After taking on supplies at Gravesend,” wrote John MacGregor, firmly establishing the jaunty tone that became his signature, “I shoved off into the tide, and lit a cigar, and now I felt we had fairly started.” Thus begins the literature of sea kayaking and, indeed, of the sport itself.

Although the British Dictionary of National Biography identifies MacGregor (18252892) as a philanthropist and traveler, this eminent though forgotten Victorian single-handedly created a rage for what came to be known as “canoeing.”

Had MacGregor never been born, a Rudyard Kipling or a Robert Louis Stevenson might have had to invent him. The son of General Sir Duncan MacGregor who fought against Napoleon, John MacGregor was an adventurer from the outset.

As an infant, he was rescued along with his parents from a burning ship in which they had set sail for India. MacGregor tried to return the favor as a 12-year-old by nimbly slipping aboard a lifeboat bound for a ship in distress off Belfast, Ireland. Because of his father’s reassignments, MacGregor attended seven schools before graduating Trinity College, Dublin in 1839 with a degree in mathematics. He later entered Cambridge, and subsequently studied patent law. Even before his kayaking escapades, he’d traveled overland through Europe, the Middle East, Russia, North Africa, Canada and Siberia.

In 1865 MacGregor commissioned Messrs. Searles of Lambeth, England, to construct to his specifications the first in a series of seven clinker-built, cedar and oak “canoes,” each of which he christened “Rob Roy.”  Although MacGregor omits mention of the exact aboriginal lineage of his boats, it is assumed they were based upon his observation of such craft in Siberia and North America. The original Rob Roy, a decked canoe that weighed 80 pounds and was equipped with a lug sail and jib as well as a seven-foot double-bladed paddle, is now preserved in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England.

Although MacGregor omits mention of the exact aboriginal lineage of his boats, it is assumed they were based upon his observation of such craft in Siberia and North America. The original Rob Roy, a decked canoe that weighed 80 pounds and was equipped with a lug sail and jib as well as a seven-foot double-bladed paddle, is now preserved in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England.

It measures 15 feet long with a 28-inch beam, is nine inches deep, and draws three inches. Although the Rob Roy’s inflexible bulk eventually fell from favor (the torch taken up 40 years later by Johann Klepper’s folding boat), it put hundreds of paddlers into the waters of Europe and inspired the first circumnavigation of Tasmania.

Buoyant in every sense, MacGregor set off down the Thames, waving merrily to astonished bargemen then venturing into the English Channel where he joined a school of porpoises.

The Rob Roy was then ferried to Europe, where MacGregor explored rivers and lakes in France, Germany, Switzerland, and Belgium. His account, A Thousand Miles in the Rob Roy Canoe (1866), may have been that year’s best seller.

“The object of this book,” he wrote in his introduction, “is to describe a new mode of travelling on the Continent by which new people and things are met with, while healthy exercise is enjoyed and an interest ever varied with excitement keeps fully alert the energies of the mind.”

As the embodiment of this new independent traveler, MacGregor was impervious to the blandishments of hired guides or the security of Cook’s Tours. He set off for the entire summer with a spirit stove, a wooden fork and spoon (cunningly carved at opposite ends of the same stem), one spare button, and nine pounds of luggage.

While his kit might be Spartan, fitting together “like the words in hexameter verse,” MacGregor was an ardent creature of style. He decked himself out in a gray flannel Norfolk jacket (garnished with six pockets), matching trousers, canvas wading shoes, blue spectacles, and a straw boater-plus a blue silk Union Jack for the boat.

To say this six-foot-six vision of sartorial splendor enjoyed creating an effect, whether in life or upon the page, would be an understatement. Because his trips were widely publicized, shipping frequently altered course for a closer look and ashore he received plentiful offers of meals and lodging.

Even when unrecognized, he precipitated a mild sensation. “I drew along side [a small steamer on the Meuse] and got my penny roll and penny glass of beer through the porthole, while the passengers smiled, chattered, and then looked grave for was it not indecorous to laugh at an Englishman evidently mad, poor fellow?”

Nor was he above an occasional prank. Paddling unseen below the Danube’s banks, he indulged a hearty chorus of “Rule Britannia,” much to the bafflement of peasants cutting hay nearby.

When all else failed to get attention, at a Swedish wedding into which he had politely blundered, he entertained guests by igniting a bit of magnesium ribbon apparently carried for just such occasions.

After he paused to form the Royal Canoe Club (H.R.H. Edward, Prince of Wales, Commodore), subsequent expeditions followed hard upon one another. He crossed the Channel and sailed up the Seine in a diminutive yawl (christened, predictably, Rob Roy) at the invitation of Napoleon III, to promote canoeing in France. That became another book in 1867.

A tour of Scandinavia in the previous year resulted in Rob Roy on the Baltic.

MacGregor dumped all sorts of improbable information into Rob Roy on the Baltic, making it a veritable collage of oddities: several maps, the music to “The Swedish National Air,” complete lyrics to “The Björneborgarnes March,” conjurer’s tricks (guaranteed to delight children), and a specimen restaurant menu (with prices).

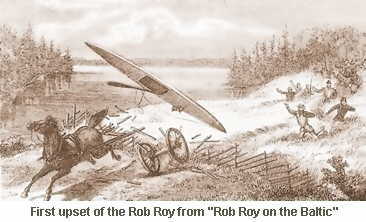

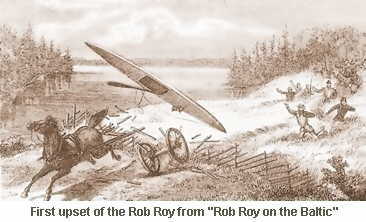

Appendices comment upon the Danish missions and Prussian education. Another appendix is devoted to discussing watertight aft hatches, drip-rings, lee boards, outriggers and a set of bronze boat wheels. (He rejected the wheels because paved roads were still rare and, very much a man of his class, he could afford a few pennies for the local yeomanry to lug his boat into town or portage it by ox cart.) MacGregor also executed three dozen woodcuts, beginning with a dramatic frontispiece depicting the Rob Roy catapulted skyward as a runaway horse and cart crash through a fence.

Though well drawn, the illustrations have a slightly bizarre quality, an exaggeration that may or may not have been intended by the artist, but which is delightful nevertheless. Another, reminiscent of Max Ernst’s surreal collages, depicts the boat transported on a Norwegian railway conveyance powered “by cranks and treadles for the feet, as a velocipede is worked, and to which vehicle there clung as many persons as could hold it.”

Given his prodigious energy, it is perhaps not surprising that MacGregor often expressed himself in the first- and third-person plural: “All hands were piped on deck by the boatswain at an early hour, and the last pair that came up were told off to scrub ship and wash clothes.

Meanwhile, the head cook of the Rob Roy (an ignoramus)…mixed water and oatmeal, and had a round tin plate heating on the flame whereon the mixture was poured. It steamed, it set, it dried hard; and then he removed the plate from the fire, but alas!

The cake would not come off the tin-plate until it was torn away with struggles and a knife; and then all the lower part of the brown cake was covered with bright tin-gone was my only hope of breakfast; for even salt air does not enable you to digest sheet metal.”

When the dog he planned to take along disappeared, he unleashed one of his worst puns, ruing the canine’s absence because he wouldn’t be able to write, “my bark is upon the wave.” Yet despite these lapse and some awkward punctuation, a late 20th-century reader can glide through whole chapters lulled by the utterly familiar: tedious head winds, generous tail winds, fog, makeshift campsites and curious onlookers.

MacGregor carries us thirty or more miles a day, chattering on about encounters with ferocious bed bugs, logjams or a perilous tow from a Dutch cutter. These are balanced with sedate pleasures like fishing or Miss Kjerstin, farmer Svenson’s lovely daughter, who modestly serenaded him on the guitar while he sketched her portrait.

Eventually, however, snagging on some detail, we awake with mild shock and remember that all this took place before the Great War, before the internal combustion engine or household electricity.  A window abruptly opens on a harbor full of gaff-rigged work boats, a steamboat that blows a cylinder in a gale, or one of John Ericsson’s fearsome ironclad gunboats. Streets clatter with horse-drawn carriages while, on the green, Bismarck’s troops drill or practice marksmanship.

A window abruptly opens on a harbor full of gaff-rigged work boats, a steamboat that blows a cylinder in a gale, or one of John Ericsson’s fearsome ironclad gunboats. Streets clatter with horse-drawn carriages while, on the green, Bismarck’s troops drill or practice marksmanship.

Where he may try our patience is in his religious asides. A thwarted vocation for missionary work led MacGregor, who styled himself the “Chaplain of the Canoe,” to distribute reams of Protestant tracts to surprised bystanders, and to make less than generous remarks concerning the “benighted” members of the Roman Church. Overall, his rectitude is not overbearing, and takes a back seat to his proselytizing the gospel of the canoe.

Upon his crossing the four-mile stretch of the Baltic into Denmark, however, we encounter a prime candidate for judicious editing: “The Rob Roy, carried through Copenhagen, of course attracted a great crowd, and the head waiter (being a man of sense) conducted her upstairs, where the ball-room was allotted for a boat-house, and there the canoe rested gently on an ottoman.”

This may be the briefest sample of what, after reading his three kayaking books, one comes to think of as the Rob Roy’s mandatory “triumphal reception” into town. Whether set in a busy Scandinavian city or a muddy Prussian hamlet, this interchangeable narrative staple soon becomes the most tiresome device in MacGregor’s repertoire. Nevertheless, there is one instance where it reaches an amusing pinnacle.

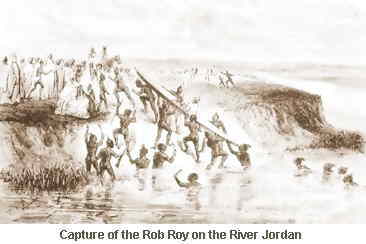

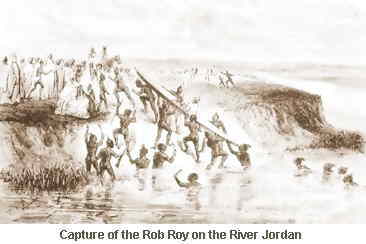

In his Middle Eastern expedition, The Rob Roy on the Jordan, Red Sea, and Gennesareth (1869), he plunges down the Jordan noting with pride how few European travelers ventured down the river’s more remote reaches. He quickly found out why. An entire village tumbled out, brandishing rifles and casting stones.

Several men dove in after him and, although our hero valiantly swatted left and right with his paddle, he was finally cornered in the shallows. Affecting nonchalance, a cocked pistol concealed under his knees, he noted, with characteristic understatement, that “their patience was on the ebb.”

The subsequent scene reads like John Cleese playing “The Man Who Would be King” as a Monty Python skit.

“A dozen dark-skinned bearers,” writes MacGregor, “lifted the canoe and her captain, sitting inside, with all due dignity graciously smiling,” up the bank amid loud shouting, and deposited them inside the tent of the local sheik.

Remaining in his boat, MacGregor doffed his pith helmet, and blithely informed his host that he “would rest at his tent until the sun was cooler.” The startled sheik summoned his counselors. After threats and counter-threats, a couple of surreptitious bribes and much conferring -in which MacGregor sat imperturbable, reading the Times-he was eventually liberated by Harry, his well-armed, fast-talking interpreter.

The book is MacGregor’s most exotic and, despite his studied composure, the expedition clearly had its share of real crocodiles and brigands.

The incarnation of the Rob Roy used on this trip was modified with a removable aft deck, allowing its owner to rig a canvas tent fly, drop mosquito netting, and sleep aboard. MacGregor tried out this arrangement along the newly opened Suez Canal, doing his best to remain solitary, as, in that neighborhood, “any man with five francs, or supposed to have them, is worth killing.”

He remained unmolested except for a jackal who “would neither leave me in peace nor come near enough to be shot.” In his inimitable way, he continued down to the Red Sea, particularly tickled by an incongruous cup of coffee offered him afloat, accompanied by a pair of silver tongs for the sugar. Finally, after steaming on to Beirut, he trudged overland through a foot of snow outside Damascus to find the source of the Jordan. He concluded his adventure shortly after 12 contemplative days on the Sea of Galilee musing on the life of Jesus.

While his writings certainly encouraged numerous amateurs to get their keels wet, there was yet another side to MacGregor. His passion for philanthropy led him to donate the proceeds of all of the Rob Roy publications to charitable causes like the Shipwrecked Mariners’ Society and the National Lifeboat Institution.

He also co-founded the Ragged-School Union’s Shoe-Black Brigade, which sought employment for destitute children. Combining two improbable interests, he raised money for charity by giving public lectures, hamming it up on stage with the Rob Roy, doing quick changes into his canoeing outfit (or, after the Jordan expedition, into a burnoose) and reappearing to wild cheers. Ironically, almost 140 years later – amid a worldwide explosion of kayaking – the man once anointed the “patron saint of canoeing” has been reduced to a footnote.

MacGregor’s works, decades out of print, lie mostly in the hands of collectors and antiquarian booksellers. I found copies slumbering in the closed stacks of the Peabody Essex Museum (in Salem, Massachusetts) and the Boston Public Library. Time had not been kind to them, nor, in the latter institution, was the attendant who delivered the volumes with a mighty thump that resounded painfully down the reading room’s vaulted ceiling.

Bindings cracked, folded maps tore along ancient creases, dog-eared corners fell like withered leaves. Yet, the contents, the story, MacGregor’s indefatigable enthusiasm and wit, have weathered well. If we dare to think of kayaking as having a literature the way fishing does, then MacGregor is our Izzak Walton.

Having recently read Paul Theroux’s Happy Isles of Oceania, I felt I had bounded from one end of kayaking’s literary bookshelf to the other. To MacGregor’s credit, that leap requires far less adjustment for the armchair kayaker than one might suppose.

Despite their very different sensibilities, I could easily imagine MacGregor and Theroux happily switching boats. Their interests are not that different, nor their insistence upon travel on their own terms, their mixed feeling about their fame, their curiosity about their hosts tempered by impatience with some of their hosts’ customs.

MacGregor’s digressions on the shortness of Danish beds, the deceitfulness of Prussian customs agents, and the behavior of English people abroad, find a certain correspondence in Theroux’s mutterings about Kiwi politicians and starch-fed Tongans.

Theroux’s efforts to “toktok” Pidgin English recall MacGregor’s amusing attempts at communication. He gamely passed a phrase book back and forth with his Swedish hosts until a learned doctor arrived for tea and they discovered a language in common: “We talked Latin,” MacGregor notes, “with that circumlocutory elegance which a very slow remembrance of it involves, like pumping water out of a very deep well, with very little in the bucket when it comes up, and not much at the bottom.”

As personalities, each might be the perfect antidote to the other. A good dose of MacGregor’s cheery, indomitable, stiff upper lip can create an absolute yearning for Theroux’s misanthropy, angst and soul-searching, and, perhaps, vice versa, but, while Theroux’s work is still with us, where will we find MacGregor?

Let me confess that I conceived this entire sketch as an introduction to an imaginary, deluxe, lavishly illustrated, amply edited and thoroughly portable MacGregor. Now where is the publisher?

and later organized a relief effort for refugees and POWs from World War I, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922.

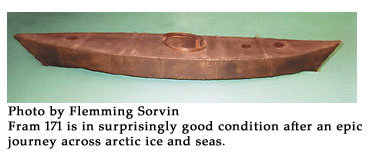

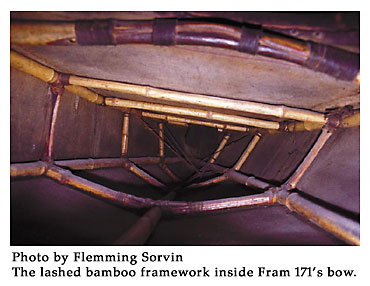

and later organized a relief effort for refugees and POWs from World War I, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922. The museum removed Fram no. 171 from its display on the wall starboard to the giant display of the Fram and placed it down by the keel of the ship for us to work on. The museum indicated that the boat was Hjalmar Johansen’s kayak. We were told that Johansen’s kayak was originally housed at the Ski Museum in Oslo, which still holds the sister kayak used by Nansen as well as other artifacts from the expedition. I could confirm the identity of 171 by the depth-to-sheer measurement.

The museum removed Fram no. 171 from its display on the wall starboard to the giant display of the Fram and placed it down by the keel of the ship for us to work on. The museum indicated that the boat was Hjalmar Johansen’s kayak. We were told that Johansen’s kayak was originally housed at the Ski Museum in Oslo, which still holds the sister kayak used by Nansen as well as other artifacts from the expedition. I could confirm the identity of 171 by the depth-to-sheer measurement. Although MacGregor omits mention of the exact aboriginal lineage of his boats, it is assumed they were based upon his observation of such craft in Siberia and North America. The original Rob Roy, a decked canoe that weighed 80 pounds and was equipped with a lug sail and jib as well as a seven-foot double-bladed paddle, is now preserved in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England.

Although MacGregor omits mention of the exact aboriginal lineage of his boats, it is assumed they were based upon his observation of such craft in Siberia and North America. The original Rob Roy, a decked canoe that weighed 80 pounds and was equipped with a lug sail and jib as well as a seven-foot double-bladed paddle, is now preserved in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England. A window abruptly opens on a harbor full of gaff-rigged work boats, a steamboat that blows a cylinder in a gale, or one of John Ericsson’s fearsome ironclad gunboats. Streets clatter with horse-drawn carriages while, on the green, Bismarck’s troops drill or practice marksmanship.

A window abruptly opens on a harbor full of gaff-rigged work boats, a steamboat that blows a cylinder in a gale, or one of John Ericsson’s fearsome ironclad gunboats. Streets clatter with horse-drawn carriages while, on the green, Bismarck’s troops drill or practice marksmanship.