The sun was dropping fast as we hurriedly paddled our way among the low islands of mangrove trees. We were aiming for West Pass, a half mile distant. To our right, the Ferguson River flowed into Chokoloskee Bay behind a platoon of individual mangroves. I kept glancing back and forth between the nautical chart and the compass. It was imperative that we keep track of our position on the nautical chart, as we were paddling in Florida’s Ten Thousand Islands, a literal maze of mangrove trees rooted to the shallow ocean floor. They range from a single tree rising from the sea to thousands of mangroves, forming islands like jigsaw-puzzles measuring hundreds of acres in size.

Ahead, I spotted swiftly flowing water between two mangrove islands: West Pass Channel. Bill, my paddling partner, entered the channel first, and I followed. The push of the incoming tide immediately slowed us down. Moments later, we emerged into the Gulf of Mexico. The sun shone in a freshly washed cobalt-blue sky over two-foot waves that stretched westward as far as the eye could see.

Earlier in the day, a powerful thunderstorm had rumbled through just as we had arrived at the Gulf Coast Ranger Station, near Everglades City. The storm had delayed our departure by two hours and forced us to paddle rapidly to make it to our destination by nightfall. Three hours into the paddle, as we skirted the shallow northern shoreline of Tiger Key, we raised the rudders on the sea kayaks to prevent scraping the sandy bottom. One last turn around a narrow peninsula led onto Tiger Key beach.

Sea grape trees, lit red by the dying sun, hunched over the upper end of the sloped beach.

These generally low-slung coastal trees have large, round, shiny leaves that are leathery, to tolerate the strong sun. They produce a grape-like fruit in the fall, which settlers of a century ago gathered and made into jelly. I sat for a few moments in my kayak, relaxing my arms, and enjoying the cessation of repetitive motion. Moments later, the sun dropped below the horizon. We’d completed the seven-mile West Pass Route before dark.

I was on the tail end of a scouting expedition for a paddling guidebook I was writing. I had already spent most of the winter paddling the Everglades, and had been adventuring down here for a decade. My friend and fellow Tennessean, Bill “Worldwide” Armstrong, had flown down from our hometown of Knoxville to join me for the trip. *The beach of Tiger Key is one of 52 designated backcountry campsites within the confines of Everglades National Park. It lies at the extreme northern end of the preserve, where the fresh water of the mainland flows through sawgrass into innumerable channels, which in turn gather in rich estuaries to form rivers leading to the Gulf and thousands of outer islands. Most of the outer islands are very small, yet hundreds are five acres or more, like Tiger Key.

Our trip would take us through the Ten Thousand Islands area. We would be paddling 11 miles down the Gulf to Pavilion Key. The next day would be a short four miles to Mormon Key, allowing time for exploration and fishing. Then we would turn inland up the Chatham River and pass the old Watson Place, a pioneer homestead, before staying at Sweetwater Creek. We would then head north on the Wilderness Waterway seven miles to Sunday Bay, and finish our trip back at the Gulf Coast Ranger Station, for a total of 53 miles.

Loop possibilities in the Ten Thousand Islands are limited only by the paddler’s imagination, considering the numerous rivers, bay and creeks of the area. Sixteen backcountry campsites in the

vicinity, open to boaters of all stripes, make desirable routes all the more feasible. There are three types of backcountry campsites in Everglades National Park: beach campsites, ground campsites and chickees. Beach campsites are located along the Gulf of Mexico, either on the mainland or on islands.

These beaches are formed by the disintegration of millions upon millions of shells, pulverized over time by wave action, and deposited on the shores of the keys and coast. They have a yellowish-white tint, and are not as fine as the sands of the northern Gulf, where the sand is deposited from the Southern Appalachian Mountains, then bleached sugar white.

Ground campsites are primarily located inland. They are situated on discarded mounds of shells, remnants of numerous generations of Calusa Indians who roamed the Everglades since pre-Columbian days. The Calusa wandered Florida from Lake Okeechobee south to Cape Sable, the southwestern tip of the Florida mainland. They paddled long canoes made from hollowed-out cypress logs to collect food from the abundance of saltwater, freshwater and land sources. The shell mounds they created provided a place to camp where there was no land, and they still serve this purpose today.

The third type of campsite, chickees, are built in areas where there is no dry land. These are elevated platforms on stilts with open sides and a sloped metal roof. Vault toilets are attached to the platform by a gangway. Chickees are named after Calusa thatch huts of similar design that they constructed on terra firma. In their day, the Calusa would keep a smoldering fire of black mangrove going in the chickees to keep out the mosquitoes, and they slept on a raised platform beneath the thatch to catch the breezes.

Many first-time Everglades paddlers are surprised at what really comprises the Everglades. There are two preconceived notions of the Everglades: The first image is of the Everglades as jungle, with tall trees filled with exotic birds, and snakes dangle from limbs hanging over alligator-filled waters. This image actually comes close to describing the Big Cypress Swamp, which lies directly north of the Everglades.

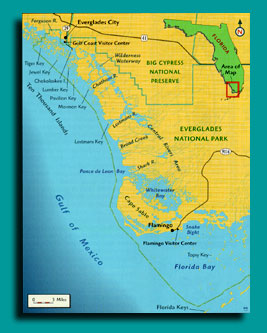

The second image, the Everglades as a sea of water and grass shimmering to the horizon, with the sun mercilessly beating down, is partly accurate, but describes none of this park’s paddling area. There are numerous other ecosystems here, such as pine islands where deer thrive and panthers may roam, or tropical hardwood hammocks where trees like the strangler fig lend a lush, tropical Southern Florida look. Cypress sloughs and coastal prairies are other ecosystems found here. For the paddler, there are two primary ecosystems: coastal mangrove swamps and the Gulf of Mexico, also known as the “outside.” Of these, the mangrove swamp dominates the paddling area. With the perpetual mixing of fresh and salt waters, mangrove trees thrive here, forming the largest, thickest, tallest mangrove forest on the face of the planet. Mangroves exceed 100 feet in height along the Shark River. Extending more than 90 miles from north to south and 50 miles west to east, Everglades National Park (ENP) is the largest nature preserve east of the Mississippi; in the lower 48 states, it’s second in size only to Death Valley National Park. The paddling area of ENP stretches 90 miles along the Gulf and 20 or so miles inland. There are more than 400 miles of commonly paddled routes within the ENP. All of these routes connect the two primary launch points, Flamingo and Everglades City, with backcountry campsites.

From Flamingo, paddlers can explore the keys of Florida Bay, the aptly named Whitewater Bay, Cape Sable and the southern, interior rivers. The Central Rivers Area is at least a day’s paddle away from Flamingo. From Everglades City in the north, paddlers can explore the Ten Thousand Islands, the northern Gulf and the interior bays and creeks of the north end. The Central Rivers Area is at least a day’s paddle away to the south.

The Marjory Stoneman Douglas Wilderness covers about 80 percent of the total ENP. In 1947, Douglas wrote Everglades: Sea of Grass, which was instrumental in informing the public about the uniqueness of the Everglades. Douglas’ book launched the move to establish the Everglades as a national park. *Unfortunately, when designating the ENP as a Wilderness Area in 1978, the water portions of the park were exempted from the “no motorized vehicles” rule of the Wilderness Act. This means that powerboats are allowed in the wilderness, in most of the paddling areas of the Everglades. I have not found this to be a distraction, since the scenery and overall experience simply overwhelm a few boats whizzing by. The farther you get from Everglades City or Flamingo, the fewer boats you will see.

Navigating can be challenging in this seemingly endless profusion of bays, ponds, creeks, inlets, lakes, rivers, undulating shorelines and keys. The horizon is unbroken by elevated features, such as mountain peaks or river valleys, and mangroves form a green coast that can appear to be the same at different locations. Add distance to the mix, and groups of mangrove islands look like a contiguous shoreline. Coastal configurations lose their curves. Water, cloud and sky merge into distorted mirages. The horizon is lost: Boats appear to float in the air, birds seemingly fly underwater, and islands seem to shift imperceptibly. Now, throw in tidal variation.

When the tide is out, what should be a separate group of keys, according to a nautical chart, is connected by land. (The Everglades are shallow, averaging two to four feet, often less, and rarely deeper than six feet, with the exception of major tidal rivers.) *Channels, and the Wilderness Waterway-a 100-mile route that runs the north-south length of the park-are well marked by beacons. In some places, like Chokoloskee Pass, it is a matter of simply following the channel markers and boat traffic. In other places, like Hells Half Acre, tarot cards and a rabbit’s foot are needed in addition to a GPS, nautical charts, USGS quadrangle maps and a compass. Paddlers often start out on a marked trail, then branch off to unmarked routes. Overall, however, there are enough fixed positions such as campsites, channel markers and other signs to periodically confirm your position, without so many markers that the backcountry becomes a sign-posted highway in the watery wilderness.

When the tide is out, what should be a separate group of keys, according to a nautical chart, is connected by land. (The Everglades are shallow, averaging two to four feet, often less, and rarely deeper than six feet, with the exception of major tidal rivers.) *Channels, and the Wilderness Waterway-a 100-mile route that runs the north-south length of the park-are well marked by beacons. In some places, like Chokoloskee Pass, it is a matter of simply following the channel markers and boat traffic. In other places, like Hells Half Acre, tarot cards and a rabbit’s foot are needed in addition to a GPS, nautical charts, USGS quadrangle maps and a compass. Paddlers often start out on a marked trail, then branch off to unmarked routes. Overall, however, there are enough fixed positions such as campsites, channel markers and other signs to periodically confirm your position, without so many markers that the backcountry becomes a sign-posted highway in the watery wilderness.

Some of the biggest problems here are unseen and little. The unseen problem is wind. With great expanses of wide-open park waters, wind can be a problem. It is often windy: 1025 knots, on average. Small craft advisories are common in the Gulf. Paddlers often strike out early in the morning to avoid these winds, which generally kick up in the afternoon and die down around dusk.

These breezes can be your ally, as they clear insects-mosquitoes and no-see-ums (the little problems). The Calusa used a combination of fish oil and pine tar smeared on their bodies to keep the “swamp angels” at bay. Modern Everglades explorers should be prepared with insect repellent (both cream and spray), long pants and shirts, and a head net. In winter, the bugs can range from nonexistent to maddening. During summer, the bugs are so thick that they keep the backcountry essentially deserted. (Don’t come to the Everglades in summer!) There are few bug problems on the water, except occasionally along very narrow creeks.

December through March in South Florida is dry and pleasant, with highs averaging in the 70s and lows in the upper 50s. Precipitation runs under two inches per month. Be prepared for sunny conditions year-round with wide hats, sunglasses and sunscreen. Everglades paddlers must carry all their drinking water with them. A gallon per person per day is recommended.

Arriving at Tiger Key, I erected the tent by the flickering flames of a driftwood fire, backlit by a rising moon. Bill grilled hamburgers as the tide drifted out, extending our beach. It was a good thing we landed

around high tide. With a full moon and corresponding extreme tides, paddlers often have to drag their boats a long way to access the water. The ranger stations give out free tide charts that are very helpful in planning paddle times.

Early the next morning, a few no-see-ums nagged us as we loaded the kayaks and headed south on calm waters along the Pavilion Key Route. The expanse of the Gulf lay to our right and the labyrinth of islands to our left. As we paddled southeast along the edge of the keys, we decided to try our luck at trolling. I rigged my medium-weight rod with a Mirrolure, a minnow-like artificial lure, and fastened the rod under the deck bungies. It wasn’t long before the pole jerked, and I reeled in a two-pound sea trout-numerous in the Gulf.

When trolling, use lures that float. That way, if you have to stop, the lure won’t snag on the ocean bottom. Fishing is popular in the Everglades. In addition to fishing from a boat, I’ve had good luck surf fishing for snook, especially when I’ve used a Mirrolure on a rising tide. Snook, Jack Crevalle and mangrove snapper roam the rich, brackish waters that lie between the salty Gulf and the inland sheet of freshwater flowing toward the ocean. Sea trout and reds are common along the coast. Of course, angling areas often overlap. A valid Florida saltwater license is required. When obtaining your license, check the current size and creel limits.

Birding is a deservedly popular pastime here. Avian numbers aren’t nearly what they were when plume hunters depleted and threatened the bird population in the late 1800s. Subsequently, the Audubon Society established rangers in the ‘Glades to protect the birds, at the Society’s own expense. When a ranger was killed by plume hunters in 1907, a national outcry ensued, ultimately increasing protection for Southern Florida birds. Today, avian enthusiasts still have plenty to see, from roseate spoonbills-often mistaken for pink flamingos-to pelicans, eagles and osprey. If you wish to do birding here, be sure to bring binoculars and a field guide.

We stopped for lunch at Jewel Key, one of just a few islands with a rocky beach. A “rocky” beach here is defined as a few rocks mixed in with a lot of sand. Most beaches are sand beaches. While the beaches are kind to kayaks, underneath the water lies a different menace: oyster bars. These large clumps of shells with sharp edges will scrape a plastic kayak or glass boat and turn a folding kayak into a shredded boat. I do not recommend a folding kayak for the northern Everglades. Oyster bars are often found in island shallows. When walking here, wear shoes that cover your entire foot. Paddlers in the southern Flamingo area of the ‘Glades don’t face much of this hazard.

Beyond Jewel Key, we kept southeast. The turquoise waters of the open Gulf lay to our right, while a labyrinth of verdant islands shielded the mainland. The sun shone brightly overhead. Rabbit Key, a small island of a few acres, was our next stopping point. A couple of hours later, three miles from Jewel Key, we were paddling along the eastern shoreline of Rabbit Key. Paddling around a point of land, we turned and followed a narrow trail of water inland. It opened out into a broad, sandy lagoon-a protected backcountry campsite. Rabbit Key is within striking distance of Chokoloskee Island, the other jumping-off point for the Ten Thousand Islands. We stretched our legs, then returned to the boats, as the afternoon was passing quickly.

We then veered due south into wide-open, but shallow waters. The ocean was as smooth as polished marble. We passed Little Pavilion Key, just a smattering of sandbars. A century ago clammers lived here in huts perched on stilts over the water. These settlers harvested clams from the adjacent waters, finding them with their feet (which were wrapped in canvas to keep them from getting cut, yet allowing them to feel the clams). Storms, winds and the tides have obliterated any evidence of their time here. A short time later, we began the approach to Pavilion Key. With the tide out, we had to stroke far into the Gulf to access the island, in order to avoid extremely shallow water.

Pavilion Key is more than a mile long and a quarter-mile wide. The backcountry camping area, on the sandy northern tip of the isle, accommodates 20 campers per night. A long spit of land extends out from the forested part of Pavilion Key, catching ocean breezes. The long western shore is mostly sand, offering beachcombing opportunities.

Cool air blew in from the ocean as Bill and I settled down by the campfire and ate shish kebabs while we reflected on our 11-mile day. To the west, the sun descended into the Gulf of Mexico, painting the sky multiple hues, from yellow to orange to pink, then begrudgingly giving way to a slaty dusk smudged with high clouds. Within an hour, the moon was so bright we could explore the beach without flashlights. Then we heard a rustling by the boats.

Small dark shapes scurrying along the sand contrasted with the lighter beach. Raccoons! We raced after them, and they disappeared into the trees. They couldn’t get our food, however, since we had stored all of our food and water inside the hatched compartments of the kayaks. Pavilion Key and most other beaches have food-habituated raccoons that will get your food and tap into your water supply. Store your food and water inside your kayaks, as the masked marauders have been known to cut into each and every jug of agua, effectively ending a trip.

A continuous popping of the tent fly awoke me the next morning: wind-strong wind. A front had blown in on us sometime in the night. After a cup of hot coffee and a quick walk on the beach, the two of us paddled into the early morning sun with a brisk wind at our backs. We skirted Dog Key, then entered wide-open rolling water from Pavilion Key to Mormon Key. This area of the coastline turns from southeast to south. The big turn is known as Chatham Bend. More mishaps have occurred in the four-mile stretch between Mormon Key and Pavilion Key than in any other waters in the Park, according to park rangers. Most Gulf incidents have occurred when canoeists have tried to paddle the open Gulf during smallcraft advisories. They paddle out to Pavilion Key, where they get trapped by high winds. When they make an ill-fated break for the coast, they end up getting swamped.

Sea kayakers fare far better in the Gulf. Current paddler use in the Park is split roughly in half between canoeists and sea kayakers, but the rise in sea kayaking over the past decade has been phenomenal. A decade ago, less than ten percent of backcountry visits were by kayak. Sit-on-top kayaks have increased in popularity in the last few years, as well. However, it can be cold in the ‘Glades, and I would rather be inside a boat when a cold front blows in from the north, kicking up winds and dropping temperatures into the fifties and below.

We cut through the murky waves, and safely made Mormon Key. Gulf waters are normally clear over a mud and/or sand bottom, but excessive winds can turn the Gulf into chocolate milk. In Florida Bay, in the southern Everglades, the clear azure waters are much like those of Key West and the lower keys. In the interior ‘Glades, away from the Gulf, the water is clear, with a few exceptions like often-murky Broad Creek.

It was very windy as we set up camp, so we were grounded for the time. I set out to explore the key while Bill rested beneath a tarp, nursing a sore back. As I walked along the sand beach to the south, I watched the waves beat the shoreline. A scattering of broken conch shells in pastel tones of ivory and pink lay at the high-tide line. These were remnants of the Calusa: They discarded the conch shells after harvesting the delicate morsels inside. Farther around the island, broken slabs of concrete extended away from the island: remains of a dock that belonged to a settler who lived here with both his first and second wives in the early 1900s. Locals then dubbed the island “Mormon Key.” The Everglades are loaded with other interesting names that lead one to ponder their origin, including Jack Daniels Key, Demijohn Key, Gun Rock Point, Topsy Key, Lostmans Five, Snake Bight, Darwins Place and many more.

We arose the next morning to gentle waves lapping at the beach and a slanting sun promising a warm day. I started the coffee and Bill began breaking camp. We quickly loaded the boats to take advantage of the smooth water. The placid ocean made for easy paddling as we left the Gulf on the Chatham River Route and headed to the “inside,” up the Chatham River. The tide was in our favor, and after three miles of paddling, we found ourselves at Watson’s Place campsite. Watson’s Place is a 35-acre shell mound that was once the farm of the notorious Ed Watson. He had the nasty habit of hiring workers for his sugar cane, banana and vegetable farm and killing them after they had worked for him, rather than paying them. Word of Watson’s deeds spread among the locals and, in 1910, upon landing at Chokoloskee Island, Watson was gunned down by a posse. Most of Watson’s victims were never found. It is rumored that the ghosts of the slain roam the homesite.

We pulled up to the wooden campsite dock and tied up the boats. A large black kettle circled by bricks and a low, square cistern lay to the left of the dock. Everglades settlers obtained fresh water by collecting roof runoff, then running pipes to cisterns for storage. The kettle was once used to boil sugar cane “juice” into syrup. Tall gumbo-limbo trees that once shaded the homestead backed the clearing. Gumbo-limbo trees are sometimes called the “tourist tree,” since they have a distinctive peeling red bark under a spreading leaf crown.

After stretching our legs at this unfortunate site, we climbed back into the kayaks and continued up the Chatham River. A short time later, we intersected the Wilderness Waterway. The mangrove-lined river is around 100 feet wide here, in contrast with the open Gulf. While strong tides can effectively block passage around the mouths of rivers at the Gulf, the effect is more moderate farther inland. Here, seven miles inland, while the tide had turned against us, there was minimal tidal influence. The shadows and rich colors of the dense green foliage indicated that it was late afternoon.

We stopped paddling to take a look at the nautical chart. Comparing the chart to the shape of the low mangrove shoreline around us, we found the slender mouth of Sweetwater Creek. The stream was tranquil in comparison to the raucous waves of the Gulf the day before. As its name implies, tasty fresh water flows out of the ‘Glades in the upper reaches of this creek. Only a few birds broke the wilderness silence while we paddled up Sweetwater Creek. The lush foliage closed in until the stream was only 40 feet wide. It felt as though we were very far off the beaten path.

Two miles from the Wilderness Waterway, after a half hour of paddling, we arrived at the Sweetwater chickee. This was a “double” chickee, with two camping platforms attached by a central gangway and a vault toilet. A couple of fellow paddlers had already set up their tent on one side of the chickee. After setting up camp, we exchanged paddling tales with our neighbors. They had flown down from New York and were paddling folding kayaks. I warned them to be careful of the oyster beds they were sure to encounter in the Gulf.

The still air allowed the temperature to fall into the mid-fifties overnight. The dew was heavy on our boats the next morning, and my tent was so wet that it looked like there had been a rainstorm during the night, but there hadn’t been: Heavy dew is common in the Everglades. After we had breakfast and packed up the boats, Bill and I left the Sweetwater chickee and backtracked down the creek to return to the Wilderness Waterway. The morning sun was at our backs as we paddled northwest on the Last Huston Bay Route. Park service signs made our course fairly easy to follow, as we paddled past a series of shallow bays. Dense mangroves lined the bays, many of which were bisected by small creeks. While tidal influence is minimal here, some of these bays are large, and can kick up some big waves of their own.

By mid-afternoon we had paddled nine miles, and arrived at the Sunday Bay chickee, another double chickee. After setting up camp, I explored the creeks northeast of Sunday Bay while Bill fished. Returning to camp, I found that Bill had caught and released a couple of Jack Crevalle, known more for their fighting prowess than their edibility. Later, as we relaxed after dinner, a gentle night breeze tapped the boats against the chickee. I thought about those who live in northern states, facing the ravages of winter, while I lounged in shorts.

Arising at dawn, we put the boats in the water, climbed in, and shoved off. It was the last day of our trip. At the west end of Sunday Bay, we paddled out of the Wilderness Waterway, then headed west on the Hurddles Creek Route through the ultra-shallow Cross Bays. Within an hour, Bill and I came to Hurddles Creek, a small creek that was bordered by extremely thick stands of mangrove. A short time later, the creek opened into Mud Bay, which was less than a foot deep in many places. The last mile of Hurddles Creek went quickly, then we arrived at the Turner River.

This river is named for the guide who, in 1857, led the U.S. Army up the river as they attempted to drive Seminole Indians from the Everglades, in an effort to drive them out of Florida. The army paddled up the Turner, then marched through the interior swamps to destroy some Seminole villages. When the expedition’s leader was killed in an ambush, it brought an end to the Third Seminole War. The remaining Seminoles formed the nucleus of the Southern Florida tribes currently located on reservations in the Everglades.

As we paddled downstream, we passed a nearly vertical Calusa shell mound that reached 19 feet in height-lofty, by Everglades standards. I tried to imagine the generations of families gathering and consuming the shellfish to make such an enormous mound. Bill led the way into Chokoloskee Bay, and we paddled the final three miles on the Causeway Route. The busy bay made for a fitting reintegration into the “real” world. The past five days were packed with memories, from dolphins to the world’s best sunsets, to delicious, fresh-caught sea trout, to the eeriness of Watson’s Place.

I still had miles to paddle before completing the book, however, I looked forward to slipping back into my kayak to create more memories, for, as Marjory Stoneman Douglas put it in the opening sentence of her book, “There are no other Everglades in the world.” And there is no other experience in the world like paddling the Everglades.