I met Audrey Sutherland aboard a kayak mothership in Sitka, AK. It was her 23rd year of kayaking in Southeast Alaska. We motored south along the west side of Baranof Island and anchored in protected, fjord-like bays to go paddling.

Audrey is a brilliantly focused woman. From the mothership’s wheelhouse, she used binoculars to study the shoreline for campsites. At times she would forego launching a kayak and hop in the skiff to expedite a shore visit. She insisted on starting and operating the skiff’s outboard herself. When ashore, Audrey would duck under the spruce and cedar canopy and quickly assess a spot’s camping potential.

She knows the Latin names of countless plants and animals, and she peppered captain Jim Kyle and chef/kayak guide Tana DeSilva with countless questions. Audrey’s a do-it-yourselfer who loves a good hardware store. She’s also very visual: Sitting in the galley, she would often grab a napkin and draw a simple diagram to illustrate a concept.

She has a tremendous store of memories and can describe beach scenes and bear encounters in great detail. She has, arguably, the brightest eyes on the planet. People talk about sunset years. Audrey is full-on 10AM sunshine.

I interviewed her by phone after she returned to her home in Hawaii.

Gary Luhm: When I was invited to spend a week with Audrey Sutherland, I thought, “Wow, a week with the grandmother of sea kayaking.” At least that’s how I perceived it. How and when did you get started?

Audrey Sutherland: Many people were kayaking before I started. After twice swimming the 20-mile north shore of Molokai, towing my gear, I bought a six-foot inflatable kayak, then a nine-foot, and paddled that coast 18 times.

GL: What were those early days like, compared to today?

AS: The same. I’m always discovering new places and learning more each year.

GL: The self-sufficiency of those early trips must have been a great boost to your self-esteem. Today paddlers can buy everything they need to outfit themselves. I wonder if that degrades the end experience?

AS: I buy maybe 10 percent of my gear. The rest I make from scratch or redesign and adapt. Cheaper that way, and fits the need.

GL: You paddled in Hawaii for a long time and then shifted to Alaska, from warm water to cold. What drew you to Alaska? Why didn’t you head for Tahiti or Baja?

AS: I’d been to Tahiti and to Baja. Tahiti is too civilized, and in Baja I always felt I needed a desalinator so as not to use the local meager supply of water.

GL: Southeast Alaska is a challenging place to paddle. What adjustments did you make for paddling there?

AS: I started small; short trips of two hundred miles in sheltered waters, and worked up to 500-mile trips in open seas.

GL: How do you re-supply on longer trips?

AS: I can carry enough for three weeks. Beyond that I send a box of food, charts, film to a post office along the route. On the 900-mile trip from Skagway into BC, I sent five boxes.

GL: You’ve had a number of bear encounters.

AS: Yes, I’ve had 30 bears within 100 yards of me: 17 grizzlies, 13 black bears. One grizzly was five feet away with only a thin sheet of plastic between us. I talk to them. The human voice, more than scent, seems to let them know that I’m an unknown and not to be tested.

GL: How else do you keep yourself safe?

AS: I always wear a lifeline. It’s an eight-foot cord with one end looped and fastened over my left shoulder, the other end clipped with a snap hook to the boat by my right hip.

GL: Chris Duff, who has circumnavigated Ireland, New Zealand, and most recently Iceland, says he trains in the worst conditions, then paddles well below his skill level. Good advice?

AS: His skill level is higher than mine. He has paddled the west coast of Ireland and around Cape Wrath in Scotland. I wouldn’t try either one.

GL: You’ve written extensively about paddling solo. Paddling organizations like the BCU, ACA, and kayak clubs all advocate paddling in groups for safety. Don’t you think it you would be safer paddling in a group? Why do you choose to paddle solo?

AS: I’m safer alone. I prepare in detail. I don’t follow a group schedule. I don’t have to rescue anyone else. I know what I can do and I don’t exceed my abilities.

GL: You’ve paddled or owned a dozen inflatable kayaks. They’re great for portability, but they’re also slow and have a lot of windage. Other portables, like the folders, would seem to me to be a better option for long trips. If you had the technology of today 40 years ago, do you think you would still have paddled an inflatable?

AS: Yes, they are safer boats. For carrying a kayak up and down a beach at low tide my limit is 30 lbs. Folding boats large enough to carry three weeks of gear weigh too much. Inflatable boats vary greatly in speed but I once paddled 22 miles once in 4 hours to catch a ferry.

GL: Do you own a hardshell kayak?

AS: Yes, a nine-foot, 35-pound sit-on-top for my grandson. My son James also has four big hardshells that he keeps in my yard.

GL: You mentioned a number of times that you don’t like surf. But surf is common in Hawaii, and on the outside in southeast Alaska. How do you deal with it?

AS: In Hawaii or in Alaska it is almost always possible to find a cove or a corner of a bay with no surf.

GL: Looking at your paddling accomplishments and reading about your early coastal swims in Hawaii I’d say you’re tough as nails. Yet you say you’re not strong. Why and how does a “not-strong” person take on these types of challenges?

AS: Stamina and ingenuity take the place of strength. I can’t carry a kayak that weighs more than 30 pounds, but I cut rollers from bull kelp and haul the kayak up the shore.

GL: In Paddle My Own Canoe, you state that, “pre-trip conditioning must improve each year to offset the aging process.” You also wrote “when I’m 71, I’ll have to be able to do 71 push-ups.” How do you manage to keep on paddling?

AS: No, I can’t do 71 push-ups. When I get too old and feeble, I’ll make day trips from a base camp or from a cabin.

GL: There’s a passage in the book that reveals some of your motivation. You say, “I come back from these trips feeling like a skinned-up kid, feeling like a renewed, recreated adult, feeling like a tiger.” They must be terrific confidence builders.

AS: More than confidence. Exaltation!

GL: You seem, too, to thrive on problem solving, as you say “the smug satisfaction of finding an ingenious solution to a problem caused by (your) own inadequacy or stupidity.”

AS: That is still part of the fun.

GL: What have you learned from the experiences described in Paddling My Own Canoe?

AS: I learned the basics, and kept on going. There is still a lot to learn.

GL: Has your motivation for paddling changed in any way, as you’ve grown older?

AS: It has stayed the same. Going solo in a wilderness is still my main motivation.

GL: So seeking solitude is a big factor for you. On a recent trip to Cape Scott I carried a satellite phone. I could call my wife every night. What do you think of taking all this technology aboard—the sat phone, the cell phone, the GPS, even a digital camera and laptop or PDA—so you can send a day-by-day trip report, or, God help us, surf the internet.

AS: Why not just stay home?

GL: I’ve heard you say: “Keep it simple.” Would you give that advice to a mainland paddler who doesn’t intend to fly to Tahiti for a paddling trip, but sticks close to home with a high-volume hardshell?

AS: Set a goal for each trip. Ask yourself how light you can go and still stay warm and dry. Will you see more if you go only 5 miles a day? Are you happier going solo? Do you really know this area, its wildlife, its wild food, and its history?

GL: One of your favorite activities is foraging food from the sea. This can be the key to real self-sufficiency. Any comments?

AS: I’m still learning. Yesterday I tried eating a sea cucumber. Definitely not successful—yet.

GL: In our previous conversations you frequently mentioned John Dowd, the founding editor of Sea Kayaker. I had the good fortune of hearing John speak at the 2003 West Coast Sea Kayaking Symposium. He talked at length about the differences between information and knowledge. A lot of information taught to kayakers isn’t useful, he said. What’s required is experience—experiential learning. In other words, information plus the right experience equals knowledge. You seem to have drawn similar conclusions. Comments?

AS: At home I have two sea-kayaking manuals that were supposedly written by experts. In each I’ve tagged more than twenty notes about what won’t work and why. I revere John and his practicality.

GL: Dowd also talked about real and perceived risk. Some would say your solo adventures in Alaska are foolhardy. What is the real risk, and what do you think others perceive the risk to be?

AS: Others think the risk is bears. Read and follow Dave Smith’s book Bear Basics. The real risk is getting into a situation without knowledge of the real dangers. Read your large-scale charts. Try to imagine what circumstances could kill you. Each morning, go through the what-ifs.

GL: How should a novice or one who dreams about expeditionary paddling get started?

AS: Go with a professional group. Paddle with one of the best outfits in your territory.

GL: Say I’m an intermediate-to-advanced paddler, with a few years of experience, a couple of weeklong trips under my belt, and a good pool roll. I’m thinking: Now’s the time to plan a week or two in southeast Alaska. Where should I go for a first trip?

AS: Before you go, make sure you can get back in your boat after a wet exit in 50-degree water. How long does it take? More than 30 seconds and you’ll be too numb to function. For first trips I’d recommend the western Behm Canal out of Ketchikan, or Sitka Sound. Petersburg to Duncan Canal, or Juneau around Douglas Island, and Wrangell to Anan Bay are all good trips too.

GL: I think many paddlers, women especially, regard you as a role model. How do you think you may have inspired others?

AS: Inspiration without nuts and bolts practicality and bit-by-bit efficiency is futile.

GL: Many women often struggle to find a life of their own, with competing demands as mothers, employees and as daughters of aging parents. How did you find time for your adventures? Why was making this time to adventure important to you? What effect did this have on your family?

AS: Before I retired from my full-time job, all of my adventures were for less than ten days each. Each of my four children learned self-sufficiency. We made a list of 25 things they should be able to do by age 16. I could write a whole story on that.

GL: Are you dreaming about padding anywhere new?

AS: The Cook Islands, and new places in Southeast Alaska: around Kuiu, Elfin Cove to Tenakee, around the south end of Prince of Wales Island.

GL: I’m sure you’ll make it happen.

In Greenlandic, the word ‘maligiaq’ means “medium-sized wave.”

In Greenlandic, the word ‘maligiaq’ means “medium-sized wave.”

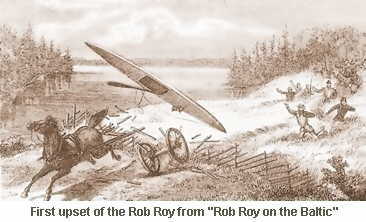

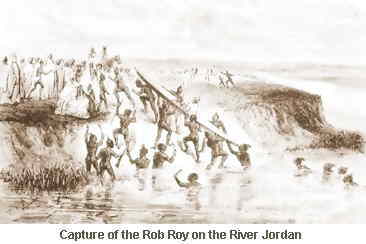

Although MacGregor omits mention of the exact aboriginal lineage of his boats, it is assumed they were based upon his observation of such craft in Siberia and North America. The original Rob Roy, a decked canoe that weighed 80 pounds and was equipped with a lug sail and jib as well as a seven-foot double-bladed paddle, is now preserved in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England.

Although MacGregor omits mention of the exact aboriginal lineage of his boats, it is assumed they were based upon his observation of such craft in Siberia and North America. The original Rob Roy, a decked canoe that weighed 80 pounds and was equipped with a lug sail and jib as well as a seven-foot double-bladed paddle, is now preserved in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England. A window abruptly opens on a harbor full of gaff-rigged work boats, a steamboat that blows a cylinder in a gale, or one of John Ericsson’s fearsome ironclad gunboats. Streets clatter with horse-drawn carriages while, on the green, Bismarck’s troops drill or practice marksmanship.

A window abruptly opens on a harbor full of gaff-rigged work boats, a steamboat that blows a cylinder in a gale, or one of John Ericsson’s fearsome ironclad gunboats. Streets clatter with horse-drawn carriages while, on the green, Bismarck’s troops drill or practice marksmanship.