Real-life capsizes don’t often happen in flat, calm conditions. If they do, then a rescue rarely poses a problem. But in much more challenging conditions, such as strong tidal streams, vicious winds and breaking waves, it may be essential to get a paddler back in the kayak as quickly as possible. A speedy rescue can prevent an incident from turning into an epic and can make you and your paddling friends into a safer kayaking unit.

Preparation is the name of the game. Making sure everyone in the group knows what to do in the event of a capsize will significantly boost the group’s overall safety. Communication is crucial. Practice may not always make perfect or permanent, but it will help highlight the difficulties that “real” capsizes cause, and it will develop a system whereby a group has a better chance to rectify the situation.

Preparation is the name of the game. Making sure everyone in the group knows what to do in the event of a capsize will significantly boost the group’s overall safety. Communication is crucial. Practice may not always make perfect or permanent, but it will help highlight the difficulties that “real” capsizes cause, and it will develop a system whereby a group has a better chance to rectify the situation.

Generally, when someone capsizes, it’s because the conditions have become, even if just momentarily, too difficult for the paddler to remain upright. Ideally, the capsized paddler would roll back up on every occasion, but in reality, that isn’t going to happen. If the capsized person bails out, it usually means that the conditions for an assisted recovery will not be straightforward. Capsizes that occur where there is danger posed by rip tides, breaking waves or rocks require swift and decisive action. Let’s look at a technique I teach called an “over-the-side speed rescue.” This is the only assisted rescue technique I teach to my students, and it’s the one I use in nearly all rescue situations.

Someone capsizes and takes a swim. This swimmer should shout or blow a whistle to alert the rest of the group. Anyone in the group who sees the capsize should do the same. It’s important that the group remain together: Even if some of the paddlers in the group are not needed to assist in the rescue, they should stand by and not proceed until the rescue is complete and everyone is able to paddle again.

If the kayak is upside down, the swimmer should leave it that way and make his way to the end of the kayak. It doesn’t matter whether he goes to the bow or the stern. He should go to the safest end if there is one and if the option exists to do so. He should also keep hold of his paddle. Allowing the paddle to float away just creates another problem to deal with and can burn up valuable time or put others at risk. Paddlers may wish to consider using a paddle leash when appropriate to the circumstances so that the paddle can’t become detached. It’s worth practicing with the paddle tethered to the boat to see if you have a preference.

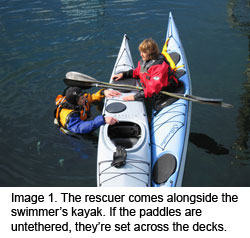

The rescuer approaches and comes alongside the capsized kayak. In rough water, it may be best to approach the middle rather than the ends of the capsized kayak, and be aware of the danger posed by the rolling and pitching of a semi-submerged boat. The orientation of the two kayaks doesn’t matter. The rescuer doesn’t need to align the kayaks so that the bows and sterns are facing the same way or opposite ways, as in other rescue techniques. Having to maneuver and turn a sea kayak around in calm conditions can be time-consuming enough; to do so in rough waters under pressure to rescue someone wastes valuable time and leaves the swimmer in the water much longer than is necessary. It’s generally recognized that body heat is lost about 20 times faster to water than it is to air. Even dressed for the conditions, cold water will have an adverse impact on the swimmer. The faster you get someone out of the water the better.

There’s no need to try to remove any of the water prior to getting the swimmer back aboard. Taking the time to drain the cockpit just leaves the swimmer in the water longer. If, say, the capsize took place in a cave or near some dangerous rocks and the kayaks were being swept onto them, then trying to empty the kayak would leave both rescuer and swimmer in the danger zone for longer. The main aim is to get the swimmer back into his kayak and out of danger as quickly as possible. The rescuer and swimmer can work together to flip the kayak right side up. Righting the kayak with the help of the swimmer puts much less strain on the rescuer. With certain rescue techniques, the rescuer lifts the kayak to drain out the water, but this can pose a real risk of back injury, especially in rough or moving water.

After the swimmer’s kayak has been righted, the rescuer leans onto it and, by doing so, makes a very stable raft. In rough conditions, this provides stability for the rescuer and a solid platform onto which the swimmer can climb. At this stage, some rescuers consider using a stirrup to help rescue the swimmer, but again, this method leaves the swimmer in the water longer. Even dressed in full immersion apparel, a swimmer will weaken if left in the water for too long. The advantage offered by a stirrup may not be necessary, as you’ll see.

The swimmer makes his way to his cockpit, or just aft of it, on the outside of the raft. It is important that the swimmer does not let go —properly fitted deck lines will prove invaluable here. If the swimmer’s paddle is not tethered, this is a good time for the swimmer to pass his paddle to the rescuer. By coming on the outside of the raft (rather than in-between, as in some rescues), the over-the-side speed rescue has several important advantages. A swimmer that comes between the kayaks as a way to get back aboard always has the risk of being hit, usually on the head, by one of the kayaks. As most sea kayakers paddle without a helmet, this is a real hazard. The risk of impact is obviously less if the swimmer comes over the side. It’s also easier for the rescuer to hold the two kayaks together if the swimmer isn’t between them, forcing them apart.

The swimmer reaches across his cockpit, or just aft of it, with both hands and grabs the coaming on the far side. The rescuer grabs hold of the swimmer’s PFD shoulder strap (see Image 2). It’s better if the rescuer uses her “outside” hand for this (the hand farthest from the swimmer). She will be in a much better position to pull the swimmer out of the water and across the rafted boats. By reaching across with the outside hand, the rescuer twists at the waist, readying the large muscles of the torso for the pull.

The next step is quite crucial, especially if the swimmer is larger and/or heavier. The command from the rescuer is “1-2-3 JUMP!” The swimmer kicks his legs to the surface (see Image 3) and, on the word “JUMP,” pulls himself onto the raft. Simultaneously, the rescuer pulls on the PFD (see Image 4). Twisting at the waist provides a powerful pull—by leaning back, the rescuer can exert an even stronger effort. Under some conditions, it may be possible for the rescuer to place her free hand on the near side of the swimmer’s kayak to provide something to push off and to keep it fairly level when the swimmer comes out of the water.

In rougher conditions, the rescuer can use that free hand to keep the raft together. If the actions of both swimmer and rescuer are sufficiently coordinated, the swimmer will land well up on the raft face down. As long as the rescuer hangs onto the swimmer, the raft will keep together, and the rescuer can focus her efforts on helping the swimmer get out of the water and onto the kayaks. This can be a great benefit to a swimmer who doesn’t have good upper-body strength or has been weakened by cold water.

The rescuer directs the swimmer which way to turn to get into the cockpit. As the swimmer begins to slide into the cockpit, the rescuer holds the rafted kayaks together with one hand (see Image 5). It helps if the swimmer has practiced getting into the cockpit quickly so that the center of gravity is lowered as soon as possible. If the swimmer is not familiar with reentry techniques, the rescuer should provide directions with short, simple and direct commands. A swimmer is quite likely to be fearful and confused and in need of clear and concise direction. It may be possible for the rescuer to use one hand to hold the kayaks together and the other to help the swimmer into the cockpit to speed up the rescue.

Once the swimmer is back in his kayak, the rescuer must hold the two kayaks together (see Image 6). The swimmer will most probably need help attaching his spray deck. If the kayak has a built-in hand, foot or electric pump, then the spray deck can be fitted and the water pumped out. If there is no integral pump, and the swimmer is wearing a conventional spray deck, the rescuer can use a hand pump. This may be easy to do in calm conditions before the spray deck is reattached, but if there are waves breaking over the kayaks, it will be necessary to partially cover the cockpit with the spray deck, leaving a small gap at the side to insert the hand pump.

Pumping out a heavily swamped kayak is quite energy sapping. In the over-the-side speed rescue, both rescuer and swimmer can take turns at using the hand pump and holding the raft together. It’s worth trying to get out as much water as possible. A second capsize will be far more likely if there’s water sloshing around in the cockpit.

If the kayaks are facing in opposite directions, have the swimmer move to your bow and lean across it for support. Use a short tether to hold the bow of the swimmer’s kayak near your cockpit. If the kayaks are facing the same direction, have the swimmer move to your stern and hang on there while you short-tether his bow near your cockpit. With the swimmer leaning on and holding the bow or stern, he’ll be in a stable position, and you’ll be able to paddle by reaching over his bow.

Training Tips

Practice this rescue in calm conditions at first, then move out into rougher conditions. Consider wearing helmets to prevent accidental injury. Wear clothing that will allow you to jump into water with impunity. Time how long it takes from the rescuer arriving at the capsized kayak to getting the swimmer seated in his boat (without spray deck fitted). Twenty seconds in calm water is good. Fifteen seconds, and you’re getting it together as a team. Ten seconds is really slick.