I already carry a PLB, a VHF and a GPS aboard my kayak—and I put a lot of faith in my three-letter electronic gadgets—so when I was asked to try a SPOT Satellite Personal Tracker, I eyed it and its gratuitous vowel with suspicion. When I added a cell phone in a waterproof bag to my kit of electronics, I figured I had all of my bases covered—so why would I want to carry a SPOT?

There’ve been many times when I’ve wanted to spend a couple of extra hours out on the water but couldn’t reach home on my cell phone. I just had to turn around to meet my float-plan deadlines. I’m not going to be packing an expensive satellite phone anytime soon, and I certainly won’t be calling up the coast guard on my VHF radio to ask them to call home and explain to my other half that the surf’s too good to come home just yet. There are also times when minor emergencies are best taken care of by friends and family. If I were to lose both my paddles or punch a big hole in my kayak playing in the surf, setting off my personal locator beacon (PLB) to call in the cavalry would be overkill if I could have a friend retrieve me.

This is where SPOT, the “world’s first satellite messenger” can come in very handy. SPOT tracks your global positioning service (GPS) coordinates and can transmit your position and simple “I’m OK” message to your float-plan holder via a satellite network. Those satellites relay the information to specific land-based satellite antennas around the world. The antennas can relay your message, as required, to the Internet, a cell phone network, an emergency call center or all three, depending on the signal you choose to send. SPOT Inc., based in Milpitas, California, is a subsidiary of Globalstar, a corporation that maintains a network of communications satellites.

The SPOT unit sells for $149.99 at most marine or outdoor stores (and some stores are now discounting the units). The annual charge for the required basic satellite service subscription is $99. That level of service gets you the Alert 9-1-1 emergency response to call for search and rescue (SAR) services; a “SPOTchecking” function, which lets you send a notice to your contacts to tell them where you are and that you’re OK; and the ability to indicate your position and signal for help from friends and family rather than from SAR.

For an additional $49.99 a year, you can purchase the tracking upgrade option, which is when all the fun really starts. With the tracking option, or “SPOTcasting,” SPOT will automatically send your location to your online SPOT account every 10 minutes. Folks at home can then follow your progress via Google Maps. To extend battery life, SPOT is programmed to run the tracking for 24 hours. To reactivate, you push SPOT’s OK button.

After purchasing SPOT, you have to register the unit online with the company and set up a personal Internet account. You list the cell phone numbers and email addresses of those you wish to be on your “SPOT team” and indicate which messages you wish them to receive. Each time you activate your Alert 9-1-1, ask for help from your team or check-in, your entire team, or specific individuals on your team, will receive an Internet message and/or a preprogrammed Short Message Service (SMS) cell phone text message. And depending on the nature of your trip or wherever in the world you are, you can log on to the SPOT website and change your SPOT team members to keep current with your needs and location. You can also add supplementary information—medical condition or boat color, for example—which will be passed on to the appropriate emergency services. I added a description of my kayak.

Setting up your personal account information on SPOT’s website can be challenging. I called SPOT’s customer service a couple of times to get help with what information was needed for the account. For example, on your “personal account” page, you are asked for primary and secondary personal contact numbers—for this page, use your own personal numbers (e.g., your cell and home or work numbers). Your “default” page is where you list your friends’ and family’s email addresses and phone numbers to receive your OK or Help messages. These numbers cannot be the same as those on your personal account page, so if you’re having someone in your household act as an emergency contact, you cannot list your home phone with your personal information. The emergency numbers on your default page are the ones the Emergency Response Center (ERC) will call. Overall, SPOT Inc. could improve the intuitiveness of its web interface.

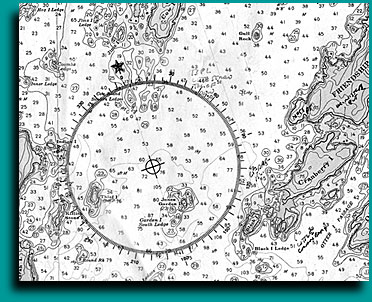

Like any GPS-enabled device, the front of the unit needs to be facing skyward for it to work. SPOT uses GPS satellites to determine a user’s location and a separate commercial communications satellite network to send its messages. The second satellite network is the same one that Globalstar satellite phones use, but SPOT transmits in the more reliable Globalstar Simplex mode. This one-way communication system has a 99 percent completion rate and is widely used to track the movement of shipping containers, ships, trucks and freight.

SPOT can be used around the world, including all the continental United States, most of Canada, Mexico, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, northern Africa, northeastern Asia, portions of South America and thousands of offshore miles around those continents. (Arctic and Antarctic regions, central and southern Africa, India, Southeast Asia and China are not covered. See www.-findmespot.com for a coverage-area map.) A Canadian paddling around Tasmania in February 2008 issued a distress signal with his Canada-registered SPOT. Canadian authorities advised Australian emergency services of his SPOT 9-1-1 signal, and rescuers reached the paddler five hours after the SPOT signal was transmitted. Local boaters pulled the kayaker from the water just as a SAR rescue helicopter arrived. The helicopter crew treated the kayaker and transported him to a hospital.

The SPOT device is bright orange and has a black rubber material along its perimeter for a nonslip grip. Measuring 4.38 x 2.75 x 1.5 inches (111 mm x 70 mm x 38 mm) and weighing 7.37 ounces (209 grams), SPOT is small enough and light enough to be unobtrusive when clipped to you or your boat. The battery compartment is secured by two screws fitted with wire bails, with a third screw for a belt clip. The belt clip screw had a tendency to loosen, and you may lose the unit if you rely on the clip rather than a pocket to secure the SPOT unit. A cord tied around the clip and through the bail would keep the screw from backing out. You can clip the unit to the deck of your kayak, but the best practice is to keep emergency equipment securely attached to yourself. You’ll still have it if you happen to get separated from your boat.

The SPOT unit floats and is waterproof to a depth of one meter for up to 30 minutes. It’s also temperature tolerant and shockproof. Power is supplied by AA lithium batteries (included), which should last stored for several years; under normal usage, with just the power on, they’re good for about one year. Activation of the tracking mode will drop battery life down to about 14 days, and the 9-1-1 mode will drop it to around seven consecutive days. A set of batteries should allow 1,900 messages sent by the OK button.

SPOT’s manual states: “With a perfect view of the entire sky, the SPOT network is designed to successfully send virtually any message.” Only if you can achieve this “perfect view of the entire sky”—which may not be easy for a kayaker meandering through Florida’s Everglades—can you be assured that the majority of your messages will go through. I confirmed this with my own testing. Over a couple of months of using SPOT, I found that it did not work sitting on the passenger seat of my car. OK messages I sent did not result in emails being sent to my account. SPOT did work sitting atop the car’s dashboard when I was driving in open areas. In an urban setting, OK messages sent while I was driving or walking city streets surrounded by lots of tall buildings did not always get through. Heavily wooded areas may yield similar results. SPOT worked sitting in my tent with a few palms overhead, but it didn’t from the pocket of my PFD. To increase reliability in areas where the view of the sky is partially obscured, SPOT is programmed to make multiple transmissions for each message mode used. SPOT will transmit a 9-1-1 distress signal every five minutes until cancelled or the battery runs out of power—again, about seven days. (By comparison, PLBs typically send out a distress signal for only 24 hours.)

The only place I found to clip the SPOT unit to my PDF that still afforded a clear signal was on my upper shoulder device holder where I normally attach my strobe light. Because I can’t see the unit in that position, I needed to be very familiar with SPOT’s layout to avoid confusing the OK button for the Help or Alert 9-1-1 buttons. The buttons are placed intuitively enough—Help and 9-1-1 are outer left and right, and the On/Off and OK buttons you regularly use are centrally lower and close together. To guard against unintentional activation of the 9-1-1 button, it has a raised ring around it so it feels different from the other buttons. It also needs to be depressed for three seconds to activate it. While some users have taped small bits of stiff plastic over the 9-1-1 button to reduce the risk of triggering a false alarm, SPOT reports that they’ve had no 9-1-1 signals transmitted by anything other than someone intentionally pushing the button. The 9-1-1 transmission can be cancelled by pushing the button again. A solid red light will shine indicating the cancellation message has been sent. Following up with a few OK transmissions will help confirm the cancellation of the emergency call.

When the unit is turned on, a green light above the On/Off button will flash every three seconds. When you push the OK button, a green light above it will also flash. The light will be on continuously as transmissions are sent. When the OK signal is received, your SPOT team receives an email similar to this:

SPOT Check OK.

Unit Number: [the serial number of your SPOT]

Latitude: 27.623

Longitude: -82.7098

Nearest Town from unit location: Fort De Soto, United States

Distance to the nearest town: 3 km(s)

Time in GMT the message was sent: 02/08/2008 23:14:07

[and a URL link to a Google Map, showing exactly where you are]

The corresponding message received as an SMS on your SPOT team members’ cell phones will look like:

SPOT Check OK.

Latitude: 27.623

Longitude: -82.7098

Fri, Feb 8, 11.14 pm [EST]

Originally, those who wished to track you using the Google Maps technology needed password access to your SPOT Internet account. Now SPOT is beta testing a “share page.” So if you’re leading a kayaking trip for a week or so, you can now set up a temporary account with up to 10 email addresses or cell-phone numbers of the family and friends paddling with you. By providing them with your account’s URL, they can track your group, password free.

I have to admit, at first I found the patterns of flashing lights on the front of the unit a bit confusing and needed to refer to the manual for what each pattern of blinks meant. SPOT indicates when it’s sending a message and will stop blinking when the transmission is complete. Because the SPOT is a Simplex device (one way—transmit only), it doesn’t let you know whether the transmission has been received or not. Just as it is with a PLB or emergency position-indicating radio beacon (EPIRB) distress signal, you have no indication whether or not help is indeed on its way. If you press the Alert 9-1-1 button in an emergency, SPOT will acquire your GPS coordinates and send them along with a distress message to the GEOS International ERC in Houston, Texas, every five minutes until cancelled. The ERC notifies the appropriate emergency responders based on your location (e.g., contacting 9-1-1 responders in North America and 1-1-2 responders in European Union nations) and personal information, as well as notifying your emergency contact person(s) about the receipt of a distress signal. Even if SPOT cannot acquire its location from the GPS network, it will still transmit a distress signal—without exact location—to the ERC. The ERC will notify your contacts of the signal, and continue to monitor the network for further transmissions that may include the GPS data. Like a PLB, SPOT’s 9-1-1 distress signal is a feature that cannot be tested.

I put SPOT to the test during this year’s Watertribe Everglades Challenge (www.watertribe.com), a 300-plus-mile kayak and small-boat race from Florida’s Tampa Bay to Key Largo. A week prior to the race, I discovered that my SPOT was malfunctioning—every time I pressed the OK button, instead of green confirmation flashes I got red flashes. SPOT Inc. tells me that they have only a 1 percent malfunction rate overall. They mailed me a replacement unit overnight to ensure that I would have one in time and updated my personal SPOT account.

I had my SPOT turned on for the entire five days of the race. For two days, I tested the unit using the tracking mode, then I switched from the automatic tracking mode and used the manual OK mode for the remainder of the race. The usefulness of the unit really became clear to me and my SPOT team while navigating Everglades National Park, where cell phone coverage is nonexistent. Because of the challenging weather conditions, I had to make a couple of course changes from my pre-race plan. I pressed the OK button at every new heading I took so my family and a race reporter could see on Google Earth exactly where I was. I finished the race a day earlier than I had planned and did not have a place to stay that night. My partner had watched my progress through the received SPOT emails and, knowing I was ahead of schedule, phoned the hotel to rebook my room for early arrival. I have SPOT to thank for the hot shower and comfortable bed I had waiting for me after a very tiring, wet race!

SPOT is truly a step forward in personal electronics and safety. As with any emergency device, you need to be wary of relying on it (or any other single device) to help save you in a difficult situation. Training and other essential safety equipment should remain as priorities. Using good judgment to keep you out of an emergency situation is probably more important than packing the technology that might help you after you get into one.

If you do much kayaking, there’s no question you should have some kind of emergency alert system carried on you. The only thing I’m still mulling over is whether I can bet my life on SPOT or on my 406 MHz PLB as a fail-safe form of distress signal. PLBs have been tried and tested for many years in rescue situations all around the world. SPOT is new, but rescues are already being credited to it. For now, I’m still packing my PLB for an extra margin of safety, but SPOT has earned its place in my must-have equipment as the best way of letting my family and friends track my progress. For the comfort that provides my family and me, SPOT is without equal.

Kristen Greenaway is a Kiwi now living and paddling in North Carolina. In July of 2009, she plans to enter the inaugural Yukon 1000 Canoe & Kayak Race, which requires each contestant to carry a SPOT—for emergency use and to allow race officials to track progress and enforce mandatory layovers.

SPOT Satellite Personal Tracker

$149.99 plus $99 annual basic service charge; optional $49.99 for annual tracking upgrade

SPOT Inc.

866-651-7768 or 408-933-4518