Kayak Bill found his freedom under a regime of strict necessity, first on a wilderness of vertical rock, then in the wilds of a horizontal ocean. His goal was to be as independent of civilization as possible. By reversing civilization, he succeeded. For the last twenty-eight years of his life, Bill returned to a hunter-gatherer way of life. He must have spent more time than anyone in a sea kayak since aboriginal peoples left kayaks, as a way of life, behind. “Perfection consists in doing ordinary things extraordinarily well.”

-Bill Davidson

The first time I met Bill, it was 1968 and I was fifteen. He was working at the only store in Calgary (Western Canada) that then carried climbing gear. He sold me on buying the best hiking-climbing boots available. Bill’s enthusiasm and ready smile that day formed a memory that I’ve retained for 38 years.

Later, I found out that Bill Davidson was one of the hard-core climbers in the Calgary Mountain Club, part of a mountain climbing world to which I aspired. They were pushing climbing past the edge of the possible into what was only marginally sane. These were the kinds of guys who, had they not encountered mountains, would have excelled as Hell’s Angels. Many of them died with their climbing boots on.

The second time I crossed Bill’s path was my first day rock climbing. On a long rock face, my two high-school buddies and I picked the easiest route, a diagonal crack system. As we climbed through the crux, my nervousness abated as I realized that this was not that hard. Then we heard a shout. Puzzled, we looked over to a wall of blank limestone the size of a medium office tower. There was a person, although there was no ledge or crack big enough for a toenail. As we clambered nearer, we could see he was standing in two rope slings, leaning back away from the rock, smoking a cigarette. He yelled, “Hey, you guys. My backup bolt drill broke. I’m stuck. When you get down, see if you can get somebody to come up and lower a drill, from the top.” We did as he asked but nobody had anything useful to lower down.

The next morning Bill improvised his own gear repairs and rappelled down his climbing ropes. I had never conceived of the possibility of spending more than an afternoon on one of the steepest rock faces in the Canadian Rocky Mountains—that was Bill—nonchalant about spending a night hanging from his hand-drilled, hand-made bolts, 500 meters above the broad prairie.

Bill wrote an elaborately understated account of a climbing route on Mt. Gibraltar that he named, Nine Nightmarish Nights on Nothing, which never has been, and I expect never will be, repeated. As with many of his routes, he spent weeks going up and coming down until he wore a route up the rock. While solo aid climbing a section he took a 35-meter fall, gashing his head. He hitchhiked back to Calgary covered in blood. With his partner, Bill’s final ascent took nine continuous days on rock mostly beyond vertical. Then I heard a rumor about Bill taking a fifty meter fall on a solo climb—a fall that should have killed him. After that—nothing.

***

A dozen years later my mate Heather and I were paddling our double-seater sea kayak northeast of Vancouver Island toward the village of Echo Bay. The spring rain and sleet had briefly let up after a week of gloom. Through a hole in the clouds the sun was gleaming off the dark water when the biggest kayak that I had ever seen crossed our path. As the paddler approached, I saw that his kayak was a meter longer than our six-meter boat. On it were two large downriggers, one to each side of his front deck, for salmon fishing. We exchanged only a few words, as a wall of dark cloud was advancing, then we paddled off in opposite directions. Although I didn’t know it then, I had met Bill Davidson for the third time.

We asked the clerk at the Echo Bay general store about the kayaker, “Oh, that’s Kayak Bill. He has a camp at Eden Island, and a bunch of other camps around. He does a few odd jobs sometimes, but mostly he lives off the land. He started off from Vancouver about ten years ago to paddle to Alaska, but after wintering at Eden Island, he said he didn’t need to go any farther.”

Several years later, while camped on a tiny island near the Ivory Island lighthouse, we found a camp tucked away in the woods. The fireplace was unlike any other, three pieces of split wood of chest height had been driven into the ground forming a triangular column; two platforms of hand-split wooden slats were lashed together at navel and chest height. At the base several flat stones contained a bed of coarse sand and ashes. The fireplace was built for cooking at the bottom and for smoking food on the slats above.

The hollow of a cedar tree held two milk crates. The crates contained the tidiest firewood I’d ever seen; each piece was cut to precisely the same length and split to the exactly same diameter. The camp was situated so it would take minutes to string up ropes and throw up a tarp. Usually places where people make camps and fires are a mess—this was immaculate. Thumb-tacked to the fireplace was an empty package of Zig-Zag cigarette papers, the signature of Kayak Bill. Back home, I occasionally thought about Kayak Bill alone on an island somewhere out there. When I mentioned him to a long-time mountain guide, he told me, “Oh, that’s Billy Davidson; you must remember him from the Calgary Mountain Club.” He told me that Bill was raised in an orphanage and that he was a mechanical and electronic whiz kid; out of scrap metal and scrounged parts, for a provincial high school science fair he built a three-meter high robot that could pick up and crush a pop can. Bill took top prize but the orphanage could not afford to send him to the national competition. Years later, Bill soldered together a bunch of scavenged electronic parts into an early music synthesizer.

Over the years, Bill’s camps migrated northward as the more southerly kayaking spots got popular. Some of his camps were repeatedly trashed. He departed the Echo Bay area after the Forest Service tore down his Eden Island camp. One of his Goose Island camps was kicked apart more than once by native kids from Bella Bella. While chatting on a beach a fellow kayaker told me that he had met Bill at the south end of Aristizabel Island. Bill had told him that his main camp was somewhere in the vicinity.

On other kayak trips, I heard stories of Kayak Bill shooting deer and drying the meat. I was told he would rub himself with layers of rendered seal grease for sun and bug protection. He must have smelled ripe after cooking over open fires for months. There was a mention of a base camp out in Queen Charlotte Sound, near Goose Island, but in our two trips there Heather and I found only a couple of his temporary camps on some nearby islands.

In 1999, as we were returning from a two-week trip that had taken us near Aristizabel, we had camped on a pocket beach of clean sand facing the Pacific Ocean. After supper a kayaker paddled into view in a huge green and white kayak. He was using a homemade paddle double the length of our own longish paddles.

His complexion was so dark he no longer looked Caucasian. We squinted at his halo of frizzy hair backlit from the setting sun. Shielding her eyes, Heather asked, “You Kayak Bill?” “Yup,” he replied. He told us he was exhausted, as he had just paddled in one day what had taken us three days to cover. He gave us a warm invitation to visit his camp next morning—“It’s just around the corner, you’ll see my kayak on the beach”—and he was gone. When Heather and I woke the next day, impenetrable fog blanketed everything; we could not find his camp. That was the last time I saw him.

On a subsequent trip, I met Bill’s kayaking and artist friend Stewart Marshall camped on the shore of a rocky lagoon. He told me Bill had occasionally stayed on Malcolm Island off the northeast corner of Vancouver Island. For a period Bill had lived with a woman, they had a son they named Westerly after a fair wind, but Bill could not handle four walls permanently surrounding him. Bill came and went, but mostly he went.

I had long contemplated a kayak trip out toward Bill’s haunts in the hope of blundering across his path again. For me Bill embodied an ideal of self-sufficient competence. There was my curiosity about him, and there was something curious in how his path had repeatedly crossed mine in ways that were of consequence to me and inconsequential to him. But, there was no possibility of phoning or writing somebody who regularly spent ten months of the year alone on uninhabited islands. Even if I could have found where his camps were hidden, I doubt he would have revealed himself.

I needed to cross his path out on the ocean and to see his expression when I asked him about the robot. I wanted to know how he gathered clams and mussels and how he smoked his deer meat. I wanted to know how he could gauge the weather, waves, and currents so well that he never had an accident.

If he had ever misjudged the weather and flipped his loaded kayak, I doubt Bill could have righted it. It seems he never carried a lifejacket. In the places he paddled, there was nobody to rescue him, anyway. Even minor injuries, a slip on seaweed on a rocky beach dislocating his shoulder, or a single slip with an axe, or paralytic shellfish poisoning, could easily prove fatal. His safety lay in his solitary discipline. I knew from some of his friends on the coast that he often rehearsed his steps before carrying his kayak ashore and he always practiced packing and repacking his kayak before trips. All his trips were big, I never heard of him doing a moderate climb or less than a few months paddle. He needed an edge of danger to keep his skills and judgment honed.

The next I heard about Bill was a terse article in an American hiking magazine. I read that in March of 2003, near Goose Island, a deer hunter from Bella Bella had discovered Bill’s body at the edge of the sea, the cause of death undetermined.

Then in 2004, a poster appeared in Banff, where I live, featuring a smiling young Bill, climbing rope draped over one shoulder. There was to be a memorial service for Bill. I couldn’t attend. Some time later Heather discovered that her workmate, Perry, had been a buddy of Bill’s in high school. Perry told me more about Bill. They had done a ski-touring trip as teenagers. Bill did not have money for ski boots or for climbing skins for his wooden skis, so he adapted his homemade mukluks for boots and, he glued leather strips to his ski bases for skins. He glued the leather strips so they spelled out “far out, far out”— in the snow for 60 kilometers.

Perry showed me copies of Bill’s last journals and some of his charts. An idea came to me with a rush of goose bumps: I could not cross Bill’s path again, but I could parallel it by following his recorded camps out to the tiny group of islets out in Hecate Strait where he spent much of his last decade.

The route required five open-water crossings, each over 20 kilometers. I told myself that it shouldn’t be too risky, even though it looked exposed on the charts. After all, Bill paddled this route in much rougher winter weather. Bill recorded how he packed his kayak solid with 180 kilos of food and gear, sufficient for five months. He noted that he had just one centimeter of freeboard on his last trip to the islets; his kayak must have been closer to a submarine than a boat. I had a fancy, fast kayak with less than 35 kilos of food and gear. By moving faster than Bill I figured that I would be less exposed to the risks of changing weather.

I disembarked from the coastal ferry at the Kitasoo/Xai’xais village of Klemtu. The unusually strong flood current pushed me north. I had accidentally timed the turn of the tide perfectly so the ebb current then drew me west through narrow, rock-studded Meyers Passage. Elated at my fast progress, I went farther than I had intended, well past the few good camping spots.

I camped at the highest spot in a damp meadow squeezing my tent into the dense old cedar forest. Suddenly, I woke in the night, floating on my sleeping pad; I jumped naked out into darkness and ankle-deep water, telling myself the tide could not get any higher. For an hour, the water crept up almost to my knees, not until 3:30 AM did the tide fall enough to drain the tent. I was shivering as I groped my way into a sopping sleeping bag. In my rush to catch the ferry I had neglected to buy the tide tables that would have told me that that evening had the highest tide of the year.

I cursed myself until dawn for getting cocky. As I retrieved the wet gear that I had tossed into tree branches the night before, I found that the dry bag containing my extra charts, and my photocopies of Bill’s journals had drifted off. The supposedly waterproof case for my VHF radio had water inside—now I had no weather info and no Coast Guard rescue if I made a mistake. If I continued, I would be doing this trip too close to Bill’s style of travel, relying only upon myself. What I needed was to take more time, to sit until I had thought things through, like Kayak Bill.

After two days of drying gear out and watching the weather, I was out of bed just after 4:00 a.m., to cross Laredo Sound on a blue sky morning. The first breath of wind arrived just as I reached the ten kilometers of cliffs along the east side of the island. In minutes I located a Bill camp above a tiny beach in a break in the cliffs.

The camp was invisible from the water. Behind the bushes, a wall of driftwood three and a half meters high and six meters across protected the camp from prevailing winds. I continued southward into an archipelago dense with small rocky islands. Bill could safely paddle in here even in gale-force winds. He had situated his camps so he could sit out weeks of bad weather, waiting for the moment of calm, to make the exposed crossings.

After two and a half days of waiting at another of Bill’s camps, the winds unexpectedly calmed. I paddled off in the late afternoon into a slow two-meter swell. A few kilometers out from shore, a light breeze swept a thin layer of fog towards me. Missing the islets would mean a frightening, miserable night bobbing around in the Pacific Ocean, but I had an unusual confidence about continuing.

Soon I was enveloped by fog, but instead of diminishing the light, the thin fog diffused and amplified it—while the bow of my kayak stood out with an intense clarity—everything above and around was suffused by a directionless whiteness. The fog obliterated the islets, but a shimmering golden line from the setting sun still shone through, the slowly undulating reflections acted as a beacon guiding me straight onwards. In the distance I could hear several immense humid whale breaths, a pause, and then a few more breaths, no way to tell how far off. I stopped my steady paddling pace once, to hear distant swell breaking on rocks ahead. Using my ears as sonar I swiveled my head from side to side, I was on track.

Twenty minutes later, I arrived exactly where and when I needed to be after four hours on a bearing of 270 degrees. As the larger outer islands were mostly exposed rock and surf, I had to enter the islets exactly at that place to paddle through a protected channel into the middle islet. And I had to arrive at high tide, for at low or even medium tide, a reef of several square kilometers around the islets dries, blocking the access. I made a right turn into a channel flanked by dark rocks, where the water immediately calmed. As the sun set a few bonsai-shaped trees were starkly outlined by the golden fog. Two white fishing floats tied to separate trees marked something.

Why would Bill put up markers in a place he didn’t need to mark? Without those floats, I couldn’t have found a place flat enough for my tent. As I walked along an overgrown trail to Bill’s north camp, I had to veer around spiny Devil’s club bushes. In the last twilight, I threw a tarp up over the three beams, sat down on his raised bed of fitted planks, and tore into a plastic pouch of organic, free-range, smoked chicken.

The next morning, it took me five minutes to locate Bill’s south cabin. The north camp was a backup. A winter storm had once piled up waves high enough that Bill woke up in his cabin floating on his thin foam mattress, even though his bunk was two meters above high tide. Like his other camps, this was the size of a four meter by six meter plastic tarp. Unlike them, this place had a permanent roof with three and a half walls (the east wall was half open). Every piece of the cabin showed that it had been cast up by the sea.

The fireplace was like the others but more substantial, a double layer of thin, flat pieces of granite were closely fitted around the base with an empty pop can and coarse sand insulation in-between. Bill could have hot fires in here without burning the place down. There was an ingeniously arranged rack of moveable heavy bolts to hold pots. The bolts were from the boiler of a nearby shipwreck.

There were five cups, a dozen oddly shaped bottles along a shelf, a few eagle feathers, some plastic drums, three chests for storing food and a large perfectly intact sea-urchin shell. The only food was a small bag of chocolate pudding mix and three chocolate Santa Clauses—Bill had a sweet tooth. But there was no chimney. How could he live in the smoke? I made a small fire from his meticulously stacked firewood. The wall of driftwood just outside of the cabin faced the prevailing wind, creating a wind eddy, so the smoke was drawn up and then out under the roof line. Standing up I choked, but sitting on Bill’s bed, the smoke flowed out two feet above me. With a hot fire it would be warm in here even in winter. Outside the door, an open box three meters by three meters contained the remains from his staple diet, clam and muscle shells as big as my hands, heaped to chest height. This was no Hollywood castaway Tom Hanks; this was Robinson Crusoe for real and by choice.

Clearly, nobody had visited in the two and half years since Bill left. His Shearwater friends, Andrea and Bryan, had informed me that Bill’s health had lately deteriorated. A lifetime without dental care had left him with excruciating toothaches. His aching teeth and age (mid-fifties) had slowed him down, so he had not made it out here for a couple of seasons before his death.

No fresh water here, but I spotted another fishing float across the now dry channel. At low tide Bill’s islet connected with the two larger islands and to many small rocky islets. I found his well in the forest; he had punched the bottom out of a large plastic bucket and dug it into a damp spot in the forest floor. It must have taken him a couple of hours a day to gently dip out and haul water. He would have been busy what with, getting water, cooking, gathering food and fuel taking up most of his daylight hours. This place did have two advantages: Nobody would find this camp to wreck it. And, no flowing or standing water meant no mosquitoes or black flies. Bill hated bugs.

The next morning, I left under ideal sea conditions. Except for briefly paddling across the path of the coastal ferry, the six days back to Shearwater were pleasantly uneventful. In the Shearwater bar, I may have chewed the ears of four kayakers from Seattle, as I had not spoken for eighteen days.

Bill revealed something to me. Being alone out there—is not lonely. My loneliness disappeared as soon as I left people behind. Loneliness, it seems, appears in the presence of, rather than the absence of, people. Maybe Bill wasn’t seeking solitude as much as he was evading the loneliness he felt in civilized places. My loneliness arose in the last two hours paddling toward Shearwater to catch the ferry home. As I bobbed in the wakes from a procession of luxury yachts, I began to envy them. Besides being designed for water, yachts are also designed to inform those of us who cannot afford them, how deficient we are for not also having on-board microwave, satellite television, stocked bars, and hot showers.

The course of Bill’s life was opposite those too fast, too big, too white, and too expensive yachts. His path was to live with less, rather than impressing with more and more. Bill found an answer to his quest: What is the minimum that one man needs? He had no social insurance number, no health care, no credit card. His journals show that in the few months a year that he was in a village his budget was around two hundred dollars a month. I don’t know what kind of grubstake he needed to fill his boat with flour, sugar and a few Bic lighters, but it couldn’t have been more than several hundred dollars a couple of times a year. He became an artist, self-taught of course, partly to earn the little bit of money he needed.

Bill occupies a place in my imagination because he reversed the course of civilization. Except for Bill, civilization is a one-way trip. Once hunter-gatherers, be they in the Amazon or in the Arctic, enter a money economy and find out what life is like when they have pots, an axe, or a gun, a motor for their canoe, a snowmobile, or a permanent roof—they cannot go back. Once entered, civilization inexorably seduces us into the whole catastrophe: a job, a bank account, a mortgage, and then the yacht payments. Bill lived up to Henry David Thoreau’s phrase: “That man is richest whose pleasures are cheapest.”

In a material sense, Bill’s wake was as ephemeral as the wake from his kayak. However, I doubt that he realized the emotional wake he had left behind. Those who met him remarked on his smile and charisma, the opposite of the hermit image. He liked people even if he could not handle crowds and his idea of a crowd was three or more. I can understand going out into the wilderness for weeks, for months maybe, but for nine to ten months every year for twenty-eight years. What could possibly motivate anyone to that extreme?

From Bill’s friends, Perry Davis, Stewart Marshall and Andrea and Bryan Clerx, I gleaned a bit about Bill’s early life. When Bill was six, his mother disappeared. Bill’s father deposited his four children at a Calgary orphanage. From the age of six, onwards he had to be self-reliant. Bill’s younger sister was quickly adopted. Bill, his other sister, and his older brother lived in the orphanage until they finished high school. Bill’s father visited his children but they never had a family life. The separation and the orphanage must have branded into Bill an emotional pain and an equally deep resolve to become so self-disciplined and so perfectly self-sufficient that he inured himself to physical hardship and risk; to living on the vertical edge in his teens and twenties; to living at the edge of the ocean and beyond the edge of civilization for the rest of his life.

Bill began living off the land by running away from the orphanage. At its western edge, Calgary then had some forests where he could hide with food stolen from the orphanage, until hunger forced him back. As he got older he got better, staying away longer, learning to live from the land. Then, on a summer school outing he found a place that fit. On an easy scramble up the backside of the same rock face where he would later spend months on the vertical front side struggling against gravity, Bill later wrote in a published article, “When we got to the top, I was transfixed. The great height seemed to have me spellbound. Right from then, I knew I would be doing more climbing.” Through his iron discipline, he quickly developed mountain skills, which brought him into the frontier of rock climbing. In a few years he was doing the then hardest aid climbing routes on the planet. Through painstaking preparation Bill took on immense risks. He brought the same patient approach to his kayaking. Most of what happened to Kayak Bill out there will remain unknown. His terse journals recorded only what he needed to track, the weather, how much flour consumed, and how many lighters left. Bill made his last journal entries in December 2002. On the sixth he wrote, “Light rain showers. Lots of stew, plus sweet rice dish. Lower back and stomach pains.” For the morning of the seventh, he wrote, “Overcast with light rain showers and very light west wind. Fog and drizzle with winds light from the north and northwest by noon.” After that—blank pages.

But what I find most alluring about river travel is the idea of using the forces of nature to go somewhere. A river is like a conveyor belt. Get aboard it, and it will take you places hundreds, even thousands, of miles downstream. In 1994, I set my kayak in the headwaters of the Missouri River. Seventy-seven days later, it had carried me 2,500 miles to its confluence with the Mississippi. Looking back, I was terrifically unprepared. But time and necessity forced me to learn, and later to recognize problems before they occurred.

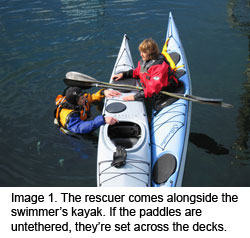

But what I find most alluring about river travel is the idea of using the forces of nature to go somewhere. A river is like a conveyor belt. Get aboard it, and it will take you places hundreds, even thousands, of miles downstream. In 1994, I set my kayak in the headwaters of the Missouri River. Seventy-seven days later, it had carried me 2,500 miles to its confluence with the Mississippi. Looking back, I was terrifically unprepared. But time and necessity forced me to learn, and later to recognize problems before they occurred. Preparation is the name of the game. Making sure everyone in the group knows what to do in the event of a capsize will significantly boost the group’s overall safety. Communication is crucial. Practice may not always make perfect or permanent, but it will help highlight the difficulties that “real” capsizes cause, and it will develop a system whereby a group has a better chance to rectify the situation.

Preparation is the name of the game. Making sure everyone in the group knows what to do in the event of a capsize will significantly boost the group’s overall safety. Communication is crucial. Practice may not always make perfect or permanent, but it will help highlight the difficulties that “real” capsizes cause, and it will develop a system whereby a group has a better chance to rectify the situation.