Kayak spray decks make lousy chart tables. They are small, wet and flexible. Let go of a tool or chart and it’s overboard; roll and everything is soaked. Most tools, like parallel rulers and dividers, are designed for warm, dry navigation stations. Fortunately, there are tools that work well with a spray-deck navigation station, but you won’t find them mentioned in the average navigation book or at your local navigation course.

Tools that work aboard a kayak have to be small, durable, and at least water resistant, if not waterproof. You may want to make some yourself, and even those available commercially may need or benefit from modification. These tools are the ones that we show students in courses on the Maine coast, where fog, big tides and rocks make navigation especially interesting. Trips start with charts. Government charts are printed on paper and, when they get wet-which they will-they have to be dried carefully or they become costly mush. Waterproofing them goes a long way toward helping them survive immersion and mildew. The old waterproofing mixes were pretty volatile, and they needed ventilation or you lost brain cells, but the new waterproofing mixes are water-based and easy to use. All you need is sponge brushes and a piece of clean plywood to spread the charts out on. Charts need to be folded to be usable on deck. When you fold them, the section that you are using may lack important things like the compass rose and the scale. So, before you waterproof your chart, it’s a good idea to look at it carefully and see where you might want to add another compass rose.

You can get a bunch of self-adhesive compass roses in a package. Some care is needed to make sure that you line up the rose so that north is in line with magnetic north, and so you don’t obscure key navigational information. I usually trim the roses to get rid of extraneous printing that would obscure things on the chart that I need to see. The numbers are pretty small for aging eyes, so I mark the cardinal points with a green waterproof fine-tipped marker. I favor green, as it will show up if I’m using a red light at night to preserve my night vision. Before waterproofing, you may want to consider whether you would like to write any useful notes on the chart. And you might want to add a scale or two. While all this can be done after the chart has been treated, items you affix to the map will stick better before the application of waterproofing. Let the waterproof marker dry well before treating the chart, and don’t rub any of the marks before the waterproofing dries. You could also, of course, use a pencil or a ballpoint pen, but they may not be as legible as a waterproof marker against the chart’s printing.

Charts need to stay attached to the boat, and they are best secured by putting them in a transparent case.

Several companies produce waterproof chart cases. They work pretty well if you are careful when closing the seal. However, it’s a good idea to waterproof your charts even if you use cases, since water creeps in, even if only as condensation. If the chart case doesn’t have clips, you will need some; don’t depend on your deck bungies to hold the case securely on deck. Your local marine hardware dealer will have a selection of small stainless-steel carabiners or snap hooks. The smallest has a waist at one end so that it can go on a D-ring, then be lashed into place. I like the sailing carabiners so well that I have them on all deck and cockpit gear. Their extra cost is worth it. The smaller the chart case, the more times you need to fold the chart, so I usually go for the biggest chart case that will fit on deck without hanging over the side. The cases that are about 16″ by 22″ allow a NOAA chart to be folded into quarters if you trim the vertical margin off to just the latitude line.

The new plastic charts keep you from having to waterproof paper. They are a bit more expensive than NOAA charts, but they cover more area and have a second chart on the back. Compass roses will stick to these plastic charts and waterproof markers will work if you let the ink dry carefully. These charts are very durable; one that I use all the time finally died after two seasons of being unceremoniously stuffed under the bungies on my foredeck. While they sort-of stick themselves to the deck when they get wet, it’s still best to put them in a chart case to keep them from getting damaged or lost. For special navigation situations, I often carry topographic maps for the area, in addition to the navigational chart. The advantage is that they have a scale of 1:25,000, which provides better shoreline detail. While they indicate depths, their disadvantage is that there is no navigational information printed on them. Of course, you can write them on the chart, but it is a lot of work.

Be sure to waterproof any topographic maps as well. Recently, I have taken to using charts and maps on CD-ROM. The water-proof, integrated kayak computer nav station is still in the future, so I print charts at home. It is convenient, as they are single sheets, and one is usually all you need for a short paddle.Or you can make up a set of custom 8 x 10 charts that you can use as a trip book. Ink-jet ink will smear when treated with waterproofing solution, but there is a waterproof ink-jet paper that works well. The nice thing about printing your own charts is that you can make one for each person in the group, and you can scale it to the level of detail you want. Make sure that you include a scale of miles on the print-out. If you use a GPS, you can print tracks and data from a GPS receiver on these, and you can use the computer to make it easy to load the GPS with waypoints. A computer with the appropriate navigation software makes it much easier to determine waypoints for the logbook and GPS while you are planning your trip. Even if you don’t invest in the full CD-ROM charts, most GPS manufacturers provide simple data-entry software that comes with a GPS-to-PC cord. Tide-and-current tables should be kept at hand in your chart case. Rather than keep the whole tide book in the chart case, I make photocopies of the appropriate tide table and the page of corrections for the region. Fortunately, photocopies can be waterproofed. In some areas, you may find the year’s tide tables printed in small, waterproof booklets. They are ideal for carrying on deck if you have young eyes. For my old eyes, the type is too small to read, so I find it useful to keep a simple plastic magnifier in my chart case. It’s nothing more than Fresnel lines inscribed on a piece of plastic. The one I use is designed for navigation and has a scale on one side. You can find one of these in a marine supply store. I keep a compact backpacker’s compass in my PFD pocket. For taking bearings, it is easier to use a backpacker’s compass than to maneuver the boat to use a deck-mounted compass. This hand-held compass is also handy for checking the deck-mounted compass, in case I’ve put the radio or a propane cylinder too close to it, making it inaccurate. It is also there as a backup and for use on land, whether you take a hike or want to take bearings from the beach. Besides charts, you need tools to measure bearing and distance. People talk about kayak navigation as an art, not a science so, to be artful, try using your hands as tools. Try various finger joints, finger extensions, finger widths and hand spans against the scale of your charts. You will likely find something that is close to a mile, and something that’s close to five miles. For example, on a 1:40,000 chart, my hand span is about five miles; the distance from the tip of my thumb to the first knuckle is a mile; and the distance between my index finger and little finger when held out straight is two miles. With practice, you can use the side of your forefinger or the back of your hand to transfer bearings between the compass rose and a particular spot on the chart. Keep your wrist locked straight and use your shoulder muscles to move your hand. Move your hand from the compass rose to the bearing that you want, or from the bearing line to the compass rose. You will be surprised how easy it is to hold the angle you need, within five degrees or so.

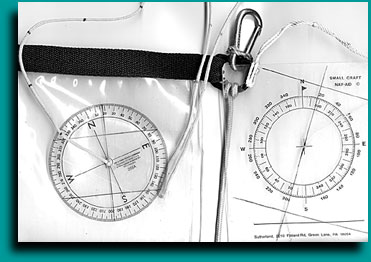

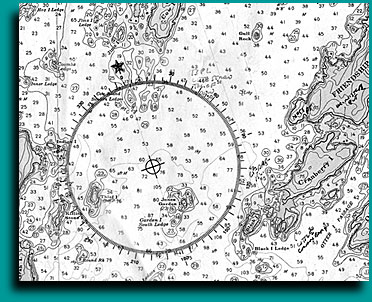

It might not be up to Coast Guard or Power Squadron standards, but you’ll always have the tools. Most of the standard devices for figuring distance/direction on a chart are too complex for use on the deck of a kayak. The exception is the Small Craft Nav-Aid developed by Chuck Sutherland specifically for kayaking. It is a 4″ x 5″ piece of clear plastic with a compass rose and reciprocal rose on it. A piece of monofilament is fastened to a hole in the center. The user marks the plastic, using a waterproof marker, with lines that show true north-south and east-west directions, according to the variation of their local region. When these lines are lined up with latitude or longitude lines, the rose points to magnetic north, and the monofilament can be stretched out along a course, or bearing line. Bearings and back bearings can be read directly. The monofilament can be marked according to the chart’s scale, so that distance can be read directly along the mono-filament. If you attach a light string lanyard that you mark with miles, the string is easy to place along a convoluted route to estimate paddling distance. I usually carry a spare Nav-Aid, since mine, over time, have faded, been broken or had the monofilaments pulled out. If the monofilament pulls out, the center hole can be enlarged slightly and another light string substituted. You can make a device similar to the Nav-Aid from a one-armed protractor commonly found in a marine supply store.

The small C-Thru (# 255A) is especially handy for this do-it-yourself project. These come in two sizes: 7″ in diameter and 3.5″. First, cut the movable protractor arm off. (Save the cut-off arms, as these are usually marked with scales, and are useful additions to your chart bag.) I leave a small tab on the remaining part of the protractor so I can punch a hole in it for a lanyard. Thread a thin, colorful piece of braided cord through the hole in the center of the protractor and knot the end. I like to knot it on both sides of the hole. Mark the protractor with true north for the chart you’ll be using.

For paddlers who are on long trips, or who paddle in different parts of the country, marking a rose with true north may be impractical. The Nav-Aid can be marked with two or three north-south, east-west lines using different colors, but the multiple lines can get confusing. There is a double rose on the market by Weems and Plath called the “Compute-a-Course.” The bottom part has a grid with a true north rose on it, and the top rose is magnetic. You line up the magnetic rose with the appropriate variation on the true north rose, and you are ready to go. The Compute-a-Course also has a pivoting arrow, but it is easier to use a mile-marked string through the center hole. You don’t really need the rose on the lower plastic card; all you need is the grid to align the device on the chart. For any of these protractors, a fast way of getting and reading reciprocals for back bearings is to turn the rose 180 degrees so that it is upside down. For trip planning at a campsite, you may want more accurate tools, or at least ones that let you draw lines. Again, parallel rules and other such devices don’t work well in small spaces, and are hard to carry. I favor two 90-degree triangles that are small and flat enough to go into your chart case. A few minutes of practice with them and you’ll see how easy it is to move bearing lines between a compass rose and a course. Just align one of the short sides of the triangle on the course and slide the two triangles along their hypotenuses. The triangles don’t slide as easily as parallel rulers do, but they are just as accurate. These will work on the bottom of a turned-over kayak or on a cutting board-any small, flat surface. I even used them to take the test for my Coast Guard license. These simple navigation tools can be used in combination with a GPS receiver. Waterproof GPS units are becoming more affordable. Get a waterproof bag for your GPS for additional security, and for flotation if you drop it. Most GPS units will drain batteries in about twelve hours, so you will need to turn it on, acquire the needed information, then turn it off. Be sure to carry spare batteries.

When you first get a GPS, take the time to learn its various functions. After you read the manual, get a book on using a GPS, or take a course. Don’t depend on a GPS alone; you still need a boat compass to steer, as the screen is small and hard to read unless you hold it very close. The biggest challenge in GPS use is translating the position indicated in the unit to the chart. You don’t want to be plotting latitudes and longitudes while you’re sitting in the cockpit. Instead, if you pre-load the centers of the various compass roses on your chart as waypoints, the GPS can give you your bearing and distance from the compass-rose waypoint, so all you need is the scaled piece of string to find your position. Alternatively, call up a waypoint that you have loaded in the GPS and marked on your chart, and use your Nav-Aid or string-equipped protractor to measure bearing and distance from the waypoint. You may find pre-printed waypoints on commercially printed charts. Since the navigators of many larger boats use these waypoints to set their autopilots, the traffic around these points can be high. These waypoints are good things to use to establish your position, but they are bad places to be near at night or in fog. GPS units require that you name your waypoints. Since the GPS can use only a limited number of letters for a name, I often have trouble remembering what name I’ve assigned to a waypoint. I use a 3″ x 5″ waterproof notebook to record the names of all of my waypoints, and for other useful navigational data that I might want to have with me in the field. I write down things that are hard to remember, like line-of-sight distances for various eye heights, rules of thumb, formulae and the like. If you aren’t using these navigational numbers all of the time, they’re easy to forget. In addition to the waterproof notebook, you can use a soft pencil or a grease pencil to write things down on the deck of your boat or on something similar to the white plastic note boards made for sea kayakers or scuba divers. You probably have your own pet tools for kayak navigation-these are some of mine. My criteria: small size-nothing that can’t fit into a chart case; low cost-you will probably break or lose things; and, above all, that they work in the small, wet space of the kayak foredeck.