Over the last 10 years, the standard wardrobe and gear needs of most kayakers have shifted from functional, basic essentials to high-tech, often flashy items created from space-age fabrics and composite materials.

In the midst of all this glamour, the humble spray skirt, for the most part, has changed little. Its basic design, constructed of neoprene or some variation of coated nylon, has remained fairly consistent throughout the last decade. Times, however, are changing.

The spray skirt’s day in the limelight has finally arrived. Though their primary purpose remains the same, many of today’s spray skirts exhibit a trend toward new fabrics, special features and increased functionality. The products in this review provide good examples of that trend.

Put to the Test

In testing the following six spray skirts, I wanted to examine how well they performed their primary purpose—keeping water out of the cockpit. The fit and seal of a spray skirt around the cockpit coaming is a critical safety aspect for kayakers. It is essential that the spray skirt is the right size for the kayak it will be used on.

There is no substitution for trying a skirt on the kayak you intend to use to ensure proper fit. Also of importance is how challenging it is to get the skirt attached to and released from the coaming.

You want the spray skirt to seal well enough to keep the water out but be easy to release with one hand. If the seal around the coaming is too tight, the skirt may not release easily during a wet exit; if it’s too loose, the paddler will have a cockpit full of water in no time, adversely affecting the kayak’s stability.

Another important aspect of a secure spray skirt pertains to the seal around the paddler’s waist, known as the tunnel. A number of factors can impact this seal, including the type of fabric, the type of closure or tightening system and, of course, the shape and size of the paddler.

In addition to testing the primary functions of these spray skirts, I wanted to see how well the various features performed, such as pockets, secondary release systems and other extras, and how well the features met the claims made by the manufacturers.

The spray skirts reviewed here were tested on both a fiberglass kayak and a plastic kayak.

Bomber GearTour de Jour

Bomber Gear’s Tour de Jour is made from a waterproof, breathable three-ply fabric. The spray deck is sewn to a rand (a sleeve of fabric sewn to the perimeter of the spray deck) made from a sticky rubber fabric.

Bomber Gear’s Tour de Jour is made from a waterproof, breathable three-ply fabric. The spray deck is sewn to a rand (a sleeve of fabric sewn to the perimeter of the spray deck) made from a sticky rubber fabric.

All seams except where the rand and spray deck meet are sewn and made waterproof with heat-sealed tape.

A length of elastic cord is routed through the sleeve and knotted at the back of the skirt. Although the elastic cord allowed the tension of the spray deck to be adjusted, the knot interfered with getting the skirt over both the fiberglass and plastic kayaks’ coaming.

It was only slightly difficult to attach it to the fiberglass coaming but notably difficult to get it started on the plastic coaming.

At the top of the tunnel, a three-inch-wide band of smooth neoprene is attached around the perimeter. This provides a sticky seal that is complemented by two hook-and-loop cinch tabs that pull forward to tighten the seal. The system worked well and stayed put once it was in place.

The Tour de Jour has a strip of plastic inserted in a fabric sleeve that is flexed by a strip under the deck into an arch to prevent water from pooling on the deck. The system worked very well—water quickly ran off the spray deck.

A band of reflective tape on the spray deck provides enhanced nighttime visibility. On the front of the tunnel, there is a zippered self-draining outer pocket. Inside, there is another pocket, just big enough for a small wallet, which has a roll-down dry-bag-type closure. I found the dry pocket to be too small to be convenient while afloat, but it does provide a place for ID, a bit of cash and car keys.

Brooks Wetsuits Zippered Neoprene Touring Spray Skirt

For those who don’t want to bother with wrestling the spray skirt on and off the coaming every time they want to reach inside the cockpit, Brooks Wetsuits offers the Zippered Neoprene Touring Spray Skirt.

Featuring a 3.5mm neoprene spray deck that is heavily reinforced with Duratex fabric over the entire deck, this skirt feels durable. The tunnel features stretch nylon inside and out that offers an extra layer of warmth.

The perimeter of the spray deck is folded over and sewn, creating a sleeve for an elastic cord. This seals around the kayak coaming and is adjustable via a knot in the back. Brooks has added a short plastic spacer that holds the knot away from the coaming edge so it doesn’t interfere with attaching the skirt at the back of the coaming.

The Zippered Touring Skirt could be stretched over a fiberglass coaming with moderate ease but with moderate difficulty on the more slippery plastic coaming. Once in place, the spray skirt was secure on both.

Two adjustable waist straps, one sewn onto each side of the skirt tunnel, ensure that the Zippered Neoprene Touring Spray Skirt stays secure and snug around the paddler’s waist. The system worked well and provided a good seal around my waist, but I found reaching back to the straps and buckles a bit awkward.

Though this skirt does not have any pockets, its zipper feature allowed easy access to the inside of the cockpit without removing the spray skirt from around the coaming.

A heavy-duty, waterproof zipper, the same kind as are used in dry suits, runs from the top of the tunnel down the front of the spray deck and stops a few inches short of the grab loop.

The zipper ends at the top of the tunnel, so unzipping the skirt usually requires opening a life jacket and lifting any apparel that may be covering the tunnel of the skirt. Although the zipper allowed easy access to the inside of my cockpit, I found that it was just as easy to pull the front of the spray skirt off if I wanted cockpit access.

Where the zipper did provide a significant benefit was getting in and out of the spray skirt.

A neoprene spray skirt with a snug tunnel can be a struggle to pull on over a wetsuit, especially for those with wider hips and a narrow waist. The zipper made it a breeze.

I just unzipped, pulled the skirt up around my waist and zipped it up. As with most dry suit zippers, this one needs to be kept clean and lubricated to operate smoothly (Brooks supplies a stick of zipper lubricant with the skirt). Without it, the zipper can get very stiff and difficult to use.

Kokatat Water Sportswear Offshore Deluxe Sea Skirt

Kokatat’s Offshore Deluxe Sea Skirt has a deck of 3mm neoprene, reinforced for durability with a rubber coating on the inside and on the outside along the forward edges of the coaming. Attached to the deck is a 4-oz. coated-nylon tunnel.

All seams, nylon and neoprene, are sealed on the inside. The seal around the coaming is secured with bungee cord externally stitched around the perimeter of the spray skirt.

Getting this spray skirt attached to a fiberglass coaming is moderately easy, requiring that you make sure the back of the skirt strap is anchored while you pull the spray deck forward. Getting it started on a plastic coaming was much more difficult because the back of the spray deck doesn’t have enough contour to hook around the plastic coaming and stay in place. Once fully attached on either coaming, the spray skirt had a secure fit yet released with relative ease.

The seal around the waist is achieved through a wide band of smooth-skin neoprene along the top edge of the nylon tunnel. Smooth-skin neoprene has an especially sticky characteristic that helps prevent the tunnel from slipping down.

The neoprene band is tightened around the torso by a pair of tabs with wide hook-and-loop patches. Cinching each tab back along the side of the skirt tunnel snugs the tunnel into place. Once I had it in place, the tunnel did not slip down around my waist, although tightening it would have been easier if the tabs were attached so that they pulled from back to front instead of front to back.

The tunnel is further supported by adjustable suspenders with stretch webbing. The suspenders are removable for wearing the spray skirt layered under paddle tops or dry suits with overskirts.

Kokatat has included a self-draining, zippered pocket at the front of the tunnel. The pocket is ample in size for a pair of gloves or a set of flares and a couple of energy bars. It has a zipper pull that was big enough for me to grasp while wearing gloves. Behind the cargo pocket is a fleece-lined hand-warming pouch.

Along the center of the spray deck, Kokatat has sewn a length of one-inch nylon webbing, which has two unsewn spans that provide places to clip gear, such as a GPS on a lanyard.

I found this feature quite useful, as I often like to secure gear right in front of me—not up on the foredeck of the kayak.

A second piece of webbing with strips of hook and loop sewn on it provides a way to secure a paddle or other gear quickly, if temporarily. Kokatat offers this spray skirt in the nylon/neoprene configuration reviewed here.

Mountain Surf Neo / Aqualogic Lindberdeck

The spray deck of the Mountain Surf spray skirt is made from durable 4mm neoprene laminated between two layers of nylon stretch fabric.

The deck is sewn and taped to a tunnel made of Aqualogic, a tough, breathable, waterproof fabric. The skirt looks both functional and durable.

At the edge of the spray deck, the rand is formed by a separate strip of neoprene attached around the perimeter of the spray deck. Inside the edge of neoprene is a strong O-ring of solid rubber, unlike the multi-filament bungee cords commonly used on other spray skirts, that provides the tension on the seal of the coaming.

Mountain Surf provides the O-rings in two different degrees of tension: E-Z fit or, for more extreme conditions, the Bomber Fit. The E-Z fit model tested was easy to attach and remove, and it fit and held exceptionally well around the coaming.

At the top of the tunnel, a two-inch-wide band of smooth neoprene is folded over and sewn around the top perimeter, creating a sleeve for the skirt’s quick-release chest belt. I found the system easy to use, and although it slipped down around my waist a little while paddling, it tended to stay in place.

A handy mesh pocket, large enough for a few pocket flares or energy bars, is attached to the front of the tunnel. Its zipper has a pull that can easily be grasped with wet or gloved hands.

Prijon / Wildwasser Pocket-System Neo/Neo

Prijon/Wildwasser offers the versatile Pocket-System Neo/Neo touring spray skirt. Simple in design, the forward edge of the spray deck is neoprene, faced with an abrasion- and UV-resistant Supratex weave designed to resist the wear caused by a paddle rubbing against the coaming.

The transition from the spray deck to the tunnel creates a tent-shaped sloping surface that sheds water easily. This is different from most spray skirts, where the nearly vertical tunnel is a tube sewn onto a flat spray deck.

An elastic cord is sewn to the outside perimeter of the spray deck, but it doesn’t curl the edge of the spray deck enough to hook around the cockpit coaming and anchor the back of the spray skirt while you stretch it forward. The comparatively flat perimeter of this spray deck made it somewhat difficult for me to attach it on the fiberglass coaming, and I needed help to install it on the plastic coaming.

Like some whitewater spray skirts, the Pocket-System Neo/Neo doesn’t have a belt of hook-and-loop tabs to adjust the fit around the paddler’s torso. Instead, the neoprene stretches to fit a girth from 30 to about 40 inches.

(Keep in mind that it gets tighter the farther it stretches.) For me, the stretch fit worked well on the water, creating a good seal around the waist and adding another layer for warmth.

The pocket feature of the Pocket-System Neo/Neo is a large mesh pocket sewn onto the forward portion of the spray deck. Unlike accessing a pocket sewn into the spray-skirt tunnel, which may require unzipping your life jacket, this pocket is easily accessible through a large zippered opening that faces toward the tunnel and is big enough to hold full-sized binoculars or a double-handful of miscellaneous items. This spray skirt is also available with a breathable fabric tunnel and suspenders for additional cost.

Snap Dragon Glacier Trek EZ

Snap Dragon introduced the Glacier Trek EZ as a new skirt for 2003. The spray deck on this skirt is a heavy-duty, 3.5mm, four-way-stretch neoprene. Attached to the deck is a tunnel made of breathable, waterproof Sympatex fabric, providing a cooler core area than a neoprene tunnel without the moisture-trapping properties of coated nylon.

Snap Dragon has perfected the shape of the seal around the coaming. On this spray skirt, the bungee is sewn to the edge of the spray deck. The neoprene deck is gathered as it is sewn, creating a slight curl that makes this skirt considerably easier to install over the coaming.

It was very easy to install over the fiberglass coaming but, like most spray skirts, was a bit slippery getting started on the coaming of the plastic kayak. Once in place, this spray skirt fit both cockpits exceptionally well.

Around the waist area of the skirt, the top of the Sympatex tunnel is rimmed with a four-inch band of neoprene. Hook-and-loop fabric tabs are used to cinch the tunnel around the waist of the paddler.

The tabs of hook fabric are at the side of the tunnel and pull forward to secure on the loop fabric sewn on the front of the tunnel. The system was simple to use, and it kept the skirt securely in place around my waist.

The Glacier Trek EZ lacks elaborate features, but it does have a great safety feature—the Knee-Off safety strap. A single length of flat webbing extends across the top of the spray deck and fastens to the rand at each side of the spray deck.

If the standard grab loop fails or gets inadvertently tucked under the forward edge of the spray skirt, pulling the Knee-Off safety strap releases the spray deck at the sides of the coaming. Its name, it should be pointed out, refers to its location above the knee, while the principal way of using it is to pull it by hand.

On some plastic kayaks, that may be enough to completely release the spray skirt. On the fiberglass kayak used for testing, the skirt did not come completely free of the coaming, but it pulled the edge of the skirt to the point where it was easy to grab and remove. The Knee-Off strap is an optional feature that adds about $8 to the retail price.

To seal themselves into the cockpits of their kayaks, the Native Greenland paddlers often use a tuiitsoq.

To seal themselves into the cockpits of their kayaks, the Native Greenland paddlers often use a tuiitsoq. The seams of the Brooks tuiliq are glued on the inside and sewn on the outside. Its hem has a rubber-side-out sleeve around a bungie cord that seals the tuiliq to the cockpit coaming.

The seams of the Brooks tuiliq are glued on the inside and sewn on the outside. Its hem has a rubber-side-out sleeve around a bungie cord that seals the tuiliq to the cockpit coaming.

The unit arrived without instructions; nevertheless, it took only a couple of minutes to figure out the sequence in pushing the two buttons to access current wind speed, maximum and average speeds, and to switch the display between miles per hour, kilometers per hour, meters per second, feet per minute and knots.

The unit arrived without instructions; nevertheless, it took only a couple of minutes to figure out the sequence in pushing the two buttons to access current wind speed, maximum and average speeds, and to switch the display between miles per hour, kilometers per hour, meters per second, feet per minute and knots.

is made from PVC-coated polyester in a simple, tapered shape, with no external pockets, save a mesh one at the rear big enough for sunscreen or a small water bottle. The bungies running across the top will secure (not very well) a chart in a ziplock.

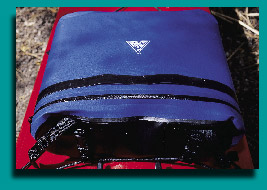

is made from PVC-coated polyester in a simple, tapered shape, with no external pockets, save a mesh one at the rear big enough for sunscreen or a small water bottle. The bungies running across the top will secure (not very well) a chart in a ziplock. The Aleutian is made from urethane-coated Cordura nylon, with welded seams. The bag is stiffened with a polyethylene sheet into a flattened ovoid shape that uses all of its modest 620 cubic inches efficiently. The zipper arcs over the top of the bag about three inches from the rear, so the back doesn’t fold down like a flap-you have to just push down on it to access the inside. Still, it works fine, and there’s a fabric flap that covers the zipper to help keep out grit. The bag is tall enough to hold my SLR camera (if I leave off the motor drive), and wide enough for a couple of extra lenses, plus a field guide and snacks-in other words, it has all the room you’re likely to need. Yet at only 12 1/2 inches wide (compared to 20 for the Watershed, including the clips), it’s compact enough to fit any deck.

The Aleutian is made from urethane-coated Cordura nylon, with welded seams. The bag is stiffened with a polyethylene sheet into a flattened ovoid shape that uses all of its modest 620 cubic inches efficiently. The zipper arcs over the top of the bag about three inches from the rear, so the back doesn’t fold down like a flap-you have to just push down on it to access the inside. Still, it works fine, and there’s a fabric flap that covers the zipper to help keep out grit. The bag is tall enough to hold my SLR camera (if I leave off the motor drive), and wide enough for a couple of extra lenses, plus a field guide and snacks-in other words, it has all the room you’re likely to need. Yet at only 12 1/2 inches wide (compared to 20 for the Watershed, including the clips), it’s compact enough to fit any deck. bottle, and still had room for my Gore-Tex shell when the morning turned warm. A stiffening sheet maintains the bag’s shape (and, as with most of these bags, is removable if you don’t want it).

bottle, and still had room for my Gore-Tex shell when the morning turned warm. A stiffening sheet maintains the bag’s shape (and, as with most of these bags, is removable if you don’t want it). Seattle Sports model, the inside of the Salamander bag stayed dry during what I’d call a fair-weather paddle-light breezes and small waves. I could have had a field guide inside with no worries. But when subjected to direct spraying or dunking the zipper leaked a small amount of water almost immediately, mostly through the small gap visible at the end of the zipper track.

Seattle Sports model, the inside of the Salamander bag stayed dry during what I’d call a fair-weather paddle-light breezes and small waves. I could have had a field guide inside with no worries. But when subjected to direct spraying or dunking the zipper leaked a small amount of water almost immediately, mostly through the small gap visible at the end of the zipper track.