some big waves of their own.

By mid-afternoon we had paddled nine miles, and arrived at the Sunday Bay chickee, another double chickee. After setting up camp, I explored the creeks northeast of Sunday Bay while Bill fished. Returning to camp, I found that Bill had caught and released a couple of Jack Crevalle, known more for their fighting prowess than their edibility. Later, as we relaxed after dinner, a gentle night breeze tapped the boats against the chickee. I thought about those who live in northern states, facing the ravages of winter, while I lounged in shorts.

Arising at dawn, we put the boats in the water, climbed in, and shoved off. It was the last day of our trip. At the west end of Sunday Bay, we paddled out of the Wilderness Waterway, then headed west on the Hurddles Creek Route through the ultra-shallow Cross Bays. Within an hour, Bill and I came to Hurddles Creek, a small creek that was bordered by extremely thick stands of mangrove. A short time later, the creek opened into Mud Bay, which was less than a foot deep in many places. The last mile of Hurddles Creek went quickly, then we arrived at the Turner River.

This river is named for the guide who, in 1857, led the U.S. Army up the river as they attempted to drive Seminole Indians from the Everglades, in an effort to drive them out of Florida. The army paddled up the Turner, then marched through the interior swamps to destroy some Seminole villages. When the expedition’s leader was killed in an ambush, it brought an end to the Third Seminole War. The remaining Seminoles formed the nucleus of the Southern Florida tribes currently located on reservations in the Everglades.

As we paddled downstream, we passed a nearly vertical Calusa shell mound that reached 19 feet in height-lofty, by Everglades standards. I tried to imagine the generations of families gathering and consuming the shellfish to make such an enormous mound. Bill led the way into Chokoloskee Bay, and we paddled the final three miles on the Causeway Route. The busy bay made for a fitting reintegration into the “real” world. The past five days were packed with memories, from dolphins to the world’s best sunsets, to delicious, fresh-caught sea trout, to the eeriness of Watson’s Place.

I still had miles to paddle before completing the book, however, I looked forward to slipping back into my kayak to create more memories, for, as Marjory Stoneman Douglas put it in the opening sentence of her book, “There are no other Everglades in the world.” And there is no other experience in the world like paddling the Everglades.

ALIEN INVASION: COMING TO A BAY NEAR YOU

No, it’s not the latest summer blockbuster. The sacred haunts of the kayaker are being invaded. This is not the familiar invasion of fellow paddlers (a mixed blessing), but a new and more insidious invasion by other species altogether.

Cruise along the northern Mediterranean coast, and you will find that the shallow sea-grass beds that once teemed with life are now a desert of “killer” green algae, devoid of fish and invertebrates. From British Columbia to California, tranquil estuaries that echoed with flocks of migrating birds are now overgrown with acres of new salt marsh, obscuring the shoreline from birds and boaters alike. Along the volcanic rocky shores of Hawai’i, a new barnacle has taken up residence; the coast of South Africa is being invaded by an aggressive intertidal mussel; New Zealand and Australia are unwilling hosts of new seaweeds. Almost everywhere we paddle, old species are being swapped for new.

But new is not necessarily better.

Aliens, exotics, introductions, invaders…they go by many names, but all of these species share the common trait that they are spreading to places they don’t belong. They not only affect kayakers, but snorkelers, scuba divers, fishers, clam diggers, and other boaters. They can carry parasites and diseases. (Some of them are parasites and diseases.) They can damage fisheries, tourism, boating, property values, and industry. They can damage native plants, birds, fish, and mammals and disrupt the very natural world we paddle out to enjoy. That’s the bad news. The good news is that kayakers in particular can help marshal the defenses against them.

Anything can be an alien: seaweeds…

Do you dream, perhaps, of a Mediterranean vacation, floating silently over the teeming life of warm, shallow sea grass beds, trolling slowly for your dinner? When you go, you may catch more seaweed than fish on your line. Along the northern coast of this inland sea, the “killer” green alga called Caulerpa taxifolia is rapidly taking over. Divers first noticed Caulerpa in a small patch outside the Monaco aquarium in 1984. Recognized as a tropical species commonly used in aquaria, no one thought it would survive the cool water temperatures of winter. But this seaweed menace proved more robust than expected, and spread quickly along the coast into France and Spain, and as far east as Turkey.

Today, Caulerpa’s feathery green fronds and snaking root systems cover over 3,000 hectares (7,000 acres) of shallow seabed. And cover they do: rocks, sand, mud, seagrass beds; nothing is safe from its encroachment. Although Caulerpa is not toxic to humans, fish and sea urchins avoid it and seek more familiar ground-no easy task, when Caulerpa covers up to 100% of the ground, down to a depth of 35 m (114′). So much for catching dinner.

…plants…

Perhaps you are eschewing a sun-drenched holiday to explore the misty rainforest estuaries of the Pacific Northwest? Beware the invading smooth cordgrass, Spartina alterniflora. A beloved native of the east coast’s signature salt marshes, this grass is now a scourge of west-coast estuaries, where its characteristic circular patches expand across the tidal flat and displace native mud-dwellers.

Smooth cordgrass in the Pacific was first discovered in Willapa Bay, Washington, in the late 1800s. Its precise origin remains a mystery, but it was probably introduced accidentally, mixed in either with oyster shipments or with the rock and dirt ballast of wooden sailing ships. Spartina was later planted in other Northwest bays to control erosion and create duck (and duck-hunter) habitat.

Simply by growing along the water’s edge, smooth cordgrass drastically alters the shoreline. Its tall, stiff stems and long green leaves slow the flow of water, causing sediments to build up so high that the growing marsh is raised above the tideline. The semi-terrestrial meadow is no longer a suitable habitat for certain intertidal clams, for clam diggers (there goes dinner, again), or for the thousands of migratory and resident birds that depend on these estuaries for food. Boat access is affected too: with the ocean now farther away, you can no longer simply slide into your kayak from your backyard.

Invasive tendencies seem to run in the family: a second species of Atlantic cordgrass is also invading the Pacific, a South American cordgrass is invading North America, and worst of all, an English cordgrass planted widely in Europe, China, and Tasmania, is spreading rapidly around the world.

…animals…

Headed instead for the languid, coffee-colored waters of the Mississippi bayou? Keep your eyes open for nutria (Myocastor coypus), an overgrown swamp rat that may appear on the riverbank or even on a restaurant menu. These 20-pound nocturnal rodents were introduced from their native South America to the Gulf coast and southeastern states in the 1930s and ’40s for their fur, and at one time a breeding pair fetched up to $2,500 US.

Unfortunately, the demand for nutria fur can’t keep up with their vigorous population growth: a female typically matures at 5-8 months, producing litters of 4-6 young up to twice a year. Their predators-mostly alligators, but also turtles, gar, cottonmouth water moccasins, hawks, owls, and eagles-can’t keep up either. As a result, these hungry rodents, each armed with inch-long orange incisors, are excavating the coastal marshes and riverbanks of the Gulf States. A single animal can eat up to 25% of its body weight in plants per day. Not only does this activity destroy coastal vegetation, but it also reduces habitat available for native muskrat and waterfowl. Nutria also venture inland, devouring rice, sugar cane, soybean, alfalfa and corn crops and burrowing through protective levees.

In addition to their voracious appetites, nutria carry a parasitic roundworm, or nematode, whose larva can burrow into human skin, causing a severe “marsh itch” or “nutria itch” requiring medical attention.

…even microscopic diseases.

Some invaders are much smaller, but no less destructive. Beaches everywhere are increasingly closed to clam and mussel harvest, with posted signs warning of red tide, the blooms of toxic single-celled algae that cause paralytic shellfish poisoning. These outbreaks have recently been associated with the global transport of ballast water in commercial vessels. A ship that takes on water in a bloom area may carry the algae to a new port, initiating a new outbreak there. Indeed, the resting stages of toxic algae have repeatedly been collected from the sediments in ballast tanks of ships sailing into Australian waters.

Viruses and bacteria are carried too: over 90% of the ships entering Chesapeake Bay carry epidemic cholera in their ballast tanks, and in 1991 cholera was introduced to Mobile Bay, Alabama, in the ballast water of a ship sailing from South America.

Not just in the sea

Aliens are also invading lakes and rivers, forests and fields. Paddling in the North American Great Lakes, you will encounter infestations of the European zebra mussel fouling beaches, boat hulls, piers, and power plant water intakes. The native plankton-eating fish you see in the water below you are competing with a tiny, spiny European water flea for food. That appealing-looking beach may in fact stink with piles of rotting alewife, an introduced coastal fish that also competes with native chub and whitefish. Salmonids, introduced partly to control alewife, are in turn eaten by introduced lamprey. And the lamprey prey on other fish, including steelhead (introduced) and walleye, whitefish, and burbot (native).

Fish introductions are altering freshwater foodwebs around the world, and waterways everywhere are clogged by introduced aquatic plants like purple loosestrife, hydrilla, water-hyacinth and Eurasian milfoil.

You will encounter plant and animal invaders ashore, too. In California, you may clamber over South African ice plant to pitch your tent under an Australian eucalyptus tree. When you unroll your sleeping pad in Hawai’i, you keep a wary eye out for South American fire ants; in South America, for Africanized killer bees; in Africa, for the thorns of Australian acacia trees; in Australia, for the dung of European sheep. It seems that certain species, like certain familiar fast-food joints or soda brands, may soon spread to every place you travel.

An accelerating problem

As invaders accumulate, they stamp out the uniqueness of an ecological community, and convert it to an international hodge-podge of aggressive competitors and predators. Over 40 species of marine invaders are found in Chesapeake Bay, over 50 in Coos Bay, Oregon, over 90 in Port Philip Bay, Australia, and over 100 in the Great Lakes, San Francisco Bay, and the eastern Mediterranean. As a unit, they represent one of the greatest threats to endangered species in the U.S., second only to habitat loss, to which they also contribute. Their estimated costs in control and eradication run into the billions of dollars annually, in the U.S. alone. And the flood of new arrivals shows no signs of slowing. How do these species become such a problem?

Planes, trains and automobiles

By definition, an invasion doesn’t happen by itself. It needs help, and that help – be it intentional or not -usually comes from humans. Every species is native to some place in the world where it belongs. Any species that travels to another place, a place it could not walk, swim, hop, jump or fly to by itself, is labeled introduced. And these species travel the same way we and our stuff do: in airplanes, boats, cars, trucks, packages, and sometimes even our pockets.

Accidental tourists

Let’s start with boats. Commercial ships carry thousands of tons of ballast water, port water that is pumped through hull openings into tanks that keep the ship stable at sea. This ballast water typically teems with tiny larvae, the microscopic stages of sea life, that are readily sucked up into a ballasting ship, transported farther and faster than they would naturally drift in ocean currents, and then emptied out into a new port. Zebra mussels are perhaps the most famous ballast-water invader, arriving in North America from Europe in the mid2980s and costing an estimated $5 billion in control efforts over 10 years.

Traveling in the other direction, the North American comb jelly, Mnemiopsis leidyi, sailed to the Black Sea at around the same time. Swimming like a predatory vacuum cleaner, this jelly’s population soared as it swallowed up larval fish and the microscopic organisms the fish eat. In the wake of this double whammy, commercial fisheries around the Black Sea crashed precipitously.

Historically, ships carried not water but dry ballast, port-side rocks and dirt full of plants, seeds, and insects, that was dumped out at the next beach, often a continent away. And unlike modern steel hulls coated with anti-foulants, older ships had wooden hulls riddled with species of ship worm, sponge, seasquirt, and seaweed that are now found the world over.

As ships were developed to carry water, so water was rerouted to carry ships. From the mid2800s to the mid2900s, water bodies that had been isolated for millennia were suddenly connected by canals. In 1869, the Suez Canal joined the Red and Mediterranean Seas; in 1914, the Panama Canal linked the Atlantic and Pacific; through the 1950s, the St. Lawrence waterway pushed west from the Atlantic to Lake Superior. Over 25,000 kilometers (15,500 miles) of canals now link the river cities of western Europe, stretching as far inland as Georgia. And where ships could sail, so too could-and did-fish swim and larvae drift.

Recreational boats, including kayaks, typically don’t carry water ballast, but they can carry a host of organisms on their hulls and trailers. Zebra mussels, for example, can survive out of water for days and their spread through lakes of North America is closely tied to patterns of boater traffic.

nvited invaders

Species introduced in ballast water are inadvertent hitchhikers, but other invaders are introduced on purpose. Like agriculture on land, the industry of aquaculture ships marketable species worldwide. Thus, Japanese oysters have been grown in Europe, Canada, the U.S., China, Korea, New Zealand and Australia. Mediterranean mussels are grown in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. In the U.S., Atlantic lobsters were introduced to the Pacific coast and Pacific clams to the Atlantic.