Offshore winds rank high as one of the greatest threats to a paddler. A minute or two of inattention can mean the differnce between getting to safety in the lee of the land and fighting a losing battle while being blown out to sea…..

Mark Seltzer, a 40-year-old computer consultant, and Marilyn Chan, a 43-year-old management specialist, were both passionate globetrotters. Savvy and cautious, the Canadian couple had traveled to nearly every corner of the planet. Mark had a vast collection of travel literature and had transformed his love for travel into an Internet business. Both shared a fascination for aboriginal culture, which had led them north to the Canadian Eastern Arctic a number of times. They wanted their long-time friends and travel companions, Phil King and Rosemary Waterston, to accompany them to a particularly special place in the new Canadian territory of Nunavut.

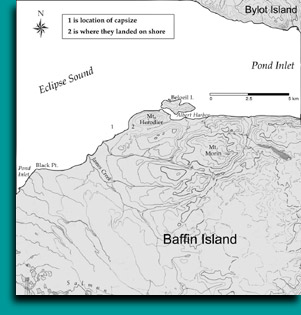

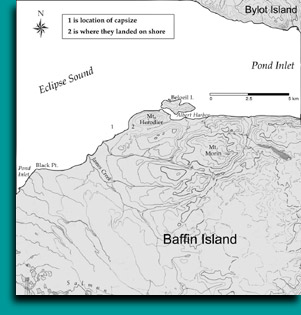

The two Toronto couples flew from Ontario during mid-July of 1998, and arrived at Pond Inlet, a town of 1100 residents on the rugged northern tip of Baffin Island (72° 41′ N, 77° 58′ W) 644 kilometers above the Arctic Circle. With its seasonal profusion of flora and fauna, spectacular scenery and affordable accessibility, the town of Pond Inlet had become a popular summertime destination for paddlers and hikers alike. The ice had broken up by the time they had arrived, so the four, deliberating whether they should hike or paddle, decided that kayaking was the easier option to get from Pond Inlet to Mt. Herodier close by.

Mark knew the local outfitter from a similar previous trip to Pond Inlet in the summer of 1996. They had kept up a friendship from a distance and had made arrangements for this trip to borrow either two double kayaks, or trekking gear. Mark, the driving force for the trip, was a little disappointed when the outfitter left to lead an expedition prior to making final lending arrangements, and the employee left in charge of the outfitter’s operation informed Mark the next day that only single kayaks remained. Mark was a little reluctant to discuss his concerns with the employee, so he settled for borrowing four Current Designs Solstice single kayaks.

The other three paddlers also had been looking forward to double kayaks, according to Phil. It was an important consideration given the imbalance of strength between the women and the men. Rosemary and Phil in particular had understood they were supposed to be in a double if they had opted to go kayaking instead of hiking, and had even rented a double only a few weeks prior in order to train in Toronto Harbour.

The group also borrowed four one-piece exposure suits, the standard apparel used by many boaters in the north. The suits offer flotation, warmth, and protection from salt spray or light rain but are not designed as immersion apparel for cold water. Other than paddles and skirts, no other rescue gear or electronic communication equipment was requested or offered. No one felt that the trip was of a level that required charts for navigation: Mt. Herodier was within easy walking distance of town. According to Phil, for anything more difficult the group would have hired licensed guides or simply opted not to kayak.

The paddlers didn’t ask to be apprised of any relevant weather information during this time and no forecast details were discussed or sought as the group took the kayaks.

Mark and Marilyn had paddled the exact same route on their previous trip, without incident, and would have shared with the group any route concerns they were aware of.

Mark was an advanced-level scuba diver, water-wise, and had always demonstrated good awareness and leadership in the out-of-doors. He had been paddling with Marilyn for two to three years. Phil and Rosemary’s only wilderness paddling had been one previous camping trip in an Ontario provincial park, but the two new paddlers were under no illusion about their experience levels. Nevertheless, everyone was satisfied at departure time that the trip was to be a safe, self-guided paddle in fairly sheltered waters during the brief window of prime paddling weather for Pond Inlet. The four paddlers would deal with deteriorating weather simply by getting off the water and staying ashore until conditions improved.

None of the paddlers thought their plan was foolhardy or would put them at risk. With enough gear loaded into the single kayaks for one to two nights, the four paddlers slipped away at about 11:00 on Thursday morning, July 16, from the pebble beach fronting the town of Pond Inlet. The waters were oily calm. The day was quite clear and relatively warm (10 degrees Celsius). Only a small amount of fog obscured Bylot Island, across Eclipse Sound. The route to Mt. Herodier was completely clear. Mark estimated that the 10-kilometer distance would take five hours at a slow pace with a rest stop. Everyone looked forward to reaching Mt. Herodier. Marilyn was an avid gardener and loved to see the fragile wildflower blossoms fighting the harsh elements in the valleys below Mt. Herodier. Kayaking for her, as well as the others, was merely a means to an end.

The waters in the area are subject to a tidal range of approximately six feet, ruling out difficulties with strong currents until they reached the Mt. Herodier headland. Beyond the headland, the inlet was still blocked by pack ice. The group progressed at a leisurely pace, keeping 100 to 200 meters offshore and passing tall, car-sized icebergs and increasing amounts of near-shore sheet ice. They had a great morning admiring the beauty around them and getting used to the gentle swell and being in the Arctic. At 1:30 they stopped along the western shore just past James Creek for a late lunch. They discussed setting up camp right then, but decided to take advantage of the ample travelling time that the continuous high arctic daylight provided.

By 2:30 the kayaks were back in the water. Marilyn and Rosemary both had been experiencing some lower back discomfort and so they both improvised backrests using sweatshirts wrapped in plastic bags. They were looking forward to reaching Mt. Herodier and rest. A French couple—Elizabeth Mitchell (originally from Canada) andPascal Ertlé—had left Pond Inlet in a double kayak at 2:00 that day headed for the same campsite area (as a jump-off point to Bylot Island). They had spoken with the four Canadians back in town and had watched them load their gear down at the beach. It didn’t take long for the experienced duo to overtake the group. By then they had the impression that the four Canadians might not be adequately prepared for Arctic paddling. Only Elizabeth spoke English. She wanted to express her concern that the four kayakers were paddling too far from shore. Noting the idyllic conditions and not wanting to stick her nose into the other people’s business, she just bid them farewell as they parted company.

By 2:30 the kayaks were back in the water. Marilyn and Rosemary both had been experiencing some lower back discomfort and so they both improvised backrests using sweatshirts wrapped in plastic bags. They were looking forward to reaching Mt. Herodier and rest. A French couple—Elizabeth Mitchell (originally from Canada) andPascal Ertlé—had left Pond Inlet in a double kayak at 2:00 that day headed for the same campsite area (as a jump-off point to Bylot Island). They had spoken with the four Canadians back in town and had watched them load their gear down at the beach. It didn’t take long for the experienced duo to overtake the group. By then they had the impression that the four Canadians might not be adequately prepared for Arctic paddling. Only Elizabeth spoke English. She wanted to express her concern that the four kayakers were paddling too far from shore. Noting the idyllic conditions and not wanting to stick her nose into the other people’s business, she just bid them farewell as they parted company.

Sometime in the late afternoon Mark, Marilyn, Phil and Rosemary approached the changing topography near the large bay formed by the elbow south of Mt. Herodier’s 765-meter peak. Rosemary felt she should keep well away from the near-shore ice, which she had read could roll over without warning and cause a sudden surge. The group did not meet to discuss concerns or form a consensus at this juncture. It wasn’t long before a strong offshore wind sprang up. Rosemary describes their initial positioning: “The coastline was rather scalloped [the accompanying map is not at a scale that could show this] with points of land between pebbled beaches. I could see where we were going and rather than staying close to the shore and having a longer route I cut across the last bay to make a straight line to the last point before landing. Once I got past that point of land I stopped paddling and took out the camera to take a picture of where we were going. I waited for Marilyn and Phil, who were closer to shore, to paddle into the shot. I asked Mark to move in closer to shore so I could take his picture but he joked that no, he ‘had paddled out to take a video of me taking a photo of Marilyn and Phil.”

At that time a large weather system out at sea was moving rapidly over Baffin’s northern tip. The wind accelerated through gaps in the mountainous topography and over icefields in the interior. After crossing the land it rushed out into Eclipse Sound. Rosemary continues: “As soon as I put the camera away I became aware that I was being blown away from the shore at a fast rate. The waves had also changed. Rather than facing the kayak they were now parallel to it and getting higher. I tried to turn my kayak to point into the waves and toward shore but wasn’t able to at all. Phil was yelling at us to come on and get in closer and I was shouting back that I was trying and I couldn’t; but he couldn’t hear me because the wind was carrying our voices, and us, away from shore. I was feeling very anxious and yelled to Mark that I was really uncomfortable because I couldn’t make the kayak go in the direction of shore.”

Within five minutes of the time that Rosemary was taking pictures, conditions on the water had deteriorated dramatically and it didn’t take long for things to unravel. Mark came right over, calmly instructing Rosemary not to panic and to keep paddling parallel to shore past the next point of land, where they might have more success turning the kayaks shoreward. Within only a few strokes a big wave from the direction of shore caused Rosemary to capsize. It all happened quickly. Her blade may have either caught a gust or a beam wave may have pushed her kayak sideways, over the paddle, tripping her as she set the paddle blade on the downwind side.

Rosemary had never practiced wet exits, but knew to pull the grab loop and exit forward. She describes the next moments: “I remember the water being very green as I came up for air. Mark was right there beside me when I surfaced and I assured him I was okay as he held my hands and got me to hold onto the side of his kayak. Both of our kayaks were parallel to the waves now and they pushed us farther from shore. He asked if I could climb up onto his kayak and I said I thought so. The next thing I remember is Mark coming up out of the water after his kayak capsized. His hat was gone though his glasses were still on. He looked so surprised.”

At this point, Phil remembers being a few meters from Marilyn and not much more than 50 meters from Mark and Rosemary. He doesn’t remember leaving his position closer to shore with Marilyn, until she alerted him that both Mark and Rosemary were in the water. Marilyn had been keeping a closer eye on the other two. Rosemary remembers Phil being right beside them as Mark surfaced but concludes that she and Mark must have been in the water for awhile: “I guess Mark and I must have bobbed around for awhile, holding onto our kayaks. I remember Mark fumbling with his video camera case, getting out his air horn and using it, but it was water-logged and didn’t make any sound. I think we had been blown to be about a quarter mile from shore at this time.”

The frigid Arctic waters were between one and two degrees Celsius. Rosemary, like the others in her group, had worn ski gear under her exposure suit, gloves on her hands, and a baseball cap. The exposure suits get their insulation and flotation capacity from an inner core of closed-cell foam. They fit like a pair of coveralls with cinch straps at the open cuffs and only provide protection for brief immersion times. Ice-cold water inundated Rosemary’s suit, leaving her susceptible to rapid hypothermia. Although her extra clothing may have prevented cold shock (See “Cold Shock,” SK, Spring 1991 ), she was still in a serious situation. Survival time in the Arctic is often measured in minutes. When Phil arrived, the two kayaks and paddlers were beside each other. Mark and Phil quickly instructed Rosemary to get onto the back of Phil’s kayak.

Rosemary was afraid that she would cause Phil to flip. Mark had already righted Rosemary’s kayak, so he then draped himself over it and reiterated instructions to Rosemary to go to the stern of Phil’s kayak and crawl up on the end of it. Without Mark’s instructions, Phil would not have known what to do. Rosemary explains what happened next: “As I moved over to Phil’s kayak I realized that my foot was wrapped up in the ropes attached to the kayak [the deck lines] that Mark was on-the kayak I had been paddling. I explained the problem and while I dunked backward under the water so my foot could come up, Mark turned around while still lying on the kayak to untangle my foot. Then I swam to Phil’s kayak and crawled onto it lengthwise so I was lying face down and holding onto the edge of the central hole [cockpit]. Phil was holding onto the empty capsized kayak and Mark told him that in this circumstance the book said we should let the empty kayak go.

“Mark and Rosemary’s kayaks, only moderately loaded with gear but swamped, were too heavy to drag one boat over the other to drain the water from it. There were no pumps aboard. Mark and Phil’s main concern was getting Rosemary out of the water and back to shore. Perhaps in his haste or lack of assisted rescue practice or knowledge of standard rescue procedures, Mark failed to suggest that they get Mark into the other righted kayak, and ultimately had Phil release the capsized kayak. With every second the situation was getting more desperate as the wind, despite what would seem to be a limited fetch, gained strength and the seas grew much worse.

Unfortunately, during the time it took to get Rosemary onto Phil’s back deck, Marilyn, who had been close to shore, was blown farther out to sea slightly and had drifted past the three other paddlers. She had somehow spun herself 180 degrees. She was beam-to-the-wind, as were the others, but facing opposite the direction the group had been paddling. As Rosemary recalled the scene, Marilyn turned her head, and “she shouted back to the other three that she didn’t know what to do. Mark told her to stay calm. Marilyn replied that she was calm, but didn’t know what to do. Mark told her to just stay upright.”

Phil was under great psychological duress at this juncture. With Rosemary shivering and precariously balanced on his rear deck, Phil had no other option in his mind than to head for shore with her. Mark agreed. Phil took one last look at his friends. Mark was clinging to the upright kayak by himself and Marilyn was drifting quickly farther offshore, fighting to keep her kayak upright.

Phil found the wind extraordinarily difficult to paddle against. Rosemary describes the difficulties: “Phil paddled to shore, cutting diagonally through the waves when he could. Because of the wind and the need to be careful, he had to go a long way east from where we had the accident, eventually landing on a little cove three beaches over. On the way waves kept breaking over me as I lay on the back of the kayak. I lifted my legs up out of the water to try to reduce the drag on the boat but I was very afraid of making the kayak unstable. I kept my head down and just kept saying ‘I’m OK’ over and over again so that Phil wouldn’t have to turn around to ensure I was all right. We almost tipped many times during the trip to shore. As we approached shore Phil yelled to the French couple on the beach that there had been an accident so they knew to get ready to help.”

Phil had spotted Elizabeth and Pascal on the beach. It took a few minutes before Elizabeth and Pascal could hear him shouting. As they hit the beach, Phil rushed to seek the couple’s assistance and advice, while Rosemary dragged the kayak up the shore and stumbled to empty needed gear, including a change of clothing. She then re-secured the hatches and tightened the straps, readying the kayak for Phil. The French couple did not hesitate to take to the water. Phil told Rosemary to get warm; then at great risk, Phil returned to his kayak, paddling out into the rough seas following behind the double.

Rosemary quickly dragged Phil’s gear bag to a dilapidated hunter’s shed nearby and changed into dry clothes. She checked her watch. It was 5:00. Phil eventually returned. The three had not been successful finding any sign of Mark or Marilyn where the incident had taken place. At significant risk, Elizabeth and Pascal had left the accident scene for Pond Inlet, safely negotiating the beam seas. They arrived exhausted and sore and immediately alerted authorities. From the beach back at the cove, Phil had spotted something rolling around in the waves, and went out one more time, alone, into virtually unmanageable seas. But what looked like the white hull of a kayak turned out to be just more ice. After his return, conditions had become so bad that he dared not go out again.

Under the circumstances, Rosemary took the liberty to look through the French couple’s gear, looking for anything that might help her get outside assistance or establish visual contact with the two missing friends. She found a pair of binoculars. Scrambling up an escarpment for a better view, Phil and Rosemary searched in vain for signs of their companions. Walking west along the beach, the couple had difficulty staying upright in the powerful wind funneling through the valley. Rosemary was knocked down by the wind a few times, and occasionally had to sit down just to catch her breath. Phil, increasingly anxious about the fate of the French couple, set out on foot for Pond Inlet later that evening. Less than an hour into the hike, he spotted two motorboats heading toward the bay and he ran back to the campsite. It was almost 9:00. Rosemary told the drivers where she had last seen Marilyn and Mark. The two boats went out to search, but one returned after 10 minutes with engine trouble. The driver, Norman, quickly radioed town for a replacement boat. He said that they couldn’t see anything in the accident area and that the waves downwind in the open channel were five meters high. Fog was also forming out in the channel and visibility would deteriorate further.

Phil and Rosemary remained on the wind-blown shore waiting in extremely stressful states. Around 11:30 PM another boat arrived. Despite Rosemary and Phil’s desire to assist with the search, the boat driver determined he would rather avoid the rough seas, so despite the couple’s protests, he would not venture out to the accident scene, or more importantly, downwind in deeper water. The boat motored carefully back to town closer to shore, dropping the couple off near the nursing station, where Rosemary was treated for mild hypothermia. Phil and Rosemary heard a helicopter leave town around 1:00 in the morning to join the boats in the search. In the high wind, waves, and cold mist that blanketed the Sound, the searchers found no trace of Mark and Marilyn.

In the days following the disappearance of Mark and Marilyn, a number of aircraft-including a military Hercules from Trenton, Ontario-participated in an extensive search. Days of poor visibility made the search difficult and eventually impossible. When the search resumed, flat ice sheets had moved into Eclipse Sound from the ice-choked entrance. Mark’s brother flew to Pond Inlet as soon as he could, contracted a helicopter, and then combed the 884-square kilometer search area in the Twin Otter he’d also hired. All the kayaks had white hulls, making it difficult for low-flight spotters to distinguish them amongst the ice.

The Hercules was recalled Monday morning. By Wednesday the family called off their search efforts after completing inspection of the full coastline perimeter. There was no further hope that Mark or Marilyn had survived the frigid Arctic water temperatures or made it to landfall. Locals eventually found all three kayaks. Two weeks after the accident, Mark’s body was found in the Sound. His bright orange exposure suit was still intact. Because the suit would have been easy for the searchers to spot, it is likely that Mark may have been pulled under the ice during the search.

A dry suit with proper insulation worn underneath it is the only apparel that realistically provides an adequate amount of survival time in Arctic waters for group rescue and post-rescue complications. Wetsuits will work but can be a bit restrictive to paddling in the thickness usually required for protection in near-freezing waters. Marine survival suits, often used by marine workers in Alaska in the event they have to abandon ship, are watertight but too cumbersome for kayakers.

Exposure suits like those used by the paddlers do not provide enough protection once an immersion takes place in near-freezing water. These suits lack cuff and neck seals, and permit water to enter and make quick and direct contact with a paddler’s skin. Only a sealed dry suit, combined with insulating undergarments, maintains a layer of air between the fabric and the paddler’s skin, which acts as a barrier to heat loss. Although exposure suits do add to total survival time in near-freezing water, actual functional survival time is severely diminished by the ready infiltration of water. Nursing staff at the First Aid Station assured Rosemary that Mark would have a good chance of being found alive in the water during the night as he was wearing his suit. This is a common misconception about the ability of exposure suits in very cold water, although improved models do now incorporate neoprene wrist cuffs, ankle and thigh cinch straps, and stowaway hoods, which add somewhat to functional survival time.

Given the paddlers’ proximity to Pond Inlet, distress signals may have brought quicker aid to the group once they encountered problems. Aerial flares would be less effective with the continuous Arctic daylight and an EPIRB-type device likely would have brought help but far too late. A radio may have proven useful. High frequency (HF) and VHF radio contact is a common form of summoning help in many areas of northern Canada. In Pond Inlet, however, there are no repeater stations and the locals do not monitor VHF. There, HF and CB radio are the norm. The telephone remains the most common way to summon specific help, so hunters often carry satellite phones. There is an airport located near the town, which can coordinate weather-dependent aircraft evacuations and a small RCMP detachment for all emergency concerns or updating float or travel plans. The ability to call for emergency assistance is an important consideration not to be ignored in the Arctic even for short trips.

Even the experienced couple in the tandem kayak had no way of quickly securing outside help. It is only prudent to ask what the communication implications are for the area you are paddling in: ranges, the frequencies locally monitored, and important telephone numbers where applicable. Some Arctic outfitters have expanded their rental options to include items like Spilsbury SBX 11 HF radios (too bulky for paddlers) and satellite phones (check with the service provider for coverage range). It is also important to have contingency plans in place. Help in the Arctic can be slow to arrive, delayed due to weather, and costly, so even if you can make a call for help you need to be prepared to take care of your group until aid arrives. Usually paddlers research an intended area of travel to find out if a small weather radio would pick up marine weather broadcasts or warnings in lieu of a more expensive VHF radio; however, in this case, the closest active forecasting facility was 550 kilometers away in Resolute-leaving the paddlers more or less on their own.

One item often excluded by outfitters—and by self-supported paddlers themselves—are towlines. An easily deployable towline would have given Phil the option to hook onto Marilyn’s kayak and provide the assistance she needed before conditions worsened. Carrying some form of basic towline is always a good idea. Neither Marilyn nor Rosemary would have had the strength, unaided, to regain shore in single kayaks. If the two stronger paddlers had hooked onto the weaker paddlers at the first hint of changing conditions, it also may have helped Marilyn and Rosemary to get their bows turned into the wind.

Of course, if the two couples had been in tandem doubles, there is little doubt in Phil’s mind that the two men could have powered both boats to shore safely

.

Experience and environment weigh heavily in this incident. Constable Burton, representing the RCMP detachment in Pond Inlet, indicated that the waters around Mt. Herodier are known for rough conditions. Severe winds from Greenland divert around Mt. Herodier and grow more intense in the vicinity around the mountain. The strong and sudden winds can catch even experienced kayakers off guard. Burton admitted that Pond Inlet is popular with kayakers precisely because the winds are infrequent and usually out of the East so the water in the lee of the land is calm. It is not unusual for paddlers visiting Pond Inlet to forego hiring professional guides.

The paddlers lacked the experience and knowledge to understand the risks of paddling in the Arctic and of approaching a headland like Mt. Herodier. Offshore winds rank high as one of the greatest threats to a paddler. Whether it is a katabatic gravity wind or (as in this group’s case) wind that is the result of a weather-related pressure gradient, the farther out you are pushed, the worse it gets. A minute or two of inattention can mean the difference between getting to safety in the lee of the land and fighting a losing battle while being blown out to sea. It is best to avoid the exposure to offshore winds by keeping close to shore and being especially wary of winds funneling through low spots in the shoreline topography.

The difference in wind speed between land and offshore can be as high as a factor of 50%. In an offshore wind it can be very difficult to recognize how rough it is farther away from shore, as you see only the backs of the waves. They may appear smooth while hiding the churning white foam on their downwind faces.

Although the group was given no warnings before leaving Pond Inlet, they also failed to do their homework and to ask pertinent questions. Moreover, a team of experienced paddlers would normally keep a tight formation approaching a significant topographical feature, having already anticipated the possibility of associated wind compression, then headed much closer to shore at the slightest hint of an offshore wind. The four friends, while seasoned travelers, were not experienced sea kayakers. In this situation the outfitter was not acting in his professional role as guide or equipment provider. He was doing a favor for a friend by lending him some kayaks. His employee was also making the four kayaks available outside of the standard rental process. Both may have assumed the group was better experienced than they actually were.

If the four paddlers had had more experience, a number of things might have proven different once trouble started. Rosemary would have known to be wary of presenting the flat of her blade on the upwind side to the gusts of wind and also to lean into the waves as each one hit, taking advantage of the upward movement of water on the wave face. Turning a sea kayak into strong upwind conditions is never an easy task. Mark could have paddled slightly ahead of Rosemary on her windward side, shielding her bow while she tried to turn her boat into the wind. Rosemary could have raised her rudder onto the rear deck. With a rudder deployed, the stern of a kayak will not slip downwind, making it more difficult, if not impossible, to get the bow turned into the wind. If she had raised the rudder and paddled hard and fast straight across the wind she could have taken advantage of a kayak’s tendency to weathercock: with more boat speed the turbulence at the stern would allow it to slip downwind, causing her kayak to turn with less effort into the wind. She would take advantage of the weathercocking by using sweep strokes on the downwind side.

Rosemary also could have shifted her hands along the paddle shaft toward the upwind blade, thereby allowing greater leverage for wide downwind sweep strokes, and paddled only on the downwind side. Performing this kind of a turn with a strong lean that places the kayak further on edge makes for an even tighter turn. These are all skills learned with time and training.

It is rarely a good idea to let a kayak go. Well-practiced assisted rescues may have allowed Rosemary and Mark to get back into their kayaks after their capsizes. Bailers could have been improvised from whatever might have been close at hand, including items such as saucepans, rain hats, a day bag, etc.

This group was overwhelmed by sudden and severe winds that, although they may be uncommon, should be expected in the waters near Pond Inlet. It is always the responsibility of the paddler to be fully prepared, to avoid problems before they become insurmountable, and to be prepared and able to accomplish their own rescues. In the final analysis it is the paddler who needs to research the intended area of travel, possess the boat handling and rescue skills to deal with the environment, and have back-up equipment and plans in place. This group of paddlers thought their short outing would be easy, no more difficult than a paddle in less extreme latitudes. Phil relates his feelings, “I just wish someone had tapped us all on our shoulders and said, ‘Hey, this is the Arctic, you need to be ten times as careful up here.'”

The deaths of Mark and Marilyn were a terrible tragedy. The story is compelling because it could have happened to anyone-suddenly changing conditions can catch paddlers of all experience levels off guard. Even experts would have been hard-pressed to perform some of the rescues or turn their kayaks into the fierce wind that hit the group. Both Phil and Rosemary were extremely lucky to survive-Phil doubly so.

Nicholas Mark Seltzer was awarded the Governor General of Canada’s Medal of Bravery (posthumously in 1999) for his “act of bravery in hazardous circumstances.” Phillip King, Elizabeth Mitchell and Pascal Ertlé each received a commendation from the Governor General for “an act of great merit in providing assistance to others in a selfless manner.”

I had decided to go kayaking after work one day, and that morning, I’d carefully loaded my kayak onto my cartop racks, strapped it down and tied bow and stern lines to the car. I had driven 15 miles, including several miles on the freeway, and I was only one stoplight away from work. As I pulled forward in the line of waiting cars, I heard what sounded like a horrific automobile crash. The front of my boat lurched down toward the hood of my car, and small pieces of fiberglass floated down like falling snow sprinkling my -windshield.

I had decided to go kayaking after work one day, and that morning, I’d carefully loaded my kayak onto my cartop racks, strapped it down and tied bow and stern lines to the car. I had driven 15 miles, including several miles on the freeway, and I was only one stoplight away from work. As I pulled forward in the line of waiting cars, I heard what sounded like a horrific automobile crash. The front of my boat lurched down toward the hood of my car, and small pieces of fiberglass floated down like falling snow sprinkling my -windshield.

By 2:30 the kayaks were back in the water. Marilyn and Rosemary both had been experiencing some lower back discomfort and so they both improvised backrests using sweatshirts wrapped in plastic bags. They were looking forward to reaching Mt. Herodier and rest. A French couple—Elizabeth Mitchell (originally from Canada) andPascal Ertlé—had left Pond Inlet in a double kayak at 2:00 that day headed for the same campsite area (as a jump-off point to Bylot Island). They had spoken with the four Canadians back in town and had watched them load their gear down at the beach. It didn’t take long for the experienced duo to overtake the group. By then they had the impression that the four Canadians might not be adequately prepared for Arctic paddling. Only Elizabeth spoke English. She wanted to express her concern that the four kayakers were paddling too far from shore. Noting the idyllic conditions and not wanting to stick her nose into the other people’s business, she just bid them farewell as they parted company.

By 2:30 the kayaks were back in the water. Marilyn and Rosemary both had been experiencing some lower back discomfort and so they both improvised backrests using sweatshirts wrapped in plastic bags. They were looking forward to reaching Mt. Herodier and rest. A French couple—Elizabeth Mitchell (originally from Canada) andPascal Ertlé—had left Pond Inlet in a double kayak at 2:00 that day headed for the same campsite area (as a jump-off point to Bylot Island). They had spoken with the four Canadians back in town and had watched them load their gear down at the beach. It didn’t take long for the experienced duo to overtake the group. By then they had the impression that the four Canadians might not be adequately prepared for Arctic paddling. Only Elizabeth spoke English. She wanted to express her concern that the four kayakers were paddling too far from shore. Noting the idyllic conditions and not wanting to stick her nose into the other people’s business, she just bid them farewell as they parted company. If you’re into making your gear do double duty, you can add a matching female buckle half to the end of one of the side anchoring straps, and you’ll have a first-rate fanny pack. The foam sewn into the bottom of the Turtle Back for flotation makes it quite comfortable when it’s worn around the waist.

If you’re into making your gear do double duty, you can add a matching female buckle half to the end of one of the side anchoring straps, and you’ll have a first-rate fanny pack. The foam sewn into the bottom of the Turtle Back for flotation makes it quite comfortable when it’s worn around the waist.  The Wheeleez tires aren’t as free rolling on pavement as other wheels, but they are certainly the quietest. They don’t transmit any vibration to the kayak.

The Wheeleez tires aren’t as free rolling on pavement as other wheels, but they are certainly the quietest. They don’t transmit any vibration to the kayak.

can be hard to pick out from the background, and it’s their motion that makes them stand out. Beyond 75 yards, the Ion blades fade into invisibility. The blades will continue to glow all night long, and after you get to camp, they make a great bedside “table” for your flashlight, glasses and other things that the tent fairy often hides after you’ve fallen asleep.

can be hard to pick out from the background, and it’s their motion that makes them stand out. Beyond 75 yards, the Ion blades fade into invisibility. The blades will continue to glow all night long, and after you get to camp, they make a great bedside “table” for your flashlight, glasses and other things that the tent fairy often hides after you’ve fallen asleep.

The suit is comfortable to wear and mates well with a spray skirt. The back-entry zipper makes the suit easy to get on and off, and it doesn’t clutter up the front of the suit. The suit lends itself well to the range of motion required by paddling and rolling. The ends of the zipper do, however, press against the backs of your arms while you’re paddling. It may feel strange and slightly annoying at first but is soon forgotten. That the Aleutian keeps you dry is to be expected. In its details—the right materials for the job in the right places—are the reminders that the Aleutian EXP is money well spent.

The suit is comfortable to wear and mates well with a spray skirt. The back-entry zipper makes the suit easy to get on and off, and it doesn’t clutter up the front of the suit. The suit lends itself well to the range of motion required by paddling and rolling. The ends of the zipper do, however, press against the backs of your arms while you’re paddling. It may feel strange and slightly annoying at first but is soon forgotten. That the Aleutian keeps you dry is to be expected. In its details—the right materials for the job in the right places—are the reminders that the Aleutian EXP is money well spent. The bottom of the cagoule has a circumference of roughly 105 inches and should fit even the larger coamings of touring kayaks. In our tests, the cut of the cagoule made for a good fit over the spray deck without any excess fabric. Having the extra layer on didn’t get in the way of paddling or even rolling. Keep in mind you shouldn’t cover the spray skirt grab loop with the cagoule.

The bottom of the cagoule has a circumference of roughly 105 inches and should fit even the larger coamings of touring kayaks. In our tests, the cut of the cagoule made for a good fit over the spray deck without any excess fabric. Having the extra layer on didn’t get in the way of paddling or even rolling. Keep in mind you shouldn’t cover the spray skirt grab loop with the cagoule.