“Maybe this isn’t such a good idea,” I thought nervously as I wedged my paddle between two ottoman–sized icebergs. They were translucent–blue and among the smallest bergs jammed against my kayak–the largest was toward the bow and was more sofa-sized, to complete the living-room set.

Ice and fiberglass scraped together as I drove my paddle between the bergs and rocked my boat from side to side, loosening the ice at my bow. Ahead, dense ice concealed the water for a half-mile, and behind me, more ice had engulfed an opening I’d used only 10 minutes earlier. But that wasn’t my main concern; I’d pushed through dense ice before.

The big deal was the 200-foot-tall glacier about a quarter mile to my right–an uneven wall of blue and white ice about a mile long. For about a minute, ice had been falling from both sides of one of its giant pillars, smacking the water with reports like gunfire. The pillar–weighing thousands of tons–leaned precariously over the water.

“It’s not so dense about a hundred yards to your left–if you can get there,” radioed my co-worker Malinda Lueck. She was a half-mile away at the edge of a cliff 350 feet above the water. I could barely see her small figure against a fjord wall that rose thousands of feet into soggy clouds.

Just then, I heard a sharp crack. Turning quickly toward the glacier, I saw the skyscraper-sized pillar topple into the sea, sending an explosion of water and ice 150 feet into the air. The roar was terrifying as icebergs and 15-foot waves crashed against the granite shore bordering the glacier. Seconds later, another top-to-bottom section collapsed, echoing like a bomb blast against the surrounding mountains.

I could only watch as the waves approached, giant wrinkles in icy water, and soon I was rising and falling eight feet, with bergs grinding against my boat. The entire mile-long fjord was alive with rolling waves and the sound of crackling icebergs.

All in a Day’s Work

I am a kayak ranger. More accurately, I am a U.S. Forest Service wilderness ranger who happens to travel by sea kayak. I work in the Tongass National Forest, in one of southeast Alaska’s most spectacular wilderness areas, where high mountains covered in ice and snow rise directly from the sea, and three enormous glaciers flow to the ocean from the Canadian border. In southeast Alaska’s intimate blending of land and sea, I commonly encounter bears, mink, otter, humpbacks and orca while on the job.

But those are just perks of the workplace. The actual job is monitoring and protecting parts of the national forest that are designated wilderness: lands managed to retain their pristine condition. Along with four other rangers, I work full-time for six months each year. For most of the season, we patrol the wilderness by sea kayak for nine-day stints–enough time to travel parts of the area’s extensive shoreline and contact widely dispersed visitors. After nine days, we spend one day at the office writing reports and maintaining gear, then take four days off to recuperate before the next outing.

The Forest Service supports three kayak ranger crews in Alaska, with between two and six employees in each crew. They are the agency’s eyes and ears in Misty Fiords National Monument near Ketchikan, the Tracy Arm-Fords Terror Wilderness near Juneau, and the Nellie Juan-College Fjord Wilderness Study Area in Prince William Sound.

But before you request an application, you should know that parts of southeast Alaska receive more than 200 inches of rain annually and that the mean temperature in July is a hypothermia-inducing 56°F. The ocean temperature is somewhere in the low 40s and much colder near the glaciers. Then consider the steep and rocky shores–difficult places to land a fully loaded sea kayak, particularly in pouring rain–and the nearly impenetrable rain forest that borders the sea. The conditions are inhospitable, to say the least.

“I prepare for the season by whacking myself on the forehead with a two-by-four for 30 minutes each morning,” says Kevin Hood, a wild-haired Californian of 33 with a boyish enthusiasm for the outdoors. “Then,” he continued, “I take a freezing-cold shower with all my clothes on. Still, I never feel prepared.”

Photo:Forest Service ranger Ethan Kelley relaxes in light mist after a long day. Copyright Tim Lydon

Kayak rangers tend to move from one project to another. Like most wilderness rangers, our crew is involved in a variety of projects that help us manage and understand our area, provide education and assist with research.

For instance, Misty Fiords kayak rangers coordinate with botanists and biologists to survey flora and fauna and find rare species, creating a snapshot of southeast Alaska’s plant and wildlife communities. In Prince William Sound, kayak rangers have worked with the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) and Alaska Pacific University to better understand the impact visitors have on popular campsites, which will guide management decisions.

So what was I doing stuck in the ice?

Prior to my run-in with the collapsing ice pillar, I had spent three days with two rangers camped a quarter-mile from a tidewater glacier in Tracy Arm, where we gathered data on harbor seals for the state wildlife agency and the University of Alaska Southeast. The data, including population counts and behavior trends, established baseline population estimates and may help explain the recent and sharp decline of seals in parts of Alaska.

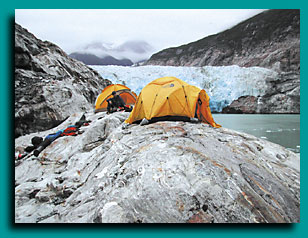

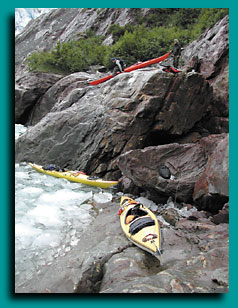

As I’d learned long ago, nothing is as simple as it sounds with this job. First, just arriving at “seal camp” was challenging. After kayaking 30 miles of narrow fjord–usually two eight-hour days including breaking and setting camp each day–we had to push through thick ice to a rocky bluff a quarter-mile from the glacier. Between calvings, which sent big waves crashing against the bluff, we landed our boats and carried our gear 40 feet up slippery crags to a lumpy ledge barely suitable for camping.

Making camp–tying boats to boulders, setting tents, bear-proofing our food by hanging it from a cliff–consumed several hours, then we had to establish our research station, about 350 feet up the 5,000-foot mountain looming above camp.

In light rain, we carried dry bags full of tarps, binoculars, spotting scopes, tripods and data forms up a series of steep cliffs covered in dense brush. At one point, we crossed an avalanche deposition from the past winter, strewn with the torn fur and mashed bones of an unlucky goat that had perished in one of the slides.

At 350 feet, we reached an exposed ledge with a view straight down at the fjord, a mile-wide body of green ocean covered in icebergs ranging in size from hockey pucks to houses. In spring, more than a thousand seals congregate on the bergs to give birth to their pups. From 350 feet, they looked dark and sausage-shaped, but powerful binoculars provided close-up views without disturbing them.

In the following days, we settled into a routine: After breakfast on the bluffs by camp, we hiked to the research station by 8A.M. and began hours of seal counts and observations. Although a glacial wind blowing cold showers made huddling under a tarp uncomfortable, southeast Alaska’s dynamic nature provided endless entertainment–the glacier released enormous calvings, occasional avalanches roared down nearby mountains and bald eagles flew low sorties over the ice pack looking for afterbirth or stillborn seal pups. Between 10 A.M. and 2 P.M. each day, up to 20 tour and pleasure boats entered the icy bay for a view of the glacier.

Each afternoon, we hiked back to camp and cooked dinner close to the water.  Steep cliffs prevented much hiking, so afterdinner, we watched the glacier, read or retreated to the tents if it rained.

Steep cliffs prevented much hiking, so afterdinner, we watched the glacier, read or retreated to the tents if it rained.

Sleep was fitful at best. Darkness didn’t arrive until after 11 P.M., the glacier calved loudly all night, and the arrival of light at 3:00 in the morning aroused a chorus of songbirds right outside the tents.

Although the setting was spectacular, I was glad to leave seal camp on the fourth day for tamer surroundings and possibly some better sleep. Our other two rangers needed help removing an abandoned boat from a beach 30 miles away, so the next morning, I lowered my kayak down the bluffs, quickly loaded my gear, then launched on the frigid water.

Navigating Alaska’s Shores

The Forest Service uses kayaks for a couple of reasons. First, they facilitate access to Alaska’s relentlessly steep shores, enabling rangers to land in nooks too steep and narrow even for skiffs. And kayaks can be hauled out of the water at night, whereas skiffs have to be anchored, often an impossibility in fjords hundreds of feet deep and filled with drifting ice.

“Another advantage of working from kayaks is that we blend in with the wilderness we manage,” says Malinda, who has been with the program for three years. “We can visit campers and observe wildlife without disrupting them.”

While non-motorized travel is consistent with wilderness management objectives, it can be dangerous in Alaska’s harsh elements, and the Forest Service holds its employees to the highest safety standards. For instance, in Juneau each ranger is trained in a variety of self- and assisted-rescue techniques, first in pools, then in Alaska’s frigid waters. While on the job, they are required to carry a marine radio, paddle float, bilge pump, spare paddle, towing system and PFDs equipped with survival kits that include flares, strobes, space blankets, knives and magnesium strikers.

However, immersion suits are not required. Rangers go ashore frequently to inventory impacts, talk to campers and conduct other duties, and in the region’s constantly changing weather, such suits would be impractical. Instead, rangers always travel in pairs and are required to make radio contact with a dispatch office every 30 minutes while away from shore. Some programs even require carrying EPIRBs (emergency position-indicating radio beacons).

The downside to kayaks, of course, is that they are slow, especially against Alaska’s powerful tides, weather and ice. So occasionally we do use skiffs. But with tour boats frequently visiting the area, kayak rangers near Juneau and Ketchikan have established a barter system with the tour operators and share their knowledge and experience in exchange for quick transportation.

For instance, the morning I got stuck in the ice, I had an appointment with the MV Sea Lion, a 70-passenger vessel providing weeklong tours of southeast Alaska. As the waves from the calvings subsided, I found they had loosened the ice near my kayak, enabling me to paddle a mile through sporadic bergs to where the boat had stopped at the edge of another thick ice pack.

enabling me to paddle a mile through sporadic bergs to where the boat had stopped at the edge of another thick ice pack.

Forty passengers in raincoats braved the drizzle and cold breeze on the boat’s bow, cameras ready for the next calving. But as I approached, steering around icebergs many times my size, they turned their attention to me.

Photo: Phil Dewitt, a kayak ranger in Tracy Arm-Fords Terror Wilderness near Juneau, boards the tour boat Sea Lion. Onboard, Phil will share his knowledge of the area with visitors to southeast Alaska. Copyright Tim Lydon

“Aren’t you cold?” one of the passengers called from the top deck, 40 feet above.“Where did you come from?” yelled another.

We visit about 40 tour boats each summer, and the passengers usually react with the same surprise.

I paddled to the boat’s stern, where the crew lowered a ladder and helped me aboard. After helping pull my kayak onto the rear deck, they led me inside and offered me hot chocolate.

Before greeting the passengers, I hung my soaked rain gear near the ship’s galley and pulled my Forest Service shirt and hat from a dry bag I’d carried aboard. Although we usually wear sturdy rain gear, wool hats and synthetic layers while on the water, we carry clean uniform shirts for our more formal duties. In minutes, I had transformed from dripping kayaker to uniformed ranger.

A Captivated Audience

Education is an essential part of wilderness ranger projects and usually addresses minimizing physical and social impacts. However, the volume of tour boat passengers, Alaska’s spectacular scenery, and the fact that its two national forests are the nation’s largest provide kayak rangers a unique opportunity to educate on a broad range of topics.

Shortly after I boarded the Sea Lion, the vessel began its 30-mile sailing back to Stephens Passage, where it would leave our wilderness for its next destination. The trip would take three hours, and along the way, we would pass between high mountains and hanging glaciers.

For the first half-hour, passengers gathered in the lower lounge where I provided a talk about the Tongass, wilderness management and our specific projects. Afterward, I answered questions on a wide array of topics, including past and present cultures, natural history, logging and mining on the Tongass and specific wilderness issues.

These wide-ranging discussions provide rare communication between the Forest Service and boat-based visitors to the Tongass, making the program popular with both the public and the agency.

But the exchange also creates mutually beneficial dialogue between the Forest Service and tour operators. The topic of seals provides a good example: Ship naturalists receive current and accurate information about seals from rangers who help study them, and rangers have an opportunity to educate boat operators on low-impact ways of observing seals.

Between visiting boats, rangers also visit campers to share their Leave No Trace (LNT) expertise and information about the area. And in Whittier, Alaska, at the edge of Prince William Sound, rangers maintain an education yurt where kayakers and other boaters headed for the Nellie Juan-College Fjord area can find LNT, safety and logistical information. All three kayak ranger crews provide education in local communities by speaking to outdoor groups about LNT camping and wilderness management and helping train naturalists and kayak guides who bring visitors into the wilderness.

After three hours, the Sea Lion powered down to drop me off in a large bay surrounded by mature rain forest and glaciated peaks that mark the wilderness boundary. A few dozen passengers leaned over the rails as I descended the ladder and settled into my kayak. They waved and took pictures as I backed away, turned with a broad sweep stroke and paddled south.

Ten minutes later, I landed on a small island with lush rainforest growing right to its edges, the location of our primitive base camp. My co-workers Kevin and Jenny had arrived a few hours earlier, after paddling six miles from their last camp, and helped me carry my boat from the water.

“Dude!” exclaimed Kevin as we pulled lunches from our dry bags, “We were five feet from a humpback whale! It made a beeline toward us from a half-mile, then swam under our boats.”

“Wow,” I responded. “I’d say that’s the record, Kevin. Congratulations!”

It’s not uncommon to see humpbacks during our travels, and they occasionally  get pretty close.

get pretty close.

After lunch on the beach, we loaded rope, Pulaskis (axes with a hoe-like digging tool opposite the blade) and trash bags into our boats, then began a four-mile crossing to the mainland, where we would break apart an abandoned fiberglass skiff. Weather permitting, a barge would arrive the next day to haul the debris away.

Photo: Lonely Lookout: Shielded from the rain by a tarp, rangers spend a cool morning counting seals in one of southeast Alaska’s glacial fjords. copyright Tim Lydon

Like much of southeast Alaska’s Inside Passage, steep hills surround the bay, keeping its water flat and calm. Humpbacks sounded in the distance as we paddled, and the low clouds common to the region broke apart and clung to the mainland, creating fractured views of ocean, glaciers, forest and rocky peaks.

Ninety minutes later, we arrived on a small beach overhung by green forest and dragged our boats over wet sand dotted with mink and bear tracks. At the head of the beach, a winter storm had driven the abandoned boat halfway into the forest. Our job was to break it into manageable pieces with our Pulaskis, then drag it closer to the water where the barge could winch it aboard.

“We’re glorified janitors,” a former co-worker used to say of rangers.

While education and research are more stimulating, removing garbage is an equally important part of our job. But it’s not always fun. We’ve had to remove plenty of soiled toilet paper from stream sides to protect fresh water sources, and we commonly pack out food scraps so bears don’t become accustomed to human food. We also find clothing, broken equipment and food wrappers and break apart fire rings in an effort to maintain unspoiled beaches for wildlife and campers.

We spent two hours demolishing the boat and filling garbage bags with debris, then set up our camp just above the high tide line. After a big dinner of pasta with pesto, artichokes and Greek olives, we watched sea lions feed in a nearby kelp bed. As night slowly fell, wolves howled from the mountains behind our camp.

The next morning, Kevin and Jenny would wait for the barge, then paddle 10 miles to visit a group of kayakers on a commercial tour of the area. My next assignment was a four-mile paddle toward the bay at Stephens Passage, where I’d catch a ride back to Juneau on another tour boat. That night, I would be relieved to be back in town, where eating out, sleeping indoors and listening to music would be welcome novelties.

We spend five days in town after each trip. The first day is spent in the office writing reports, drying equipment and finalizing plans for the next trip, then we take a four-day weekend to enjoy civilization’s comforts. But as enjoyable as it is to sleep indoors and wear dry clothes, by the fifth day, we are usually itching to return to the field for the next trip. The work is always interesting and challenging, and the eagles, whales and tapping rain provide an unbeatable soundtrack to the workday.

Alaska’s Kayak Rangers: How to Apply

Applying for seasonal work with the Forest Service can be daunting at first, because of the lengthy application forms. However, determined applicants have an opportunity for rewarding jobs on some of the nation’s most spectacular public lands.

Each winter, often as early as January, the Forest Service begins recruiting for thousands of summer positions across the country, including wilderness rangers, trail laborers and biological assistants. To simplify the process, the agency has centralized advertisement of these positions through an Online application process. You can find available positions and a summary of the application process at the Forest Service web page: www.fs.fed.us

However, specific positions are sometimes not described in detail on the website. Applicants can learn more about specific jobs by contacting Forest Service district offices in areas where they are interested in working.

For instance, contacting the Juneau Ranger District (907-586-8800), the Ketchikan-Misty Fiords District (907-225-2148) or the Glacier Ranger District (907-783-3242) is a good way to learn about the availability of Alaskan kayak ranger positions. By January of each year, program managers usually have an idea of how many new employees are needed for the summer.

Of course, competition is high for kayak ranger positions. But it often surprises applicants that kayak mastery is not highest on the list of qualifications. While kayaking and other outdoor skills are important, a passion for designated wilderness, public-speaking skills, and the desire to educate wide-ranging wilderness visitors are essential. And flexibility is essential. Rangers work in primitive conditions and challenging weather and are often paired with only one other person; patience and strong interpersonal skills are among the strongest assets an applicant can offer. The Forest Service’s thorough kayak training can prepare less-experienced paddlers for the job, but the other skills are often talents no training can provide.