Since taking up residence in Apalachicola, a sleepy town of about 2,500 located 70 miles south of Tallahassee, I’ve read a boat-load of books and articles on this historic and enchanted coast where it’s a 100-mile drive between stop lights.

But nobody describes it better than photojournalist Richard Bickel in his book, The Last Great Bay: “Here, where the sweet waters of the Apalachicola River mix with the salt of the Gulf of Mexico behind a broken screen of barrier islands, a great cradle of life has evolved into one of the most remarkable ecosystems in North America, with the highest density of reptiles (including alligators) and sea life north of Mexico, many of whom are endangered. The Apalachicola drainage basin, and its cosmos of streams, bays, tidal creeks and marshes, act as breeding ground and nursery for thousands of animals that thrive in this ideal mix of fresh and salt water. To understand the vitality of these waters, witness the renowned Apalachicola Bay oyster. Reaching market size in as little as seven months—versus up to two years for its Chesapeake cousin—the robust bivalve is symbolic of the Bay’s life forces.”

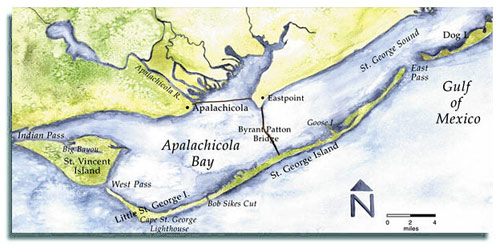

Symbolic it may be, but on today’s fall excursion with my wife, Peggy, I’m muttering curses at the mollusk. An ebb tide has marooned us in a tangled maze of oyster beds as we paddle the bay to St. Vincent Island, the largest of the four barrier islands—including St. George, Little St. George and Dog—that separate Apalachicola Bay from the Gulf of Mexico. Extensive oyster beds, some of which are completely exposed at low tide, dot the bay in clumps of razor-sharp shells. (Warning: Always wear sturdy foot gear while kayaking these waters.)

An oysterman afloat in deeper water in his flat-bottom skiff looks on with apparent disdain as I carefully stand up in the kayak to find the best route out of the shallows. I spot a channel between one of the fingers of the oyster beds that will lead us to deeper water. As I push off to the grating sound of oyster shells gouging my hull, a big bull redfish roils the water in front of me.

Redfish, or red drum, love to laze in these channels or cuts and wait for the tide to bring food to them. Catching one of these beauties from a kayak on light spinning gear is an adrenaline-pumping experience that you won’t forget. One afternoon on a falling tide, I hooked a redfish that stripped 100 yards of four-pound-test line off my reel and towed my kayak around for more than 30 minutes. In the end, I had to crawl out of the kayak onto the finger of an oyster bar to land and release the 26-inch monster.

Within a few minutes, Peggy and I work our way clear of the maze of oyster bars (after I collect a couple dozen of the mollusks in the gunny sack I sometimes carry with me) and are into deeper water. In Apalachicola Bay, however, the word “deep” is a relative term. With the exception of the middle of the bay, where depths average about nine feet, the prime kayaking waters along the mainland marsh and river environment and the bay side of Apalachicola’s barrier islands rarely exceed a depth of three feet.

Peggy and I are exploring St. Vincent Island, a triangle-shaped National Wildlife Refuge four miles wide and nine miles long. For an introductory experience to the bay, St. Vincent can’t be beat because of the diversity of its coastline and its variety of flora and fauna. It’s also easy to access the island by crossing Indian Pass, a narrow 200-yard cut between the mainland and the island. Camping is not allowed on the refuge, but Indian Pass has a privately owned campground for RVs and tents as well as a small store. Another option is to launch from Indian Pass, paddle west along the bay side of the island and stay overnight at a primitive campsite on the western tip of Little St. George Island, which is separated from St. Vincent by half-mile-wide West Pass.

For this trip to St. Vincent, I have mapped out a route from Indian Pass along the bayside coast with a side excursion up Big Bayou, a lagoon that extends about three miles into the northwest corner of the island.Our first stop is an Indian midden located on a sandy beach where the island reaches into the bay in a curved little half-mile-long peninsula. Scattered along the beach are mounds of oyster shells, the dinnertime detritus of a lost civilization that a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service timeline on the island says dates back to 240 A.D. As we stroll along the beach, we come upon a number of shards of intricately decorated pottery. The midden is marked with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service signs that appeal to visitors to enjoy the site but not take any relics away.

At one point in its history, St. Vincent was developed by private landowners into a game preserve that included a variety of Asian and African wildlife. The Fish and Wildlife Service purchased the island in 1968 and rid it of its collection of exotic animals, with one notable exception: The island is still home to a large population of the huge sambar deer, with their big Mickey Mouse ears. A native of India, the sambar can reach 900 pounds, and seeing one of these giants is a treat. Catching a glimpse of one from the beach is unlikely, but sometimes you can see them from a trail system that borders a string of lakes at the western end of the island (more about this later).

Initially, the Fish and Wildlife Service established the refuge for waterfowl, but the island’s mission has been broadened to include the protection of a habitat for a range of endangered species, including the red wolf, Southern bald eagle, piping plover, wood stork, American alligator, eastern indigo snake and Atlantic loggerhead sea turtle. It’s also home to a large population of feral hogs.

Upon entering Big Bayou, we stick to the forested south side of the inlet. The north side is dominated by huge expanses of marsh grasses and needle-rushes and is less interesting; the south side borders a thick forest of pine, sable palms, magnolia and live oak. As we paddle west, the water becomes shallower, and the bellow of fleeing herons interrupts the silence as we nose around each point of land. Brown pelicans perch on the remains of decaying posts of some long-forgotten structure, and bitterns, egrets and shorebirds feed along the muddy banks. The fall air is thick with monarch butterflies, resting here on their journey across the Gulf to the mountains of central Mexico where they spend the winter. Overhead, ospreys soar on rising thermals, and a lone eagle coasts high above the beach.

Suddenly, the shallow water comes alive with spawning, torpedo-shaped mullet. All around us, the surface of the water boils, and the noise of their jumping makes me think of corks popping at some mass Lilliputian wine tasting. Nobody knows why mullet jump. Some biologists think they do it to clean their gills, and some think the ripples they create by jumping help orient them to each other so they can form schools. Others believe they just jump for fun, which is the explanation I prefer.

Seeing so many mullet makes me wish I knew how to throw one of the large cast nets that locals use to catch mullet. Unlike my wife, I’m quite partial to a big mess of fried mullet. But a monofilament mesh net that measures 12 feet in diameter wouldn’t fit in my kayak. And a few minutes later, I discover that it wouldn’t be such a good idea to leave the protection of a boat, no matter how small, to wade around in Big Bayou burdened by a cast net. Peggy spots it first. About 50 yards ahead, an alligator floats at the surface. It is completely motionless, its nose aimed at the bow of my boat.

Over Peggy’s objections, I quietly paddle closer to take a photograph. As I reach for the camera, I accidentally bump my paddle against the kayak. The alligator explodes forward like a bay skiff with a 150-horse engine going from a standstill to full throttle. I sit paralyzed as the head and most of the body of the eight-foot gator comes completely out of the water, propelled by its powerful tail. It lunges across the water in my direction, then dives and vanishes from sight about 20 yards in front of me.

As startled as we are, we realize that the alligator was most likely fleeing rather than feigning an attack. But the experience serves as a reminder that, despite its role as an often cuddly symbol of Florida tourism, the alligator is a powerful and dangerous predator. It’s hard to miss seeing alligators on any wilderness kayak trip in Florida, and it’s always a thrill to spot one sunning on a bank or floating like a bumpy log in the water. If a photo opportunity presents itself, just make sure to keep your distance-a full-grown alligator can move its 1,000-plus pounds at more than 30 miles an hour.

We backtrack out of Big Bayou, continue east for about a mile and then turn south down the broad base of St. Vincent’s triangle-shaped shoreline toward West Pass. Strong currents accompany the rising tide in the narrow pass, so we do a ferry-glide sprint across the half-mile span of deep water. Once out of the current, we turn toward the primitive campground on the eastern tip of Little St. George Island.

Like St. Vincent, Little St. George Island is completely undeveloped. As a part of the National Estuarine Research Reserve system, the island is jointly managed by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Primitive camping is permitted at either end of the island and at Cape St. George in the middle, but paddlers are asked to contact the Cape St. George State Preserve in Apalachicola before camping on the island. And when I say primitive, I mean it in the most literal sense of the word. There are no toilet facilities (cat holes are OK), no water and, of course, you must pack out all of your refuse.

St. George was once a continuous, 29-mile-long island. In 1954, the Army Corps of Engineers cut a channel just west of center to allow shrimp boats quicker access to the Gulf. Now, St. George Island is the larger (20 miles long) of the two islands while Little St. George Island includes the westernmost nine miles. Separating St. George Island from Little St. George is the pass known as Bob Sikes Cut. Unfortunately, you can’t launch near the pass from the road system on St. George Island unless you’re a property owner or guest at St. George Plantation, a ritzy private development that covers the entire west end of the island.

The unmarked campground at the western end of Little St. George closest to St. Vincent looks like it’s large enough to accommodate about four to six tents, but during our overnight stay, we are completely alone. The odds are that you will be too, if you come here, because this is one of the most underutilized campsites on the bay. Driftwood and deadwood fires are allowed but cutting live trees, of course, is not. We soon have a glowing bed of coals for steaming the oysters I had collected earlier.

My oyster-cooking technique is easy and avoids the need to shuck the oysters, a tricky and dangerous operation for someone who hasn’t tried it before-one slip of an oyster knife, and you have a nasty hand wound. I dig a three-foot by one-foot trench in the sand and build a small fire at the bottom (commercial barbeque charcoal is OK, too). When a bed of coals has formed, I spread them out, place the oysters on a folding backpacking grate that spans the trench and cover them with the wet gunnysack. When the steam causes the oysters to open, they are ready to eat. The only other accompaniment necessary for a gourmet feast is a squeeze bottle filled with a concoction of ketchup, horseradish, Worcestershire sauce and Tabasco sauce.

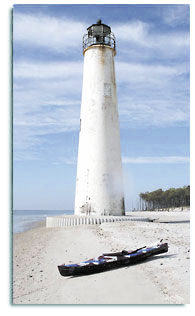

The nighttime breeze is just cool enough to make for pleasant sleeping, and the next morning dawns clear. Our last objective for this trip is an old lighthouse located about three miles down the coast from the campground. The abandoned lighthouse, dating from 1833, is located on the beach at Little St. George’s broad midsection, which is dominated by a forest of live oaks, native palms and pines. As a result of beach erosion, it is often surrounded by water at high tide. You can picnic at the lighthouse if you want to explore some of the sandy trails that meander across the little cape, but overnight camping is not allowed.

As you walk the trails, you may notice metal plates sticking out of some of the larger pine trees. They are remnants of a 19th-century turpentine industry. The brick chimney of an old home site serves as a reminder of the people who tended the lighthouse throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. The island is also rich with wildlife, including several kinds of box turtles, raccoons, ospreys, great horned owls and a wide array of frogs, lizards, insects and shore birds. You’ll want to keep an eye out for rattlesnakes and cottonmouth water moccasins. I’ve never encountered either species, but I’m told they often come out to sun themselves on cool winter days.

The gulf side of Little St. George has some of the most pristine, sugar-sand beaches in the U.S., and beachcombers will find many beautiful shells here. It’s also a prime nesting area for the loggerhead turtle. Kayakers who can bear summer season mosquitoes and heat can join the volunteers who help protect turtle nests against marauding raccoons and other predators. (See “Accessing Apalachicola,” p. 46, about how to contact the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve or the Apalachicola Bay and River Keepers for information on participating.) On the bay side of the island, the ornate diamondback terrapin-what biologist Verle Barnes calls “one of the prettiest little turtles in the world”-swims the lagoons and basks in the mudflats.

After having lunch at the lighthouse, we telephone a friend (Apalachicola Bay has fairly good cell-phone coverage) to pick us up in his powerboat for a quick return to Indian Pass. For visitors, the entire round trip from Indian Pass-along the bay side of St. Vincent, across West Pass to Little St. George, up the gulf side of Little St. George to the lighthouse and back to Indian Pass-is no more than 25 miles and can easily be completed in two days.

Another great side trip, which you can take in place of or in addition to the paddle to the Cape St. George lighthouse, is to explore the chain of four interconnected lakes at the eastern end of St. Vincent Island. About midway along the broad end of the island is a collection of shelters used by hunters during the deer and pig hunts that are permitted on the refuge in the fall. Near these shelters is a tidal creek that connects with the lakes. The creek is too small and winding for large touring kayaks but can easily be navigated by smaller, recreational kayaks. Touring kayakers can leave their boats on the beach and explore the lakes along a system of trails that is not marked but is easy to navigate if you stick to the high ground. The island is also laced by a network of sand roads, formerly used by loggers. The roads are numbered and lettered (numbered roads run north-south and lettered roads run east-west), and frequent signage makes it relatively easy to navigate the island.

Another great side trip, which you can take in place of or in addition to the paddle to the Cape St. George lighthouse, is to explore the chain of four interconnected lakes at the eastern end of St. Vincent Island. About midway along the broad end of the island is a collection of shelters used by hunters during the deer and pig hunts that are permitted on the refuge in the fall. Near these shelters is a tidal creek that connects with the lakes. The creek is too small and winding for large touring kayaks but can easily be navigated by smaller, recreational kayaks. Touring kayakers can leave their boats on the beach and explore the lakes along a system of trails that is not marked but is easy to navigate if you stick to the high ground. The island is also laced by a network of sand roads, formerly used by loggers. The roads are numbered and lettered (numbered roads run north-south and lettered roads run east-west), and frequent signage makes it relatively easy to navigate the island.

On previous trips, we have explored many of these roads by foot. Early morning and evening are the best times for viewing wildlife, especially for catching a glimpse of the huge sambar deer as they feed along the fringes of the lakes. These bodies of water, which increase and decrease in size according to the amount of rainfall they receive, are also home to resident and migratory birds, including wood ducks and bald eagles. The sambar deer is elusive, but the island’s wild pigs, raccoons, ghost crabs and terrapins are seen frequently. The lake system is also home to a large alligator population.

St. George is a prototypical north Florida beach community with concrete block cottages from the 1950s, condos from the ’60s and ’70s and new multi-million-dollar homes. However, the east end of the island is protected by the St. George Island State Park-eight miles and nearly 2,000 acres of beaches, dunes and pine woods. Visitors can access four miles of beach and bay along the park’s main drive; the last four miles are accessible only by foot and boat. The park has two boat ramps for reaching Apalachicola Bay and a beautiful network of coves, sloughs and marshes. The park also has 60 campsites with electric and water hookups connected to the park’s road system and a primitive campsite at Gap Point, which has space for more than a dozen tents. The primitive camp is accessible only by boat or trail. Again, take your own water and dig your own latrines.

The bay side of the park is a less strenuous alternative to a St. Vincent/Little St. George excursion and makes a good conditioning trip. There is a public boat launch at a campsite located less than a mile west of the park entrance exclusively reserved for organized youth groups. Kayakers can launch from the site and explore a small bay, slough and island, then spend the night at the Gap Point campground about a mile away. In keeping with my experiences on Little St. George, I have been completely alone the three times I’ve camped there. But park officials say it is a good idea to call ahead for a reservation.

Protecting the little bay from St. George Sound is Goose Island, a 50-acre oasis of pine trees, tidal inlets and eagle nests about 500 yards from the boat-launch area. The island is surrounded by a necklace of oyster beds and some great fishing spots. The authoritative guide to fishing these waters is John B. Spohrer’s Fish St. George Island, Florida-a must-buy paperback if you are interested in dropping a hook. You can purchase it at most tackle shops and bookstores in Apalachicola.

“The oyster beds are the basis for the rich chain of marine life that supports a thriving resident population of redfish, trout and flounder plus regular yearly visits by tarpon, cobia and Spanish mackerel, among others,” Spohrer writes. “If Jack Nicklaus designed fishing courses, this would be his. The course plays like this: Mullet, crabs and other bait find shelter and copious food in the shallow waters between the bars. When the tide starts going out, it washes these tidbits out into the deeper water just beyond the bars. When the food washes out, they eat it, hooks and all.”

The smallest island in the chain of barrier islands that ring Apalachicola Bay is Dog Island, which is located across East Pass about a half mile from “big” St. George. It is home to 100 or so weathered vacation homes, but much of the island is being preserved in its natural state through the efforts of the Nature Conservancy and the Barrier Island Trust. The seven-mile-long island is accessible by ferry from the mainland.The shoreline matches that found on St. George.

As beautiful as Apalachicola Bay is, no trip here is complete without visiting the great Apalachicola River and its tributaries of creeks and marshes. The Apalachicola River is the only river in Florida that has its source in snow-fed streams. These streams originate in the Appalachian foothills and the Piedmont Plateau of Georgia and North Carolina, some 500 miles to the north.

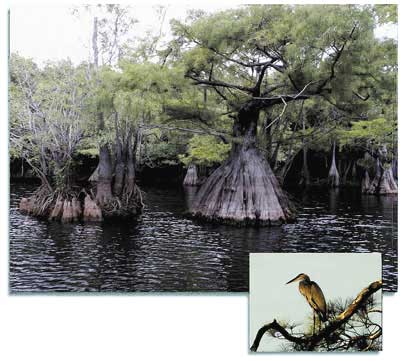

The estuarine area that fringes the northern end of the bay offers a range of kayaking experiences through meandering creeks and sloughs, such as Owl Creek. These creeks are lined with some of the largest stands of cypress and tupelo trees in the world. When the trees flower each spring, beekeepers from miles around bring their hives into the swamp by boat and collect up to 350,000 pounds of the rare tupelo honey each season. Tupelo honey is prized because it never crystallizes and has a unique piquant flavor. The river environment is also home to more species of freshwater fish than are found in the entire state of California.

The river drainage basin has the highest diversity of reptiles and amphibians in the United States and Canada, including more than 40 species of amphibians and 80 species of reptiles. In addition to the indigo snake and loggerhead turtle, among the rare species are the southern dusky salamander, the gopher frog, and Barbour’s map turtle. More than 50 species of mammal are also found within the Apalachicola basin, including opossum, bats, rabbits, foxes, weasels, black bears, mink, bobcats, coyotes, deer, feral pigs, bottlenose dolphin and the West Indian manatee. Bird species thrive in countless numbers. The state has recently published a paddling guide to this estuary, including both one-day and multi-day trips (see “Accessing Apalachicola,” p. 46, for details).

Visitors should also reserve an afternoon for exploring the town of Apalachicola, a funky mix of commercial oyster- and shrimp-processing plants along the river with an old-fashioned downtown of shops and restaurants and an oak-shaded historic district of Florida-vernacular houses. Don’t miss the Gorrie Museum, which documents the accomplishments of John Gorrie, a medical doctor who invented the world’s first ice-making machine in the 1850s as a treatment for yellow fever victims. Gorrie died unknown, thanks to the mass media manipulations of Boston ice merchants who were afraid the invention would drive them out of business.

So, when is a good time to kayak Apalachicola? The Florida panhandle has mild, comfortable winters and summers that range from warm to hot, but are always humid. The average summer temperatures reach well above 85°F, with winter temperatures averaging 55°F. Precipitation for the panhandle area typically exceeds 60 inches per year. August and September are the peak months of the hurricane season, which lasts from June 1 through November 30. For kayakers wishing to avoid the humid Gulf Coast summers, the best times of year to paddle are the fall and spring, specifically October, November, April and May.

As a former Alaska jingoist, I can still dredge up superlative-packed stories about kayaking the panhandle of Alaska as quickly as I can filet a silver salmon. But in Apalachicola, I have found a kayaker’s dream amidst the last remnants of the old Florida-a Florida before Disney. When old Walt first eyed Florida for his east-coast version of Disneyland, he dispatched an exploratory mission to the St. Joe Company, the largest landowner in Florida, whose paper mill 20 miles down the road from Apalachicola was the economic lifeblood of the region for generations. St. Joe corporate officers reportedly refused to meet with Disney because “we don’t do business with carnival people.” I like that kind of isolationist fervor.

From the river to the sea, the Apalachicola area of northwest Florida encompasses what environmentalists and naturalists agree is one of the most pristine, resource-rich marine systems left in the Lower 48 states. At more than 200 square miles, Apalachicola Bay offers kayakers a diversity of experiences that will satisfy novice and experienced kayakers alike. Beginners will like the shallow, protected waters and sugar-sand beaches, while veterans will appreciate one of the last true wilderness kayaking experiences in U.S. coastal waters.