A fatal kayaking accident in Baja brings up issues of responsibility and how to approach other paddlers when you think they may be heading into a situation beyond their abilities.

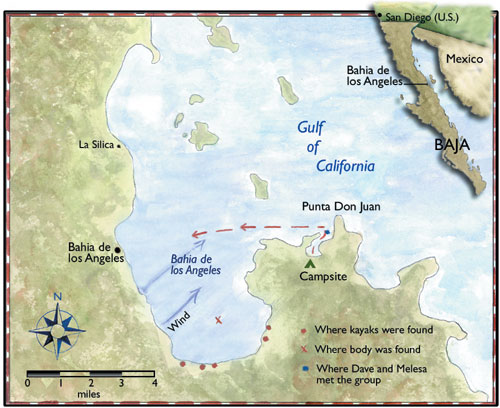

The sun had just dropped below the horizon in a brilliant shower of red and gold, and the sky was growing dusky purple as we paddled into the cove near Punta Don Juan off the coast of Baja, Mexico. This is the last cove to the south in the expansive Bahia de Los Angeles, or L.A. Bay for short, a paddling paradise known for its great snorkeling, fishing and diving. My partner Dave and I were happy to reach shelter before dark after setting out from the town of Bahia de Los Angeles so late in the afternoon.

As we coasted around the point, pelicans dived for their dinner, dropping vertically through hundreds of feet of air to pierce the water and strike fish swimming several feet beneath the surface. Just after rounding the point, we encountered a small group of paddlers heading out toward L.A. Bay from the mouth of the cove. We were practically on a collision course, and as we drew close, all of us stopped.

“What are you doing heading out in the dark?” I asked the five college-age paddlers in a somewhat joking tone but with underlying curiosity. “We’ve been trying hard to get in before it gets dark,” I added. They laughed and shrugged and told us about some great clamming they’d found on the beach they had just left. Dave asked again what they were up to.

They said they felt like they just needed to get back to town. They said goodbye and set out across the quickly darkening L.A. Bay, singing songs and joking about clams, boats and bugs. It was going to be a moonless night, and they had a four-mile crossing ahead of them.

“Boys,” I sighed to Dave. “Only boys would set out in the dark like that.” Just after we landed, the wind started picking up—and up, and up. It was coming off the land, driving the hot, dry air of the desert toward the cooling water and out to sea. Soon we were staking out the tent’s guy lines and huddling together in our windbreakers as we cooked dinner.

“I hope they’re OK,” Dave said as we ate.

“I hope they stick together,” I added.

“I wonder if they made it to town yet with this wind. They’ve got to be going nowhere fast if they’re paddling against it. Maybe they’ll turn around and come back here,” Dave said.

“Do you think they have headlamps or wetsuits?” I asked.

The Missing Paddler

The next morning, I was clamming in the area that the boys had told us about, scooping them up by handfuls, when a boat pulled up. Miguel, who owns the campground where the boys were staying and had rented them kayaks, was out looking for one of the boys. Only four of the five had made it across the bay the previous night. Miguel had received a call that morning from a friend who had recognized one of the rental kayaks sitting on shore on the other side of the bay.

“Really? Oh no,” Miguel had said, then headed out in his panga, a local style of motorboat, to see what was going on. He followed the shore of the bay, and soon spotted a paddle, a kayak and the paddler who had left them on the beach. The young man was one of the five paddlers. He had just started walking back toward camp when Miguel pulled his panga along shore and asked if he was OK. He said he had just reached shore and was exhausted after spending a grueling night on the water.

“Where’s everyone else?” asked Miguel.

“I don’t know,” the young man replied. “We got split up.”

Miguel continued along the beach and found two of the other kayakers walking down the shore toward camp and another one walking along a different spot on the beach. One kayaker was still missing. The four young men on the beach had not yet caught up with each other and didn’t realize that one of them hadn’t made it ashore yet. T

here was no sign of the fifth kayak on the beach. Miguel scanned the bay with his binoculars and saw a red kayak floating in the middle of the bay, but no one was with it. He was hoping that the fifth paddler had reached shore and had left the kayak where the rising tide could have floated the boat and carried it out from shore. If that was the case, he might find the missing boy walking down the beach like the others.

The four kayakers who had reached shore were utterly exhausted, and were not only too tired but too inexperienced to take part in the search. They stayed at the campground, answered questions from the authorities and called the missing boy’s mother.

After listening to Miguel’s story, Dave and I spent the better part of the day paddling the bay, looking for the missing kayaker. There are no Coast Guard or search-and-rescue teams in Mexico, so Miguel, Dave and I were the only ones looking. We skirted the coastline, searching everywhere for the telltale flash of yellow or orange that might be a lifejacket. We were hoping we would see the young man—tired, wet and scared, but very much alive—washed up on shore. We spent the day monitoring the VHF radio and paddled up to fishing boats to ask if they had seen anything.

We radioed out on channel 16, the emergency station, to see if anyone knew what happened to the lost kayaker.

“Anyone, anyone. Come in, anyone. Does anyone have any information on the missing kayaker from last night?” I spoke hesitantly into the speaker.

A minute or two later a female voice answered. “Did someone out there call about the kayaker?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Who is this?” the voice on the other end asked.

“We saw his group set out last night and have been looking for him today,” I said.

“Well, they found his body over at Punta Rincon. They’re waiting for the authorities.”

There was nothing but silence for a while as Dave and I digested this.

“Thank you,” I finally said weakly, forgetting the over-and-out rules of radio contact.

Dave still held out hope, prodding me to ask the final question. Yes, they found the body but…

“So he’s not alive then,” I asked, already knowing what I was going to hear.

“That’s an affirmative.”

Later we learned that Miguel, after combing all the points and islands, had searched the bay one more time and found the missing kayaker’s body floating far from shore. Dave was wracked with guilt. “I should have stopped them,” he kept saying. “I should have told them they were being dumb and they shouldn’t go.”

“Who could have known the wind was going to pick up like that?” I asked him. “And you said just yesterday you wouldn’t mind paddling in the dark, but how could we know how much experience they had?”

At the time the group left, the conditions weren’t anything we wouldn’t have gone out in ourselves, but the rising wind quickly created conditions that they were not prepared to handle.

The group hadn’t been scheduled to return the kayaks to Miguel’s Campground until the day after we saw them heading across the bay. For some reason, they decided to head back to the campground early and make the passage across the water that night instead of waiting until morning.

Miguel told us that he’d asked why they tried to come back early instead of camping the last night and waiting for daylight to cross the bay. “They said they had been thinking about fish tacos and drinking tequila. And when they rented the kayaks, they said they had experience, but now I’ve learned only one of them had any experience, and he’s the one who died!”

The account from the four survivors was that they had stayed together for the first hour or so, but then the wind split them up—three one way and two another. Then the two got separated, and only one of them made it back to shore. The coroner who examined the body of the fifth kayaker listed hypothermia as the cause of death.

I thought about everything we could have told the group, and how all the information in the world is useless if it isn’t shared. I felt so deeply and painfully sorry for the boy’s mother who would just now be hearing she would never see her son again. I thought about a cold, dark and lonely death.

This incident raised a lot of questions for Dave and me. Should we have asked the group if everyone had a headlamp so they could keep track of each other in the dark? Should we have checked to see if they were wearing wetsuits? As the more experienced kayakers, did we have an obligation to do something?

We had questioned what they were doing but hadn’t asked them specific questions about their gear or level of skill. We chatted about superficial things in spite of our feeling that the circumstances they were setting out under were strange. Had we talked with the group about their preparedness instead of just the best place to camp in the cove, maybe we could have been more certain about their capabilities and things would have played out differently.

“It was pretty obvious right away that they didn’t have any experience,” said Dennis, a college-level outdoors professor who was camped next to the group the night before they left on their trip. “I asked them, ‘Do you have tide tables?’ They said, ‘Do we need them?’ I asked, ‘Do you have any maps?’ They said, ‘Do we need those, too?’” Dennis dropped his shoulders, shaking his head as he recalled the conversation. He too must have felt great sadness and regret that in his brief encounter with the five, he could not have found a way to get them to understand the risks they failed to see.

“The Westerlies pick up so fast around here,” Dennis said. “I’ve paddled up and down this coast in different sections, and this is the most dynamic area there is. The wind can pick up in 15 minutes and be blowing 40 miles an hour.”

The wind is always a concern for kayakers paddling in Baja in the spring. Dave and I had just finished sitting through a windstorm for three days, and it continued to be windy off and on all week. While the kind of land breeze that overtook the five is not a daily occurrence, it happens often enough to be a consideration for anyone boating in the area.

In years past, kayakers seldom crossed paths with each other—the novelty of seeing other paddlers was reason enough to go talk with them and find out where they came from and where they were going. Now, tour groups pass each other going back and forth along the same well-used strips of coastline. They don’t want their outdoor experience interrupted by seeing other people, so they don’t approach them in the first place. Groups of kayakers may camp on the same beach within a few yards of each other but remain as distant as two strangers sitting next to each other on a bus. Most groups we encounter in the wilderness don’t even make eye contact with us. And it’s not just while paddling: it can be a part of any wilderness experience.

Sharing information used to give us the benefit of other paddlers’ experience. But now with kayaking becoming ever more popular, people may take to the water with little or no knowledge of safe paddling practices. How do you approach someone when you think they may be heading into a situation beyond their abilities? How do you find out what their experience level is? How can you make sure they are prepared to deal with situations that arise without offending them? Does it matter if you offend someone if you are trying to pass along important information about risks they may not be aware of?

I decided that from that point on, I wouldn’t worry about offending kayakers if I felt their abilities were a poor match for the risks they were taking on.

The next morning, the water started out as perfect glass. It was the kind of day made for kayaking. Our route took us past tiny islets covered in saguaro cactus. As the sun blazed, a man with no hat, sunglasses or shirt paddled a bright red sit-on-top across the bay.

“He’s going to turn the same color as his boat,” I joked to Dave. Even with such hot weather, sunburn wouldn’t be the only risk he’d face. Hypothermia from an unexpected swim could also pose a threat.

Our boats were packed and we were doing a last check before shoving off when a group of three kayakers approached the beach—more college-age boys. They steered away from us and landed on the other end of the beach. They looked very much like the five paddlers who had been scattered by the wind. They were young and energetic, ready to take on the world and free from worry. I couldn’t stop thinking about everything we could have said to the first group, and decided not to make the same mistake again. I took a deep breath and walked over to introduce myself. I asked if they had heard about the incident.

Only one of them had heard of the accident, but he had decided not to tell his friends about it. He said he didn’t want to start their trip off on a down note. I thought it was absurd not to talk about the dangers you might face on a trip like this beforehand, especially in light of what happened last night.

“Yeah, but that guy wasn’t wearing his lifejacket,” he said in an offhanded sort of way.

“Yes, he was,” I said. “He didn’t drown. He died of hypothermia.” The two other boys were amazed someone could die of hypothermia here where it was so warm. “Yeah, but try swimming,” I said. “In the water, you can get really cold after about 15 or 20 minutes. It’s almost unbearable after an hour. The time for clear thinking and good strength and dexterity starts ticking away from the moment you hit the water. You need to be prepared for the water temperature, not the air temperature. Do you guys have wetsuits?” They didn’t.

“Yeah, but I guess if you fell out of your boat you could swim to shore,” said the same one who was so sure of himself. “That would keep you warm.”

I just said, “Have you ever tried swimming five miles against a headwind?” This was just the kind of a “downer” conversation he didn’t want to be involved in, so he excused himself to go fishing.

I was frustrated. Here I was, making an effort to communicate with obviously less experienced kayakers, trying to get the seriousness of what they were attempting across to them, and I was getting the big blow-off. But the other two seemed genuinely interested in what I had to say. “If it gets windy out, head for a cove immediately. And no matter what, stick together,” I said.

We asked them if they had maps and showed them where the little bailout cove was on their mediocre chart. We talked to them about how to steady someone’s boat after a capsize so the paddler can crawl back in from the other side.

It was easy to see that this was their first time out in kayaks. They didn’t have any idea what to do if the wind picked up or how to plan for other emergencies. After imparting a few more words of wisdom, Dave and I wished the two boys (who didn’t mind hearing the downer information) a good journey. We told them about the excellent clamming spot and emphasized again to keep a close eye on the weather and each other, then headed out to sea.

It had been easy to open up a dialogue with the second group of kayakers because of what had happened the day before, but sometimes it’s not so easy. People generally don’t want their inexperience pointed out to them.

As we left L.A. Bay, a sheet of glass covered the ocean, rippled only by the drops falling from our paddles and the slight turbulence of our wakes. I watched Dave’s reflection on the water as he paddled alongside me. Our early start that morning let us take advantage of the tendency for Baja weather to be better in the morning. It also let us catch a free ride on the current making its way out of the Sea of Cortez, rushing past the islands on its way to the Pacific.

It was hard to imagine tragedy on a day like that. The sea was calm and clear, and you could see through 50 or 60 feet of water to the white sand and kelp-covered rocks and coral below. Another day simply made for paddling, and after all the wind and rough seas lately, I appreciated the calm that much more.